The Ho-Chunk or Winnebago of Wisconsin – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Naw-kaw, a Ho-Chunk chief, I.T. Bowen Lithographic,1836

The Ho-Chunk, also known as Hoocaagra or Winnebago, are a Siouan-speaking Native American people whose historic territory included parts of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and Illinois. They were closely related to the Chiwere people, which included the Ioway, Otoe, and Missouri tribes. The term “Winnebago” was used by the Potawatomi tribe, which meant “people of the dirty water”, referring to Wisconsin’s Fox River and Lake Winnebago, which were fouled by the bodies of dead fish in the summer. But they always called themselves Ho-Chaank, meaning “sacred voice.” Though they spoke a Sioux language, their culture was similar to the Algonquian peoples.

The oral traditions of the tribe state that the Ho-chunk originated at the Red Banks on Green Bay. Other tribal traditions relate how tribes such as the Quapaw, Missouri, Iowa, Oto, Omaha, and Ponca were once part of the Ho-chunk, but these other tribes continued to move farther west while the Ho-chunk stayed in Wisconsin.

Before Europeans ventured into the Ho-Chunk territory, the people were living in the Lake Winnebago area, building substantial rectangular houses. From here, they hunted, farmed, and gathered food, including nuts, berries, roots, and edible leaves. They often made forays out to other parts of their territory for hunting and gathering purposes. The tribe made up of 12 different clans, with each associated with a different animal spirit.

The main roles of the men of the tribe included being a hunter, fisherman, warrior when needed, and leaders involved in political relations with other tribes. Some men also created jewelry and other body decorations out of silver and copper. The men also were responsible for acquiring protection and powers from specific spirits, which was obtained by making offerings such as tobacco and war-bundles. To become men, boys would go through a rite of passage at puberty that involved fasting and acquiring a guardian spirit.

Winnebago Women about 1870. Touch of color by LOA.

Women were responsible for growing, gathering, and preserving food. They cultivated corn, beans, and squash, tapped maple trees for sap for syrup and candy, and collected berries, roots, and wild rice. They learned to recognize and use a wide range of roots and leaves for medicinal and herbal purposes. From the game their men brought back to camp, they tanned the hides to make clothing, storage bags, and coverings for dwellings. They were also responsible for the caring of children and elders.

Their clothing was comprised of fringed buckskin, which they frequently decorated with beautiful designs created from porcupine quills, feathers, and beads – a skill for which they are still renowned today. Body tattooing was common to both sexes.

In the mid-16th century, the influx of Ojibwa peoples in the northern portion of their range caused the Ho-Chunk to move to the south of their territory. Here, they were at odds some with the Illinois Indians.

The Ho-Chunk’s first contact with Europeans was when they met French explorer Jean Nicolet in 1634. At that time, they were living in the area around Green Bay of Lake Michigan in Wisconsin, reaching beyond Lake Winnebago to the Wisconsin River and to the Rock River in Illinois. It is estimated that their population was as much as 20,000.

Afterward, French trappers and traders began to come into their area, who described them as powerful and skilled warriors who frequently made war with other tribes. By the 1650s, the Ho-Chunk population was reduced to about 600 due to disease and war. They lost their dominance in the region when numerous Algonquian tribes migrated west to escape the powerful Iroquois tribes’ aggressiveness. When peace was established between the French and Iroquois in 1701, many of the Algonquian peoples returned to their homelands to the east, and the Ho-Chunk were relieved of the pressure on their territory.

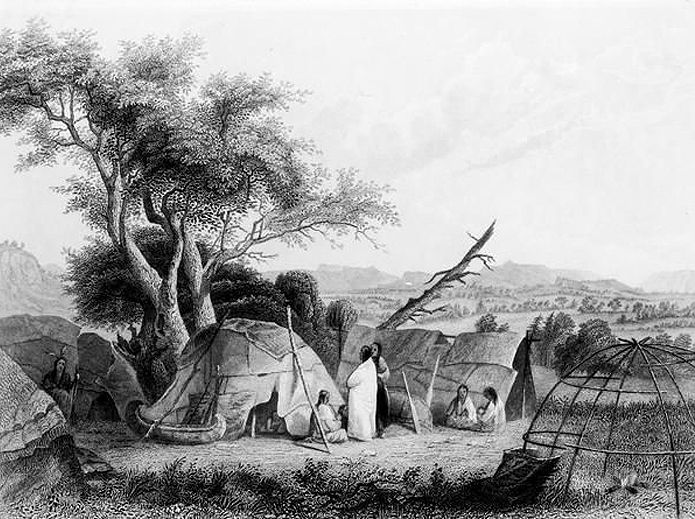

Ho-Chunk Wigwam

After 1741, while some remained in the Green Bay area, most returned inland. The population of the people gradually recovered, aided by intermarriage with neighboring tribes and with some of the French traders and trappers. They borrowed a number of Algonquian customs and traditions and entered into the fur trade. They continued to have gardens but relied more and more on hunting and trapping. Instead of the large villages they had previously lived in, they created smaller settlements that were dispersed over a wider area and began to live in domed wigwams. Increasingly, trading centers at Portage and Prairie du Chien drew them away from their earlier territory in the Green Bay region.

When Wisconsin became part of the United States in 1783, the Ho-chunk-like other Wisconsin tribes retained a strong attachment to the British and fought against the United States during the American Revolution.

By 1806, their population had recovered to about 2900. At about this same time, the Ho-Chunk began to follow the religious teachings of Shawnee Prophet Tenskwatawa and his brother Tecumseh. These Shawnee Indians from Ohio urged Indians to reject European American ways, such as drinking liquor, European-style clothing, and firearms. He also called for the tribes to refrain from ceding any more lands to the United States. In the War of 1812, the Ho-Chunk fought alongside the British and though they lost, the Ho-chunk retained their dislike for the United States.

Branching Horns, Ho-Chunk Warrior by Henry H, Bennett, 1905

By treaties made in 1825 and 1832, they ceded all of their lands south of the Wisconsin and Fox Rivers to the United States Government in return for a reservation on the west side of the Mississippi River above the upper Iowa River. In 1836 they suffered severely from smallpox. In 1837 they relinquished the title to their old country east of the Mississippi River, and in 1840 they removed to Iowa. Many, however, remained in their old lands.

In 1846, their population had reached 4,400 and they surrendered their reservation for one in Minnesota north of the Minnesota River. Afterward, their population dropped again to about 2,500 in 1848, at which time they were removed to Long Prairie Reservation, bounded by Crow Wing, Watab, Mississippi, and Long Prairie Reservations in Minnesota. In 1853 they removed to Crow River and in 1856 to Blue Earth, Minnesota, where they remained until the Dakota outbreak of 1862 when the white settlers in the area demanded their removal. In consequence, they were taken to Crow Creek Reservation in South Dakota but suffered so much from sickness, and in other ways, that they escaped to the Omaha for protection. There, a new reservation was assigned to them on the Omaha lands, where they were later allotted lands in severalty. Some, however, remained in Minnesota when the tribe was removed from that state and a larger number never left Wisconsin.

Today the two separate federally recognized related Native tribes are the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin and Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska. Their numbers today are estimated at more than 7,500 members of the Ho-Chunk Nation and more than 4,500 belonging to the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska.

©Kathy Weiser-Alexander, updated April 2021.

Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, courtesy Wikipedia

Also See:

Native American Photo Galleries

Native Americans – First Owners of America

Sources: