Bleeding Kansas & the Missouri Border War – Legends of America (original) (raw)

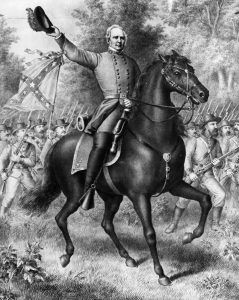

John Brown.

Bleeding Kansas, or the Kansas-Missouri Border War, was a series of violent civil confrontations between the people of Kansas and Missouri that occurred immediately after the signing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. The border war started seven years before the Civil War officially began and continued into the war. The issue was whether or not Kansas would become a Free-State or a pro-slavery state, which resulted in years of electoral fraud, raids, assaults, and retributive murders carried out by pro-slavery “Border Ruffians” in Missouri and anti-slavery “Jayhawkers” and “Redlegs” in Kansas.

Martial Law in Missouri by George Caleb Bingham, 1870.

“Come on, then, gentlemen of the slave states. Since there is no escaping your challenge, we accept it in the name of freedom. We will engage in competition for the virgin soil of Kansas, and God give the victory to the side which is stronger in numbers, as it is in right.

— Senator William Seward, on the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, May 1854

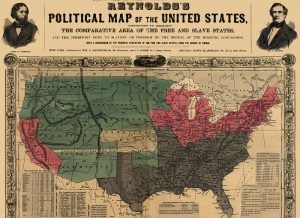

1856 map showing slave states in gray, free states in pink, U.S. territories in green, and Kansas in white.

On May 30, 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was signed, which opened the two territories to white settlement primarily so that a railroad could be built across the vast plains to the Rockies. Though the area was reserved for the Indians, the treaty was disregarded with the coming of the steam engine. Little did those long-ago legislators realize the chain of events they had set in motion that would end in the Civil War and usher in an era of violence that would plague the plains for the rest of the century.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act also repealed the Missouri Compromise and reopened the issue of extending slavery north, allowing the two territories to decide the matter. As a result, settlement of the state was spurred, not so much by westward expansion as by the determination of both pro-slavery and abolitionist factions to achieve a majority population in the territory.

Prologue to the Civil War.

With congressional power in the Southerners’ grip, the federal government placed the volatile issue of slavery into the hands of those settling the new territories. Abolitionists, extreme in New England, were pitted against Southerners, who realized that if Kansas became a Free-State, their strength in Congress would be eroded. This tip in congressional power threatened their political, economic, and cultural existence in the South.

New England abolitionists soon began organizing emigrant aid societies to encourage like-minded citizens to settle in the new territory. One of the men who joined the New England Emigrant Society and settled in Kansas for several years was Horace Tabor, who later moved on to Leadville, Colorado, and became known as the famous “Silver King.”

Pro-slavery interests in and throughout the South took counteraction. Each faction established towns in Lawrence and Topeka by the Free-Staters and Leavenworth and Atchison by the pro-slavery settlers.

On August 1, 1854, 29 northern emigrants, mainly from Massachusetts and Vermont, were the first to arrive in Lawrence, Kansas, named for Amos A. Lawrence, a promoter of the Emigrant Aid Society. A second party of 200 men, women, and children arrived in September. Soon, all the tasks required to organize a new territory for statehood would become secondary to the single issue of slavery.

The First Territorial Capitol at Pawnee, Kansas, was only used for one session before moving to Lecompton, Kansas, when the pro-slavery advocates controlled the state. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

On October 16, 1854, the first anti-slavery newspaper was established to voice the New England Emigrant Society’s sentiments. The newspaper called the Kansas Pioneer further enraged the pro-slavery supporters.

Pro-slavery Missourians flooded the state to vote at the first election in November 1854, where armed pro-slavery advocates intimidated voters and stuffed ballot boxes. Andrew H. Reeder was elected as the first territorial governor of Kansas.

Another election was held in March 1855 for the first territorial legislature. With the pro-slavery advocates winning again, the members ousted all Free-State members, secured Governor Andrew Reeder’s removal, adopted pro-slavery statutes, and began to hold their sessions at Lecompton, Kansas, about twelve miles from Lawrence. Severe penalties were leveled against anyone who spoke or wrote against slaveholding, and those who assisted fugitives could be put to death or sentenced to ten years of hard labor.

