The Kingdom of Quivira, Kansas – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Cibola – Seven Cities of Gold

As early as 1530, the Spanish authorities in Mexico heard reports of the “Seven Cities of Cibola,” which were reputed to be exceedingly opulent. Still, it was not until ten years later that any systematic attempt was made to find them and exploit their wealth. The Coronado Expedition was sent out from New Spain for that purpose in 1540. In winter quarters near the present city of Albuquerque, New Mexico, Coronado learned from an Indian slave of a province teeming with wealth somewhere in the interior. This province subsequently became known as Quivira. There is some question about whether the name “Quivira” is of Indian origin. One historian suggests that the original name might have been “Quebira,” from the Arabic word “quebir” — meaning great — and that it was probably first used by the survivors of the Narvaez expedition who found their way to Mexico in the spring of 1536.

The province of Quivira was early on claimed by nearly every state in the Missouri Valley, and it was only in the late 19th Century that archaeologists gave it a definite location.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado

Acting upon the information received from the Indian, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado set out in April 1541 for the province, which he finally reached after wandering over the plains for more than two months. As the season began to wane, he returned to his quarters of the preceding winter, where on October 20, he wrote to the king of Spain a letter, in which he said:

“The province of Quivira is 950 leagues from Mexico. Where I reached it is in the 40th degree. The country itself is the best I have ever seen for producing all the products of Spain, for besides the land itself being very fat and black and being well watered by the rivulets and springs and rivers, I found prunes like those of Spain, and nuts, and very good sweet grapes and mulberries. I had been told that the houses were made of stone and were several storied; they are only of straw, and the inhabitants are as savage as any that I have seen.

They have no clothes, nor cotton to make them of; they simply tan the hides of the cows which they hunt and which pasture around their village and in the neighborhood of a large river. They eat their meat raw like the Querechos and Tejas and are enemies to one another and war among one another. All these men look alike. The inhabitants of Quivira are the best of hunters, and they plant maize.”

Juan Jaramillo, who was on the expedition, also gave an account that confirms the description given by Coronado, saying that the only metal found in Quivira consisted of some iron pyrites and a few pieces of copper. As the main objective of the visit was to find gold and silver, the disappointment of the Spaniards can be readily imagined.

The “prunes” mentioned by Coronado were no doubt the wild plums that abound along the streams in central and western Kansas; the “fat,” black and well-watered land answer the description of the soil about the junction of the Smoky Hill and Republican Rivers; and the statement that Quivira was in the 40th degree bears out the belief that the ancient province was somewhere in central or northeastern Kansas, as the northern boundary of the state is the 40th parallel of north latitude. Garcia Lopez de Cárdenas, the expedition historian, bears out the description of the houses given by Coronado, saying: “The houses are round, without a wall, and they have one story like a loft, under the roof, where they sleep and keep their belongings. The roofs are of straw.”

Wichita Grass Hut, 1927, by Edward S. Curtis

From the fact that the people lived in straw houses, or at least in huts with roofs of straw, historian Frederick Hodge identified the inhabitants of Quivira as the Wichita Indians, which tribe, of all the Plains Indians, were accustomed to thatch their huts with straw.

Adolph Bandelier, in his Gilded Man, after a careful analysis of the various accounts of Quivira, sums up the results of his research as follows: “I have shown that Quivira was in central Kansas, in the region of Great Bend and Newton, and a little north of there. It is also clear that the name appertained to a roving Indian tribe rather than a geographical district. Hence, when I say that Coronado’s Quivira was there, the identification is good for the year 1541 and not for a later time. The tribe wandered with the bison, and with the tribe, the name also went hither and thither.”

Suppose Bandelier is correct in his deductions, as he probably is. In that case, the fact that the name wandered with the tribe may account for the various locations of Quivira province, though, as he shows, the Quivira visited by Coronado in 1541 was unquestionably somewhere within the present limits of the State of Kansas. Bandelier also says: “With the return to Mexico of the little army that Coronado commanded, the name of Cibola lost its fascination. But Quivira continued to exercise an unperceived influence on the imagination of men. Notwithstanding, or perhaps because Coronado had told the unadorned truth concerning the situation and conditions of the place, the world presumed that he was mistaken and insisted on continuing the search for it.”

Although many of the Spaniards in Mexico believed that vast wealth was to be found in Quivira, no attempt was made to visit the province for more than half a century after the expedition of Coronado. Then came the expedition of Francisco Leyva de Bonilla in 1595 and Juan de Oñate in 1601, but both were undertaken without adequate preparations and conducted in such a lax and desultory manner that nothing was accomplished.

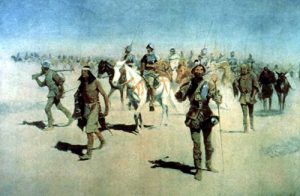

Coronado’s Expedition by Frederic Remington

After the insurrection of 1680 and the reconquest of New Mexico by Diego de Vargas in 1692-94, the name Quivira, as applied to an interior province or the tribe inhabiting it, seems to have been lost. But the recollection of the golden stories was not allowed to perish, and the myth was transferred to some ruins in what is now Socorro County, New Mexico, about 150 miles south of Santa Fe, which ruins became popularly known as “La Gran Quivira.”

To quote again from Bandelier: “The treasure city had lain in ruins since the insurrection of 1680; but its treasures were supposed to be buried in the neighborhood, for it was said there had once been a wealthy mission there, and the priests had buried and hidden the vessels of the church. Thus the Indian kingdom of Quivira of ‘the Turk’ was metamorphosed in the course of two centuries into an opulent Indian mission and its vessels of gold and silver into a church service. But where Quivira should be looked for was forgotten.”

In the late 19th century, efforts were made to ascertain the location of the lost Quivira. The translation of Castaneda’s narrative of the Coronado Expedition by George Winship; the work of the Hemenway archaeological expedition; the investigations and researches of James H. Simpson, Frederick Hodge, and others, who have studied and carefully compared the directions and distances given in the relations concerning the movements of Coronado, all point to the region between the Arkansas and Kansas Rivers as the site of the ancient Indian province.

Jacob V. Brower, an archaeologist of St. Paul, Minnesota, made three trips to Kansas to determine, if possible, the location of the original Quivira. The first of these trips was made in November 1896, the second in March 1897, and the third in March 1898. Brower explored the valleys of the Kansas and Smoky Hill Rivers from the mouth of Mill Creek in Wabaunsee County to Lyon Creek in Dickinson County and the Arkansas River Valley in the vicinity of Great Bend. Through the testimony of stone implements, a method criticized as untrustworthy, he determined the location of six ancient villages. Of these, 11 were in Pottawatomie County, 10 in Wabaunsee, 11 in Riley, 20 in Geary, four in Dickinson, six in McPherson, and one each in Marion, Rice, and Barton Counties. On October 29, 1901, the Quivira Historical Society was organized at Alma, Kansas, the county seat of Wabaunsee County. One of the society’s principal objectives was erecting monuments marking specific historical sites. On August 12, 1902, the first of these monuments was unveiled at Logan Grove, near Junction City. More monuments were also erected in Dickinson, Riley, and Wabaunsee Counties.

~~

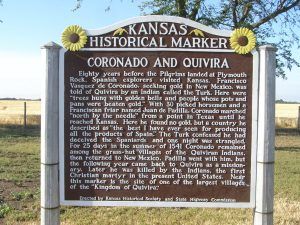

Kansas marker giving a brief history of Coronado’s travels to the area in 1541 located along US Hwy 56 west of Lyons, Kansas.

Today, a historical marker is located on U.S. Highway 56 between Lyons and Chase in Rice County. The marker reads:

“Eighty years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, Spanish explorers visited Kansas. Seeking gold in New Mexico, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado was told of Quivira by an Indian called the Turk. Here were “trees hung with golden bells and people whose pots and pans were beaten gold.” With 30 picked horsemen and a Franciscan friar named Juan de Padilla, Coronado marched “north by the needle” from a point in Texas until he reached Kansas. Here he found no gold but a country he described as “the best I have ever seen for producing all the products of Spain.” The Turk confessed he had deceived the Spaniards and one night was strangled. For 25 days in the summer of 1541, Coronado remained among the grass-hut villages of the Quiviran Indians, then returned to New Mexico. Padilla went with him but came back to Quivira as a missionary the following year. Later he was killed by the Indians, the first Christian martyr in the present United States. Near this marker is the site of one of the largest villages of the “Kingdom of Quivira.”

A museum is also dedicated to the site in Lyons, Kansas. The Coronado-Quivira Museum displays artifacts and information on early inhabitants, Spanish explorers, the Sante Fe Trail, and the coming of homesteaders and permanent settlers. It is located at 105 West Lyon in Lyons, Kansas.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated February 2023.

About the Article: The majority of this historic text was published in Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Volume I; edited by Frank W. Blackmar, A.M. Ph. D.; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912. However, the text that appears on this page is not verbatim, as additions, updates, and editing has occurred.