The Great Medicine Road of the Whites – Legends of America (original) (raw)

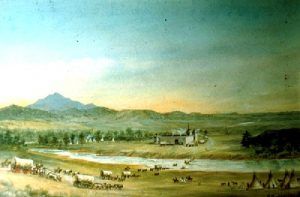

South Platt River on the Oregon Trail by William Henry Jackson.

By Grace Raymond Hebard and Earl Alonzo Brininstool, 1922.

For over a century, the Platte River had been the trail of the Indian, fur trapper, explorer, gold seeker, Mormon, soldiers, the Pony Express, the telegraph line, the stage station, the railroad, and civilization. Along the banks of this fickle, sometimes only inches deep and yards wide, then, in a night, feet deep and miles wide, with an ever-shifting sandy bottom, more people have ventured to and beyond the Rocky Mountains than along any other stream. The route was the one with the least resistance, the easiest of approach, and when once upon it, the least difficult to travel; the one the wild animals used, the one the Indians selected.

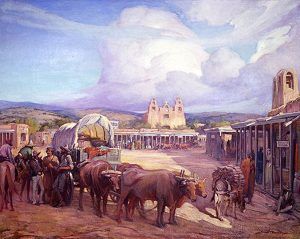

The End of the Santa Fe Trail by Gerald Cassidy, about 1910.

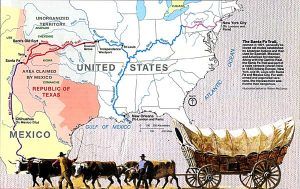

Before the Platte River route to the West was a generally used thoroughfare, the Santa Fe Trail to the South was utilized as a road of commerce to the old interior city of Santa Fe, New Mexico. This road of commerce was in its most active existence from 1822 to 1843. However, this path into Mexico had been used before 1822 by the occasional trader, and after 1843, it continued to be a merchant’s road to a limited extent. During 1843, the trail was operated as a military road and was a part of the trail for the emigrants on their way to California.

On the Santa Fe Trail, travelers encountered many hostile Indians, including the Osage, Arapaho, Pawnee, Kiowa, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Apache tribes. As the trail was 800 miles long, five times as long as any that had been put into use to that time in the United States, constant vigilance and alertness both day and night became a necessary precaution to avoid hostile Indians. In the earliest days of the traffic over the road, transportation was carried on exclusively by pack train, wagons not being used until 1824, when a train, or caravan, as it was called, of 25 wagons drawn by horses, left Independence, Missouri at the bend of the Missouri River, for the long, dusty, desert journey across the plains. The caravans started, in reality, from St. Louis, going from there to Independence, Missouri, by steamboat. Still, the land journey began many miles west of St. Louis, Missouri, near the mouth of the Kansas River.

The washing away of the bank of the Missouri River at Independence forced its abandonment as a shipping point, or starting point, on the trail, and Westport, a few miles distant, took its place in overland activities. The method of transportation by oxen was inaugurated on the Santa Fe Trail in 1829, which proved to be more profitable than horses or mules for the monotonous, dry journey seemed better fitted to the plodding. From this date, oxen hauled more than half of the traffic over the Santa Fe Trail. The transactions in merchandise were not all made at Santa Fe, New Mexico, for the caravan moved from that city down to Chihuahua, Mexico, a distance greater from Santa Fe than Santa Fe was from St. Louis. For several years, the Santa Fe Trail was not marked out. In the earlier days, the starting point was from Franklin, about 205 miles west of St. Louis. The point of land departure was changed to Independence in 1827. Westport was established in 1833, and Kansas City in 1838.

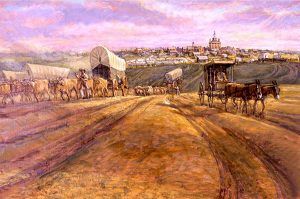

Trails Leaving Independence by Charles Goslin mural hangs in the National Trails Museum in Independence, Missouri.

The transactions in merchandise were not all made at Santa Fe, for the caravan moved from that city down to Chihuahua, Mexico, a distance greater from Santa Fe than Santa Fe was from St. Louis. For several years the Santa Fe Trail was not marked out, the train of pack horses or wagons going over no well-beaten path, but the wheels of commerce and the hoofs of the patient oxen had by 1834 cut into the sod a distinct trail, which from that time on, was closely followed. Council Grove, Kansas, 150 miles from Independence and 650 from Santa Fe, was the first noted camping ground along the trail, and the place where the council was held with the Indians. Southwest of this place, the trail went across the Cimarron Desert, the Rio Mora, the Rio Gallinas, past Wagon Mound, Las Vegas, San Miguel to Santa Fe, an illimitable stretch of barren land, of sandstorms, and dangerous desert, without a white inhabitant from Independence to Las Vegas, 50 miles east of the sleepy city at the end of the trail. To escape 60 miles of the worst part of the desert lying between the Ford of the Arkansas and Cimarron Rivers, a cut-off was made, which again took up the trail at the crossing of the Mora River. Later, this branch route was followed by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad.

