Immigration – The First Gateway – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Ellis Island, Jersey City, New Jersey.

For the thousands of people who immigrated to America, an emotional gateway had to be passed. In New York City, New York, Ellis Island was the first entry point for most immigrants, the first stop on their way to new opportunities and experiences in America. For most immigrants, Ellis Island was an “Island of Hope.” Still, for others, it became the “Island of Tears” – a place where families were separated and individuals were denied entry into the United States.

Between 1820 and 1920, it is estimated that over 34,000,000 people left their native lands, primarily in Europe, to build new lives in America. Many of them would travel quickly past the crowded cities of the East to reach the freedom and opportunities of the American West. But who were these immigrants, and why did they settle in the American West?

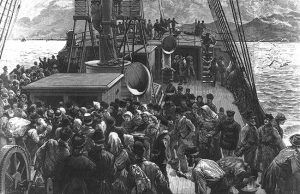

German Immigrants heading to New York.

The immigrants represented diverse European backgrounds. The earliest arrivals included people from England, Ireland, and Germany. This first wave of new Americans left their homelands from 1820 to 1840, many seeking new lives after the Napoleonic Wars. In 1845, Ireland suffered the first of several disastrous potato famines. Thousands died at home, while over 1,500,000 migrated to escape starvation. Germans also came to America, leaving behind brutal political suppression after the 1848 revolution and seeking economic opportunities. These groups brought the number of immigrants to over three million in less than 20 years.

After the American Civil War, the “new” immigrants from Italy, Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Poland came for various reasons. The Industrial Revolution had a significant impact on their lives. In Europe, competition with large manufacturers put many craftsmen out of work. It also gave many agricultural groups a reason to leave the farm in the “old country” for new land or city jobs in America. Early arrivals settled in the large eastern cities of the United States to seek greater job opportunities.

Italian Immigrants in New York by William A. Rogers, 1890.

As these cities grew, so did the population of the lower and middle classes. Many people felt the same pressures they had experienced back in Europe, such as overcrowding and lessening freedom of speech, religion, and politics. Land speculators used these emotions to advertise the West as “the land of milk and honey” and “The Garden of Eden” of America, full of opportunity and promise. Promoters worked in Europe and the United States. Some were agents for the steamship and immigration companies or land grant railroads. Others worked for Western real estate businesses or the state and territorial immigration offices. Newspaper and guidebook authors and European travelers who returned to their homelands helped promote the American West. Many used misleading sales techniques, including outright lies and false advertising, to increase profits for themselves and their companies. Nevertheless, immigrants yearning to make a new start averaged 400,000 annually by the 1850s.

Immigrant Ship.

Their journeys were full of sacrifice, danger, and hardship. Most knew they would never see their friends, family, or homeland again. Preparations began with applying the proper paperwork, selling personal belongings or real estate to finance the trip, and packing all possessions into makeshift bundles and boxes. If the emigrant lived inland, transportation to the coast had to be arranged by rail, wagon, carriage, boat, or on foot. Upon reaching a port town, the emigrants had to go through thieves and corrupt businessmen who tried to cheat them at the docks.

The next step, the ocean voyage, was one of the most hazardous parts of the trip. In the age of wooden sailing vessels, a passage of the Atlantic could take two to three months. Living conditions on board were terrible, especially in steerage, where most immigrants traveled. Many died during the passage, with high mortality rates among the old and young. Diseases such as typhus, cholera, and dysentery were rampant. Shipwrecks, storms at sea, and severe seasickness also plagued travelers. The most critical factor in improving these conditions was the introduction of the steamship. By the 1870s, the average duration of an Atlantic voyage had been cut to two weeks.

Welcome to New York.

There were several American ports of entry, but New York City was the busiest, especially after the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825. When a ship carrying immigrants arrived in New York Harbor in the early 1800s, a doctor rowed from a Quarantine office on Staten Island to inspect passengers for contagious diseases. If the ship passes inspection, the new citizens can move through customs to start a new life in America. Once again, unscrupulous runners and agents who worked for the railroad, steamboat, boarding house, and money exchange concerns were waiting at the exits. Armed thugs, who traveled with these company “representatives,” sometimes bullied immigrants into accompanying them and exploited the new arrivals, stealing their possessions.

As a result of these dangers and the filthy traveling conditions in steerage compartments on sailing vessels, New York State appointed a commission in 1847 to inspect ships and the onshore activities of known thieves and swindlers. In 1855, a new immigrant landing depot called Castle Garden was constructed in Battery Park on the southern tip of Manhattan to protect the new arrivals.

Castle Garden, New York

Castle Garden was originally built in 1811 as Castle Clinton, a Federal fort to guard New York and its harbor against British invasion. The fort was ceded to the city in 1823 and served as a concert hall and reception center for visiting dignitaries. By the early 1850s, Battery Park was being enlarged through landfill, and the city commissioners decided to locate a permanent immigration landing depot. Immigrants would now be brought directly to Castle Garden after passing through customs for assistance and directions.

One observer wrote in 1856 that after being registered by an immigration clerk, the new arrivals could “… enjoy themselves in the depot by taking their meals, cleansing themselves in the spacious bathrooms, or promenading on the galleries or the dock. The utmost order prevailed; all requisite information was given to passengers by officials conversing in different languages; letters from friends were transmitted to landing passengers, bringing them money or directions on how to proceed, etc.”

In a direct reference to the Western territories, the New York Herald of May 15, 1856, reported that “It is pleasant to learn that the immigrants who have lately arrived have been of a better class than usual. They have brought with them an average of $72 per head. Let them come, but keep out of politics for five years. There’s plenty of room out West yet.”

Gateway Arch, St. Louis, Missouri.

Once they left the Eastern cities, immigrants moved westward in various ways. By the 1830s, well-established trails and roads had been laid out in the East. If a person could afford not to walk, horses, wagons, and stages were a way to move westward. Water transportation, however, remained the most efficient and cheapest method. The Erie Canal was the preferred route; it began in New York City and was the easiest way to circumvent the Appalachian Mountains. Water and land transportation from Buffalo, New York, could take the traveler across Ohio to the Ohio River, where flatboats, keelboats, and the newer steamboats plied the waters. Settlers traveled down this river to Cairo, Illinois, and ascended the Mississippi River by steamboat to St. Louis, Missouri. Some settled there, while others pushed still further westward.

Even though the number of immigrants slowed somewhat during the Civil War, the tide swelled again during the 1870s and 80s, when as many as 14,000,000 people arrived. Some came in response to the free land offered in the Homestead Act of 1862. Others saw the chance to escape the confinement of social class or oppressive rulers in their homelands. The railroads that blanketed the West after the war allowed immigrants to travel quickly and faster to their destinations. The railroad companies also offered free land to encourage settlement in their service areas. For the Russians, Swedes, and Norwegians bound for Minnesota and Dakota, and the Germans and French headed for Kansas and Nebraska, America meant a farm of their own and a new life.

By the 1890s, the tide of immigrants had become too overwhelming to handle. In response to the unique needs of processing so many permanent newcomers, a particular immigration station was constructed in New York Harbor. Called Ellis Island, the station was built on what was primarily a man-made island and finished in 1892. A fire swept the buildings in 1897, and a new station was built by 1900. The station processed an average of 500,000 visitors annually, with the peak year of 1907 bringing 1,004,756. During the first 20 years of the 1900s, restrictions on immigration began to curtail the tide until, in 1924, the Immigration Act ended this significant era.

Ellis Island, used for various functions after its heyday, was abandoned by the Immigration Service in 1954. It was in extreme deterioration by 1965, when the National Park Service acquired it. Extensive restoration efforts between 1984 and 1990 have returned the site to its circa 1900 appearance. The restored immigrant station and extensive Museum of American Immigration on Ellis Island tell the visitor not just of the experiences of 20th-century immigrants but also of the epic journeys of all the people who left their native lands to settle in America. Immigrants followed through two gateways to reach new opportunities in the American West, the first in the eastern port cities and the second in St. Louis, Missouri.

Immigrants at Ellis Island, by Bain News Service.