James B. Hume – California Lawman & Detective – Legends of America (original) (raw)

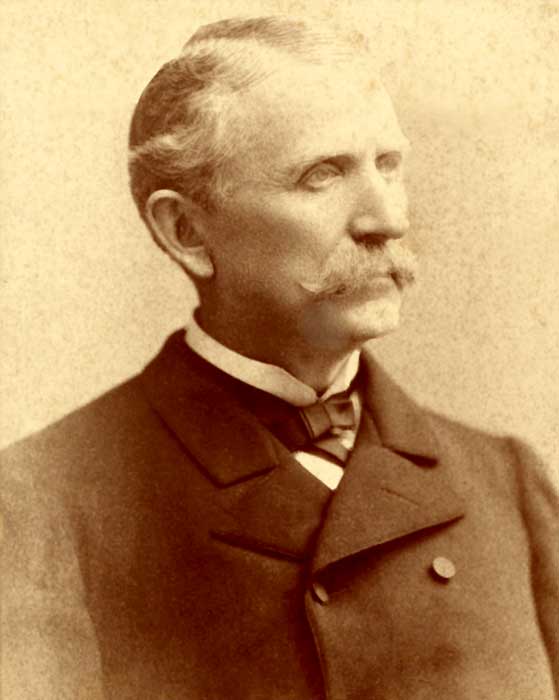

James B. Hume

James B. Hume was a miner, trader, and lawman in California after the Gold Rush began but left his mark on history as a Wells Fargo detective who captured stagecoach robbers such as Black Bart.

James Bunyon Hume was born in Delaware County, New York, to Scotch parents, Robert and Catherine Rose Hume, on January 23, 1827. The family moved to Indiana nine years later. James and his brother John left their home in 1850 to seek fortunes in the California goldfields. In addition to prospecting and gold panning, James also operated a trade store intermittently.

In 1860, he took a job as a deputy tax collector for El Dorado County, California. He began his career as a lawman In 1864 when he was appointed City Marshal of Placerville, California. The same year, he was hired as Undersheriff of El Dorado County. During this time, he helped to capture, kill, and scatter members of Ingram’s Rangers, a group of about 50 Confederate Bushwhackers. They committed the Bullion Bend Robbery and planned other raids before being broken up by the Union authorities.

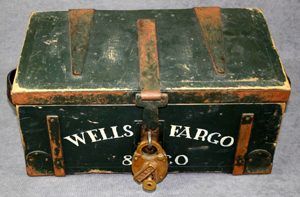

Wells Fargo Strongbox

In 1868, Hume ran for Sheriff and won, staying in office for two years. In 1871, Wells Fargo & Company hired him as a detective. However, the following year, the company gave him a leave to serve as deputy warden of the Nevada State Prison in Carson City. In 1871, 29 inmates severely injured the warden and escaped in September. Hume would serve in the prison for 11 months.

In 1873 James B. Hume became the Chief Special Officer of Wells Fargo & Company to protect gold, money, and other valuables that the stages carried. By this time, the company had built a reputation for taking safety seriously in transporting goods. To safeguard valuable shipments, gold and other treasure were contained in sturdy wooden boxes carried in the front boot of a stagecoach or secured inside the stagecoach in an iron safe.

Despite these precautions, outlaws found Wells Fargo’s treasure boxes too tempting to resist, and robbery attempts were common. The company also hired armed messengers to “ride shotgun” and sit up front with drivers to guard valuable shipments to reduce crime. To pursue criminals after a robbery occurred, the company also hired a small force of special agent investigators who helped build its reputation for security. Though it was very profitable, its losses due to robbery were steadily growing.

As head of this detective force in California, Nevada, and Utah, Hume was described as “one of the best detectives on the Pacific Coast; prompt, vigilant, and firm; always sober, reticent in his business affairs; knew no fear of danger; confided into the fullest extent of his employers, and generally esteemed by all who have the pleasure of his acquaintance.”

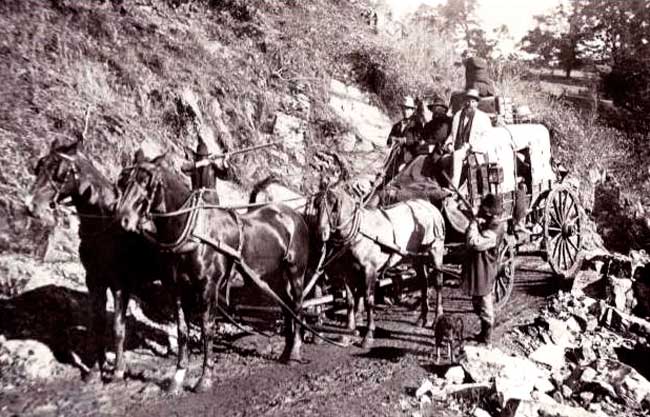

Stagecoach Robbery

Hume quickly began to build Wells Fargo’s investigative unit by getting personally acquainted with drivers and shotgun messengers, and he often changed stagecoach routes and schedules. He redesigned the treasure box, making it too difficult for a single person to handle. He also creatively used early science and ballistics to catch outlaws by matching buckshot and bullets to guns and taking footprints. The special agents pursued robbers themselves and often assisted local sheriffs and law enforcement officers. Though they held no arrest powers, they were trained to keep a keen eye for evidence and sharp investigative techniques and developed a reputation for dogged pursuit.

Hume kept a “mug book” of photos and descriptions of known bandits. After a robbery, Wells Fargo’s agent in the town nearest the crime scene reported the robbery to company management, organized law enforcement pursuit, and printed reward posters enlisting the aid of local citizens. A typical reward for the arrest and conviction of a robber was $250 plus one-quarter of any treasure recovered.

One of Hume’s most famous cases was that of Black Bart, a cunning and intelligent stagecoach robber. Hume, who had been trailing Black Bart almost from the beginning of the thief’s career, visited the sites of all the robberies and patiently put together a valuable list of information. Witnesses described the outlaw as a polite, friendly man in his fifties, who stood about five feet, 10 inches tall, with brownish-gray hair, and a gray mustache and matching goatee.

Hume’s major break occurred on November 3, 1883, when Bart robbed a Wells Fargo coach between Sonora to Milton, California. However, when one of the drivers fired a shot at the outlaw, he fled and dropped a handkerchief that bore a laundry mark. Hume then sent special detective Harry Morse, a former Alameda County sheriff, to visit every laundry in San Francisco to track down where the mark originated. Eventually, Morse tracked it down to the right laundry, and it was found to have been owned by C.E. Bolton, a man who lived in a hotel on Second Street. Bolton was none other than the thief, Black Bart, who confessed and was sent to prison at San Quentin.

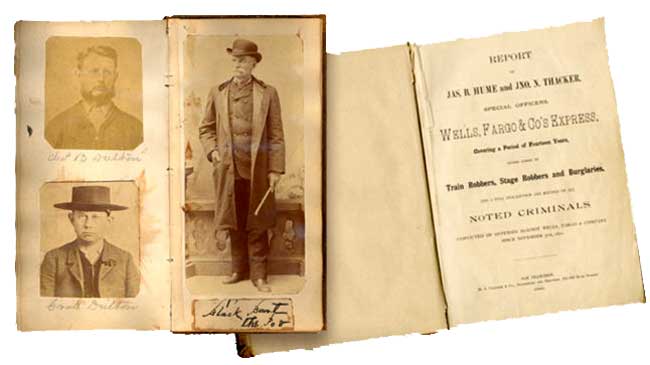

Robbers Record by James Hume and John N. Thacker

In 1885, Hume and John N. Thacker published a comprehensive report called the Robbers Record. They recorded details of 347 robberies and attempted robberies on Wells Fargo treasure shipments transported by stagecoach and train between 1870 and 1884. They also provided detailed descriptions of 205 convicted robbers to aid law enforcement officers.

Meanwhile, James married Lida Munson, the daughter of a prominent pioneer of El Dorado County, on April 28, 1884, and the couple would have one son, Samuel James Hume.

From 1870 to 1884, Wells Fargo spent more than a half-million dollars hiring special agents and detectives, paying rewards, and investing in other crime-prevention measures. The 512,414spentonsecurityandprotectionexceededthe512,414 spent on security and protection exceeded the 512,414spentonsecurityandprotectionexceededthe415,312 lost in robberies during those years. Relentless pursuit and systematic gathering of evidence by the company’s special agent force helped achieve a 70 percent conviction rate for stage and train bandits during these same years.

James Hume became known as “the Sherlock Holmes of the Wild West” and continued to work for Wells Fargo until his death in 1904. However, after an illness in 1897, he slowed down and began working fewer road trips. He died at his home at the age of 77 in Berkeley, California, on May 18, 1904.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

Wells Fargo Office, San Francisco, California

Also See:

Charles “Black Bart” Bowles – The Poet Outlaw

Tales of the Shotgun-Messenger Service, by Wyatt Earp

Wells Fargo – Staging & Banking in the Old West

Sources: