The Salem, Massachusetts Witchcraft Hysteria – Legends of America (original) (raw)

“The Witch” depicts the use of The Pillory to enforce Puritan Morality in Colonial New England, 17th Century

Salem Witch Trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. Despite being generally known as the “Salem Witch Trials,” the preliminary hearings in 1692 were actually conducted in several towns across the province, including Salem Village (now Danvers), Ipswich, Andover, and Salem Towne. The Court of Oyer and Terminer conducted the most infamous trials in 1692 in Salem Towne.

People of the Witchcraft Trials:

The Persecuted Proctor Family of Peabody

Reverend Francis Dane of Andover

Procedures, Courts & Aftermath

Timeline of the Salem Witchcraft Events

The New England Puritans

Puritans. By George Henry Boughton, 1884

The Puritans of New England were a significant group of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who had grown discontent with the Church of England. They contended that The Church of England had become a product of political struggles and man-made doctrines and beyond reform. Escaping persecution from church leadership and the King, they came to America.

Before the Witch Trials, the Puritans were floundering about, trying to find a purpose. Until about 1660, most “Americans” had a common goal of working together to forge a new frontier; however, after the Puritan colony was well established, attention turned to gain, materially and spiritually. The Puritan colonists did not care for the English political leaders. Instead, they idolized the founding fathers, like those who came over on the Mayflower. However, by 1692, the founding fathers were dead and gone. Most of the population was initially born in England, but over the years, the tide changed, and in the late 1600s, America was filled with people born on her soil.

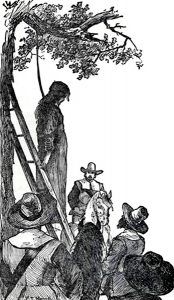

A woman hanged

There was no separation between church and state, and people who did not attend meetings were suspect and could be punished. Many towns had a rule that a man could not vote if he was not a church member. Because lying was considered a sin, it was punishable by law. Hangings were not common, but it was a form of entertainment that young children were encouraged to attend when one occurred. The most popular part of the hanging was the last words when the person about to be executed would say goodbye to his or her family. Puritans reasoned allowing children to witness hangings would teach them the consequence of immoral behavior.

Life was an exhausting array of chores with little amusement. The average family made their own bread, butter, cider, ale, clothes, candles, and just about everything else they used. Every member of the family could expect to work from morning to night. Houses were dark, damp, and depressing. Even in the middle of the day, a candle was always burning because the tiny windows let in so little light.

Most people could not write and signed their names on legal papers with their “mark.” Signing an “X” was unfashionable to young girls (and even grown women), who liked to make curly cue hearts and other inventive designs. Because most people couldn’t read, they didn’t care (or know) how their name was spelled, and since the court reporter couldn’t very well ask an illiterate person how to spell his or her name, the spelling depended on who was taking the notes. Many of the official documents spell individual names differently. Mary Easty was also Esty, Osborn, Osburn, Cory, Corey, etc. Even learned and educated men used loose grammar and did not worry about proper spelling.

Normal families had 5-10 children of their own, and it was not uncommon to have an extra child living in the home. By seven, children were given their full share of responsibility and expected to perform to adult standards. During this time, New England had one of the lowest infant mortality rates in America. Nine out of ten infants born there survived until age five, and perhaps three-quarters lived to see adulthood. In more rural areas, as many as 25% of children died before the age of one, and only about half made it to adulthood.

Most marriages ended with the early death of a spouse. A couple was lucky to get seven years out of each other. Second and third marriages were common. The man was the head of the household. A woman might offer her opinion to her husband behind closed doors and even prove a valuable ally, but she was expected to concede to her husband in all matters. She could not own property without her husband’s permission or vote. It was assumed that women were the weaker sex in every way, and if she did not follow her husband’s rules, he was encouraged to use physical abuse as a form of “correction.”

Salem was never attacked, but there was a real fear of Indians, especially due to an orphan from Maine who had watched his parents killed by Indians.

Puritan Beliefs

Puritan Hearthstone

For the Puritan people, the Bible was the law. It was taken literally, and sins like adultery and sodomy could be punished by death. During this time, the Puritan faith had been taking some blows, and because few new people were joining the ranks, ministers were constantly preaching about the falling ranks and the rise of the devil. These same ministers commonly spoke of the virtue of being a good wife, which was all a woman could really hope to be. A woman would be frowned upon if she owned her own land, didn’t have many children, or was in any way outspoken or different. In the meantime, many people dabbled in the occult and practiced white magic. Simple wives’ tales like fortune-telling were passed down from generation to generation. However, it was considered evil, and ministers often preached about the dangers of inviting the devil in through the occult.

There was also a general distrust and suspicion at the time. For instance, if a cow suddenly died, its owner would likely think one of his neighbors had cursed him. A man would not dare to question God’s judgment; he just questioned it being aimed at him. If he searched his soul and found he had done nothing to deserve the death of his cow, he would blame the misfortune on the devil acting through a witch. To deny God was unquestionable, so, by the same token, to deny the devil’s existence would be just as blasphemous. The Bible was a complete truth, and men who could read would consult the Bible for personal and legal matters.

Puritan Woman

The Puritan lifestyle was stringent and righteous, and they were not the loving and forgiving type one might expect in such a religious community. According to Marion Starkey, a 20th Century author, and historian, if a man had a toothache, the Puritans figured he had sinned with his tooth in some way. This feeling was so strong that some of the accused witches confessed in bewilderment and wracked their brains to find something they had done in the past to allow the devil to use them in such a manner. The Puritans used fasting to honor God and unite the community for various causes, even though meals were significant and usually the only time in the day when a person could sit and relax for a moment.

To the Puritans, there was little separation between dreams and real life – there is a reason for everything, believing that dreams contained prophesies, revelations, and truths that were more real than daily life.

Politics

Massachusetts was a colony of England, and was forced to run things according to a set of rules, called a “Charter,” handed down from the English king. However, getting word to England would take ten weeks by ship. In March 1692, when the first “witch scare” broke out, the previous charter had been long eliminated. This meant there was no leader, no rules, and the nearest thing to a leader was in England negotiating for a new charter. Because of the situation, the accused witches were examined and held in jail but not tried. In May, Increase Mather, a Puritan minister involved with the colony’s government and the administration of Harvard College, sailed back from England with a new charter and governor. This was when the actual trials began.

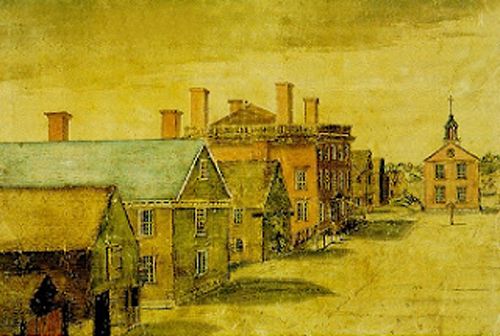

Salem Village

Salem Village, Massachusetts

All his life, Thomas Putnam, a resident of Salem Village, had been resentful of rich families, like the Porters, the richest family in the village. Both families grew up in Salem Towne, but the merchant Porters were more worldly and successful than the farming Putnams. No matter how hard he tried, Thomas Putnam, an influential man in his own right, just felt he couldn’t measure up to the Porters, who had more land and money. What really bothered Thomas Putnam was that the Porters were considered smarter than the Putnams because they were better-spoken. As a result, Thomas set out to break away from Salem Towne and form Salem Village, but the township wasn’t eager to let the property go.

Salem Village was allowed to build a meeting house, but it was to act as a franchise of the Salem Towne meeting house. Thomas Putnam tried to pull rank by handpicking the ministers, but this only served to divide the community in half; those who supported Putnam and his choice of a minister and those who hated Putnam wouldn’t support any choice he made. Ultimately, all the unsuspecting ministers, who were sometimes not even paid, would eventually leave Salem Village because of the conflict.

Salem Village was finally allowed to act independently, and Samuel Parris was the first minister to hold the job for the budding community.

The Witch, According to the Salem Puritan

There were many beliefs among the Puritans about what constituted a “Witch.” They thought that witches were notorious for killing otherwise healthy infants and that they had pets, known as “familiars,” to do their evil bidding. The familiars would drink the blood of their witch masters from an extra “teat” located somewhere on its body, usually near the genitals, and having the particular habit of sucking between the index and middle finger.

Witches were also thought to be able to “curse” those who had irritated them. They were also believed to have made a pact with the devil and could not say the “Our Father” prayer without making mistakes.

The Afflicted

In Salem Village in the winter months of 1691-92, 9-year-old Elizabeth “Betty” Parris, and her cousin Abigail Williams, age 11, the daughter and niece (respectively) of Reverend Samuel Parris and his wife Elizabeth, began to have fits. The girls screamed, threw things about the room, uttered strange sounds, crawled under furniture, and contorted themselves into peculiar positions. The girls complained of being pinched and pricked with pins. Village doctor, William Griggs, was called, and he could find no physical evidence of any ailment and gave his opinion that the girls were victims of witchcraft. John Hale, a minister in nearby Beverly, described their condition as “beyond the power of Epileptic Fits or natural disease to effect.”

Betty Parris was the first to claim her illness was due to being “bewitched.” Their contortions, convulsions, and outbursts of gibberish at first baffled everyone, especially when other girls began to show similar symptoms. After Betty Parris and Abigail Williams, 12-year-old Ann Putnam, Jr. also began to show strange behavior signs. Shortly after her illness, the Salem witch trials began, with the girls accusing neighbors of witchcraft.

The Accused

The first three people accused and arrested for allegedly afflicting Betty Parris, Abigail Williams, Ann Putnam, Jr., and Elizabeth Hubbard were Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba. The accusation by Ann Putnam, Jr. is seen by historians as evidence that a family feud may have been a major cause of the Witch Trials. Salem Village was the home of a vicious rivalry between the Putnam and Porter families, and most residents were somehow engaged in this rivalry. It was so bad that Salem Village citizens often engaged in heated debates that would escalate into full-fledged fighting.

Sarah Good was a homeless beggar accused of witchcraft because of her appalling reputation. At her trial, she was accused of rejecting the puritanical expectations of self-control and discipline when she chose to “torment and scorn children instead of leading them towards the path of salvation.” Sarah Osborne rarely attended church meetings and was accused of witchcraft because the Puritans believed that she had her own self-interests in mind. The residents of Salem Village also found it distasteful when she attempted to control her son’s inheritance from her previous marriage. Tituba was a slave of a different ethnicity than the Puritans and an easy target for accusations. She was accused of attracting young girls like Abigail Williams and Betty Parris with enchanting stories of sexual encounters with demons, swaying the minds of men, and fortune-telling, which stimulated the imaginations of young girls.

All three of these women were seen as outcasts and fit the description of the “usual suspects” for witchcraft accusations. No one stood up for them, and they were brought before the local magistrates and interrogated for several days, starting on March 1, 1692. Afterward, they were sent to jail, and numerous other accusations followed.

Martha Corey, Dorcas Good, and Rebecca Nurse of Salem Village, and Rachel Clinton of nearby Ipswich were soon accused. Martha Corey had voiced skepticism about the credibility of the girls’ accusations, drawing attention to herself. The charges against her and Rebecca Nurse deeply troubled the community because both were full church members. Dorcas Good, the daughter of Sarah Good, was only four-years-old, and when questioned by the magistrates, her answers were construed as a confession, implicating her mother. In Ipswich, Rachel Clinton was arrested for witchcraft at the end of March on charges unrelated to the girls’ afflictions in Salem Village.

The First Examination

Examination of a witch

Sarah Good was brought out first. She adamantly denied hurting the girls and indicated she thought Sarah Osborne might be a witch. Then, Sarah Osborne was brought forth, denying any role in the afflictions. She was the first accused to point out that the devil could use her likeness without permission, but this did not sway the judges. During the questioning of both of these women, the “afflicted girls” would scream in agony, go into trances, and copy every movement Good and Sarah Osborne made.

Tituba came out last. At first, she denied harming the girls, claiming she loved Betty and would never hurt her, but the “afflicted girls” were screaming that Tituba was hurting them at that very moment.

Soon, Tituba realized her claims of innocence were falling on deaf ears and changed her story. She began to tell the shocked audience about late-night broomstick trips with Good and Osborne, familiars in the shape of yellow birds, a grotesque animal with the head of a woman, and most alarming, a tall, male witch leader from Boston who carried with him the devil’s book, which had at least nine signatures. However, Tituba couldn’t read who they were.

She described how the devil tempted her with “pretty things” and how Good and Osborne pressed her to hurt the girls. Tituba’s confession had several consequences; it lent credibility to the girls, but more importantly, it scared the wits out of everyone present. Even the “afflicted girls” remained silent while Tituba wove her story. The villagers were dismayed to realize the witch problem was bigger than they had imagined and set about trying to find the seven witches who had made their mark in the tall man from Boston’s evil book.

The Afflictions Intensify

Afflicted Girl

To all who saw, the fits seemed genuine. At one point, a girl who was not named claimed to be watching the specter of a ghost wrapped in a white sheet float about the crowded room. Her father snatched into the air in the direction she pointed and mysteriously produced a torn piece of sheet. Events like this cause present-day historians to assume the afflictions were not only faked but facilitated by adults who knew they were fake. Because of his bad reputation, most people assume the girl and father in this story are Ann and Thomas Putnam, but the record does not mention names.