In July 1855, Kansas’s first territorial capital was completed of native stone at the now-extinct town of Pawnee on the Fort Riley reservation. However, its use was short-lived due to its distance from Missouri and the pro-slavery faction controlling the Kansas legislature.

John Brown, 1850s.

Though the pro-slavery tickets had won the earlier elections in 1854 and 1855, free-soilers did not accept the results, and a rival government was set up at Topeka in October 1855. Southern sympathizers – not only from Missouri but from as far away as Alabama – began to form paramilitary bands to destroy the abolitionist power in Kansas.

On October 7, 1855, John Brown arrived in Osawatomie, Kansas, to join his five sons engaged in the fight for the Free State cause. At first, Brown was reluctant to join his sons because he was 55. But a letter from his son, John Jr., requesting arms changed his mind. Packing a wagon, he headed west, gathering weapons along the way and declaring, “I’m going to Kansas to make it a Free State.”

On December 1, 1855, a small army of Missourians, acting under the command of “Sheriff” Jones, laid siege to Lawrence in the opening stages of what would later become known as “The Wakarusa War.” The intervention of the new governor, Wilson Shannon, kept the pro-slavery men from attacking Lawrence.

But, later, when a young man, who had come to the aid of the Free-Staters, rode off to his home about six miles west of Lawrence, he was met by a group of pro-slavery men from Lecompton.

Though the man never drew his weapon, he was shot in cold blood by the pro-slavery faction. His body was returned to Lawrence, where the entire citizenry followed it to its burial in the presence of his young wife and children in Pioneer Cemetery. More than any other, this event hardened the Free-Staters to realize that they had come not simply for an election to determine whether Kansas would be a free or slave state but to fight a war over the issue.

“They may kill me, but they cannot kill the principles I fight for. If they take Lawrence, they must do it over my dead body.”

— G.W. Bell, Douglas County Clerk

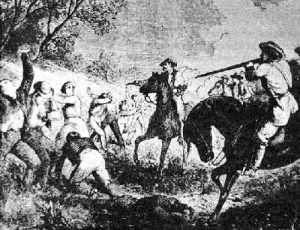

Anti-slavery Jayhawkers clashed with Bushwhackers from neighboring Missouri. The two sides were provoked into bitter and often bloody struggles in Kansas Territory to sway the popular decision in their favor.

Missouri Border Ruffians.

Both sides were abetted by desperadoes and opportunists, where people were tarred, feathered, kidnapped, and killed. Confrontation and deadly skirmishes over the issue of slavery would continue in the Kansas Territory for the next five years in an era to be forever known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

The word Jayhawker came from a mythical bird that cannot be caught. At first, the term was applied to both the pro-slavery and abolitionist rebel bands. But, before long, it stuck to the anti-slavery side only. Those who favored the Confederacy soon earned the name of Bushwhackers because they primarily lived in the “bush,” or country, and their legs “whacked” the bushes as they rode. Both sides eventually included semi-legitimate soldiers, even grudgingly acknowledged by the Union and Confederate forces. However, other members of these two groups were bandits with a quasi-military excuse for ambush, robbery, murder, arson, and plunder.

In 1856, the pro-slavery territorial capital was “officially” moved to Lecompton, Kansas. In April of that year, a three-man congressional investigating committee arrived in Lecompton to investigate the Kansas troubles. The majority committee report found the elections fraudulent and said the Free-State government represented the majority’s will. However, the federal government refused to follow its recommendations and continued to recognize the pro-slavery legislature as the legitimate government of Kansas.

On May 21, 1856, a motley group of more than 500 armed pro-slavery enthusiasts raided Lawrence, the abolitionist movement’s stronghold. They burned the Free-State Hotel (now the Eldridge Hotel), smashed the presses of two Lawrence newspapers, ransacked homes and stores, and killed one man.

Senator Charles Sumner Attacked.

Not only was violence erupting in Kansas but also in Congress itself. On May 22, 1856, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner was beaten unconscious by Preston Brooks, a congressman from South Carolina. Just three days previously, Sumner had made a fiery speech called “The Crime Against Kansas,” in which he accused pro-slavery senators, particularly Stephen Douglas of Illinois and Andrew Butler of South Carolina, of cavorting with “the harlot, Slavery.” Preston Brooks, the nephew of Andrew Butler, believing that Sumner had insulted his uncle, walked into Sumner’s chambers, where he slammed a metal-topped cane onto his head time and time again. His injuries stopped Sumner from attending the Senate for the next three years.

