The Great Migration – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Mississippi Moving Day by Marion Post Wolcott, 1940.

The Great Migration was one of the largest movements of people in United States history. Also known as the Great Northward Migration or the Black Migration, approximately six million African Americans moved from the American South to Northern, Midwestern, and Western states roughly from the 1910s until the 1970s.

When the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863, more than 90% of the African American population lived in the American South, making up most of the population in three Southern states, namely Louisiana, South Carolina, and Mississippi. This began to change over the next decade; by 1880, migration was underway to Kansas. The U.S. Senate ordered an investigation into it, and in 1900, about 90% of Black Americans still lived in Southern states.

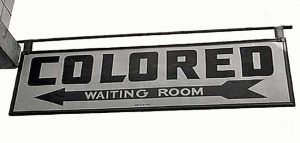

Colored Sign.

Poor economic and social conditions substantially caused it due to prevalent racial segregation and discrimination in the Southern states where Jim Crow laws were upheld. It was exacerbated by indentured servitude and convict leasing by the limitations of sharecropping, farm failures, and crop damage from the boll weevil. In particular, continued lynchings (nearly 3,500 African Americans were lynched between 1882 and 1968) motivated a portion of the migrants as African Americans searched for social reprieve.

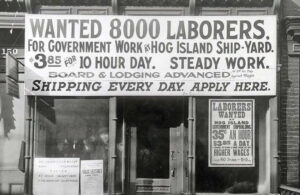

Places to move included encouraging reports of good wages and living conditions that spread by word of mouth and appeared in African American newspapers. With advertisements for housing and employment and firsthand stories of newfound success in the North, the Chicago Defender became one of the leading promoters of the Great Migration. In addition to Chicago, other cities that absorbed large numbers of migrants include Detroit, Michigan; Cleveland, Ohio; and New York City, New York. The pull of jobs in the North was strengthened by the efforts of labor agents sent by Northern businessmen to recruit Southern workers. Northern companies offered special incentives to encourage Black workers to relocate, including free transportation and low-cost housing.

Infantry soldiers in World War I.

This migration is often broken into two phases, coinciding with the participation and effects of the United States in both World Wars.

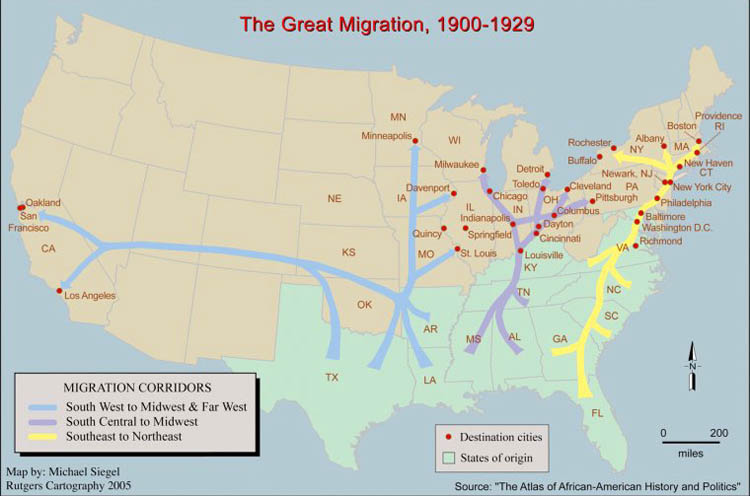

During the First Great Migration from 1910 to 1940, Black Southerners relocated to the then-largest cities in the United States, including New York City, New York; Chicago, Illinois; Detroit, Michigan; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Los Angeles, California; Cleveland, Ohio; and Washington, D.C. At a time when those cities had a central cultural, social, political, and economic influence over the United States. There, African Americans established culturally influential communities of their own.

Initially, southern elites seemed unconcerned, and industrialists and cotton planters saw it as a positive, as it was siphoning off surplus industrial and agricultural labor. As the migration picked up, however, southern elites began to panic, fearing that a prolonged Black exodus would bankrupt the South, and newspaper editorials warned of the danger. White employers eventually took notice and began expressing their fears. White Southerners soon began trying to stem the flow to prevent the hemorrhaging of their labor supply, and some even began attempting to address the poor living standards and racial oppression experienced by Southern Black people to induce them to stay.

As a result, southern employers increased their wages to match those in the North, and some individual employers even opposed the worst excesses of Jim Crow laws. When the measures failed to stem the tide, white southerners, in concert with federal officials who feared the rise of Black nationalism, cooperated in attempting to coerce Black people to stay in the South. The Southern Metal Trades Association urged decisive action to stop Black migration, and some employers undertook serious efforts against it.

When the World War I effort ramped up in 1917, more able-bodied men were sent to Europe to fight, leaving their industrial jobs vacant. The labor supply was further strained by a decline in immigration from Europe and standing bans on people of color from other parts of the world. Labor shortages in northern factories resulted in thousands of jobs in steel mills, railroads, meatpacking plants, and the automobile industry.

There were many advantages to Northern jobs compared to Southern jobs, including wages that could be double or more. The southern sharecropping system, an agricultural depression, and flooding also motivated African Americans to move to the northern cities.

Although the migrants found better jobs, many faced injustices and difficulties after migrating. The Red Summer of 1919 was rooted in tensions and prejudice that arose from white people having to adjust to the demographic changes in their local communities.

With the migration of African Americans Northward and the mixing of White and Black workers in factories, the tension was building, primarily driven by White workers. The American Federation of Labor advocated the separation between European Americans and African Americans in the workplace. There were non-violent protests, such as walk-outs in protest of having Blacks and Whites working together. As tension was building due to advocating for segregation in the workplace, violence soon erupted.

East St. Louis Riot, 1917, by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

In 1917, the East St Louis, Illinois Riot, known as one of the bloodiest workplace riots, had between 40 and 200 killed, and over 6,000 African Americans were displaced from their homes. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) responded to the violence with a march known as the Silent March. Over 10,000 African American men and women demonstrated in Harlem, New York. Conflicts continued post World War I, as African Americans continued to face conflicts and tension while African American labor activism continued.

In the late summer and autumn of 1919, racial tensions became violent and came to be known as the Red Summer. This period was defined by violence and prolonged rioting between Black and White Americans in major United States cities. Reasons for the violence varied, and affected cities included Washington, D.C.; Chicago, Illinois; Omaha, Nebraska; Knoxville, Tennessee; and Elaine, Arkansas.

The race riots peaked in Chicago, with the most violence and death occurring there during the riots. Many factors led to the violent outbursts after many Black workers had assumed the jobs of white men who went to fight in World War I. As the war ended in 1918, men returned home to find out their jobs had been taken by Black men who were willing to work for far less. By the time the rioting and violence had subsided in Chicago, 38 people had lost their lives, with 500 more injured. Additionally, $250,000 worth of property was destroyed, and over a thousand people were left homeless.

African Americans arrived in Chicago, Illinois, in 1911.

In cities such as Newark, New Jersey; New York City, New York; and Chicago, Illinois, African Americans became increasingly integrated into society. The divide became increasingly indefinite as they lived and worked more closely with European Americans. This period marked the transition for many African Americans from lifestyles as rural farmers to urban industrial workers.

This migration led to a cultural boom in cities like Chicago and New York. In Chicago, the neighborhood of Bronzeville became known as the “Black Metropolis.” From 1924 to 1929, the “Black Metropolis” was at the peak of its golden years. Many of the community’s entrepreneurs were Black during this period. “The foundation of the first African American YMCA took place in Bronzeville and worked to help incoming migrants find jobs in Chicago.”

