Hermann, Missouri – Little Germany – Legends of America (original) (raw)

1st Street in Hermann, Missouri, by Kathy Alexander.

Hermann, Missouri, the county seat of Gasconade County, evolved out of an effort to preserve German culture and traditions in America.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1920

In the early 19th century, several waves of German immigrants came to America and settled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dismayed at how quickly their countrymen were being assimilated into American society, many of the Philadelphia Germans dreamed of building a new city in the “Far West” that could and would be “German in every particular.”

In an effort to protect German traditions and heritage, the German Settlement Society was created in 1836. The society had almost utopian goals of a new community that could perpetuate traditional German culture and establish a self-supporting colony built around farming, commerce, and industry.

The Society soon sent several scouts into America’s heartland to search for land to create their new settlement. One of these scouts, George Bayer, a Philadelphia schoolteacher representing the Society, purchased 11,300 acres of land near the confluence of the Gasconade and Missouri Rivers. The steep, rugged terrain reminded him of the Rhine Valley in Germany, even though the beautiful area was perhaps not the most practical site for a town.

His descriptions of the area generated great enthusiasm among potential settlers back in Philadelphia. A town named Hermann, named for a German national hero, was platted by the Society before they even saw the land. On paper, Hermann was flat, with spacious market squares and sweeping boulevards. Thinking big, they made their city’s main street 10 feet wider than Philadelphia’s.

This area outside of Hermann, Missouri, does not reflect the steep hills and rugged terrain that the early pioneers faced in the immediate vicinity of Hermann. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

Soon, 17 settlers from Philadelphia started traveling westward to create their new community. When they stepped off the steamboat in December 1837, they discovered what one settler described as a “howling wilderness.” The land that Bayer purchased was located along steep bluffs overlooking the Missouri River, and the area’s rocky soil appeared to be totally inhospitable to agriculture. Their idealism died quickly, and some were very angry to discover that the Hermann lots they had purchased back in Philadelphia were what today’s residents jokingly refer to as “vertical acreage.”

The emigrants who came to Hermann quickly realized that they needed to find viable alternatives to traditional grain agriculture if their community was to prosper. Most of the land in the area is hilly and is covered with dense forests, generally limiting the size of farms to less than 120 acres. Fortunately, the land was fertile enough to support limited grain farming and livestock ranching, creating an agricultural base for the local economy. A unique natural feature that Hermann’s settlers noticed was an abundance of wild grapevines growing along the rocky hillsides. Local soils were ideal for grape cultivation, and viticulture quickly became a key element of the local economy.

In addition to the farmers, tradesmen, artisans, businessmen, and professionals were also involved in the early settlement and formation of Hermann. Within a short time, streets were laid out, solid houses were constructed, and shops and businesses were established. Within two years, the Settlement Society had dissolved, and George Bayer had passed away. However, Hermann survived its rocky start, and by 1839, its population had grown to 450 residents.

Paddlewheel steamboat on the Missouri River.

The new town also grew as a steamboat port along the Missouri River, which was the primary transportation resource in Missouri during the early decades of the 19th century, and most emigrants who came to Hermann did so via the river. During these days, the town sported a tavern on every corner and the largest general store between St. Louis and Kansas City.

In 1842, Hermann became the county seat of Gasconade County. When the county was first organized in 1821, it was situated at Gasconade City along the Gasconade River. It then moved several times due to flooding, so no permanent courthouse was built. In 1842, county voters decided to move the seat of government to Hermann to make sure it was out of the flood plain. Local residents contributed approximately $3,000 to build a square, two-story brick building located in the center of a city block along East Front Street. The courthouse sat atop a bluff overlooking the Missouri River, and its natural vistas added to the community’s aesthetics. Hermann gained prominence by acquiring the county seat and ensured its continued success and growth.

Stone Hill Winery in Hermann, Missouri in 1888.

Within no time, area farmers developed new varieties of grapes well-suited to Missouri soils, and in 1847, Michael Poeschel opened Hermann’s first commercial winery on a hill overlooking the town. This winery would later become the Stone Hill Winery that still exists today.