The caning of Sumner became a symbol in the North of Southern brutality. Meanwhile, while Brooks was initially censured for his actions, he became a hero in the South for defending the Southern honor and was subsequently reelected by his constituency.

On May 24, 1856, John Brown, self-appointed avenger, four of his sons, and two other followers raided a settlement on the Pottawatomie Creek in Franklin County, Kansas, dragging five innocent pro-slavery men from their homes. They hacked them to death with artillery swords. After Osawatomie, John Brown earned the nickname “Osawatomie Brown” as he led anti-slavery guerrillas in the fight for a free Kansas for the rest of the year.

In retaliation, the town of Osawatomie was attacked by 400 pro-slavery Missourians in August 1856. Along with 40 other men, John Brown defended the town, but in the end, the invaders burned all but four homes at the settlement, and John Brown’s son Frederick was killed. When the invading army returned, four wagonloads of dead and wounded were brought into Boonville, Missouri.

In September 1856, a new territorial governor, John W. Geary, arrived in Kansas and restored order. However, his tenure was short as, in 1857, the Lecompton legislature met. It became clear that free elections would not be held to approve a new constitution, and Geary resigned. Robert J. Walker was then appointed governor, and a convention was held at Lecompton, where a constitution was drafted. Only that part of the resulting pro-slavery constitution dealing with slavery was submitted to the electorate, and the question was drafted to favor the pro-slavery group. Free-State men refused to participate in the election because the constitution was overwhelmingly approved.

William Quantrill.

1857 was also the year that William Clarke Quantrill arrived on the scene. The former Ohio schoolteacher moved to Kansas and took up farming. However, he quickly honed his violent nature by living with thieves and murderers, committing several brutal murders during this time. The following year, he rode West with a wagon train, supporting himself through gambling. Later, he returned and actively participated in the bloody battle between Kansas and Missouri.

Despite the dubious validity of the Lecompton Constitution, President James Buchanan recommended, in 1858, that Congress accept it and approve statehood for the territory. Instead, Congress returned it for another territorial vote, moving the nation closer to war.

Marais des Cygnes Massacre, Kansas.

On May 19, 1858, an armed action would shock the nation and become known as the Marais des Cygne Massacre. After a raid through Kansas, where several unarmed Free Staters were killed, Georgia native Charles Hamelton and about 30 followers returned to Missouri when they captured eleven Free State men near the Marais des Cygnes River on the Kansas-Missouri border. Many of these captives, some former neighbors of Hamelton’s, expected no harm from him. However, the Bushwhackers herded the captives into a ravine, shot them, left them for dead, and returned to Missouri.

Of the eleven Free Staters, five men died, five were wounded, and one, who had faked death to escape injury, crawled from the ravine to tell his tale to the nation. Baptist minister Reverend Benjamin L. Read immediately began to spread the word of the massacre, which abolitionist writer John Greenleaf Whittier soon chronicled in a poem that appeared in the September 1858 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. As Whittier had intended, the story further inflamed abolitionist sentiment. The last verse of the poem reads:

On the lintels of Kansas

that blood shall not dry;

Henceforth the Bad Angel

Shall harmless go by;

Henceforth to the sunset

Unchecked on her way,

Shall Liberty follow

The march of the day.

Constitutional Convention, Topeka, Kansas, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1855.

Finally, in July 1859, a Free-State constitution was adopted after several attempts to draft one that Kansas could use to apply for statehood. The constitution, which forbade slavery, was accepted by Congress; however, the pro-slavery forces in the Senate strongly opposed Kansas’ Free-State status and stalled its admission. The Kansas conflict and statehood question became a national issue and figured into the 1860 Republican party platform.

After bloody encounters like Pottawatomie Creek, John Brown returned east and began to amass arms, making battle plans in earnest for a full-fledged invasion of the South. This plan culminated in the raid on Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. However, they were trapped once John Brown and his followers had captured the arsenal. They were then captured and turned over to state authorities.

John Brown was found guilty, sentenced to death, and hanged in Charles Town, West Virginia, on December 2, 1859

In 1860, Charles R. “Doc” Jennison, leader of a Jayhawker band, headed a posse that hanged two Missourians caught trying to return fugitive slaves to their masters.

“God sees it; I have only a short time to live–only one death to die, and I will die fighting for this cause; there will be no more peace in this land until slavery is done for.

– John Brown to his son, as they watched Osawatomie burn on August 30, 1856

On January 29, 1861, Kansas was finally admitted to the Union as a Free State. Her struggle over the still unsettled slavery issue came at a terrible cost, providing a last ominous warning of the peril awaiting the nation. Topeka became the state capital, with Charles Robinson as the first governor and James H. Lane, an active free stater and U.S. Senator.

John Brown 1859.

The toll was only a foretaste of the suffering of Kansas and Missouri during the Civil War. In these two states, the war was fought with the particular ferocity that comes when relatives and close neighbors fall out. The five-year border conflict had brought the nation, month by month, inevitably to the brink of Civil War. This brutal and bloody struggle between Free-State and pro-slavery factions in Kansas Territory was a warning and a chilling prelude for the controversy that would soon engulf the entire country. Before long, the entire nation would know its dreadful fate when, in April 1861, the Civil War began.

Though Kansas had suffered terribly in the years preceding the Civil War and would continue to be a battleground for partisan bands on both sides, the war would extol an appalling price for Missouri. While Missouri was officially a Union state, never declaring to join the Confederacy, most of its population was pro-slavery. This resulted in a war between the U.S. Army and Missouri citizens within its borders. Because of this, the State of Missouri never officially joined the Civil War due to its internal struggles.

While the various political arguments that led to the war developed, the Missouri people tried to maintain neutrality. As the southern states seceded, Missouri and Arkansas held to the Union one by one. Finally, their position became impossible when President Lincoln ordered Missouri and Arkansas to raise a quota of men to help force the rebel states back in line. Unwilling to fight old friends, neighbors, and families, both states refused, with Arkansas seceding on May 6, 1861. Missouri was now faced with a difficult choice. Hamilton R. Gamble, future provisional Governor, had to say of the situation, “Our sympathies are with the South, but our best interests are with the North.”

Confederate Flag.

Six days after the President’s call for troops, Confederate sympathizers seized the federal arsenal at Liberty, Missouri, on April 20, 1861.

With the official declaration of the Civil War, anti-Union Missourians, who had formerly been content to terrorize abolitionists in Kansas, extended their operations into their native state, raiding pro-Union towns, ambushing Army columns, and generally scouring the countryside, looting, and killing. Meanwhile, the Jayhawkers increased their presence in Missouri, and their crimes became more ruthless.

Missourians’ attempts to get the government to control the destruction went unheeded, and many Missourians joined Partisan Groups, secretly pledging their loyalty to the Confederacy but retaining their civilian status. They aided the Confederacy by supplying them with food, shelter, and clothing and revealing troop movements. The joining of the Partisan group was not always intended to support the Southern cause but, instead, in retaliation against the crimes committed against them by the Federals. The Missouri Partisan Rangers formed their own army to fight the Union troops, supporting the Confederacy because they shared the same enemy but not necessarily the same cause.

The next internal battle in Missouri occurred on May 10, 1861, in St. Louis, which became known as the “Camp Jackson Massacre.” Missouri’s pro-southern governor, Claiborne Fox Jackson, attempted to force secession with a secret plan to obtain control of the guns and ammunition stored at the U.S. Arsenal in St. Louis. He ordered the State Guard to meet at Camp Jackson, planning to march on the arsenal. However, the “Home Guard” of German troops led by Captain Nathaniel Lyon descended upon Camp Jackson from several directions.

Camp Jackson Massacre.

Lyon demanded unconditional surrender, which he received. His force, numbering 7,000 men, marched its prisoners through the city while hostile crowds shouted insults and threw rocks. The troops fired several volleys into the crowd, whose members then drew their weapons and returned the fire.

When it was said and done, twenty-eight lay dead or wounded in the streets. A baby, two innocent men, and many other innocent bystanders were wounded in the melee. St. Louis continued to be subject to chaos and sporadic violent outbreaks for the next month.

Yet another skirmish between Missouri State and Federal forces occurred at the Battle of Boonville on June 17, 1861, when Captain Lyon intended to put down Jackson’s State Guard. As the guard retreated towards Boonville, Lyon embarked on steamboats, transported his men below Boonville, marched to the town, and engaged the enemy. In a short fight, Lyon dispersed the Confederates and occupied Boonville. This early victory established Union control of the Missouri River and helped douse attempts to place Missouri in the Confederacy.

In the summer of 1861, Kansas Senator James H. Lane returned to his home state to command “Lane’s Brigade.” Supposedly composed of Kansas infantry and cavalry, the force was more akin to a ruthless band of Jayhawkers wearing United States uniforms. As he rampaged through Missouri, his antics earned him the nickname of the “Grim Chieftain” for the death and destruction he brought to the people of Missouri.

General James H. Lane.

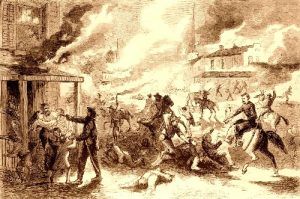

In September of 1861, Lane’s Brigade descended on Osceola, Missouri. When Lane’s troops found a cache of Confederate military supplies in the town, Lane decided to wipe Osceola from the map.

First, Osceola was stripped of its valuable goods and loaded into wagons taken from the townspeople. Then, nine citizens were given a farcical trial and shot. Finally, Lane’s men brought their frenzy of pillaging and murder to a close by, burning the entire town. The settlement suffered more than $1,000,000 worth of damage, including that belonging to pro-Union citizens.

In 1862, Quantrill began his infamous raiding career in western Missouri and crossed the border into Kansas by plundering Olathe, Spring Hill, and Shawnee. His raids gained the attention of other desperados. By 1863, Quantrill recruited others who joined his company, including “Bloody” Bill Anderson, Frank, and Jesse James.

William Clarke Quantrill was the most infamous of the leaders of the Missouri partisan units. A daring and ruthless man, Quantrill directed his men in raids along the Kansas–Missouri border. Many military men on both sides condemned his brutal tactics, and one Confederate general even threatened to arrest him and all of his men.

William Clarke Quantrill, an Ohio native, had joined the Confederate forces several years prior but was unhappy with their reluctance to prosecute Union troops aggressively. Therefore, the young man took it upon himself to take a more forceful course with his own guerrilla warfare.

Independence, Missouri.

On August 11, 1862, Colonel J.T. Hughes’s Confederate forces, including William Quantrill, attacked Independence, Missouri, at dawn. They drove through the town to the Union Army camp, capturing, killing, and scattering the Yankees.

During the melee, Colonel Hughes was killed, but the Confederates took Independence, which led to Confederate dominance in the Kansas City area for a short time. Quantrill’s role in the capture of Independence led to his being commissioned as a captain in the Confederate Army.

On August 15, 1862, Union Major Emory S. Foster led an 800-man combined force from Lexington to Lone Jack. Upon reaching the Lone Jack area, he discovered 1,600 Rebels under Colonel J.T. Coffee and attacked them at about 9:00 pm, dispersing the Confederate forces.

Early the following day, the rebels counter-attacked with a 3,000-man force. After a five-hour battle, Foster and Coffee died, and the Union forces retreated. Though resulting in a Confederate victory, the Lone Jack Battle was one of the bloodiest fought on Missouri soil, leaving 200 men dead, dying, or wounded and multiple homes and businesses in ashes.

Quantrill’s Raiders sacking a town.

On October 17, 1862, Quantrill and his band moved to attack Shawnee, Kansas. As they neared their destination, they came upon a Federal supply train, where they captured twelve unarmed men. Later, these 12 drivers and Union escorts would be found dead, all but one shot in the head. Quantrill and his men attacked the town, killing several men and burning the settlement.

In May 1863, Quantrill and his band moved to the Osage River banks on the Missouri-Kansas border. Brigadier General Thomas Ewing, Jr. from Kansas, who commanded the district border, was unhappy with Quantrill’s presence.

