Coal Mining Towns Along Route 66 – Legends of America (original) (raw)

After leaving Wilmington, Illinois, on the Mother Road, you enter what was once a profitable coal-mining country, where small towns and large coal mines dotted the area. The first stop along this stretch of Route 66 is Braidwood, a town founded in 1865 when a rich vein of coal was discovered quite by accident.

Braidwood, Illinois

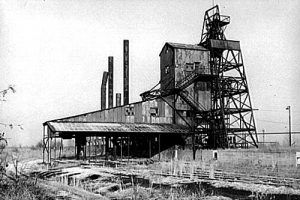

Illinois Coal Mine, 1939. Courtesy Library of Congress.

In 1865 William Henneberry was digging a water well on the Thomas Byron farm when he found, instead, rich black coal, and the boom was on. Named for James Braidwood, who sank the first deep coal mining shaft near Wilmington in 1872, the settlement was called home to some 2,000 people by 1873.

In the beginning, Braidwood was a wild and wooly town filled with immigrants from all over the world and their varying political, religious, and cultural ideals. These differences often spawned violence in the new and crusty town.

One such occasion occurred in April of 1876 when elections were being held for town officers, and a fight broke out just before the polls closed. When Marshall Simms entered the crowd and arrested one of the ringleaders, Pat Creeley, the mob went wild. When the crowd wrestled Simms to the ground, the marshal drew his revolver, meaning to use it as a club. Someone in the crowd grabbed it from him, and Creeley was released. Fortunately, Marshal Simms was unharmed. The crowd grew wilder, and several innocent bystanders were attacked and beaten. Next, the rioters attacked the polls, stealing the whole election record and beating the ballot counter senselessly. No arrests were ever made for this outrageous event.

Braidwood Teamsters

By the next year, the country was in the throes of a depression, and the coal miners were asked to take a cut in pay, which they accepted in the winter, but when another cut was imminent in the summer of 1877, the miners went on strike. The coal mining companies soon brought in strikebreakers from other localities and, after a month, transported blacks from the impoverished south by train carloads. Soon, the black strikebreakers were referred to as “blacklegs.”

On a Sunday in July, several black miners were walking in a line when they were verbally abused with a litany of offensive language from white coal miners and their wives. By the end of the month, the striking miners formed groups with plans to kill the strikebreakers, especially the “blacklegs.” Though the mining companies assured them protection, most African-American miners fled. Local officials requested help from the governor, who soon sent 1,300 soldiers to restore order, 200 of which stayed within Braidwood for several weeks.

Eventually, the strike was broken, and some black miners returned to work and stayed in the area to raise their families.

However, Braidwood still retained its reputation as a wild town full of transients, tramps, and thieves. The good citizens of the town locked their doors at night in fear of being robbed. Women were never seen on the street after the sun went down, and people never told anyone when they might be gone for several days for fear their valuables would be missing when they returned home. This atmosphere of fear finally led to the accidental shooting of the town marshal by the local Catholic Priest on Sunday, November 19, 1878.

Father McGuire had been so ill that he did not even conduct mass on that fateful day. His best friend, Marshal Muldowney, had spent most of the day with the priest, then left around 6:00 pm. Shortly, Father McGuire went upstairs and retired. Between 8 and 9 p.m., the marshal returned to lock the door and put out the lights.

Father McGuire was awakened by the noise and imagined the time near midnight. When the priest called out and got no response, he fired four shots from a revolver and shot Muldowney as he reached the top of the stairs.

The housekeeper came immediately and found the priest embracing the wounded man, who had been shot twice, once in the shoulder and once in the abdomen. Marshal Muldowney hung on for almost a week before he died, and Father McGuire was tried for murder. However, with the testimony of the housekeeper and Muldowney’s own son, combined with the fearful environment of the town, the jury deliberated for only an hour before returning a verdict of justifiable homicide.

On April 22, 1879, Braidwood experienced another tragedy: a terrible fire raged through the town. In less than an hour, more than a dozen buildings were destroyed by the inferno, including the grain elevator, the railroad depot, a warehouse, a gristmill, a hotel, two saloons, a blacksmith shop, and several homes.

But the town persevered, was rebuilt, and continued to draw newcomers to the area, one of which was a man named Peter Rossi from Italy. Arriving in the late 1870s, Rossi began manufacturing macaroni and in 1898, purchased the old Broadbent Hotel, which housed a full-fledged factory.

