Colorado River – A Hardworking Waterway – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Colorado River.

The Colorado River is one of the principal rivers in the American Southwest and northern Mexico.

The Colorado River has carved out its place on Earth for over six million years. From its genesis on the Continental Divide in Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park, the river flows some 10,000 feet from the Rocky Mountains of Colorado to the Gulf of California, helping sustain a range of habitats and ecosystems as it weaves through mountains and deserts. Serving as a lifeline in the arid Western United States, the river nourishes the lives of 40 million people and endangered wildlife. Millions depend on the river for irrigation, water supply, and hydroelectric power. However, excessive water consumption and outdated management have endangered the Colorado River.

Initially known as the Grand, the river grows from a cold mountain trout stream into a classic Western waterway, slicing through jagged gorges between sweeping, pastoral ranchlands on the upper leg of a 1,450-mile journey.

From its headwaters in Colorado and Wyoming, the river and its tributaries pass through parts of seven states and serve Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming, along with 30 tribal nations. It is the fifth-longest river in the United States and winds through part of the Republic of Mexico before reaching the Gulf of California in wet years. Its stature continues to swell as it carves through some of the planet’s most iconic landscapes — desert canyons, buttes, and mesas — before being bottled up and sucked dry by agriculture and municipal demand. The name Colorado derives from Spanish for “colored reddish.”

Known for its dramatic canyons, whitewater rapids, and eleven U.S. National Parks, the Colorado River and its tributaries are a vital water source for 40 million people. An extensive system of dams, reservoirs, and aqueducts divert almost its entire flow for agricultural irrigation and urban water supply. Its large flow and steep gradient generate hydroelectricity, meeting peaking power demands in much of the Intermountain West. Intensive water consumption has dried up the lower 100 miles of the river, which has rarely reached the sea since the 1960s.

The Colorado River drainage area encompasses a wide range of natural environments—from Alpine tundra and coniferous forests in its headwaters and upper elevations through semiarid plateaus and canyons supporting pinon pine, juniper, and sagebrush to arid landscapes dotted with creosote bush and other desert plants in the lower basin and delta. The distribution of animals varies with these habitats. Large mammals such as the elk, mountain sheep, pronghorn, mule deer, mountain lion, bobcat, and coyote occupy the middle and upper elevations. Beavers, muskrats, and birds, including the bald eagle, favor stream banks lined with willow, cottonwood, and tamarisk.

Native Peoples

Paleo Indian People.

Native Americans have inhabited the Colorado River Basin for thousands of years. The first humans were likely Paleo-Indians of the Clovis and Folsom cultures, who first arrived on the Colorado River Plateau about 12,000 years ago. However, very little human activity occurred until the rise of the Desert Archaic Culture, which, from 8,000 to 2,000 years ago, constituted most of the region’s population. These prehistoric people led a nomadic lifestyle, gathering plants and hunting animals.

The Ancient Puebloans of the Four Corners region Desert Archaic culture first appeared around 1200 B.C. The Puebloans dominated the San Juan River Basin, with the center of their civilization in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. In the canyon and surrounding lands, they built more than 150 multi-story pueblos or “great houses,” the largest of which, Pueblo Bonito, comprises more than 600 rooms.

The Hohokam culture was present along the middle Gila River beginning around 1 A.D. Between 600 and 700 A.D., they began to employ irrigation on a large scale. They did so more prolifically than any other native group in the Colorado River Basin. An extensive system of irrigation canals was constructed on the Gila and Salt Rivers, with various estimates of a total length ranging from 180 to 300 miles and capable of irrigating 25,000 to 250,000 acres. Both civilizations supported large populations at their height; the Chaco Canyon Puebloans numbered between 6,000 and 15,000, and estimates for the Hohokam range between 30,000 and 200,000.

Colorado River Basin.

Beginning in the early centuries A.D., people in the Colorado River Basin began forming large agriculture-based societies, some of which lasted hundreds of years and grew into well-organized civilizations encompassing tens of thousands of inhabitants.

Another early group was the Fremont culture, which lived here from 2,000 to 700 years ago. They were likely the first people to domesticate crops and construct masonry dwellings. They also left behind a large amount of rock art and petroglyphs, many of which have survived to the present day.

The Navajo migrated from the north into the Colorado River Basin around 1,025 A.D. They soon established themselves as the dominant Native American tribe in the Colorado River Basin, and their territory stretched over parts of present-day Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado—the original homelands of the Puebloans. The Navajo acquired agricultural skills from the Puebloans before the collapse of the Pueblo civilization in the 14th century.

A profusion of other tribes has made a continued, lasting presence along the Colorado River. The Mohave have lived along the rich bottomlands of the lower Colorado River below Black Canyon since 1,200 A.D. They were fishermen — navigating the river on rafts made of reeds to catch Gila trout and Colorado pike minnow — and farmers, relying on the river’s annual floods rather than irrigation to water their crops. Ute people have inhabited the northern Colorado River Basin, mainly in present-day Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah, for at least 2,000 years but did not become well established in the Four Corners area until 1,500 A.D. The Apache, Cocopa, Halchidhoma, Havasupai, Hualapai, Maricopa, Pima, and Quechan are among many other groups with territories bordering the Colorado River and its tributaries.

These sedentary people heavily exploited their surroundings, practicing logging and harvesting other resources on a large scale. The construction of irrigation canals may have led to a significant change in the many waterways in the Colorado River Basin. Before human contact, rivers such as the Gila, Salt, and Chaco were shallow perennial streams with low, vegetated banks and extensive floodplains. In time, flash floods caused significant downcutting on irrigation canals, which led to the entrenchment of the original streams into arroyos, making agriculture difficult. Various methods were employed to combat these problems, including constructing large dams. However, when a megadrought hit the region in the 14th century A.D., the ancient civilizations of the Colorado River Basin abruptly collapsed. Some Puebloans migrated to the Rio Grande Valley of central New Mexico and south-central Colorado, becoming the predecessors of the Hopi, Zuni, Laguna, and Acoma people in western New Mexico. Many tribes that inhabited the Colorado River Basin during European contact were descended from Puebloan and Hohokam survivors. In contrast, others already had a long history of living in the region or migrated from bordering lands.

Early Exploration

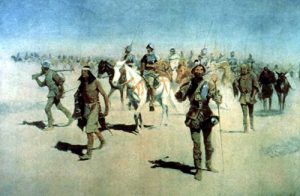

Coronado’s Expedition by Frederic Remington.

In the 1500s, Spanish explorers began mapping and claiming the watershed. An early motive was the search for the mythical Seven Cities of Gold, or “Cibola,” rumored to have been built by Native Americans somewhere in the desert Southwest. Francisco de Ulloa likely was the first European to see the Colorado River when, in 1536, he sailed to the head of the Gulf of California. Francisco Vasquez de Coronado’s 1540-1542 expedition began as a search for Cibola. Still, after learning from natives in New Mexico of a large river to the west, he sent García Lopez de Cardenas to lead a small contingent to find it. With the guidance of Hopi Indians, Cardenas and his men became the first outsiders to see the Grand Canyon. Cardenas was reportedly unimpressed with the canyon, assuming the width of the Colorado River was six feet and estimating 300-foot-tall rock formations to be the size of a man. After failing at an attempt to descend to the river, they left the area, defeated by the rugged terrain and torrid weather.

In 1540, Hernando de Alarcon and his fleet reached the mouth of the river, intending to provide additional supplies to Coronado’s expedition. Alarcon may have sailed the Colorado River as far upstream as the present-day California–Arizona border. Coronado never reached the Gulf of California, and Alarcon eventually gave up and left. Melchior Díaz reached the delta in the same year, intending to establish contact with Alarcon, but the latter was already gone by his arrival. He named the Colorado River Rio del Tizon, meaning “Firebrand River,” after seeing a practice used by the local natives for warming themselves. The name Tizon lasted for the next 200 years.

Navajo at Oasis, by Edward S. Curtis, 1904.

The Spanish introduced sheep and goats to the Navajo, who came to rely heavily on them for meat, milk, and wool. By the mid-16th century, the Ute, having acquired horses from the Spanish, introduced them to the Colorado River Basin. The use of horses spread through the basin via trade between the various tribes and greatly facilitated hunting, communications, travel, and warfare for indigenous peoples. The more aggressive tribes, such as the Ute and Navajo, often used horses to their advantage in raids against tribes that were slower to adopt them, such as the Goshute and Southern Paiute.

Beginning in the 17th century, contact with Europeans brought significant changes to the lifestyles of Native Americans in the Colorado River Basin. Missionaries sought to convert indigenous peoples to Christianity – an effort sometimes successful, such as in Father Eusebio Francisco Kino’s 1694 encounter with the “docile Pima of the Gila Valley who readily accepted him and his Christian teachings.” From 1694 to 1702, Kino explored the Gila and Colorado Rivers to determine if California was an island or peninsula. The name Rio Colorado, meaning “Red River,” was first applied to the Colorado River by Father Kino in his maps and written reports resulting from his explorations of the Colorado River Delta and his discovery that California was not an island but a peninsula in 1700-1702. Kino’s 1701 map, “Paso por Tierra a la California,” is the first known map to label the river as the Colorado River.

European and American Exploration

Jedediah Smith by Frederic Remington.

The gradual influx of European and American explorers, fortune seekers, and settlers into the region eventually led to conflicts that forced many Native Americans off their traditional lands. Mountain man Jedediah Smith reached the lower Colorado River through the Virgin River Canyon in 1826. Smith called the Colorado River the “Seedskeedee,” as the Green River in Wyoming was known to fur trappers, correctly believing it to be a continuation of the Green River and not a separate river as others believed under the Buenaventura myth. John C. Fremont’s 1843 Great Basin expedition proved that no river traversed the Great Basin and the Sierra Nevada.

Even after most of the watershed became U.S. territory in 1846, much of the river’s course remained unknown. Several expeditions charted the Colorado River in the mid-19th century—one of which, led by John Wesley Powell, was the first to run the rapids of the Grand Canyon.

After the acquisition of the Colorado River Basin from Mexico in the Mexican-American War in 1846, U.S. military forces commanded by Kit Carson forced more than 8,000 Navajo men, women, and children from their homes after a series of unsuccessful attempts to confine their territory, many of which were met with violent resistance. In what is now known as the Long Walk of the Navajo, the captives were marched from Arizona to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, and many died along the route. Four years later, the Navajo signed a treaty that moved them onto a reservation in the Four Corners region, now known as the Navajo Nation. It is the largest Native American reservation in the United States, encompassing 27,000 square miles with a population of more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members as of 2021.

Until the mid-19th century, long stretches of the Colorado River and Green rivers between Wyoming and Nevada remained largely unexplored due to their remote location and dangers of navigation. Because of the dramatic drop in elevation of the two rivers, there were rumors of huge waterfalls and violent rapids, and Native American tales strengthened their credibility.

Between 1850 and 1854, the U.S. Army explored the lower reach of the Colorado River from the Gulf of California, looking for the river to provide a less expensive route to supply the remote post of Fort Yuma. First, from November 1850 to January 1851, by its transport schooner, Invincible, under Captain Alfred H. Wilcox, and then by its longboat commanded by Lieutenant George Derby. Later, Lieutenant Derby, in his expedition report, recommended that a shallow draft sternwheel steamboat would be the way to send supplies upriver to the fort.

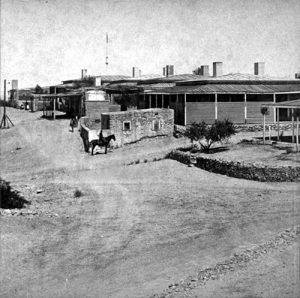

Fort Yuma, California.

Lorenzo Sitgreaves led the first Corps of Topographical Engineers mission across northern Arizona to the Colorado River near present-day Bullhead City and down its east bank to the Southern Immigrant Trail river crossings at Fort Yuma, California, in 1851.

The following contractors, George Alonzo Johnson and his partner Benjamin M. Hartshorne brought two barges and 250 tons of supplies arriving at the river’s mouth in February 1852 on the United States transport schooner Sierra Nevada under Captain Wilcox. Poling the barges up the Colorado River, the first barge sank with its cargo a total loss. After a long struggle, the second was finally poled up to Fort Yuma, but the garrison soon consumed what little it carried. Subsequently, wagons again were sent from the fort to haul the balance of the supplies overland from the estuary through the marshes and woodlands of the Delta.

At last, Lieutenant Derby’s recommendation was heeded, and in November 1852, the Uncle Sam, a 65-foot-long side-wheel paddle steamer, became the first steamboat on the Colorado River. Captain James Turnbull, in the schooner Capacity, brought it from San Francisco to the delta by the following contractor to provide supplies to the U.S. Army outpost at Fort Yuma, California. It was assembled and launched in an inlet 30 miles above the mouth of the Colorado River. Equipped with only a 20-horsepower engine, the Uncle Sam could only carry 35 tons of supplies, taking 15 days to make the first 120-mile trip. It made many trips up and down the river, taking four months to finish carrying the supplies for the fort, improving its time up river to 12 days. Negligence caused it to sink at its dock below Fort Yuma and was then washed away before it could be raised in the spring flood of 1853. Turnbull, in financial difficulty, disappeared. Nevertheless, he had shown the worth of steamboats to solve Fort Yuma’s supply problem.

The second Corps of Topographical Engineers expedition that crossed the Colorado River was the 1853-1854 Pacific Railroad Survey expedition along the 35th parallel north from Oklahoma to Los Angeles, California, led by Lieutenant Amiel Weeks Whipple.

Pacific Railroad Survey

George Alonzo Johnson, with his partner Hartshorne and a new partner, Captain Alfred H. Wilcox, formed George A. Johnson & Company and obtained the next contract to supply the fort. Johnson and his partners, all having learned lessons from their failed attempts ascending the Colorado River and with the example of the Uncle Sam, brought the parts of a more powerful side-wheel steamboat, the General Jesup, with them to the mouth of the Colorado River from San Francisco. There, it was reassembled at a landing in the upper tidewater of the river and reached Fort Yuma on January 18, 1854. This new boat, capable of carrying 50 tons of cargo, was very successful, making round trips to the fort in only four or five days. Costs were cut from 200to200 to 200to75 per ton.

Under Brigham Young’s grand vision for a “vast empire in the desert,” Mormon settlers were among the first whites to establish a permanent presence in the watershed, Fort Santa Clara, in the winter of 1855-1856 along the Santa Clara River, a tributary of the Virgin River.

Steamboats on the Colorado River at Fort Yuma, California.

George A. Johnson was instrumental in getting support for congressional funding for a military expedition up the river. With those funds, Johnson expected to provide transportation for the expedition. However, he was angry and disappointed when the expedition commander, Lieutenant Joseph Christmas Ives, rejected his offer of one of his steamboats. Before Ives could finish reassembling his steamer in the delta, George A. Johnson set off from Fort Yuma on December 31, 1857, exploring the river above the fort in his steamboat, General Jesup. He ascended the river in 21 days as far as the first rapids in Pyramid Canyon, over 300 miles above Fort Yuma and eight miles above the modern site of Davis Dam. Running low on food, he turned back. As he returned, he encountered Lieutenant Ives, Whipple’s assistant, who was leading an expedition to explore the feasibility of using the Colorado River as a navigation route in the Southwest. Ives and his men used a specially built steamboat, the shallow-draft U.S.S. Explorer, and traveled up the river as far as Black Canyon. He then took a small boat up beyond the canyon to Fortification Rock and Las Vegas Wash. After experiencing numerous groundings and accidents and having been inhibited by low water in the river, Ives declared: “Ours has been the first, and will doubtless be the last, party of whites to visit this profitless locality. It seems intended by nature that the Colorado River, along the greater portion of its lonely and majestic way, shall be forever unvisited and undisturbed.”

Steamboats quickly became the principal source of communication and trade along the river until railroad competition began in the 1870s.

The Mohave were expelled from their territory after a series of minor skirmishes and raids on wagon trains passing through the area in the late 1850s, culminating in an 1859 battle with American forces that concluded the Mohave War. In 1870, the Mohave were relocated to a reservation at Fort Mojave, which spans the borders of Arizona, California, and Nevada. Some Mohave were also moved to the 432-square-mile Colorado River Indian Reservation on the Arizona-California border, initially established for the Mohave and Chemehuevi people in 1865. In the 1940s, some Hopi and Navajo people were relocated to this reservation. The four tribes now form a geopolitical body known as the Colorado River Indian Tribes.

Mining was the primary spur of economic development in the lower Colorado River region. Copper mining began in southwestern New Mexico Territory in the 1850s. In 1859, a group of adventurers from Georgia discovered gold along the Blue River in Colorado and established the mining boomtown of Breckenridge. This was followed by the Mohave War and a gold rush on the Gila River in 1859, the El Dorado Canyon Rush in 1860, and the Colorado River Gold Rush in 1862.

In 1860, anticipating the Civil War, Mormons established several settlements to grow cotton along the Virgin River in Washington County, Utah. Soon, gold and silver strikes drew prospectors to the upper Colorado River Basin.

Eldorado Canyon, Nevada by Amy Stark.

From 1863 to 1865, Mormon colonists founded St. Thomas and other colonies on the Muddy and Virgin Rivers in present-day Clark County, Nevada. In 1866, these colonists on the Colorado River established Stone’s Ferry at the mouth of the Virgin River to carry their produce on a wagon road to the mining districts of Mohave County, Arizona. The same year, a steamboat landing was established at Callville, Nevada, intended as an outlet to the Pacific Ocean via the Colorado River. The area settlements reached a peak population of about 600 before being abandoned in 1871, and for nearly a decade, these valleys became a haven for outlaws and cattle rustlers. One Mormon settler, Daniel Bonelli, remained, operating the ferry and mining salt in nearby mines, bringing it in barges downriver to El Dorado Canyon, where it was used to process silver ore.

One of the main reasons the Mormons were able to colonize Arizona was the existence of Jacob Hamblin’s ferry across the Colorado River at present-day Lee’s Ferry, then known as Pahreah Crossing, which began running in March 1864. This location was the only section of river for hundreds of miles in both directions where the canyon walls dropped away, allowing for the development of a transport route.

Until 1866, El Dorado Canyon was the head of navigation on the Colorado River. That year, Captain Robert T. Rogers, commanding the steamer Esmeralda with a barge and 90 tons of freight, reached Callville, Nevada, on October 8, 1866.

The first federally funded irrigation project in the U.S. was the construction of an irrigation canal on the Colorado River Indian Reservation in 1867.

In 1869, one-armed Civil War veteran John Wesley Powell led an expedition from Green River Station in Wyoming, aiming to run the two rivers down to St. Thomas, Nevada, near present-day Hoover Dam. Powell and nine men, none of whom had prior whitewater experience, set out in May. After braving the rapids of the Gates of Lodore, Cataract Canyon, and other gorges along the Colorado River, the party arrived at the mouth of the Little Colorado River.

We are three-quarters of a mile in the depths of the earth, and the great river shrinks into insignificance as it dashes its angry waves against the walls and cliffs that rise to the world above; they are but puny ripples, and we but pigmies, running up and down the sands, or lost among the boulders. We have an unknown distance yet to run, an unknown river yet to explore. What falls there are, we know not; what rocks beset the channel, we know not; what walls rise over the river, we know not. Ah, well! We may conjecture many things. The men talk as cheerfully as ever; jests are bandied about freely this morning, but to me, the cheer is somber, and the jests are ghastly.

— John Wesley Powell’s journal, August 1869

John Doyle Lee established a more permanent ferry system at the site in 1870. One reason Lee chose to run the ferry was to flee from Mormon leaders who held him responsible for the Mountain Meadows Massacre, in which 120 emigrants in a wagon train were killed by a local militia disguised as Native Americans. Even though it was located along a major travel route, Lee’s Ferry was very isolated, and there, Lee and his family established the aptly named Lonely Dell Ranch.

Hohokam People.

Mormons founded settlements along the Duchesne River Valley in the 1870s and populated the Little Colorado River valley later in the century, settling in towns such as St. Johns, Arizona. They also established settlements along the Gila River in central Arizona in 1871. These early settlers were impressed by the extensive ruins of the Hohokam civilization that previously occupied the Gila River Valley. They are said to have “envisioned their new agricultural civilization rising as the mythical phoenix bird from the ashes of Hohokam society.” The Mormons were the first whites to develop the basin’s water resources on a large scale. They built complex networks of dams and canals to irrigate wheat, oats, and barley and establish extensive sheep and cattle ranches.

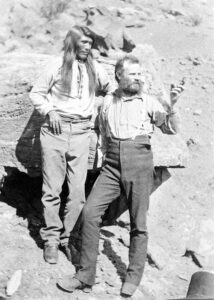

John Wesley Powell with Paiute Indian.

John Wesley Powell led a second expedition in 1871 with financial backing from the U.S. government. The explorers named many features along the Colorado River and Green Rivers, including Glen Canyon, the Dirty Devil River, Flaming Gorge, and the Gates of Lodore. Modern-day Lake Powell, which floods Glen Canyon, is also named for their leader.

In 1875, even more significant gold strikes were made along the Uncompahgre and San Miguel Rivers in Colorado, which led to the creation of Ouray and Telluride. Because most gold deposits along the upper Colorado River and its tributaries occur in lode deposits, extensive mining systems and heavy machinery were required to extract them.

Callville, Nevada, remained the head of navigation on the river until July 7, 1879, when Captain J. A. Mellon in the Gila left El Dorado Canyon landing, steamed up through the rapids in Black Canyon, making record time to Callville and tied up overnight. The following day, he steamed up through the rapids in Boulder Canyon to reach the mouth of the Virgin River at Rioville on July 8, 1879. From 1879 to 1887, Rioville, Nevada, was the highwater Head of Navigation for the steamboats and the mining company sloop Sou’Wester that carried the salt needed for the reduction of silver ore from there to the mills at El Dorado Canyon.

From 1879 to 1887, Colorado Steam Navigation Company steamboats carried the salt, operating upriver in the high spring flood waters, through Boulder Canyon to the landing at Rioville at the mouth of the Virgin River. From 1879 to 1882, the Southwestern Mining Company, largest in El Dorado Canyon, brought in a 56-foot sloop, the Sou’Wester, that sailed up and down river carrying the salt in the low water time of year until it was wrecked in the Quick and Dirty Rapids of Black Canyon.

The Grand Ditch near Rocky Mountain National Park by Carol Highsmith, 2015.

Large-scale development of Colorado River water supplies started in the late 19th century at the river’s headwaters in La Poudre Pass. The Grand Ditch, one of the earliest water diversions of the Colorado River, directing runoff from the river’s headwaters across the Continental Divide to arid eastern Colorado, was considered an engineering marvel when completed in 1890. The Grand Ditch is still in use today. It was the first of 24 “transmountain diversions” constructed to draw water across the Rocky Mountains as the Front Range corridor increased in population. These diversions draw water from the upper Colorado River and its tributaries into the South Platte River, Arkansas River, and Rio Grande basins.

At about the same time, the Colorado River region in Mexico became a favored place for Americans to invest in agriculture when Mexican President Porfirio Díaz welcomed foreign capital to develop the country. The Colorado River Land Company, formed by Los Angeles Times publisher Harry Chandler, his father-in-law Harrison Gray Otis, and others, developed the Mexicali Valley in Baja California as a thriving land company. The company headquarters was nominally based in Mexico, but its actual headquarters was in Los Angeles, California. Land was leased mainly to Americans who were required to develop it. Colorado River was used to irrigate the rich soil. The company largely escaped the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution between 1910 and 1920. Still, in the postrevolutionary period, the Mexican government expropriated the company’s land to satisfy the demand for land reform.

In 1900, the California Development Company envisioned irrigating the Imperial Valley, a then-dry basin on the California-Mexico border, using water from the Colorado River. Due to the valley’s location below sea level, water could be diverted and allowed to flow there entirely by gravity. Engineer George Chaffey was hired to design the Alamo Canal, which split from the Colorado River near Pilot Knob, California, and ran south into Mexico, where it joined the Alamo River, a dry arroyo that had historically carried overflowing floodwaters from the Colorado River into the Salton Sink at the bottom of Imperial Valley. The scheme worked initially; by 1903, about 4,000 people lived in the valley, and more than 100,000 acres of farmland had been developed.

Salton Sea, California by Kathy Alexander.

In early 1905, flooding destroyed the intake gates, and water began to flow uncontrolled down the canal toward the Salton Sink. By August, the breach had grown large enough to swallow the entire flow of the river, which began to flood the bottom of the valley. The Southern Pacific Railroad attempted to dam the flow to protect their tracks, which ran through the valley but were hampered by repeated flooding. It took seven attempts, more than $3,000,000, and two years for the railroad, the California Development Company, and the federal government to permanently block the breach and restore the river’s original course — but not before part of the Imperial Valley was flooded under a 45-mile-long lake, today’s Salton Sea. The Imperial Valley fiasco demonstrated that further economic development of the region would require a dam to control the Colorado River’s unpredictable flows.

The Colorado River’s signature attraction—the awe-inspiring Grand Canyon—wasn’t recognized as a national monument by President Theodore Roosevelt until 1908 and as a national park 11 years later.

Large-scale river management began in the early 1900s, with major guidelines established in a series of international and U.S. interstate treaties known as the “Law of the River.” In 1909, dams along the lower river were constructed, with no locks to allow ships to pass through. The U.S. federal government constructed most major dams and aqueducts between 1910 and 1970. During the extensive water resources development carried out on the river and its tributaries in the 19th and 20th centuries, the water rights of Native Americans in the Colorado River Basin were largely ignored.

In 1922, a 15-foot high wave swamped a ship bound for Yuma, Arizona, killing between 86 and 130 people.

Lees Ferry at Glen Canyon on the Colorado River by the National Park Service.

That year, six U.S. states signed the Colorado River Compact, which divided half of the river’s flow to both the Upper Basin (the drainage area above Lee’s Ferry, comprising parts of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming and a small portion of Arizona) and the Lower Basin (Arizona, California, Nevada, and parts of New Mexico and Utah). The Upper and Lower Basin were each allocated 7.5 million acre-feet of water per year, a figure believed to represent half of the river’s annual flow at Lee’s Ferry. The allotments operated under the premise that approximately 17.5 million acre-feet of water flowed through the river annually.

Arizona initially refused to ratify the compact because it feared that California would take too much of the lower basin allotment. In 1944, a compromise was reached in which Arizona was allocated 2.8 million acre-feet, but with the caveat that California’s 4.4-million-acre-foot allocation was prioritized during drought years. These and nine other decisions, compacts, federal acts, and agreements made between 1922 and 1973 constitute what is now known as the Law of the River.

Navajo Bridge Spanning the Colorado River, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Arizona by Brian Grogan, 1993.

In 1928, the Lee’s Ferry sank, resulting in the deaths of three men. Later that year, the Navajo Bridge was completed at a point five miles downstream, rendering the ferry obsolete.

Construction on the Colorado River-Big Thompson Project began in the 1930s. Today, it is the largest of the transmountain diversions, delivering 230,000 acre-feet per year from the Colorado River to cities north of Denver, Colorado. Numerous other projects followed, including the Roberts Tunnel, which delivers water from the Blue River to Denver, and the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, which diverts water from the Fryingpan River to the Arkansas River basin.

A large dam on the Colorado River had been envisioned since the 1920s. The Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928 authorized the construction of a dam along the river and the All-American Canal to connect the river to the Imperial and Coachella Valleys. It also divided the water among the Lower Basin states. Its key feature would be a dam on the Colorado River in Black Canyon, 30 miles southeast of Las Vegas, Nevada. On September 30, 1935, Hoover Dam was completed, forming Lake Mead, capable of holding more than two years of the Colorado River’s flow. Lake Mead was, and still is, the largest artificial lake in the U.S. by storage capacity. The Hoover Dam construction stabilized the Colorado River’s lower channel, stored water for irrigation during drought, captured sediment, and controlled floods. Hoover was the tallest dam in the world at the time of construction and also had the world’s largest hydroelectric power plant.

Hoover Dam, NV, by Carol Highsmith, 2018.

The Boulder Canyon Project Act also authorized the All-American Canal, which was built as a permanent replacement for the Alamo Canal and followed a route entirely within the United States on its way to the Imperial Valley. The canal’s intake is located at Imperial Dam, 20 miles above Yuma, Arizona, which diverts most of the Colorado River’s flow, with only a small portion continuing to Mexico. With a capacity of over 26,000 cubic feet per second, the All-American Canal is the largest irrigation canal in the world. Because the hot, sunny climate lends to a year-round growing season, the Imperial Valley has become one of North America’s most productive farming regions, providing much of the winter produce supply in the U.S. The Imperial Irrigation District supplies water to 520,000 acres south of the Salton Sea. The Coachella Canal, which branches northward from the All-American Canal, irrigates another 78,000 acres in the Coachella Valley. Congress officially designated the dam as Hoover Dam in 1947.

Parker Dam was initially built as the diversion point for the Colorado River Aqueduct, which the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California planned to supply water to Los Angeles. Arizona opposed the dam’s construction, which feared that California would take too much water from the Colorado River; at one point, Arizona sent members of its National Guard to stop working on the dam. Ultimately, a compromise was reached, with Arizona dropping its objections in exchange for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation constructing the Gila Project, which irrigates 110,000 acres on the Arizona side of the river. The construction of dams has often had negative impacts on tribal peoples, such as the Chemehuevi, when their riverside lands were flooded after the completion of Parker Dam in 1938.

By 1941, the 241-mile-long Colorado River Aqueduct was completed, delivering 1.2 million acre-feet of water west to Southern California. The aqueduct enabled the continued growth of Los Angeles and its suburbs and provides water to about 10,000,000 people today. The San Diego Aqueduct, which branches off from the Colorado River Aqueduct in Riverside County, California, opened in stages between 1954 and 1971 and provided water to another 3,000,000 people in the San Diego metro area.

Boulder Beach at Lake Mead, Nevada, by Dave Alexander.

The Las Vegas Valley of Nevada experienced rapid growth after Hoover Dam was built, and by 1937, Las Vegas had tapped a pipeline into Lake Mead. Nevada officials, believing that groundwater resources in the southern part of the state were sufficient for future growth, were more concerned with securing a large amount of the dam’s power supply than water from the Colorado River; thus, they settled for the smallest water allocation of all the states in the Colorado River Compact In 2018, due to declining water levels in Lake Mead, a second pipeline was completed with a lower intake elevation.

In 1944, a treaty between the U.S. and Mexico allocated 1.5 million acre-feet of Colorado River water to Mexico each year.

In 1948, the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact created the Upper Colorado River Commission and apportioned the Upper Basin’s 7.5 million acre-feet among Colorado (51.75%), New Mexico (11.25%), Utah (23%), and Wyoming (14%). The International Boundary and Water Commission regulates the allocation of water from the Colorado River to Mexico and also apportions waters from the Rio Grande between the two countries.

In the first half of the 20th century, the Upper Basin states, except for Colorado, had developed very little of their water allocations from the Colorado River Compact. Morelos Dam was constructed in 1950 to enable Mexico to utilize its share of the river.

By the 1950s, however, water demand was rapidly increasing in Utah’s Salt Lake City metro area and the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico, which both began exploring ways to divert water from the Colorado River Basin. The Upper Basin states were concerned that they could not use their full Compact allocations due to increasing water demands in the Lower Basin. The Compact requires the Upper Basin to deliver a minimum annual flow of 7.5 million acre-feet past Lee’s Ferry (measured on a 10-year rolling average). Without additional reservoir storage, the Upper Basin states could not utilize their allocations without impacting water deliveries to the Lower Basin in dry years.

In 1956, Congress authorized the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to construct the Colorado River Storage Project, which planned several large reservoirs on the upper Colorado, Green, Gunnison, and San Juan Rivers. The Act authorized the construction of the Wayne N. Aspinall Unit in Colorado, the Flaming Gorge Unit in Utah, the Navajo Unit in New Mexico, and the Glen Canyon Unit in Arizona. This move was criticized by both the National Park Service and environmental groups. The controversy received nationwide media attention, and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation dropped its plans for the large dams in exchange for increasing the size of a proposed dam at Glen Canyon.

Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Arizona, by Dave Alexander.

The controversy associated with Glen Canyon Dam did not build momentum until construction was well underway. Due to Glen Canyon’s remote location, most Americans did not even know of its existence; the few who did contend that it had much greater scenic value than Echo Park. The environmental movement in the American Southwest has opposed the damming and diversion of the Colorado River system due to negative effects on the ecology and natural beauty of the river and its tributaries. During the construction of Glen Canyon Dam from 1956 to 1966, environmental organizations vowed to block any further river development, and some later dam and aqueduct proposals were defeated by citizen opposition.

In addition to Glen Canyon Dam, the Colorado River Storage Project includes the Flaming Gorge Dam on the Green River, the Blue Mesa, Morrow Point, and Crystal Dams on the Gunnison River, and the Navajo Dam on the San Juan River. Later, 22 “participating projects” were luthorized to develop local water supplies at various locations across the Upper Basin states. These include the Central Utah Project, which delivers 102,000 acre-feet per year from the Green River basin to the Wasatch Front, and the San Juan-Chama Project, which diverts 110,000 acre-feet per year from the San Juan River to the Rio Grande Valley. Both are multi-purpose projects serving a variety of agricultural, municipal, and industrial uses.

By the middle of the 20th century, planners were concerned that continued growth in water demand would outstrip the available water supply from the Colorado River. Due to water diversions, flows at the mouth of the river have steadily declined since the early 1900s. Since 1960, the Colorado River has typically dried up before reaching the sea, except for a few wet years. In addition to water consumption, flows have declined due to reservoir evaporation and warming temperatures that reduce winter snow accumulation.

After exploring many potential projects, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation published a study in January 1964 called the Pacific Southwest Water Plan, which proposed diverting water from the northwestern United States into the Colorado River Basin. Arizona’s water allocation was a significant focus of the plan due to the growing concern that its water supply could be curtailed due to California’s seniority of water rights. In addition, the plan would guarantee full water supplies to Nevada, California, and Mexico, allowing the Upper Basin states to utilize their total allocations without risking reductions in the Lower Basin. The project would cost an estimated $3.1 billion.

Roosevelt Dam by Dave Alexander.

In 1968, the Colorado River Basin Project Act authorized the Central Arizona Project. The first stage of this plan would divert water from Northern California’s Trinity, Klamath, and Eel Rivers to Southern California, allowing more Colorado River water to be used by exchange in Arizona. A canal system would be constructed to deliver Arizona’s Colorado River allocation to Phoenix and Tucson, located far away from the Colorado River in the middle of the state. Central Arizona was still entirely dependent on local water supplies, such as the 1911 Theodore Roosevelt Dam, and quickly ran out of surplus water.