Santa Fe Trail Map.

On May 15, 1831, a caravan conducted by Josiah Gregg started over the trail with a train of such magnitude and with such a variety and quantity of merchandise that his venture marked a new era in the commerce of the plains. He did not make just a single journey, but many of them, and most successfully, as witnessed in his journal, a classic for caravan travel over the Santa Fe Trail. The collection of merchandise consisted of crapes, pelisse, cloths, shawls, handkerchiefs, cotton hose, looking glasses, ginghams, velvet, cutlery, firearms, and many other commodities, the majority of which were to be exchanged for Mexican gold and silver. The oxen, raising clouds of choking dust with their awkward hoofs, traveled from 12 to 15 miles a day with the load, the return trip, with primarily empty wagons, making 20 miles daily, the caravan making a trip of two thousand miles between April and November. A well-organized wagon train contained 25 to 26 large wagons to carry from three to three and a half tons each, with six yoke of oxen to each wagon and about 30 additional oxen to take the places of disabled ones. In 1843, the trial was brought to its end through the raids by the Indians, the conspiracies of the Texas bandits, and the hostility of the Mexican government through its president, Santa Anna, who prohibited commercial relations with our country because he believed that Mexico and the United States would soon be at war. With the temporary abandonment of the Santa Fe Trail, the Oregon Trail along the Platte River became a necessity.

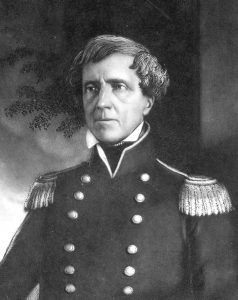

Stephen Watts Kearny.

In 1846, General Stephen W. Kearny, when the United States and Mexico had become involved in the war, used the Santa Fe Trail as a military road, thus making it a road of national importance to the government and the country to which the trail extended. The successful issue of the war, in which the trail had played a conspicuous part in military transportation, was the initial step toward the annexation in 1848 of New Mexico and Arizona, parts of Kansas and Colorado, and all of California, Utah, and Nevada. When the embargo of 1843 was lifted, commerce over the old trail was renewed and significantly increased until, during the late1860s and early 1870s, the trade over the trail amounted to more than $5,000,000. However, not all of the merchandise remained at Santa Fe, for a significant portion was sent into California over another trail, the Gila, which was extensively used by the gold-seekers of 1849 to California. The Santa Fe Road became one of commerce, war, and home seekers, all factors in developing the territory on the Pacific. Many went to Mexico and did not return to the States but pushed toward the Pacific, going over what was known as the Gila Trail, which, after leaving Santa Fe, crossed the continental divide from the valleys of the Rio Grande and the Arkansas River, south to the Gila River and west to the Gulf of California.

Another trail to the West, known as the Old Spanish Trail, went north from Santa Fe via the Colorado River, northwest across the Sevier and Virginia Rivers, skirted Death Valley, and then west to California, ending at Los Angeles. Thus, there was now established, by the union of the Santa Fe and Gila Trails, a southern transcontinental road over which Kit Carson went, in 1846, to carry a message to Washington, D.C. from General John C. Fremont, telling of the uprising of the inhabitants of California, and along which General Kearny hurried to California to assume control of the Pacific coast. The conquest of Mexico and California created new problems for the United States; no one greater than protecting and guarding these large tracts of border territory and holding firmly to our government the Americans who lived in the newly acquired lands.

Sacagawea guided Lewis and Clark on their expedition of 1804-06

The stubborn determination of the Blackfeet Indians, their home being primarily within those boundaries now embraced within the state of Montana, to avenge the killing, in 1806, of one of their chiefs by Captain Meriwether Lewis of the Lewis and Clark Expedition made the invasion by the white man along the upper Missouri River one of unusual danger. It is to be remembered that Lewis and Clark had been sent by the United States government in 1804 to explore the sources of the Missouri River and to blaze a trail, if possible, to the Pacific Ocean. After reaching the headquarters of Missouri and crossing the Rocky Mountains, the expedition reached the Pacific coast, where it spent the winter of 1805-6. The expedition finally returned to St. Louis, and Captain Clark explored the Yellowstone River. At the same time, Captain Lewis went north to search for the headwaters of the Marias River, a branch of the Missouri. Captain Lewis, with his small escort of white men, was attacked while in his exploration of the sources of the Marias River by the Blackfeet when self-preservation demanded the life of the attacking chief. From the time of the killing of this chief by Lewis, until the Indians were obliged to confine themselves within the boundaries of an Indian reservation, the Blackfeet looked upon the white man as their natural enemy and treated him as a hereditary foe. The acts of hostility of this tribe drove many explorers and fur hunters to a safer and more southern route than that of the Missouri River. The Platte River afforded alluring possibilities, a shorter road, fewer Indian troubles, and, in earlier days, a new field for obtaining the precious beaver skins. When the Platte River, particularly the northern branch, was explored, it became a thoroughfare for hundreds of thousands on their way to the West, seeking adventure, furs, fortunes, and homes.

It was the vengeful spirit of the Blackfeet Indians that prevented the Astoria Expedition, sent west by John Jacob Astor under the leadership of Wilson Price Hunt in 1811, from going to the sources of the Missouri River and then through the Rocky Mountain pass discovered by the little Shoshone Indian guide, Sacajawea of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Hunt and his men left St. Louis early that year to go to the mouth of the Columbia River to establish a fur post that was the headquarters for oriental trade. Warnings were given to Hunt by friendly Indians when he and his party had reached, by the way of the Missouri, the country not far from the hunting grounds of the Blackfeet, that to push on farther up the river would be to invite immediate death, for the Blackfeet were remembering with intense hostility the death of their chief. The retreat was not to be considered; advance seemed unwise; variation from the scheduled route seemed a means of escape and, at the same time, a possible method of continuing toward the West, though no white man had ventured so far over this new route toward the setting sun as Hunt and his men now expected to go. To the southwest, the company headed itself, in place of the northwest of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, in a few days, reaching what is now the northeastern boundary of Wyoming. The party crossed the Powder River country, which, in a half-century, was to become the bloody field of fierce and decisive Indian wars.

Bozeman Trail, Montana by Kathy Alexander.

The Bozeman Trail through or over the Big Horn Mountains to the Wind River and its eternally snow-capped mountains, to the passes south of Yellowstone Park, not difficult to travel; in the shadow of the majestic Teton Peaks, which at that time were called the “Three Brothers” or “Pilot Knobs,” and then to the Snake River, the Astorian party journeyed toward the Pacific. Down the Snake River, the party wended its way; down the Columbia River to its mouth, a site was selected on which the historic fur post or fort was built as “Astoria.” On the return of the Astoria men under the leadership of Robert Stuart, in 1812, when they were east of the present boundary between Idaho and Wyoming, a well-beaten Indian trail was discovered and followed for a few days.’ The fear of encountering Indians at the end of this trail caused the little depleted band of wearied men to deflect from the outgoing route and strike out for the South instead of turning through or into the neighborhood of Union Pass. In the course of a few days, the men arrived in the neighborhood of a rift in the Rocky Mountains, which was in time to be known as South Pass, through which the trains of emigrants on the road to the West were obliged, in follow ing years, to pass. Striking the Sweetwater west of Devil’s Gate, the Astorians followed down the North Platte River to its junction with Poison Spider Creek, 18 miles west by South of Casper, Wyoming. They constructed a log cabin here, expecting to spend the winter of 1812-13 in a secluded spot. However, after being discovered by Indians, the band of white men pushed down the North Platte River, arriving at St. Louis in the spring of 1813. Thus, we now have the first organized party of white men to use the Indian road that was to become the trail to the West for the white men and to be known as the Oregon Trail, which the Indians, in time, called “The Great Medicine Road of the Whites.”

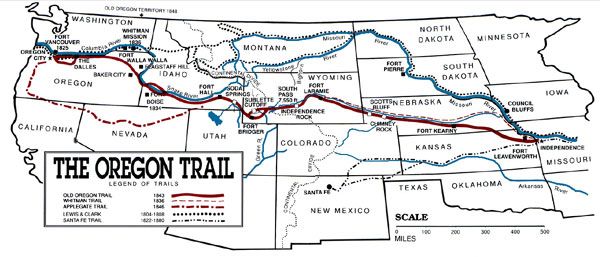

Oregon Trail Map.

This trail was also known by the names “The Overland Trail,” “The Mormon Trail,” “The Emigrant Road,” “The Salt Lake Route,” and “The California Trail.” These first explorers along the Platte River and their finding of a new overland way to the West directly link them with the present narrative of the Indians’ stubborn, persistent, and, at some times, successful battles and raids against the white man and his invasion into their hereditary hunting grounds. It mattered not to the red man if his natural foe were headed toward the West for furs, a home in the Oregon country, gold in California and Montana, or silver in Nevada; it was an invasion. When, in the early 1860s, gold was discovered in Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, and Wyoming, the stampede over the Oregon Trail to the new gold fields only added to the Indian’s wrath and his war paint, the red man realized that the whites were not only to invade his cherished hunting grounds but take possession of them. To thoroughly appreciate the white man’s motive for trespass and understand the red man’s bitter and persistent fighting, some detailed descriptive material is necessary. The earliest group of white men to trap in those streams, which run parallel with the Oregon Trail or were crossed by that road, belonged to William Ashley’s Rocky Mountain Fur Company from St. Louis, which was formed to trade in and trap for beaver skins in the Rocky Mountains.

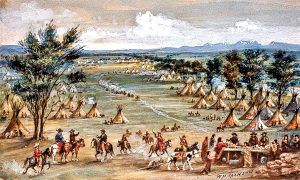

Rocky Mountain Rendezvous by William Henry Jackson.

Under Ashley’s management, in 1822, a fur company was organized to go into the mountains to trap and trade. Among other members of Ashley’s organization were Andrew Henry, Jedediah S. Smith, William Sublette, Milton Sublette, David E. Jackson, Robert Campbell, James Bridger, Etienne Provost, and many others, all of whom wrote their names prominent in the early history of the West. Lakes, streams, mountain passes, peaks, forts, and cities bear testimony to their indomitable bravery. Their leader sent the men into an unexplored Yellowstone and Big Horn region, reaching the country by the Missouri River route. In 1824, under the leadership of Thomas Fitzpatrick, the men went southward to explore the headwaters of the Big Horn and Wind Rivers from these upper valleys. While on this journey over unbeaten paths, the white men discovered South Pass, a wide passageway between the lands drained by streams flowing toward the Atlantic and those that flowed toward the Pacific. This gateway was easy of passage, its ascent and descent so gradual as to be hardly perceptible, yet its significance on the road to the West was vital by unlocking the mountains that had been a barrier between the East and the West. The distinction of being the first white man to utilize South Pass seems to belong to Thomas Fitzpatrick, who, with his party in the spring of 1824, while seeking an opening in the Rocky Mountains, discovered that rift that gave easy passage to the country West of this ridge. From South Pass, Ashley’s little band of fearless fur men journeyed down the Big Sandy River to its junction with the Green River, a site that soon, and also in years to come, was to witness strange scenes enacted by men of courage and daring, who had temporarily isolated themselves from civilization.

Mountain Man Rendezvous.

The place became known as the “Green River Rendezvous.” Technically, Ashley was the first to use the word “rendezvous” to indicate a locality where we were to gather the hardy fur men on a large scale. On July 1, 1825, Ashley met his men who had been collecting beaver skins in an area between the 34th and 44th degree of latitude on the Big Horn, Sweetwater, Green, and Bear Rivers, on the banks of the Green River about twenty miles north of the present Utah-Wyoming boundary line. In this collected assemblage were twenty-nine fur trappers of the Hudson’s Bay Company, who, with Ashley’s trappers, gathered together 120 men, divided into two camps. The site of this historic meeting is easy to identify today, and it is an area of 200 acres known as Bridger’s Flat. The rendezvous was a selected site at which the yearly contracts between fur traders and fur trappers were made and former contracts settled. In the years to follow, every trapper knew where the rendezvous would be held, and about July 1 each year, they began to gather. “Here would come gaily attired gentlemen from the mountains of the South, with the Mexican about them, their bridles heavy with silver, their hats rakishly pinned with gold nuggets, and with Kit Carson or Dick Wooton in the lead. In strong contrast would appear Jim Bridger and his band, careless of personal appearance, despising foppery, burnt and seamed by the sun and wind of the western deserts, powdered with alkali dust, fully conscious that clothes mean nothing, and that, man to man, they could measure up with the best of the mountain men. At this gathering, you would find excitable Frenchmen looking for guidance from Provost, the two Sublettes, and Fontenelle, the thoroughbred American, Kentuckian in type, with his long, heavy rifle, his six feet of bone and muscle, and his keen, determined, alert vigilance; the canny Scot, the jolly Irishman, best represented by Thomas Fitzpatrick, the man with the broken hand, who knew more about the mountains than any other man, except possibly Bridger; and mixed in the motley crowd an alloy of Indians — Snake, Bannock, Flathead, Crow, Ute — come to trade furs for powder, lead, guns, knives, hatchets, fancy cloth, and, most coveted of all, whiskey, that made the meanest redskin feel like a great chief.”

South Pass, Wyoming.