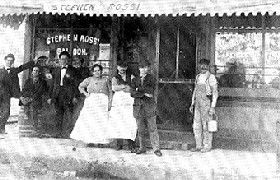

Rossi’s Saloon operated from 1912-1919, selling beer for a nickel a pail until Prohibition put it out of business. For the steady customers, there was a free spaghetti lunch in the back of the saloon.

Soon, he would move on to operate a bakery just off Division Street, and his son Stephen opened the Stephen Rossi Saloon in 1912, selling beer for a nickel a pail. The successful saloon would have continued on, but prohibition put it out of business in 1919.

When Route 66 ran through town, the Rossi family saw an opportunity and built a grocery store, service station, restaurant, and motor courts right alongside the Mother Road. In 1927 they erected a dance hall that did a thriving business until it was destroyed by fire in 1935.

Today Braidwood, with just a little more than 5,000 people, still provides a nostalgic glimpse of the vintage Mother Road with icons such as the Polk-A-Dot Drive-In. First started in 1956 in a school bus painted with rainbow-colored polka-dots; lunch was served from a mini-sized kitchen inside the bus. Today this great drive-in at 222 N. Front Street sports bigger-than-life statues of James Dean, Elvis, and the Blues Brothers, along with great food. Several years ago, there was also a statue of Marilyn Monroe, but she is gone today.

The Polk-A-Dot Drive-In in Braidwood, Illinois, Kathy Alexander.

When the Polk-A-Dot Drive-In still featured Marilyn Monroe, Kathy Alexander.

Braceville, Illinois

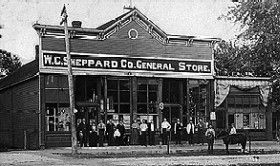

W.C. Sheppard’s was one of two grocery and dry goods stores operated in Braceville. The store was located on Mitchell Street.

The village of Braceville was actually once a thriving city with 3,500 residents at its height in the 1870s. By the late 1880s, the town sported six general merchandise stores, two banks, a hotel, two restaurants, and 18 other retail businesses.

Braceville thrived until the summer of 1910, when the miners of the Braceville Coal Company went on strike. Fed up with the whole affair, the coal company simply closed and within just a few months, the town was abandoned, leaving behind an opera house, a large frame school, and many empty businesses. Of these today, there is no sign other than a few slag heaps along the old highway. However, the Braceville area still supports some 800 residents. Braceville is home to Mazonia/Braidwood Fish & Wildlife Area, which features quality sport fishing lakes stocked with largemouth and smallmouth bass, bluegill, sunfish, crappie, channel catfish, and bullhead, as well as areas for waterfowl hunting.

Gardner, Illinois

The Riviera Roadhouse in Gardner, IL, 2004. Destroyed by Fire in 2010.

The next town on this coal mining ride is Gardner. Right after crossing the Mazon River, two miles before reaching the small town of Gardner is the location of the once popular Riviera Restaurant. The historic roadhouse, sadly, burned down in June 2010. This historic Roadhouse was built in 1928 when a South Wilmington businessman named James Girot moved the buildings from both Gardner and South Wilmington to form the structure. Reportedly, movie legends Gene Kelly and Tom Mix regularly stopped here, and it was a favorite out-of-the-way joint for Al Capone during his heydays. During Prohibition, the old roadhouse offered liquor and slot machines to discrete travelers. Perhaps the booze was even provided by the infamous bootlegger Al Capone.

Behind the Riviera once stood an old horse-drawn Streetcar Diner over 100 years old. In 1932 George Kaldem purchased the streetcar and moved it to Gardner. Soon it became a simple diner providing good food with just a small sign in front to identify it. It became an unofficial stop on the Greyhound bus line for a while before the diner closed in 1939. In 1955 Gordon Gunderson, James Girot’s son-in-law, purchased the streetcar and moved it to its present location behind the Riviera. The Riviera mostly used the streetcar diner as a storage space until the Illinois Route 66 Preservation Committee discovered it and restored it to its original Route 66 appearance.

Thankfully, the Streetcar Diner was spared from the fire that took the roadhouse. It has since been moved into Gardner.

Keep on kickin’ asphalt as you head down the Mother road to the small towns of Dwight, Odell, and Pontiac, and as always, enjoy the ride!

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

This art deco ceramic tile station is still doing business as Kelly Tires in Braidwood, Illinois, Kathy Weiser-Alexander, October, 2010. Click for prints & products.

Gardner, Illinois quaint downtown area, Kathy Weiser-Alexander, October, 2010.