The Powerful Iroquois Confederacy of the Northeast – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Iroquois by William Drennan, 1914

The Iroquois or Haudenosaunee were a powerful northeast Native American confederacy who lived primarily in Ontario, Canada, and upstate New York for over 4,000 years. Technically, “Iroquois” refers to a language rather than a particular tribe, but early on, it began to refer to a “nation” of Indians made up of five tribes, including the Seneca, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, and Mohawk.

Other tribes of Iroquoian stock not part of the Confederacy were the Huron, Tionontati, the Neutral Nation of Ontario; the Erie and Conestoga in Ohio and Pennsylvania; and the Meherrin, Nottoway, Tuscarora, and Cherokee, of Virginia and Carolina.

The name “Iroquois” is a French derivative of disputed origin and meaning but may come from the Algonquin word Irinakhow, meaning “real snakes.” The Algonquin tribes denoted hostile tribes as snakes. They called themselves Haudenosaunee, which means “people of the longhouse.”

After Europeans arrived, they were known during the colonial years to the French as the Iroquois League, later as the Iroquois Confederacy, and to the English as the Five Nations. After 1722, they accepted the Tuscarora people from the Southeast into their confederacy and became known as the Six Nations.

History varies as to when the Iroquois League was established. Some historians believe the tribes came together as early as 1142, while others contend it was formed in about 1450. According to oral histories, the tribes, who had been fighting, raiding, and feuding with one another and other tribes, were brought together through the efforts of two men and one woman. They were Dekanawida, sometimes known as the Great Peacemaker, Hiawatha, and Jigonhsasee, known as the Mother of Nations.

Seneca Chief Red jacket of the Iroquois league.

They subsequently created a highly egalitarian society and united to form a powerful nation. They designed an elaborate political system, which included a two-house legislature. The chiefs from the Seneca and Mohawk tribes met in one house, while the Oneida and Cayuga met in the other. The Onondaga broke ties and had the power to veto decisions made by the others. Early on, there was an unwritten constitution that described these proceedings. Such a complex political arrangement was unknown in Europe at that time. It might be compared to our own system of independent state and federal jurisdiction. In fact, the Iroquois recommended their system as a model at the outbreak of the American Revolution.

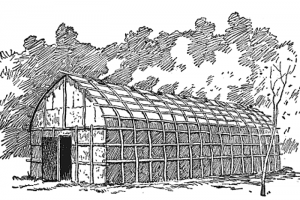

Iroquois Longhouse

The Iroquois lived in longhouses, some of which extended more than the length of a football field. However, most structures ranged from 50 to 100 feet in length and 15 to 20 feet in width. The interior was divided into equal size compartments, which opened on a central passageway. Each compartment sheltered one family so that as many as 20 families might live under one roof. At the ends of the building were separate rooms for storage and guest purposes. The occupants of the house were usually closely related by clan kinship. In the principal towns, the houses were compactly and regularly arranged and enclosed within strong palisades.

Surrounding the villages were extensive cornfields and orchards. The tribes also cultivated squash, beans, and tobacco, and the women gathered wild roots, greens, berries, and nuts. The men hunted for game and fished. Their early weapons were the bow, knife, stone and wooden clubs, and stone-headed lances. They used shields made of rawhide or wickerwork.

Iroquois Woman

Women held a unique role within the tribes, believed to be linked to the earth’s power to create life. The tribes were matrilineal, whereby families moved into the mother’s longhouse, and family lineage was traced from her.

Each tribe had a women’s council which took the initiative in all matters of public importance, including the nomination of members of the chief’s council, which was made up of both hereditary chiefs and additional members chosen for their abilities. Fifty hereditary chiefs from all five tribes constituted the league council, which ratified the nominations made by the women’s council.

No alien could become a member of the tribe except by formal adoption into a clan, which the women of the clan decided. The women decided the fate of captives for life or death. As the cultivators of the ground, women determined how the food would be distributed and held jurisdiction of the territorial domain. As mothers of the warriors, they decided on questions of war and peace.

In the summer, the people went mostly naked, with the men wearing only a decorated breechcloth with a belt worn around the waist. The primary item of women’s clothing was a skirt. In the winter, they wore fringed buckskins, leggings, moccasins, and a robe or blanket. Clothing was adorned with moose-hair embroidery, and decorated pouches for carrying personal items completed the costumes. The men carefully removed all facial hair and wore their hair in a Mohawk style. Tattoos were common for both sexes.

Unlike most eastern Indians, the Iroquois were monogamists, but divorce was easy and frequent. The children always remained with the mother.