Ashley, in his expedition of 1825-26, had a two-wheeled cannon taken through South Pass to one of his fur posts in the neighborhood of the Great Salt Lake. The wheels of this engine of war made the first dim traces of vehicles along the Oregon Trail — the trail that would lead to peaceful possession of the Oregon country in the years soon to follow. In 1826, Ashley sold his interests in his fur company to Jedediah Smith, David Jackson, and William Sublette. Again, in August 1830, this newly organized company passed into the control of Fitzpatrick, Bridger, Milton Sublette, Henry Fraeb, and Baptiste Gervais, who operated until 1834 under the name of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. In 1835, contracts were made to transfer the company’s possessions to Lucien Fontenelle, representing a rival company known as the American Fur Company. This company used a recently constructed fur post situated on the Laramie River as headquarters for trading in furs, which soon became known all along the trail as Fort Laramie.

Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville.

Allured by the vast wealth accumulated by William Ashley from his fur expeditions, Captain Benjamin Bonneville, on a leave of absence from the United States Army, marched, in 1832, over the old trail which was then in its beginning, with an escort of 110 men, and 20 wagons drawn by oxen and mules. The clanking chains, the creaking wagons, and the costly trappings for the horses made a deep impression on the Indians, who, waiting to see the train pass in review, wondered if the white men were invaders into their treasured hunting grounds or if they were only passing on to other fields. To the perplexed Indians, the deep marks made by hoof and wheel were ugly scars on the face of their traditional hunting ground. Bonneville, from 1832 to 1835, made many expeditions in the country north and South of the South of Ashley’s party and followed along the entire length of the Oregon trail, using the route to Fort Vancouver, Washington, which Jedediah Smith had discovered while exploring the Pacific coast. Though no fortunes were made, Bonneville, the scholarly fur trader, contributed, by his wonderful maps and surveys, a vast amount of valuable information to our government regarding the geography of the country and the sources of many important streams in the territory he had explored. Nathaniel J. Wyeth, a merchant from Cambridge, Massachusetts, became ambitious in establishing fur posts on the Pacific. Though this plan was not as ambitious as John Jacob Astor’s, the purpose was the same: trading with the Orient.

Traveling over the entire length of the Oregon Trail from Independence to Vancouver, Washington, Wyeth, from 1832 to 1836, explored many new places, but to his special credit was the erection in 1834 of Fort Hall, Idaho, a fur post on the trail situated on the left bank of the Snake River near the mouth of the Portneuf River in Idaho. As with Bonneville, Wyeth lacked adequate preparation for exploring unknown territory, which Ashley possessed to a marked degree. His early training in no way qualified him for the financial adventure. His lack of success may also be attributed to the failure of our government to understand its interests in the Pacific and to realize the methods the Hudson Bay Company used against any American who attempted to obtain a foothold in the Oregon country. Accompanying Wyeth to the West in 1834 were many people, the most prominent of the group being Jason and Daniel Lee, Cyrus Shepard, C.M. Walker, and P. L. Edwards, missionaries who had been sent into the wilderness to preach and teach the Indians living south of the Columbia River; Captain William Stewart, a veteran under Lord Wellington at Waterloo, who was traveling for pleasure; Thomas Nuttall, a botanist, and J.K. Townsend, an ornithologist. In the following years, the missionaries and others of Wyeth’s party settled in the Willamette Valley, built homes, cultivated the soil, and became the nucleus of Americans who were to wrest from the British authority in the Oregon country. Following the Lees’ religious zeal to help Christianize the Indians.

Marcus Whitman founded the Waiilatpu Mission in southeastern Washington in 1836. The mission was shown in a painting by William.H. Jackson in 1865.

In 1835, Reverend Samuel Parker and Dr. Marcus Whitman, led through the mountains by the indomitable Fontenelle, went over the trail toward the Oregon country. When the party traveled through South Pass, Parker remarked that there would be no difficulty constructing a railroad from the Atlantic to the Pacific, so gradual was the grade through the pass. Among those at a Green River Rendezvous, many Indians from many tribes were assembled, all begging for the “Book of Heaven,” as they called the white man’s Bible. Finding many Indians desirous of obtaining religious instruction, Dr. Whitman decided that two men were insufficient to do the teaching and sent Parker, the older man, on into the wilderness with Jim Bridger for a guide. In contrast, the younger man retraced his steps back to the East to obtain recruits for religious educational work. The following spring, Whitman, with his bride, and Reverend H.H. Spalding, with his bride, went back to the East to obtEastrecruits for the religious work. When the little party, on July 4, 1836, arrived at South Pass, Whitman went through the formality of taking that part of our country in the name of God and our government. Over the Oregon Trail, their wagon journeyed, the wheels marking the road more indelible, but the great significance of these deeper ruts was that they were made by wheels that were carrying white women to the West, the first white women to go over the trail, and unmistakable sign of the possession of the land on which were to be built homes by Americans in Oregon.

As a result of the establishment of these homes, the Whitman party of 1836 was followed by another wagon train in 1843, commanded by Dr. Marcus Whitman, who had once more returned to the Atlantic, the largest and most important train that had, to this time, ventured over the trail. In the train were over 200 wagons, 1,000 cattle, many men and women, and numerous children who would be the future citizens of a free American commonwealth on the Pacific coast. The wagons of this long train traversing the entire length of the Oregon Trail were loaded with farm implements, grain for seed, and the more choice pieces of household furniture saved from the gradual lightening of the load along the road. In Oregon, 43 efforts were made by the Americans, places of worship were constructed, schools were started, the soil was cultivated, and a small printing press was put to work to help mold public opinion. The American with his family had come to stay. The Hudson Bay Company now realized the seriousness of the problem regarding which nation, England or the United States, was to possess the rich valleys of the Oregon country.

John C. Fremont by Ehrgott, Forbriger and Co

The first government expedition over the trail was conducted by John Charles Fremont in 1842 when he did a preliminary survey for a possible transcontinental railway. Fremont made five expeditions into the West to find passes in the mountains through which a railroad could be constructed, three of them for our government and two financed by private means. The first was the Wind River Mountain Expedition of 1842; the second was the Salt Lake, Columbia, and California Expedition of 1843-44, in both journeys using a significant portion of the Oregon Trail for transporting men and equipment. To bring the Pacific nearer to the Missouri River, to hold the territory on the coast in close relation with our government by railway transportation, and to help keep the people west of the Rocky Mountains loyal citizens of our union people who were to develop the rich land in the West, were the missions assigned to Fremont. From Fremont’s reports, which the government printed and distributed in great numbers, many emigrants gained a favorable impression of the West and, as a direct result, sought homes beyond the Rocky Mountains, their route to the coveted lands primarily over the Oregon Trail.

Into the hands of Brigham Young came this printed information, which was primarily responsible for his selection of Utah. as a home for his followers. The Mormons and those who sought homes beyond Utah did their part in making this road more enduring and easier to travel. Fremont also made a valuable set of topographical maps of the country he traveled, the data used for distances along the trails in locating streams and mountains in the government pamphlet. The Oregon Trail was, in reality, now a national road, though the government never contributed a cent to its construction or preservation. It was a national road of opportunity and the longest single road in history.

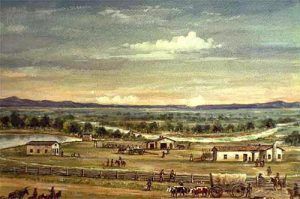

Old Fort Laramie, Wyoming.

On the Oregon Road, in 1842, there were but four buildings between Independence, Missouri, and Vancouver, Washington, and these were not homes but fur trading posts — Fort Laramie, Fort Bridger, Fort Hall, and Fort Boise. No engineer placed his transit or rod on this road; no grade was established; no bridge was built over the streams crossing its path; no fills were made; no mountain passes surveyed, yet Father De Smet pronounced the trail one of the finest highways in the world. Now the road which had been a path for the wild animal, the tepee footway for the Indian, the trail of the trapper and the road of the home-seeker, became so deep, so wide, so easy to travel that it might well have been called the Broad Highway to the West. General W.F. Raynolds, although seeking the Oregon Trail on his way South in 1859. Traveling on the Northwest side of the Big Horn Mountains, he feared that his expedition might cross the old trail and not know of its existence! He acknowledges his error by saying: “Before starting, I had, in my ignorance, asked Bridger (his guide) if there was any danger of crossing the road without knowing it. I fully understand his surprise, as it is as well marked as any turnpike at the East. It was dry and dusty, showing the immense travel over it.

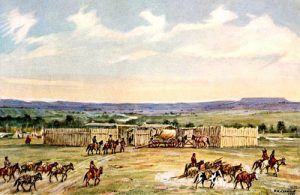

Fort Kearny, Nebraska.

They generally traveled in parties of two or three for the company more than for safety considerations. No wonder the white man was eager to push on beyond the firing line of civilization by using this road. No wonder the red man persisted in saying that his lands should not be utilized by dividing them by the “Medicine Road.” That the Indian frequently came into conflict with the white man as he drifted back and forth with the season, on either side of the trail on the annual hunt, was an inevitable consequence of frontier conflict for the control of the land. After his first expedition to the Rocky Mountains via the Oregon Trail, General John Charles Fremont strongly recommended to our government that military forts should be established along the Oregon Trail. Not to protect the settlers in the regions of the forts, for there were no such hardy people along the road, but to assist and guard the Americans and their trains of wagons on their way to the West, who were to help in the development of the Oregon country. Of the four forts finally taken over by our government and garrisoned by regular soldiers who safeguarded the lives of those, venturesome and daring, on their way to the West, no one was so important and became so well known for its romance and tragedy, as Fort Laramie. Mainly upon the recommendation of Fremont, Congress established along the Oregon Trail to protect 2,020 miles of road and four forts, including Fort Kearney, Nebraska, in use 1847, purchased 1849, 316 miles from Independence, on the Platte near Grand Island; Fort Laramie, Wyoming, 351 miles from Fort Kearney, a fur post in 1834, purchased in 1849, situated near the junction of the Laramie with the Platte Rivers; Fort Bridger, 403 miles from Fort Laramie, established by Jim Bridger in 1842 as a repair and blacksmith shop for the emigrants in the valley of the Black Fork, a tributary of the Green River, used as a military post from 1858 to 1890; Fort Hall, Idaho, situated 218 miles from Fort Bridger, 732 miles from Fort Vancouver, on the right bank of the Snake, nine miles above the mouth of the Portneuf, built-in 1834 by Wyeth as a fur post four military stations, each hundreds of miles apart, in the heart of the tribes of hostile Indians. No wonder the Indians had a slight fear of the soldiers and little respect for a government that had such a limited knowledge of Indian warfare and unprotected trails into the undeveloped West. Those daring white men who plied the first fur trade in the West along the Oregon Trail went up the Missouri River as far north as where the Platte River joined it in Omaha, Nebraska. From here, the route West was along the south side of the Platte River to the junction of the north and south branches of the river.

Wagon Train.

At an early date in fur trading over the Oregon Trail, a more direct road was established by a cut-off that abandoned the Missouri River not far from Independence and went to the northwest by crossing the Kansas, Big, and Little Blue Rivers, reaching the Platte River about 20 miles below Grand Island, the distance to this point from Independence being 316 miles. The Santa Fe and Oregon Trails were the same for 41 miles west of Independence; at this point, the two roads separated, one going southwest to Santa Fe and the other to the northwest to the Pacific. The directions on a signboard at the point of deviation read: “This Road to Oregon” — not too-detailed instructions for 1,979 miles of travel through many tribes of hostile Indians, across countless streams, over treeless prairies, and numerous mountain passes! From where the Oregon Trail met the Platte River, the road continued on the south side of the stream and also along the south side of the North Platte River, to the northwest, passing the two historic landmarks, Chimney Rock and Scott’s Bluffs in Nebraska to Fort Laramie, Wyoming a place of rest, protection, repairs, and supplies having been erected in 1834 by William L. Sublette as a fur storehouse rather than a fortification against hostile Indians. From Fort Laramie, the trail went northwest to the big bend in the North Platte River, near present-day Caspar, Wyoming, down the west side of the Platte River, but not following it, the road crossed the Sweetwater River at Independence Rock, then directly west to Devil’s Gate, a rift in the mountains through which all of the wagons had to go which traversed the Oregon Trail, to Split Rock and South Pass. This was the halfway point between Independence and Vancouver, the streams east of the pass flowing toward the Atlantic, those west toward the Pacific.

Fort Bridger, Wyoming.

In the earlier days, before Fort Bridger was built, the Oregon Trail went southwest to Pacific Springs, across the Little and Big Sandy to the Green River, and then northwest to Snake River. Early in the use of the trail, the road from Pacific Springs deflected its course to the southwest to Black’s Fork near its junction with Ham’s Fork, where James Bridger had erected a blacksmith shop and repair station for the emigrants, known as Fort Bridger. In place of always stretching to the southwest, to save time and many miles, there was established a branch of the Oregon Trail known as the “Sublette Cut-off,” which left the main trail at Little Sandy, taking a direct route to the west crossing Big Sandy and Green River then to Bear River where it blended with the road coming from Fort Bridger. Though this shortcut saved 53, the emigrants missed Fort Bridger, where supplies and repairs could be obtained. From the fort, the trail went to Fort Hall, Idaho, where it reached the waters of the Columbia River, west to American and Salmon Falls, to Fort Boise, and then directly northwest to the Columbia River. It continued west on the south side of the river to the Dalles from the Cascades to Fort Vancouver opposite the mouth of the Willamette River.

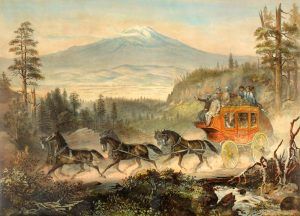

Overland Mail stagecoach in the mountains by Rey & Britton.

The Oregon Trail, hazardous though not difficult to travel, had no intervening stations between Fort Laramie and Fort Bridger until the Pony Express and stagecoaches came. In the 1860s, these stations were constructed not to house or protect the whites but to exchange tired horses for fresh ones. This trail had to be used to go to Oregon, California, Nevada, Idaho, or Montana. The constant procession of emigrants over this road, coming from the country East of theEastsouri River, caused the Indians to wonder and ponder. Placing their hands upon their mouths, they called the trail “The Great Medicine Road of the Whites,” believing that the lands from when the white man came must now be empty, so great was the exodus to the West. At first, the Indians did not object to this invasion over his traditional trail, which he used when in quest of game or as a more permanent trail to places for water. Ultimately, a time came when protests from the red man became so forceful in the way of ambush, raids, and open conflict against the white man that those who went over the “Medicine Road” now had to go in groups and by force, of firearms passed over the coveted trail. Had it not been for the hostilities committed by the Indians along the Oregon Trail and the frequent depredations upon parties of emigrants going West, this road would have been in use to exclude any other until the advent of the Union Pacific Railroad.

To avoid the hostilities of the Indians, a road along the South Platte River was established and called the Overland Route, though contrary to expectations, the raids were as numerous and depredations as serious as along the old trail. The old road by way of Fort Laramie, the North Platte, Sweetwater, and Fort Bridger, with the coming of the iron trail, was abandoned in 1869, although the unnumbered feet, hoofs, and wheels have made indelible this route; the road today being easily traced and the furrows accurately followed for miles along the North Platte and Sweetwater Rivers. No especially accurate record has been kept of the number of human souls trudging over this road during the long years of its operation. However, the record for the year 1852 has been quite accurately estimated during that one year, amounting to over 51,000.

Oregon Trail Re-enactors.

The Overland emigration on the Oregon Trail in 1846 was unending, though never outnumbering those who, in 1849, scrambled in seeming madness over the road to the gold fields of California. Many who sought health and wealth in the country at the end of the trail failed to reach their destination; the number of graves along the trail were silent witnesses in the testimony of the battle for territorial expansion. In 1849, 4,200 died on the plains, while cholera, in 1852, which followed in the path of the emigrants, claimed 5,000 as enough graves to mark the entire trail every half mile for over 2,000 miles. To cover these 2,000 miles took four months under the most favorable weather conditions and method of transportation and six months if out of luck. The tide of emigrants in 1843 to Oregon was so large that the Americans could set up a provisional government, providing for joint occupancy of that country. The colony that had settled in the Willamette Valley drew up and adopted a code of action before our government had obtained title to the land. That the pioneers of the trail peacefully settled the question of possession of the Oregon country is evidenced by the fact that the Hudson Bay Company not only accepted the terms of the compact for a provisional government but, through taxation, added to the financial support of the settlement. By the treaty of 1846 with England, the Oregon country was ceded to the United States. In 1848, the territory of Oregon was organized, embracing the lands that now are in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, as well as parts of Montana and Wyoming. Thus, the Oregon Trail helped to win an empire for the United States. The ultimate possession of the Oregon country had been left to that race that should first occupy the territory. The Hudson Bay Company brought its people from the Red River of the North. Still, the Oregon Trail brought American wagons and home seekers, which settled the Oregon question once and for all. The old trail had won.

The egress to the West feverishly continued all through the 1860s until the Union Pacific Railroad was constructed, as the following extracts from the diary of Sergeant Isaac B. Pennick, 11th Kansas Cavalry, written between May and September 1865, while a member of the Wind River Expedition, will demonstrate:

South Platte River, Colorado.

“.. arrived before sun August 17, (1865) down five miles below Julesburg, Colorado on the bank of South Platte River. Camped for the night. Hundreds of wagons along the river, ox trains, mule trains, horse trains, and pony trains in abundance; everything looks lively and brisk. “August 19 — March at 5 a.m. today, making, since leaving crossing at Julesburg, 615 in number, and with what were camped around that post, about 1,000. “August 20 — Sunday. Remain in camp today. About 175 wagons passed along today. “August 21 — Reveille at two o’clock a.m. March, a little before sunrise, met 280 wagons going west today. “August 22 — Reveille at 3 a.m. and staff. Met General Dodge 250 wagons passed today. “August 26 — Marched one half an hour before sunrise about ten miles… a large train of Mormon emigrants camped alongside us at noon.” Thus was the invasion of the West and the continuation of the Indians’ paradise. Little wonder that the red man imagined the East was beEastrapidly depopulated!

By Grace Raymond Hebard and Earl Alonzo Brininstool, 1922. Compiled Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2024.

About the Authors: Grace Raymond Hebard and Earl Alonzo Brininstool were Western historians in the early 20th century. This account was excerpted from their book, The Bozeman Trail: Historical Accounts of the Blazing of the Overland Routes Into the Northwest, published by the Arthur H. Clark Company in 1922. The article on these pages is not verbatim, as it has been very briefly edited, primarily for spelling and grammatical corrections.

Also See:

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West