The “afflicted girls” were a scary and convincing sight, bleeding, rigid, contorted, crying, and screaming out in agony. Some would lay there comatose, and others would writhe around on the floor. They became experts at embellishing each other’s stories. One fearful night, the whole congregation was huddled together in terror, believing hundreds of invisible witches were surrounding the meetinghouse peering in through the windows all around them. The action wasn’t limited to the meetinghouse, and suspicious events began to happen throughout Salem. People would search for a lost broom to find it sitting high in a tree. The heightened fear added to the chaos, and everything seemed to carry an ominous note. The whole town was gripped with fear of a demonic invasion.

The afflicted were always being poked, pinched, or bitten by specters, and they had the marks to prove it. Blood flowed freely, and bruises were common. As a rudimentary test, bite marks on the afflicted were compared with the accused’s bite, and it always seemed to match up, even if the accused had no teeth. More and more girls began to join the circle of the afflicted and even some grown women. We can never be sure if this was an honest case of mass hysteria, a ploy for attention, or a subconscious outcry to the constrictions placed upon women. What is known is that once one girl said something, the other girls, backed by their parents, would chime in and embellish the story.

It can be difficult to ascertain who did what, particularly at examinations and trials, because there was no official stenographer. Notes were taken by many people, quite often the Reverend Samuel Parris, and the records tend to lump the afflicted as “the girls” or “the afflicted.” Of all the girls afflicted, only two lived with both their parents. Abigail Williams was a constant voice among the afflicted from the beginning until the end.

Mercy Lewis was an active witchfinder from the start. She eventually gave birth to an illegitimate child. Long after the trials, when people discussed the “afflicted girls,” Mercy would be used as an example to discredit them and suggest they were nothing more than trollops looking for attention. Elizabeth Hubbard was an orphaned servant girl working for her own aunt and uncle. According to records, “She is notable for remaining in a trance for an unusually long time: the whole of the Elizabeth Proctor’s examination.” Mary Walcott was said to have spent most of the examinations knitting.

Mary Warren, John and Elizabeth Proctor’s servant girl, had a brief moment of sanity when she tried to recant after the Proctors were arrested. But, when Abigail Williams said Mary had signed the devil’s book and Mary herself was accused of being a witch, she quickly decided she would rather be afflicted and slipped back into her fits. Susanna Sheldon was nothing if not inventive. In less than two weeks, she was allegedly bound and gagged by spirits four times, though a neighbor was always handy to untie her.

It wasn’t just young girls who were “afflicted.” Mrs. Bathshua Pope was an older woman who joined in with the accusers after Tituba’s confession. Her affliction permitted her to mouth off publicly, complaining when sermons went on too long and throwing objects across the room at accused witches. Goody Bibber was an older woman known about town for gossip and ill will. Her actual name was Sarah Bibber, but at that time, the Puritan community had a class system. A married woman of respect was referred to as “Mrs.” or “Goodwife,” while women of a lesser class were referred to as “Goody.” While she did not have a bad reputation because of a checkered past, most people in town did not like her and would rather avoid her. More than once, folks complained that Goody Bibber could go into fits “whenever she pleased.” During the witch hysteria, she was mentioned in depositions and testimony against 15 people accused of witchcraft.

Specter of a Puritan “Witch”

Ann Carr Putnam, Sr., the mother of Ann Putnam, Jr., also went in and out of fits. She was the first to accuse Rebecca Nurse. Ann had long struggled with nightmares of her dead sister. In her dreams, Ann’s sister and her deceased children would appear to be trying to tell her something important, but Ann couldn’t understand them. She mentioned this to others about town, and it was well known that Ann Sr. thought someone had not only cursed her family but caused the death of most of the young children. To Ann, there was simply no other explanation for the family’s high casualty rate.

What Happened to the Accused:

The “afflicted girls” would say a person’s “shape” was torturing them, a warrant was issued, and the accused would be taken into custody. The accused would then be checked over for the witch’s mark by a group of people of the same sex. The mark was usually found somewhere near the genitals (quite often between the vagina and the anus). Having a questionable mark was bad enough, but if it was pricked with a pin and did not bleed, it was damning evidence.

The accused was brought in front of the girls for an examination, and the “afflicted” would immediately fall into fits. Typically, they would claim the accused person’s “shape” was sitting on the beam near the ceiling. Sometimes there was also an animal, usually a yellow bird sucking between the index and middle finger. Sometimes an invisible man was whispering into the ear of the accused. The suspected “witch” would naturally deny this, throwing their hands up and rolling their eyes, but the “afflicted girls” would copy every movement to the extreme as if they couldn’t control their own movements.