In the fall of 1848, Hermann held its first Weinfest, bringing people from St. Louis to the city on steamboats, where they enjoyed more than their share of sweet Catawba wine and marveled at the grapevine-covered hills. The Weinfest tradition continues in today’s Maifest and Octoberfest celebrations.

German wines, beer, ale, and liquor in 1871 by L.N. Rosenthal.

The quality of Hermann wines improved dramatically in the mid-1800s, largely thanks to the work of George Husmann, whose father had purchased a Hermann lot while the family was still living in Germany. A self-taught scientist, Husmann studied soil types and crossed wild and cultivated grapes to create hybrids that could withstand Missouri’s hot, humid summers and freezing winters.

In the latter half of the 19th century, railroads replaced steamboats as the primary means of transportation. Hermann became a station point along the Missouri Pacific Railroad between St. Louis and Jefferson City in 1854. This allowed Hermann to maintain its regional prominence as an agricultural shipping point and commercial center. Train transportation and access to outside markets also allowed for creating several light industrial plants within Hermann, most notably a shoe facility operated by the Florsheim Company.

Hermann, Missouri Wine Vault

By 1860, approximately 30 steamboats were based in Hermann. These boats transported raw goods, such as lumber from surrounding forests, iron from the Meramec region, and barrels of wine and beer, downriver to St. Louis. The steamboats also contributed to the growth of Hermann’s early tourism industry by bringing visitors into the city. At this time, the town was called home to about 1,100 people.

In the early 1870s, Hermann residents began to celebrate Maifest, a traditional German celebration of the arrival of spring. After the German school was built, early Maifests were last-day-of-school picnics for children, and after Sunday church, a bigger festivity was planned, including a parade to the city park, food, treats, and an afternoon of games. Many years later, it would grow into a city-wide celebration.

The Carl Strehly House in Hermann, Missouri, was built in 1842 and enlarged over the years.

Economic diversity in the city provided stability and allowed Hermann to maintain its German heritage. Local presses produced several German-language newspapers, including one that was published in the Carl Strehly House, that is now part of the Deutschheim State Historic Site. Many residents spoke German well into the 20th century.

By the turn of the century, Hermann’s winemakers had become wildly successful. Stone Hill Winery had grown to be the second-largest winery in the country and was winning gold medals at World’s Fair competitions around the globe. By this time, the town’s numerous vintners were producing an incredible three million gallons of wine a year. By 1904, 20 wineries operated in the Hermann vicinity, and Poeschel’s facility had grown to become the third-largest winery in the world.

Hermann fell on hard times during World War I, especially as the city suffered from anti-German sentiment provoked by the war. Making matters worse was the enactment of Prohibition in 1919, which sent the city reeling into the Great Depression a full decade before the rest of the country. Fortunately, economic diversity and community strength allowed the town to survive these challenges and remain a prosperous community as Missouri entered the 1920s. A side benefit also occurred as there was simply no money to modernize old buildings, which is one of the reasons so many continue to stand today.

Hermann, Missouri, in 1906.

In the 1920s, Missouri was just beginning to start building modern highways. In 1921, the State of Missouri passed the Centennial Road Law, which created a highway commission to coordinate the construction of a statewide road system linking Missouri’s county seats. A key component of Missouri’s emerging statewide highway system was the construction of bridges across major rivers. Government leaders in Hermann soon started to lobby for a bridge across the Missouri River connecting Hermann to U.S. Highway 40 north of the river and U.S. Highway 50 south of the river. Both highways were cross-state thoroughfares, joining St. Louis to Kansas City, and Highway 40 was part of a national road that reached back to the east coast. By linking the city to these two critical highways, Hermann could draw more tourists to its annual festivals and encourage the further growth of local industries and agribusinesses.

1928 bridge over the Missouri River in Hermann, Missouri, by the Historic American Building Survey.

The business leaders were finally successful, and the National Toll Bridge Company began to build the bridge in the fall of 1928. After a few delays, the bridge finally opened on the morning of August 29, 1930. Initial tolls ranged from 60¢ to $1.25. The new bridge was seen by many as a boon that would improve the local economy and transform Hermann into a commercial and tourist center. However, with the oncoming Great Depression, the bridge did not create dramatic economic or population growth.