To destroy the guerrillas’ support base, Union troops began to arrest Kansas City area women in July 1863 who were supporting the Bushwhackers or suspected of gathering information on the partisans’ behalf. The Border Ruffians’ known relatives, including “Bloody Bill” Anderson and the Younger Brothers family members, were particularly interesting to the Federal Troops. Detaining them in several buildings throughout the Kansas City area, women and children were detained until they could be transported out of the area and tried. Overcrowded and infested with rats and vermin, the women and children in these buildings suffered inexplicably.

One such dilapidated three-story building in downtown Kansas City was deplorable, with a weak foundation and plaster constantly falling from the walls and ceilings. Though signs that it was unstable were noted, such as large cracks in the walls and ceilings and large amounts of mortar dust on the floor, the signs were ignored. The building collapsed on August 13, 1863, killing five women and injuring dozens of others.

Women who were close relatives of prominent Confederate guerrillas were killed and injured in the collapse. Those killed in the collapse included Josephine Anderson, sister of “Bloody Bill” Anderson, Susan Crawford Vandever and Armenia Crawford Selvey, Cole Younger’s cousins, Charity McCorkle Kerr, wife to Quantrillian member Nathan Kerr, and a woman named Mrs. Wilson. Many others were injured and scarred. Caroline Younger, sister to Cole and James Younger, would die two years later due to her injuries. Another Anderson sister was crippled for life when both of her legs were broken in the incident.

When news of the collapse reached the families of the dead and injured, they went wild. Soon, crowds gathered around the ruins as the dead and wounded were carried off, shouting “Murder!” at the Union forces. Just four days later, on August 18, 1863, General Ewing issued General Order Number 10, which “officially” stated that any person – man, woman, or child – who was directly involved with aiding a band of guerrillas would be jailed.

Later, Quantrill and his men would claim that the building was deliberately weakened, giving them ammunition for the infamous attack on Lawrence that was about to come.

Lawrence was a town long hated by Quantrill and his men. Home of the demagogic anti-slavery Senator, Jim Lane, was also a stronghold of the Red Legs, Union guerrillas who had sacked much of western Missouri. An attack on this citadel of abolition would bring revenge for any wrongs that the Southerners had suffered, real or imagined.

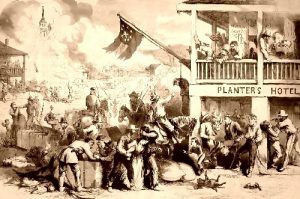

The Lawrence, Kansas Raid, illustrated in Harper’s Weekly, September 1863.

Early on August 21, 1863, Quantrill, along with his murderous force of about 400, descended on the still-sleeping town of Lawrence. Incensed by the Free-State headquarters town, Quantrill set out to take revenge against the Jayhawker community. In this carefully orchestrated early morning raid, in four terrible hours, he and his band turned the town into a bloody and blazing inferno unparalleled in its brutality.

Quantrill and his bushwhacker mob of raiders began their reign of terror at 5:00 am, looting and burning as they went, bent on the town’s destruction, then less than 3,000 residents. By the time it was over, they had killed approximately 180 men and boys and left Lawrence nothing but smoldering ruins.

In response to the Lawrence Massacre, Union Brigadier General Thomas Ewing signed General Order No. 11 on August 25, 1863, which required all persons living more than one mile from Independence, Hickman’s Mill, Pleasant Hill, and Kansas City to leave their farms unless they took an oath of loyalty to the Union. The cities that were excluded were already under Union control. This order included Cass, Jackson, Bates, and portions of Vernon Counties. Some did take the oath, but others fled to other areas, never returning. The Union Army burned the remaining homes, buildings, and crops, and the entire area became known as “No Mans Land.”

Evacuation of Missouri Counties under General Order No. 11, painting by George Caleb Bingham, 1870.

By denying Quantrill and his guerillas the populace’s support, the Union hoped to force them out in the open, where they could be destroyed. The enforcement of Order No. 11 resulted in terrible hardships for the people of Jackson County. Many Union and Southern families alike were killed in the ensuing melee.

By October, Quantrill and his men rode south toward Texas to spend the winter. His men attacked a column of Union cavalry and wagons near Baxter Springs, Kansas. Then they captured Fort Blair, commanded by Union Major General James Blunt. Blunt escaped to nearby Fort Scott, but more than 80 of his soldiers (60 were black) were captured and massacred. Blunt was relieved of command as a result. Later, a drunken Quantrill boasted that he had accomplished in one day what Confederate Colonel Jo Shelby and Major General John Marmaduke had failed for years to do — beat Blunt.

Upon his arrival in Texas, Quantrill reported at Bonham on October 26, 1863, to General Henry E. McCulloch. Quantrill and his men were ordered to help round up the increasing number of deserters and conscription dodgers in North Texas. The band captured a few but killed even more, after which McCulloch pulled them off this duty. The General then sent them to track down retreating Comanche from a recent raid on the northwest frontier, which they did without success.

During this time, Quantrill’s behavior had become too bizarre for many of his men, and he was beginning to lose control over them. Some wanted to join the regular Confederate army. Anderson’s quarrels with Quantrill led him to form a fierce band, including Frank James and his 16-year-old brother, Jesse James. During their winter in Texas, “Bloody Bill” Anderson took his group and began to terrorize the area. Texas residents became targets for so many raids and acts of violence, with two such groups in the neighborhood. Regular Confederate forces had to be assigned to protect residents from the irregular Confederate forces’ activities.

Finally, General McCulloch determined to rid North Texas of Quantrill’s influence, and on March 28, 1864, Quantrill was arrested on the charge of ordering the murder of a Confederate Major. However, Quantrill escaped, returning to his camp near Sherman, Texas, pursued by over 300 state and Confederate troops. His band then crossed the Red River into Indian Territory, where they re-supplied from Confederate stores and started the journey back to Missouri.

Soon, his guerrilla band began to break up into several smaller units. His vicious lieutenant, “Bloody Bill” Anderson, known for wearing a necklace of Yankee scalps into battle, would continue with his band to terrorize the state of Missouri. As Quantrill’s authority over his followers disintegrated, they elected George Todd, a former lieutenant to Quantrill, to lead them.

“Bloody Bill” Anderson.

Anderson’s greatest fame came from a massacre and battle with Union soldiers at Centralia, Missouri, when on September 27, 1864, he led a band of about seventy men into the town. Wearing Confederate uniforms, the ruffians showed no mercy to the Centralia residents as they systematically raided homes and stores, raped and murdered. The entire town was reduced to a burning ruin in their final act of wanton destruction.

After the Centralia Massacre, a Union detachment chased the fleeing guerrillas, who turned on them, killing 114 of their pursuers. On October 11, Anderson’s Bushwhackers sacked Boonville while their leader joined Quantrill to capture Glasgow. Riding with Jo Shelby’s cavalry division, Todd was killed in battle near Independence on October 21, 1864, and Anderson fell five days later in a skirmish near Orrick.

In mid-September 1864, Confederate General Sterling Price made a last-gasp raid across the state, hoping to capture Missouri for the South. The Civil War had raged for nearly 3 1/2 years, and Price, a former Missouri governor, had been actively engaged throughout. Leading pro-Confederate Missouri State Guard troops at the Battles of Lexington, Wilson’s Creek, and Pea Ridge, Price was a favorite of his troops and was affectionately known as “Old Pap.”

Forced to bypass St. Louis because of its overwhelming Federal strength, Price’s troops struggled past Hermann, Boonville, Glasgow, Lexington, and Independence, filling his ranks along the way with fresh volunteers in preparation for an invasion of Westport (now part of Kansas City.) On October 23, 1864, his troops suffered the worst Confederate defeat in Missouri at Westport, finally allowing the Union to regain state control. Westport was the last major Civil War battle west of the Mississippi River.

Exhausted, the fleeing wagon train retired south down the state line. However, Union General Samuel R. Curtis was hot on the Price trail.

After crossing into Kansas, Price and his weary troops camped near a trading post on the night of October 24. The next day, the Rebels, stalled by their wagons crossing the ford, had formed a line on the north side of Mine Creek. The Federals, although outnumbered, commenced the attack as additional troops arrived during the fight.

Colonel Sterling Price

They soon surrounded the Confederates, capturing about 600 men and two generals – Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke and General William L. Cabell. Having lost these many men, Price’s army was doomed. Retreat to friendly territory was the only recourse.

Meanwhile, Quantrill concocted a plan to lead a company of men to Washington and assassinate President Abraham Lincoln to regain prestige. He assembled a group of raiders in Lafayette County, Missouri, in November and December 1864 to complete this task. However, the strength of Union troops east of the Mississippi River convinced him that his plan could not succeed. Quantrill turned back and resumed his typical pattern of raiding.

On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee formally surrendered at Appomattox, effectively ending the Civil War. However, while peace was brought to the rest of the land, the violence in these two states would continue for years.

Fearing capture and execution, Quantrill and his men headed east. In May 1865, an irregular Unionist force surprised his group near Taylorsville, Kentucky, and in the ensuing battle, Quantrill was shot through the spine. He died at the military prison in Louisville, Kentucky, on June 6, 1865.

Conquered Banner of the Confederacy.

The divided state of Missouri suffered the third-largest number of engagements during the war at 1,162. Only Virginia and Tennessee had more. 40,000 Missourians joined the Confederate ranks, while nearly three times that number joined the Union Army. When it was over, Missouri lost 27,000 of its brave sons.

Kansas contributed 20,097 men to the Union Army, a remarkable record since the population included less than 30,000 men of military age. Furthermore, Kansas suffered the highest mortality rate of any Union state. Of the black troops in the Union army, 2,080 were credited to Kansas, though the 1860 census listed fewer than 300 blacks of military age in the state; most came from Arkansas and Missouri.

Having tasted the excitement of gunplay, members of the guerrilla bands were in no mood to lay down their arms meekly and become model citizens. Their resolve to continue their outlaw ways was strengthened by knowing that surrender meant the hangman’s noose. Men like Jesse, Frank James, and the Younger Brothers merely shifted their field of endeavor from the political to the financial. Continuing to apply their hit-and-run tactics, bank robberies and train holdups now became endemic, effectively beginning the advent of the Wild Wild West and its many outlaws.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

Author’s Notes:

Glorious Banner.

What an exciting piece of history to explore! Did you know that most historians believe the Civil War began due to what has become known as “Bleeding Kansas?” When the Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed the Kansas Territory to be settled and eventually become a state, many people fervently believed that by becoming a “Free-State,” the tides could be turned into the ongoing issue between pro-slavery advocates and abolitionists.

Another interesting point was that we received varying stories when visiting Kansas and Missouri sites while researching this article. When we visited the Mine Creek Civil War Battlefield in Kansas, we were told that the hostilities between Missouri and Kansas still exist today, albeit to a much lesser degree. Though Legends of America is based in Missouri, we are not native to the area and were surprised to hear this. However, we found evident disparities when we began researching this fascinating story. The sentiments of the Civil War generation have been passed down for well over a century.

For instance, when doing an internet search, you will get a very different story when searching for “Bleeding Kansas” than when searching for “Missouri Civil War .” Many of the available books are no different. Though most lean toward the Kansas side of the conflict due to its anti-slavery sentiment, Missouri cannot be ignored in its contribution to history and its heavy losses during the Civil War. Officially, a Union State, Missouri, was internally divided between its pro-slavery sentiments and its obligation as a Union State. Never officially entering the Civil War, Missouri fought internal battles between the Federal Officers and its State Forces.

Jayhawkers and Bushwackers fight it out over Kansas becoming a Free-State or a pro-slavery state.

Even when we visited Kansas and Missouri’s historical sites, we got a different impression of the “telling.” Kansas sites will focus on the great battle of Mine Creek, where the Union Forces won the skirmish against the Confederates at immense odds; the Lawrence Massacre by Quantrill’s Raiders, or, upon John Brown, the fanatic abolitionist, and his actions to defeat the Missouri Bushwhackers.

In Missouri, we heard the stories of the burning of Osceola by Lane’s Kansas Brigade, the attack upon the Missouri building that killed many innocent women and children, and the forcible evacuation of Kansas City area counties that displaced many Missourians and turned the area into a desolate “No Mans Land.”

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated October 2024.

Also See:

Lawrence, Kansas – From Ashes to Immortality

Osceola, Missouri – Surviving All Odds

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William; History of the State of Kansas, A.T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

The Kansas Collection

Kansas Memory

Kansas State Historical Society

National Park Service

Territorial Kansas

Wikipedia

More Kansas Resources