Running the Gauntlet

The Iroquois were well known for their constant warfare, merciless treatment of prisoners of war, and their training of males to be immune to pain. They regularly practiced “Mourning War” raids to avenge warriors killed in a previous battle. These were conducted to provide an outlet for grief and mourning. The purpose was to abduct members of rival tribes as compensation. Upon their arrival back to camp, the captives were stripped, bound at the hands and feet, and forced to walk a gauntlet of tribe members who repeatedly struck them with clubs, torches, and knives. Occasionally, the clan’s matriarch demanded that these captives be immediately killed in vengeance. However, this was not normally the case.

The tribal council then assigned each prisoner to a family that had lost relatives. Women, children, and skilled or especially attractive men were adopted into the family. However, these adopted captives were never considered equal members of the Confederacy. Other captives, especially warriors, were condemned to die through ritual sacrifice. These men were tortured in a lengthy, highly ritualized ceremony until they died. Other tribes said the Iroquois concluded the ceremony by cooking and eating his remains.

Europeans first encountered the Iroquois in 1535 when French explorer Jacques Cartier sailed up the St. Lawrence River.

The French had established a presence in Canada for over 50 years before they next met the Iroquois. During that time, the Iroquois acquired European trade goods through raids on other Indian tribes. The Iroquois quickly found the metal tools far superior to their stone, bone, shell, and wood implements. At that time, woven cloth began to replace the animal skins usually used for clothing materials.

These recurring raids prompted the French to help their Indian allies attacked the Iroquois in 1609. At that time, Samuel de Champlain, a French trader, and explorer, was working to form better relations with the local native tribes, including the Huron and the Algonquin, who lived in the area of the St. Lawrence River. These tribes demanded that Champlain help them in their war against the Iroquois, who lived further south. In the summer of 1609, Champlain set off with nine French soldiers and 300 natives to explore the Richelieu River. After having no encounters with the Iroquois, many of the men headed back, leaving Champlain with only two Frenchmen and 60 natives.

Samuel de Champlain, French explorer and trader

On July 29, along the southern shores of Lake Champlain, New York, they came upon a group of Iroquois, and a battle began the next day. When 200 warriors of the tribe advanced on Champlain’s position, Champlain fired his long gun, killing two of them with a single shot, and one of his men killed the third. Having never seen the power of firearms, the Indians hastily retreated. They were followed by Champlain and his men, who killed 13 more warriors. This action set the tone for French-Iroquois relations, resulting in outright hostility for centuries. Afterward, the tribe made aggressive efforts to buy guns from Dutch traders.

More and more Europeans would then make their way to the area when the Confederacy was based in Ontario and Quebec, Canada, New York, and Pennsylvania in the United States. Though the Europeans provided the Indians with better tools, they were disastrous for the indigenous people. They brought diseases such as smallpox, measles, influenza, and lung infections, for which they had developed no immunity and knew no cures.

Beginning in 1610, the Dutch established a series of seasonal trading posts on the Hudson and Delaware Rivers, including one on Castle Island at the eastern edge of Mohawk territory near present-day Albany.

This removed the Iroquois’ need to rely on the French and their allied tribes to travel through their lands to reach European traders. It also offered the opportunity to trade valuable goods, such as firearms, iron tools, and blankets, in exchange for animal pelts. The tribes then began large-scale hunting for furs.

This soon led to stiff competition between the Iroquois and other neighboring tribes who supported the French. These included many of their traditional enemies, such as the Huron and Neutral Confederacies, Tionontati, Erie, and Susquehannock.

Fort Amsterdam was one of the many Dutch forts established in New York

By the 1630s, the Iroquois had become fully armed with European weaponry through their trade with the Dutch. Many of their warriors were expert gunmen, enabling them to start upon a career of conquest that made the Iroquois name a terror for a thousand miles.

By 1640, the beaver had largely disappeared from the Hudson Valley. The tribe, having become dependent upon the items they received in exchange for furs, began a campaign referred to as the Beaver Wars, in which they fought other tribes to expand the control of their lands and gain access to more fur-bearing game animals.

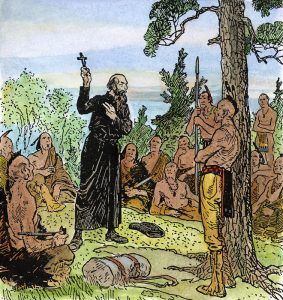

Jesuit Missionary

In 1642 the Jesuit missionary Jogues, while on his way to the Huron, was taken by a Mohawk war party and cruelly tortured until the Dutch rescued him. The same thing happened to Jesuit Bresani in 1644. In 1646, on the conclusion of an uneasy peace with the Iroquois, Father Jogues again offered himself for the Mohawk mission, but shortly after his arrival, was condemned and tortured to death on the charge of being the cause of a pestilence and a plague upon the crops.

Between 1648 and 1680, the Iroquois Confederacy drove out the Huron in 1649, the Shawnee, and Tionontati in 1650, the Neutral Nation in 1651, the Erie Tribe in 1657, the Conestoga in 1675, and the Susquehannock in 1680. Those who lived were incorporated into the Iroquois tribes. Considered one of the bloodiest conflicts in North America, these other tribes were pushed westward to the Mississippi River or southward into the Carolinas.

The conflict slowed when the Iroquois lost their Dutch allies after the English took over New York in 1664.

During the 17th century, the Iroquois acquired a fearsome reputation among the Europeans. It was the policy of the Six Nations to use this reputation to play off the French against the British to extract the maximum amount of material rewards. In 1689, the English Crown provided the Six Nations goods worth £100 in exchange for help against the French, and in 1693 the Iroquois received goods worth £600 from the English.

Iroquois in War

During King William’s War of 1689-1697, they were allied with the English and fought with them again during Queen Anne’s War from 1702 to 1713. During this war, arrangements were made for three Mohawk chiefs and a Mahican chief to travel to London in 1710 to meet with Queen Anne to seal an alliance with the British. Queen Anne was so impressed by her visitors that she commissioned their portraits by court painter. The portraits are believed to be the earliest surviving oil portraits of Aboriginal peoples taken from life.

The Iroquois Confederacy had a population of about 12,000 at its peak in 1700. By that time, they had subdued all the principal Indian nations in the territory now comprised of New York, Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, and parts of Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Northern Tennessee, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, New England, and southeast Canada.

After the 1701 peace treaty with the French, the Iroquois remained mostly neutral. However, the same year, they received £800 in goods from the British.

At this time, the French, Dutch and British colonists in New France (Canada) and what would become the Thirteen Colonies recognized a need to gain favor with the Iroquois.

Tuscarora Chief

In 1714, the Tuscarora of North Carolina, defeated by the colonists, joined the Iroquois Confederacy, which was afterward known as the Six Nations. However, the Tuscarora would achieve full political equality only after long years of probation as “infants,” “boys,” and “observers.”

The Iroquois chose to ally with the English, which became crucial during the French and Indian War, which began in 1754. The British and Iroquois fought the French and their Algonquin allies during the war. The Iroquois hoped that aiding the British would bring favors after the war. When the war was over in 1763, the British government used the Iroquois conquests as a claim to the old Northwest Territory. It issued a proclamation that restricted white settlement beyond the Appalachians. However, this was largely ignored by the settlers and local governments.

When the American Revolution began in 1775, the tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy divided, with the Oneida and the Tuscarora siding with the Americans and the Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, the Seneca remaining loyal to Great Britain. This marked the first significant split among the Six Nations.

Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant by Charles Willson Peale

After a series of successful operations against frontier settlements led by the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant and his British allies, the United States reacted with a vengeance. In 1779, George Washington ordered Colonel Daniel Brodhead and General John Sullivan to lead expeditions against the Iroquois nations to “not merely overrun, but destroy,” the British-Indian alliance. The campaign successfully ended the ability of the British and Iroquois to mount any further significant attacks on American settlements.

With the British defeated, the war ended in 1783. They gave up the Iroquois territory without consulting with the tribes, who were forced to relocate. At that time, most of the Iroquois moved to Canada, where they were given land by the British.

Those remaining in New York were required to live mostly on reservations.

By 1800, the Iroquois had been reduced to a population of just 4,000 due to wars and diseases.

The Iroquois population recovered by 1910 to about 8,000 in the United States, living in New York, Wisconsin, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania. Even more, were living in Canada.

Today, there are approximately 28,000 living in the United States and approximately 30,000 more in Canada. The Cayuga, Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca, and Tuscarora Nations are federally recognized in New York. The Oneida are also recognized in Wisconsin, and the Seneca-Cayuga Tribe is recognized in Oklahoma.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Iroquois Warriors

Also See:

Native American Photo Galleries

Native Americans – First Owners of America

Sources:

The Baldwin Project

Catholic Encyclopedia

New World Encyclopedia

U.S. History

Wikipedia