Further, the bridge didn’t turn a profit for the National Toll Bridge Company, and it was sold to the Missouri State Highway Commission in 1932. The cantilevered truss bridge continued to carry traffic for decades before it closed in July 2007 and was replaced by a new bridge. The 401-foot-long bridge was demolished in 2008.

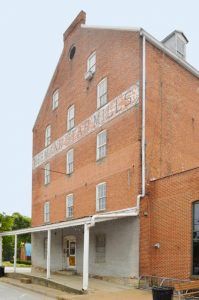

Star Mill in Hermann, Missouri by Kathy Alexander.

After Prohibition ended in 1933, some small operators in the area began producing wine again, but significant production wouldn’t be renewed for several decades.

In 1952, Hermann’s Maifest tradition grew into a citywide celebration when the Brush & Palette Club advertised the first public Maifest to raise funds for the restoration of the Rotunda Building, an unusual eight-sided structure in the city park that had fallen into disrepair. The outcome was almost too successful. A crowd of more than 40,000 descended on an unsuspecting Hermann. Traffic was a nightmare, food was sold out for a 50-mile radius, and restroom facilities were better not mentioned. The next year, the women of Hermann cooked for a week to prepare for the crowds. The event was a success, and a new tradition was born.

In the 1960s, people began rebuilding the Hermann area’s wine industry, which soon became one of the main tourist attractions. Today, the city of about 2,400 people is the commercial center of the Hermann American Viticultural Area, with the seven wineries in and around Hermann accounting for more than a third of the state’s total wine production. This includes Stone Hill Winery, the largest winemaking business in the state, and Hermannhof Winery, which are located within the city. Two miles south of Hermann off Missouri Highway 100 West is Adam Puchta Winery, the oldest continuously family-owned winery in the nation, under direct family ownership since 1855.

Concert Hall in Hermann, Missouri, by Kathy Alexander.

Hermann’s Old-World charm attracts visitors searching for the quiet pleasures of an earlier era. There are numerous historic buildings in Hermann. An area of five blocks from the Missouri River to Fifth Street is designated as a national historic district with several buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The district encompasses 360 contributing buildings that were established between 1838 and 1910.

The earliest of these buildings can be toured at the Deutschheim State Historic Site located at 109 West Second Street. This site includes the 1848 Potnmer-Gentner House and the 1845 Strehly House. Period furniture, tools, and gardens give visitors a glimpse into life in early Hermann.

Other interesting buildings include the 1906 Hermann City Hall, the 1877 Concert Hall, the 1871 German School, the 1896 Gasconade County Courthouse, and many others.

Hermann’s Maifest is held during the third weekend in May and an Oktoberfest is held on the first four weekends in October.

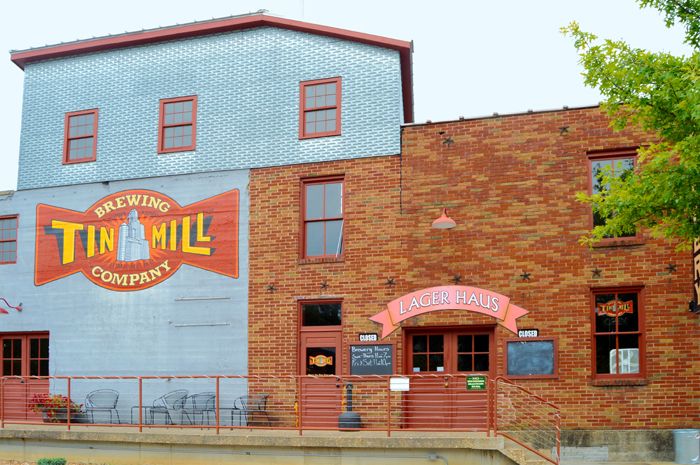

Tin Mill Brewery in Hermann, Missouri by Kathy Alexander.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Sources:

Gasconade County Historical Society

Hermann, Missouri

Library of Congress

Visit Hermann

Wikipedia