The “Black Belt” geographical and racial isolation of this community, bordered to the North and East by whites and to the South and West by industrial sites and ethnic immigrant neighborhoods, made it a site for studying the development of an urban Black community. For urbanized people, eating proper foods in a sanitary, civilized setting such as the home or a restaurant was a social ritual indicating respectability. The people native to Chicago had pride in the high level of integration in Chicago restaurants, which they attributed to their unassailable manners and refined tastes.

Since African-American migrants retained many Southern cultural and linguistic traits, such cultural differences created a sense of “otherness” regarding their reception by others living in the cities. Stereotypes ascribed to Black people during this period and ensuing generations often derived from African-American migrants’ rural cultural traditions, which were maintained in stark contrast to the urban environments in which the people resided.

Migration patterns of African Americans from 1900 to 1929, courtesy Digital Public Library.

The massive stream of European emigration to the United States, which began in the late 19th century and waned during World War I, slowed to a trickle with immigration reform in the 1920s. As a result, urban industries were faced with labor shortages. A substantial internal population shift among African Americans addressed these shortfalls, particularly during the World Wars when defense industries required more unskilled labor.

Although the Great Migration slowed during the Great Depression, it surged again after World War II, when migration rates were high for several decades.

African Americans from Florida are making their way to New Jersey by Jack Delano, 1940.

Seeking better civil and economic opportunities, many blacks were not wholly able to escape racism by migrating to the North, where African Americans were segregated into ghettos, and urban life introduced new obstacles. Newly arriving migrants even encountered social challenges from the black establishment in the North, which tended to look down on the “country” manners of the newcomers.

In the first Great Migration (1910–40), about two million Black people left the South for northern industrial cities.

The Great Depression wiped out job opportunities in the northern industrial belt, especially for African Americans, and caused a sharp reduction in migration. In the 1930s and 1940s, increasing mechanization of agriculture virtually ended the institution of sharecropping that had existed since the Civil War in the United States, forcing many landless Black farmers off the land.

The Second Great Migration (1940–70) began after the Great Depression and brought at least five million people — including many townspeople with urban skills — to the North and West.

As a result, approximately 1.4 million Black Southerners moved north or west in the 1940s. They mostly moved from Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, and Georgia.

World War II expanded the nation’s defense industry and many more jobs for African Americans in other locales, again encouraging a massive active migration until the 1970s. Within 20 years of World War II, a further three million Black people migrated throughout the United States.

A worker at Douglas Aircraft Company in Los Angeles County, California, about 1945.

Big cities were the principal destinations of southerners throughout the two phases of the Great Migration. In the first phase, eight major cities attracted two-thirds of the migrants: New York and Chicago, followed by Philadelphia, St. Louis, Detroit, Kansas City, Pittsburgh, and Indianapolis. The Second great Black migration increased the populations of these cities while adding others as destinations, including the Western states. Western cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, Phoenix, Denver, Seattle, and Portland also attracted many African Americans.

African Americans who migrated in this second phase were met with housing discrimination, as localities had started to implement restrictive covenants and redlining, which created segregated neighborhoods but also served as a foundation for racial disparities in wealth in the United States.

Clear migratory patterns linked particular states and cities in the South to corresponding destinations in the North and West. Almost half of those who migrated from Mississippi during the first Great Migration ended up in Chicago, while those from Virginia tended to move to Philadelphia. These patterns were mostly related to geography, with the closest cities attracting the most migrants (such as Los Angeles and San Francisco receiving a disproportionate number of migrants from Texas and Louisiana).

Black Americans were not the only group to leave the South for Northern industrial opportunities. Large numbers of poor whites from Appalachia and the Upland South made the journey to the Midwest and Northeast after World War II, a phenomenon known as the Hillbilly Highway.

African-Americans traveling in Elizabeth City, Florida by Jack Delano, 1940.

African Americans from the South also migrated to industrialized Southern cities and northward and westward to war-boom cities. There was an increase in Louisville, Kentucky’s defense industries, making it a vital part of America’s effort into World War II and Louisville’s economy. Industries ranged from producing synthetic rubber, smokeless powders, artillery shells, and vehicle parts. Many industries also converted to creating products for the war effort, such as Ford Motor Company converting its plant to produce military jeeps. The company Hillerich & Bradsby initially made baseball bats and then converted their production into making gunstocks.

During the war, the defense industry had a shortage of workers. African Americans took the opportunity to fill in the industries’ missing jobs during the war, with around 4.3 million intrastate migrants and 2.1 million interstate migrants in the Southern states. The defense industry in Louisville reached a peak of roughly over 80,000 employees. At first, job availability was not open for African Americans, but with the growing need for jobs in the defense industry and the Fair Employment Practices Committee signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Southern industries began to accept African Americans into the workplace.

Renaissance Ballroom in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan, New York, courtesy of the New York Times.

After moving from the environment of the South to the northern states, African Americans were inspired to be creative in different ways. The Great Migration resulted in the Harlem Renaissance, which was also fueled by immigrants from the Caribbean, and the Chicago Black Renaissance.

The Great Migration had effects on music as well as other cultural subjects. Many blues singers migrated from the Mississippi Delta to Chicago to escape racial discrimination. Muddy Waters, Chester Burnett, and Buddy Guy were among the most well-known blues artists who migrated to Chicago. Great Delta-born pianist Eddie Boyd told Living Blues magazine, “I thought of coming to Chicago where I could get away from some of that racism and where I would have an opportunity to, well, do something with my talent… It wasn’t peaches and cream, man, but it was a hell of a lot better than down there where I was born.”

The Great Migration drained off much of the rural Black population of the South and, for a time, froze or reduced African-American population growth in parts of the region. The migration changed the demographics in several states; there were decades of Black population decline, especially across the Deep South “black belt,” where cotton had been the main cash crop but had been devastated by the arrival of the boll weevil.

Factory Worker.

Educated African Americans were better able to obtain jobs after the Great Migration, eventually gaining a measure of class mobility, but the migrants encountered significant forms of discrimination. Because so many people migrated quickly, the African-American migrants were often resented by the urban European-American working class; fearing their ability to negotiate pay rates or secure employment, the ethnic whites felt threatened by the influx of new labor competition.

After the Civil Rights Movement, with the growth of jobs in the “New South,” its lower cost of living, family and kinship ties, and lessening discrimination at the hands of white people, the trend reversed, with more African Americans moving to the South, but far more slowly.

But by the end of the Great Migration, just over half of the African American population lived in the South, while a little less than half lived in the North and West. By that time, the African-American population had become highly urbanized. In 1900, only one-fifth of African Americans in the South were living in urban areas. By 1960, half of the African Americans in the South lived in urban areas, and by 1970, more than 80% of African Americans nationwide lived in cities.

About 1.1 million moved from the South in the 1950s, and another 2.4 million people in the 1960s and early 1970s. By the late 1970s, as deindustrialization and the Rust Belt crisis took hold, the Great Migration ended. But, in a reflection of changing economics, as well as the end of Jim Crow laws in the 1960s and improving race relations in the South, in the 1980s and early 1990s, more Black Americans were heading South than leaving that region.

In total, from 1916 to 1970, during this Great Migration, it is estimated that some six million black Southerners relocated to urban areas in the North and West.

The Great Migration was one of the largest and most rapid mass internal movements in history — perhaps the greatest not caused by the immediate threat of execution or starvation. In sheer numbers, it outranks the migration of any other ethnic group — Italians, Irish, Jews, or Poles — to the United States. For Black people, the migration meant leaving what had always been their economic and social base in America and finding a new one.

— Nicholas Lemann, American writer and academic, 1991

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024

Help Wanted at Long Island Shipyard.

Also See:

African American History in the U.S.

Lynchings & Hangings in America

Sources: