Populating Boot Hill in Dodge City, Kansas – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By Robert M. Wright in 1913

Dodge City Boot Hill Cemetery, courtesy Boot Hill Museum

The first man killed in Dodge City was a big, tall, black negro by the name of Tex, and who, though a little fresh, was inoffensive. He was killed by a gambler named Denver. Mr. Kelly had a raised platform in front of his house, and the darky was standing in front and below, in the street, during some excitement. There was a crowd gathered, and some shots were fired over the heads of the crowds when this gambler fired at Texas, and he fell dead. No one knew who fired the shot and they all thought it was an accident, but years afterward the gambler bragged about it. Some say it was one of the most unprovoked murders ever committed, and that Denver had not the slightest cause to kill, but did it out of pure cussedness when no one was looking. Others say the men had an altercation of some kind, and Denver shot him for fear Tex would get the drop on him. Anyhow, no one knew who killed him, until Denver bragged about it, a long time afterward, and a long way from Dodge City, and said he shot him in the top of the head to see him kick.

The first big killing was down in Tom Sherman’s dance hall, some time afterward, between gamblers and soldiers from the fort, in which row, I think, three or four were killed and several wounded. One of the wounded crawled off into the weeds where he was found next day, and, strange to say, he got well, although he was shot all to pieces. There was not much said about this fight, I think because a soldier named Hennessey was killed. He was a bad man and the bully of the company, and I expect they thought he was a good riddance.

Before this fight, there was “a man for breakfast,” to use a common expression, every once in a while, and this was kept up all through the winter of 1872. It was a common occurrence; in fact, so numerous were the killings that it is impossible to remember them all, and I shall only note some of them.

A man by the name of [William “Billy”] Brooks, acting assistant-marshal, shot Browney, the yard-master, through the head-over a girl, of course, by the name of Captain Drew. Browney was removed to an old deserted room at the Dodge House, and his girl, Captain Drew, waited on him, and indeed she was a faithful nurse. The ball entered the back of his head, and one could see the brains and bloody matter oozing out of the wound until it mattered over. One of the finest surgeons in the United States army attended him. About the second day after the shooting, I went with this surgeon to see him.

He and his girl were both crying; he was crying for something to eat; she was crying because she could not give it to him. She said: “Doctor, he wants fat bacon and cabbage and potatoes and fat greasy beef and says he’s starving.” The doctor said to her: “Oh, well, let him have whatever he wants. It is only a question of time, and short time, for him on earth, but it is astonishing how strong he keeps. You see, the ball is in his head, and if I probe for it, it will kill him instantly.”

Now there was no ball in his head. The ball entered one side of his head and came out the other, just breaking one of the brain or cell pans at the back of his head, and this only was broken. The third day and the fourth day he was alive, and the fifth day they took him east to a hospital. As soon as the old blood and matter were washed off, they saw what was the matter, and he soon got well and was back at his old job in a few months.

A hunter by the name of Kirk Jordan and Brooks had a shooting scrape on the street. Kirk Jordan had his big buffalo gun and would have killed Brooks, but the latter jumped behind a barrel of water. The ball, they say, went through the barrel, water and all, and came out on the other side, but it had lost its force. We hid Brooks under a bed, in a livery stable, until night, when I took him to the fort, and he made the fort siding next day and took the train for the East. I think these lessons were enough for him, as he never came back. Good riddance for everybody.

Soiled Dove or Prostitute

These water barrels were placed along the principal streets for protection from fire, but they were excellent protection in several shooting scrapes. These shooting scrapes, the first year, ended in the death of twenty-five, and perhaps more than double that number wounded. All those killed died with their boots on and were buried on Boot Hill, but few of the number in coffins because of the high price of lumber caused by the high freight rates. Boot Hill is the highest and about the most prominent hill in Dodge City and is near the center of the town. It derived its name from the fact that it was the burying ground, in the early days, of those who died with their boots on. There were about thirty persons buried there, all with their boots on and without coffins. Now, to protect ourselves and property, we were compelled to organize a Vigilance Committee. Our very best citizens promptly enrolled themselves, and, for a while, it fulfilled its mission to the letter and acted like a charm, and we were congratulating ourselves on our success. The committee only had to resort to extreme measures a few times and gave the hard characters warning to leave town, which they promptly did. But what I was afraid would happen did happen. I had pleaded and argued against the organization for this reason, namely: hard, bad men kept creeping in and joining until they outnumbered the men who had joined it for the public good — until they greatly outnumbered the good members, and when they felt themselves in power, they proceeded to use that power to avenge their grievances and for their own selfish purposes, until it was a farce as well as an outrage on common decency. They got so notoriously bad and committed so many crimes that the good members deserted them, and the people arose in their might and put a stop to their doings. They had gone too far and saw their mistake after it was too late.

The last straw was the cold-blooded, brutal murder of a polite, inoffensive, industrious negro named Taylor, who drove a hack between the fort and Dodge City. While Taylor was in a store, making purchases, many drunken fellows got into his wagon and drove it off. When Taylor ran out and tried to stop them, they say a man, by the name of Scotty, shot him, and, after Taylor fell, several of them kept pumping lead into him. This created a big row, as the negro had been a servant for Colonel Richard I. Dodge, commander of the fort, who took up his cause and sent some of them to the penitentiary.

Scotty got away and was never heard of afterward.

When railroads and other companies wanted fighting men (or gunmen, as they are now called), to protect their interests, they came to Dodge City after them, and they could sure be found. Large sums of money were paid out to them, and here they came back to spend it.

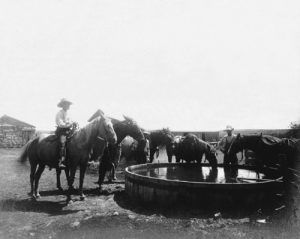

Cowboys at the water tank in Dodge City, Kansas.

This all added to Dodge’s notoriety, and many a bunch of gunmen went from Dodge City. Besides these men being good shots, they did not know what fear was — they had been too well trained by experience and hardships. The buffalo hunters lived on the prairie or out in the open, enduring all kinds of weather, and living on wild game, often without bread, and scarcely ever did they have vegetables of any description. Strong, black coffee was their drink, as water was scarce and hardly ever pure, and they were often out for six months without seeing inside a house. The cowboys were about as hardy and wild as they, too, were in the open for months without coming in contact with civilization, and when they reached Dodge City, they made Rome howl. The freighters were about the same kind of animals, perfectly fearless. Most of these men were naturally brave, and their manner of living made them more so. Indeed, they did not know fear or any such thing as sickness-poorly fed and poorer clad. Still, they enjoyed good pay for the privations they endured, and when these three elements got together, with a few drinks of red liquor under their belts, you could reckon there was something doing. They feared neither God, man, nor the devil, and so reckless they would pit themselves, like Ajax, against lightning if they ran into it.

It had always been the cowboys’ boast as well as a delight to intimidate the officers of every town on the trail, run the officers out of town, and run the town themselves, shooting up buildings, through doors and windows, and even at innocent persons on the street, just for amusement, but not so in Dodge. They only tried it a few times, and they got such a dose, they never attempted it again. You see, here the cowboys were up against a tougher crowd than themselves and equally as brave and reckless, and they were the hunters and freighters — “bull-whackers” and “mule-skinners,” they were called. The good citizens of Dodge were wise enough to choose officers who were equal to the emergency. The high officials of the Santa Fe Railroad wrote me several times not to choose such rough officers — to get nice, gentlemanly, young fellows to look after the welfare of Dodge and enforce its laws.

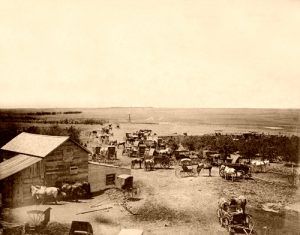

Dodge City Gathering

I promptly answered them that you must fight the devil with fire, and if we put in a tenderfoot for marshal, they would run him out of town. We had to put in men who were good shots and would surely go to the front when they were called on, and these desperadoes knew it. The last time the cowboys attempted to run the town, they had chosen their time well. Late in the afternoon was the quiet time in Dodge; the marshal took his rest then, for this reason. So the cowboys tanked up pretty well, jumped their horses, and rode recklessly up and down Front Street shooting their guns and firing through doors and windows and then making a dash for camp. But before they got to the bridge, Jack Bridges, our marshal, was out with a big buffalo gun, and he dropped one of them, his horse went on, and so did the others. It was a long shot and probably a chance one, as Jack was several hundred yards distant.

There was big excitement over this. I said: “Put me on the jury, and I will be elected foreman and settle this question forever.” I said to the jury: “We must bring in a verdict of justifiable homicide. We are bound to do this to protect our officers and save further killings. It is the best thing we can do for both sides.” Some argued that these men had stopped their lawlessness, were trying to get back to camp, were nearly out of the town limits, and the officer ought to have let them go. If we returned such a verdict, the stockmen would boycott me, and, instead of my store being headquarters for the stockmen and selling them more than twice the amount of goods that all the other stores sold together, they would quit me entirely, and I would sell them nothing.

I said: “I will risk all that. They may be angry at first, but when they reflect that if we had condemned the officer for shooting the cowboy, it would encourage them, and they would come over and shoot up the town, regardless of consequences, and in the end, there would be a dozen killed.” I was satisfied the part we took would stop it forever, and so it did. As soon as the stockmen got over their anger, they came to me and congratulated me on the stand I took and said they could see it now in the light I presented it. There was no more shooting up the town. Strict orders were given by the marshal, when cowboys rode in, to take their guns out of the holsters, and bring them across to Wright & Beverley’s store, where a receipt was given for them. And, my! what piles there were of them. At times they were piled up by the hundred. This order was strictly obeyed and proved to be a grand success because many cowboys would proceed at once to tank up. Many would have been the killings if they could have got their guns when they were drunk, but they were never given back unless the owners were perfectly sober.

In the spring of 1878, there was a big fight between Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad and the Denver & Rio Grande, to get possession of and hold the Grand Canyon of the Arkansas River where it comes out of the mountains just above Canon City, Colorado. Of course, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe folks came to Dodge City for fighters and gunmen. It was natural for them to do so, for wherein the whole universe were there to be found bitter men for a desperate encounter of this kind.

Dodge City bred such bold, reckless men, and it was their pride and delight to be called upon to do such work. They were quick and accurate on the trigger, and these little encounters kept them in good training. They were called to arms by the railroad agent, Mr. J. H. Phillips. Twenty of the brave boys promptly responded, among whom might be numbered some of Dodge’s most accomplished sluggers and bruisers and dead shots, headed by the gallant Captain Webb. They put down their names with a firm resolve to get to the joint in credible style in case of danger. The Dodge City Times remarks:

“Towering like a giant among smaller men was one of Erin’s bravest sons, whose name is Kinch Riley. Jerry Converse, a Scotchman descendant from a warlike clan, joined the ranks of war. There were other braves who joined the ranks, but we are unable to get a list of their names. We will bet a ten-cent note they clear the track of every obstruction.”

Which they did in creditable style. Shooting all along the line, and only one man hurt! This does seem marvelous, for the number of shots fired, yet the record is true of the story I am about to relate.

This was one of the most daring and dangerous shooting scrapes that Dodge City has ever experienced, and God knows, she has had many of them.

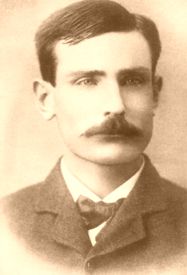

James Masterson

It seems that Peacock and James Masterson, a second brother of Bat, ran a dance hall together. For some reason, Masterson wanted to discharge their bar-keeper, Al Updegraph, a brother-in-law of Peacock, which Peacock refused to do, over which they had serious difficulty; and James Masterson telegraphed his brother, Bat, to come and help him out of his difficulties. I expect he made his story big, for he was in great danger if the threats had been carried out. Bat thought so, at least, for he came at once, with a friend.

Soon after his arrival, he saw Peacock and Updegraph going toward the depot. Bat holloed to them to stop, which I expect they thought a challenge, and each made for the corner of the little calaboose across the street. Bat dropped behind a railroad cut, and the ball opened; and it was hot and heavy, for about ten minutes, when parties from each side of the street took a hand. One side was firing across at the other, and vice versa, the combatants being in the center. When Updegraph was supposed to be mortally wounded and his ammunition exhausted, he turned and ran to his side of the street, and, after a little, so did Peacock, when Bat walked back to the opposite side and gave himself up to the officers.

The houses were riddled on each side of the street. Some had three or four balls in them; and no one seemed to know who did the shooting, outside of the parties directly concerned. At first, it caused great excitement, but the cooler heads thought discretion was the better part of valor, and, as both parties were to blame, they settled the difficulties amicably, and Bat took his brother away with him. Both parties displayed great courage. They stood up and shot at each other until their ammunition was exhausted. Though all did not contribute directly to the population of Boot Hill, there were many deeds of violence committed in Dodge City’s first ten years of life, that paralleled any which added a subject for interment in that primitive burying ground.

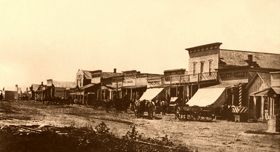

Dodge City in the late 1800s

Such a case was the shooting of Dora Hand, a celebrated actress. The killing of Dora Hand was an accident; still, it was intended for a cold-blooded murder, so was accidental only in the victim that suffered. It seems that Mayor James Kelly and a wealthy cattleman’s son, who had marketed many thousand head of cattle in Dodge during the summer, had a drunken altercation. It did not amount to much at the time, but, to do the subject justice, they say that Kelly did mistreat Kennedy. Anyhow, Kennedy got the worst of it. This aroused his half-breed nature. He quietly went to Kansas City, bought him the best horse that money could secure, and brought him back to Dodge. In the meantime, Mr. Kelly had left his place of abode, on account of sickness, and Miss Dora Hand was occupying his residence and bed.

Kennedy, of course, was not aware of this. During the night of his return or about four o’clock next morning, he ordered his horse, went to Kelly’s residence, fired two shots through the door, and rode away without dismounting. The ball struck Miss Hand in the right side under the arm, killing her instantly. She never woke up.

Kennedy took a direction just opposite his ranch.

The officers had reason to believe who did the killing but did not start in pursuit until the afternoon. The officers in pursuit were Sheriff Masterson, Wyatt Earp, Charles Bassett, Duffy, and William Tilghman, as intrepid a posse as ever pulled a trigger. They went as far as Meade City, where they knew their quarry had to pass, and went into camp in a very careless manner. In fact, they arranged to throw Kennedy off his guard completely, and he rode right into them when he was ordered three times to throw up his hands. Instead of doing so, he struck his horse with his quirt when several shots were fired by the officers, one shot taking effect in his left shoulder, making a dangerous wound. Three shots struck the horse, killing him instantly. The horse fell partly on Kennedy, and Sheriff Masterson said, in pulling him out, he had hold of the wounded arm and could hear the bones crunch. Not a groan did Kennedy let out of him, although the pain must have been fearful. And all he said was, “You sons of b—-, I will get even with you for this.” Under the skillful operation of Drs. McCarty and Tremaine, Kennedy recovered after a long sickness. They took four inches of the bone out, near the elbow. Of course, the arm was useless, but he used the other well enough to kill several people afterward, but finally met his death by someone a little quicker on the trigger than himself. Miss Dora Hand was a celebrated actress and would have made her mark should she have lived.

Meade, Kansas

One Sunday night in October 1883, there was a fatal encounter between two negroes, Henry Hilton and N***er Bill, two as brave and desperate characters as ever belonged to the colored race. Some said they were both struck on the same girl, and this was the cause.

Henry was under bonds for murder, of which the following are the circumstances. Negro Henry was the owner of a ranch and a little bunch of cattle. Coming in with many white cowboys, they began joshing Henry, and one of them attempted to throw a rope over him.

Henry warned them he would not stand any such rough treatment if he was a n***er. He did this in a dignified and determined manner. When one rode up and lassoed him, almost jerking him from his horse, Henry pulled his gun and killed him. About half of the cowboys said he was justifiable in killing his man; it was self-defense, for if he had not killed him, he would have jerked him from his horse and probably killed Henry.

Negro Bill Smith was equally brave and had been tried more than once. They were both found, locked in each other’s arms (you might say), the next morning, lying on the floor in front of the bar, their empty six-shooters lying by the side of each one. The affair must have occurred sometime after midnight, but no one was on hand to see the fight, and they died without a witness.

Mysterious Dave Mather

T. C. Nixon, the assistant city marshal, was murdered by Dave Mather, known as “Mysterious Dave,” on the evening of July 21st, 1884. The cause of the shooting was on account of an altercation between the two on the Friday evening previous. In this instance, it is alleged, Nixon had fired on Mather, the shot taking no effect.

On the following Monday evening, Mather called to Nixon and fired the fatal shot. This circumstance is mentioned as one of the cold-blooded deeds, frequently taking place in frontier days. And, as usual, to use the French proverb for the cause, “Search the woman.”

A wild tale of the plains is an account of a horrible crime committed in Nebraska, and the story seems almost incredible. A young Englishman, violating the confidence of his friend, a ranchman, is found in bed with the latter’s wife. This continued for some months until, in the latter part of May 1884, one of the cowboys, who had a grievance against Burbank, surprised him and Mrs. Wilson in a compromising situation and reported it to the woman’s husband, whose jealousy had already been aroused. At night, Burbank was captured while asleep in bed, by Wilson and three of his men, and bound before he had any show to make resistance.

After shockingly mutilating him, Burbank had been stripped of every bit of clothing and bound on the back of a wild bronco, which was started by a vigorous lashing. Before morning, Burbank became unconscious and was unable to tell anything about his terrible trip.

He thinks the outrage was committed on the night of May 27th, and he was rescued on the morning of June 3rd, which would make seven days that he had been traveling about the plains on the horse’s back, without food or drink, and exposed to the sun and wind. Wilson’s ranch is two hundred miles from the spot where Burbank was found, but it is hardly probable that the bronco took a direct course, and, therefore must have covered many more miles in his wild journey. When fully restored to health, Burbank proposed to make a visit of retaliation on Wilson, but it is unknown what took place.

The young man was unconscious when found, and his recovery was slow. The details, in full, of the story, would lend credence to the tale, but this modern Mazeppa suffered a greater ordeal than the orthodox Mazeppa.

Dodge City, Kansas 1876

This story is vouched for as true, and it is printed on these pages as an example of plains’ civilization.

“Odd characters” would hardly express the meaning of the term, “bad men” — the gun shooters of the frontier days; and many of these men had a habitation in Dodge City. There was Wild Bill, who was gentle in manner; Buffalo Bill, who was a typical plains gentleman; Cherokee Bill, with too many Indian characteristics to be designated otherwise; Prairie Dog Dave, uncompromising and turbulent; Mysterious Dave, who stealthily employed his time; Fat Jack, a jolly fellow and wore good clothes; Cock-Eyed Frank, credited with drowning a man at Dodge City; Dutch Henry, a man of passive nature, but a slick one in horses and murders; and many others too numerous to mention; and many of them, no doubt, have paid the penalty of their crimes.

Several times, in these pages, the “deadline” is mentioned. The term had two meanings in early Dodge phraseology. One was used in connection with the cattle trade; the other referred to the deeds of violence which were so frequent in the border town and was an imaginary line, running east and west, south of the railroad track in Dodge City, having particular reference to the danger of passing this line after nine o’clock of an evening, owing to the vicious character of certain citizens who haunted the south side. If a tenderfoot crossed this “dead” line after the hour named, he was likely to become a “creature of circumstances”; and yet, there were men who did not heed the warning, and took their lives in their own hands.

“Wicked Dodge” was frequently done up in prose and verse, and its deeds atoned for in extenuating circumstances; but in every phase of betterment the well being was given newspaper mention, for it is stated: “Dodge City is not the town it used to be. That is, it is not so bad a place in the eyes of the people who do not sanction outlawry and lewdness.” But Dodge City progressed in morality and goodness until it became a city of excellent character.

Even the memory of the wild, wicked days will soon be effaced, but, as yet, when one recounts their wild stories and looks upon the scenes of that wildness and wickedness, one can almost fancy the shades of defunct bad men still walking up and down their old haunts and glaring savagely at the insipidity of their present civilized aspect. The “Denver Republican” expresses a similar thought in a certain short poem, thus:

The Two-Gun Man

The Two-Gun Man walked through the town,

And found the sidewalk clear;

He looked around, with ugly frown,

But not a soul was near.

The streets were silent.

Loud and shrill,

No cowboy raised a shout;

Like panther bent upon the kill,

The Two-Gun Man walked out.

The Two-Gun Man was small and quick;

His eyes were narrow slits;

He didn’t hail from Bitter Creek,

Nor shoot the town to bits;

He drank, alone, deep draughts of sin,

Then pushed away his glass

And silenced was each dance hall’s din,

When by the door he’d pass.

One day, rode forth this man of wrath,

Upon the distant plain,

And ne’er did he retrace his path,

Nor was he seen again;

The cowtown fell into decay;

No spurred heels pressed its walks;

But, through its grass-grown ways, they say,

The Two-Gun Man still stalks.

Compiled and edited by © Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Robert M. Wright

Author and Notes: The Beginnings of Dodge City was written by Robert M. Wright in 1913. The article was Chapter seven of his book, Dodge City, The Cowboy Capital, and the Great Southwest: In The Days Of The Wild Indian, The Buffalo, The Cowboy, Dance Halls, Gambling Halls, And Bad Men (now in the public domain.) The article is not 100% verbatim, as minor grammatical and spelling corrections have been made. Wright came west from Maryland at the age of 16, first settling in Missouri. Later he worked as a freighter and became a trader at Fort Dodge. He then settled in Dodge City, known as a farmer, stockman, merchant, and politician. He served as Dodge City’s postmaster, the city’s first mayor, and later represented Ford County in the Legislature for four terms.

Also See:

Dodge City – A Wicked Little Town