To supply the massive amount of power required to pump Colorado River water to central Arizona, two hydroelectric dams were proposed in the Grand Canyon (Bridge Canyon Dam and Marble Canyon Dam), which, while not directly located in Grand Canyon National Park, would significantly impact flows of the Colorado River through the park. With the ongoing controversy over Glen Canyon Dam, the public pressure against these dams was immense. As a result, the two Grand Canyon dams were omitted from the final Central Arizona Project authorization in 1968. In addition, the boundaries of Grand Canyon National Park were redrawn to prevent future dam projects in the area. The coal-fired Navajo Generating Station near Page, Arizona, replaced the pumping power in 1976. In 2019, the Navajo Generating Station ceased operation.

The Central Arizona Project was constructed in stages from 1973 to 1993, ultimately extending 336 miles from the Colorado River at Parker Dam to Tucson, Arizona. It delivers 1.4 million acre-feet of water annually, irrigates 830,000 acres of farmland, and provides about five million people with municipal water. Due to environmental concerns, most of the facilities proposed in the Pacific Southwest Water Plan were never built, leaving Arizona and Nevada vulnerable to future water reductions under the Compact.

The most severe drought, the southwestern North American megadrought, began in the early 21st century. The river basin produced above-average runoff in only five years between 2000 and 2021. The region is experiencing a warming trend accompanied by earlier snowmelt, lower precipitation, and greater evapotranspiration. A 2004 study showed that a 1-6% decrease in precipitation would lead to runoff declining by as much as 18% by 2050.

Lake Powell, Arizona, by Kathy Alexander.

Since 2000, reservoir levels have fluctuated dramatically from year to year but have experienced a steady long-term decline. The dry spell between 2000 and 2004 brought Lake Powell to just a third of capacity in 2005, the lowest level on record since initial filling in 1969. In late 2010, Lake Mead was approaching the “drought trigger” elevation of 1,075 feet, at which the Colorado River Compact would reduce water supplies to Arizona and Nevada. Due to Arizona and Nevada’s water rights being junior to California’s, their allocations can legally be cut to zero before any reductions are made on the California side.

A wet winter in 2011 temporarily raised lake levels, but dry conditions returned in the next two years. In 2014, the Bureau of Reclamation cut releases from Lake Powell by 10%—the first such reduction since the 1960s, when Lake Powell was being filled for the first time. This resulted in Lake Mead dropping to its lowest recorded level since 1937 when it was first filled.

In 2012, the U.S. and Mexico signed Minute 319, establishing new rules for sharing Colorado River water through a five-year pact. With limited storage capacity, Mexico could store some of its Colorado River water in Lake Mead. In exchange, should a shortage be declared in the Lower Basin, less water would be sent to Mexico.

The idea of a Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan emerged in 2013 as an overlay to the 2007 shortage-sharing agreement. After the intense drought of the early 2000s, stakeholders breathed a sigh of relief with a high river flow in 2011, followed by the lowest consecutive years on record. Suddenly, the possibility of Lake Mead dropping to a dead pool (when the water level is so low that it cannot drain by gravity through Hoover Dam’s outlets) didn’t seem far-fetched.

Ten Native American tribes in the basin now hold or continue to claim water rights to the Colorado River. The U.S. government has taken some actions to help quantify and develop the water resources of Native American reservations. Other water projects include the Navajo Indian Irrigation Project, which was authorized in 1962 to irrigate lands in part of the Navajo Nation in north-central New Mexico. The Navajo continue to seek expansion of their water rights because of difficulties with the water supply on their reservation; about 40% of its inhabitants must haul water by truck many miles to their homes. In the 21st century, they have filed legal claims against Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah governments for increased water rights. Some of these claims have been successful for the Navajo, such as a 2004 settlement in which they received a 326,000-acre-foot allotment from New Mexico.

In 2018, the Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes Partnership Tribal Water Study was released. That study described how tribes use their water, how future water development could occur, and the potential effects of future tribal water development on the Colorado River system. The study identified challenges related to the use of tribal water and explored opportunities that provide a wide range of benefits to both Partnership Tribes and other water users.

Dry Echo Bay at Lake Mead, Nevada, by Kathy Alexander.

The water year 2018 had a much lower-than-average snowpack. After six years of negotiations, the Drought Contingency Plan was signed into law in 2019. The Upper Basin portion of the plan protects elevations at Lake Powell and authorizes storage of conserved water in the Upper Basin. The Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan requires Arizona, California, and Nevada to contribute additional water to Lake Mead storage. It creates additional flexibility to incentivize voluntary conservation of water to be stored in Lake Mead.

In July 2021, after two more arid winters, Lake Powell fell below the previous low set in 2005. In response, the Bureau of Reclamation began releasing water from upstream reservoirs to keep Powell above the minimum level for hydropower generation. Lake Mead fell below the 1,075-foot level expected to trigger federally mandated cuts to Arizona and Nevada’s water supplies for the first time in history and is expected to continue declining into 2022.

On August 16, 2021, the Bureau of Reclamation released the Colorado River Basin August 2021 24-Month Study, and for the first time, declared a shortage and that because of “ongoing historic drought and low runoff conditions in the Colorado River Basin, downstream releases from Glen Canyon Dam and Hoover Dam will be reduced in 2022 due to declining reservoir levels.” The Lower Basin reductions will reduce the annual apportionments – Arizona’s by 18%, Nevada’s by 7%, and Mexico’s by 5%.

On June 14, 2022, Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton told the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources that additional 2-4 million acre-feet cuts were required to stabilize reservoir levels in 2023. Touton warned that the Interior Department may use its legal authority to cut releases if states could not negotiate the requisite cuts. When the states could not agree on how to share the proposed cuts, Reclamation began the legal steps to unilaterally reduce releases from Hoover and Glen Canyon Dams in 2023. As of December 2022, the lower basin states of Nevada, Arizona, and California had not agreed on reducing water use by the approximately 30% required to keep levels in lakes Mead and Powell from crashing. The Bureau of Reclamation has projected that water levels at Lake Powell could fall low enough that by July 2023, Glen Canyon Dam would no longer be able to generate any hydropower. Arizona proposed a plan that severely cut allocations to California, and California responded with a plan that severely cut allocations to Arizona, failing to reach a consensus. In April 2023, the federal government proposed evenly cutting allocations to Nevada, Arizona, and California, cutting deliveries by as much as one-quarter to each state rather than according to senior water rights.

Dry Lake Mead by John Locher, Associated Press, 2022.

In May 2023, the states finally reached a temporary agreement to prevent a dead pool, reducing allocations by three million acre-feet over three years (until the end of 2026). California, Arizona, and Nevada would negotiate 700,000 acre-feet later. The cuts were less than the federal government had demanded, so further cuts would be needed after 2026. Fewer cuts were needed in the short term because the Colorado River Basin experienced stormy and snowy weather in early 2023.

The agreement also became easier to negotiate because one-time federal funding offset many cuts. Billions of dollars in funding for programs in the Colorado River Basin to recycle water, increase efficiency, and competitive grants to pay water rights holders not to use water from the river are being provided by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and Inflation Reduction Act, and other programs funded through the United States Environmental Protection Agency and United States Department of the Interior. These are projected to reduce demand by hundreds of thousands of acre-feet per year.

Some experts predict climate change will cause the Colorado River Basin to become drier and warmer, with less snowfall and runoff reducing water supplies. That prospect and future projections of continued urban growth have generated significant concern over how the Colorado River will meet future water demands.

The Colorado River and the neighboring Rio Grande are now among the world’s most controlled and litigated river systems. The Colorado River is also one of the world’s most heavily regulated and hardest-working rivers.

Recreation

Rafting on the Colorado River by the National Park Service.

Recreation is also a significant part of the Colorado River system. Millions of people use the Colorado River Basin annually for activities ranging from rafting to snow sports, generating billions of dollars in revenue.

Famed for its dramatic rapids and canyons, the Colorado River is one of the most desirable whitewater rivers in the United States, and its Grand Canyon section — run by more than 22,000 people annually — has been called the “granddaddy of rafting trips.” Grand Canyon trips typically begin at Lee’s Ferry and end at Diamond Creek or Lake Mead; they range from one to 18 days for commercial and two to 25 days for private trips. Private noncommercial trips are challenging to arrange because the National Park Service limits river traffic for environmental purposes. People who desire such a trip often have to wait more than ten years for the opportunity.

Several other sections of the river and its tributaries are popular whitewater runs, and many of these are also served by commercial outfitters. The Colorado River’s Cataract Canyon and many reaches in the Colorado River headwaters are even more heavily used than the Grand Canyon, and about 60,000 boaters run a single 4.5-mile section above Radium, Colorado, each year. The upper Colorado River also includes many of the river’s most challenging rapids, including those in Gore Canyon, which is considered so dangerous that “boating is not recommended.” Another section of the river above Moab, known as the Colorado River “Daily” or “Fisher Towers Section,” is Utah’s most visited whitewater run.

Bryce Canyon, Utah, by Dave Alexander.

Eleven U.S. national parks — Arches, Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Bryce Canyon, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, Grand Canyon, Mesa Verde, Petrified Forest, Rocky Mountain, Saguaro, and Zion — are in the watershed, in addition to many national forests, state parks, and recreation areas. Hiking, backpacking, camping, skiing, and fishing are among the multiple recreation opportunities offered by these areas. Fisheries have declined in many streams in the watershed, especially in the Rocky Mountains, because of polluted runoff from mining and agricultural activities. The Colorado River’s major reservoirs are also heavily traveled summer destinations. Houseboating and water-skiing are popular activities on Lakes Mead, Powell, Havasu, Mojave, Flaming Gorge Reservoir in Utah and Wyoming, and Navajo Reservoir in New Mexico and Colorado. Lake Powell and the surrounding Glen Canyon National Recreation Area received more than two million visitors annually in 2007, while nearly 7.9 million people visited Lake Mead and the Lake Mead National Recreation Area in 2008. Colorado River Recreation employs some 250,000 people and contributes $26 billion annually to the Southwest economy.

About 40 million people depend on the Colorado River’s water for agricultural, industrial, and domestic needs. The Colorado River irrigates 5.5 million acres of farmland in a region encompassing some 246,000 square miles. Its hydroelectric plants produce 12 billion kilowatt hours of hydroelectricity each year. Hydroelectricity from the Colorado River is a crucial supplier of peaking power on the Southwest electric grid. Often called “America’s Nile,” the Colorado River is so intensively managed that each drop of its water is used an average of 17 times yearly. Southern Nevada Water Authority has called the Colorado River one of the “most controlled, controversial, and litigated rivers in the world.”

The river fuels a 1.4trillionannualeconomy.Fishing,whitewaterpaddling,boating,backpacking,wildlifeviewing,hiking,andmyriadotherrecreationalopportunitiescontributeabout1.4 trillion annual economy. Fishing, whitewater paddling, boating, backpacking, wildlife viewing, hiking, and myriad other recreational opportunities contribute about 1.4trillionannualeconomy.Fishing,whitewaterpaddling,boating,backpacking,wildlifeviewing,hiking,andmyriadotherrecreationalopportunitiescontributeabout26 billion alone.

Colorado River near its headwaters near Parshall, Colorado, by Carol Highsmith.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, May 2024.

Also See:

Grand Canyon – One of Seven Wonders

National Parks, Monuments & Historic Sites

Sources:

American Rivers

Encyclopedia Britannica

Water Education Foundation

Wikipedia