The girls would be bleeding from their mouths or other parts of their bodies. One girl even had a pin stuck through both her lips. Some were found tied and hung up on hooks. The whole area was gripped with a heightened red alert, and everything had an ominous tone. All anyone talked about was “the poor afflicted girls” and how evil took hold of them. The Puritans hated nothing more than the devil. In their minds, they were warriors for God, and they aimed to win the battle in His name. If the learned and respected ministers and magistrates thought the devil was afflicting these poor young children, it must be so. The fits would intensify when an accused claimed innocence, and the “touch test” would be employed. The Puritans believed if a witch touched an afflicted girl, the witch’s spirit would be forced to return to her body. If the fit ceased at the accused’s touch, it was taken as direct evidence of guilt.

Once accused of being a witch, the best option seemed to be a confession. Some people confessed, hoping to spare their lives, while others confessed because they genuinely thought they might have done something to invite the Devil to use their form. Once a witch confessed, she was expected to name her accomplices, and there was no use saying there was no accomplice. Though there was some talk of hanging the confessing witches after they were no longer needed to testify, all those who confessed escaped execution.

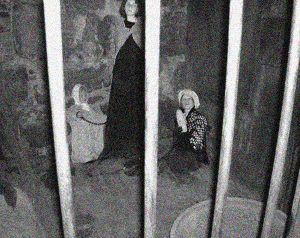

Witch Dungeon Museum

The accused would then be taken to jail, where they would be chained and held to await trial. People were responsible for paying for their own jail costs, down to the chains used to hold them. Even after they were cleared, some had to stay in jail because they couldn’t afford the jailor’s bill.

A tactic commonly employed was “tying neck to heels,” a throwback from Old England. The neck and the back of the heels were tied together, forcing the body into a nauseating backward hoop. This treatment was not only reserved for charged criminals. Children of the accused witches were commonly tortured to make them give damaging information about their families. A person could be kept in this way for as much as 24 hours, but, like everything else, the level of trauma inflicted depended upon the individual interrogator.

The families of the accused had different reactions. Some washed their hands of their kin, believing them witches. Others, like Rebecca Nurse and her sisters, always stood by their family, maintaining their innocence, but were powerless to do anything to stop the madness. Other families begged their loved ones to confess whether they were witches. Family members had to be careful because they could be charged as witches if they protested too much.

When the accused were brought to trial, they didn’t stand a chance. Everyone was found guilty of the first 19 witches and sentenced to death. One more was pressed to death because he refused to make a plea. The hangings were a public event. The accused would travel by cart, with people running alongside, taunting and cursing. Then, one by one, they would climb a ladder, say their last words, and the ladder would be taken out from under them. Because there was no sharp fall to break the neck, it could take as many as ten minutes to die. After the hanging, their bodies were thrown in a shallow common grave near the site (some told stories of arms and legs sticking out of the hole). Some families, like Rebecca Nurse, snuck back to the gravesite during the night to remove the body and bury it in a secret place.

Witch Hysteria Ends

People began to turn away from the trials when they witnessed the heartfelt last words of those being hanged, but the real ending started when important people began to be accused. Some of these included Margaret Thatcher, who was the mother-in-law of Magistrate Jonathan Corwin, who presided over the examinations from the very first; former Governor Simon Bradstreet’s sons, Colonel Dudley Bradstreet and John Bradstreet of Andover; Sarah Noyes Hale, the wife of popular Beverly minister, John Hale; and Lady Mary Phips, the wife of the sitting governor, William Phips.

On October 12, 1692, the Massachusetts General Court held a meeting to determine what to do about the situation. They decided to forbid further imprisonment for witchcraft. On October 26, Massachusetts’ church leaders called for a statewide day of fasting, hoping God would give them the answer to the witch problem.

Though the accusations were still coming in, the accused were now let out on bail instead of thrown into the overflowing jails. People were beginning to see the mistakes that had been made, and now, the leaders were trying to figure out how to stop them. They couldn’t very well pardon all of the witches and admit to putting 20 innocent people to death, but they couldn’t, in good conscience, allow the trials to continue. The questions continued for another four months while 150 accused sat in jail. Finally, all accused witches were discharged and released from prison in May as long as their jail costs were paid.

After many petitions, in October 1710, The General Court reversed all convictions against those who had a family to ask. Bridget Bishop, Susannah Martin, Alice Parker, Ann Pudeator, Wilmot Redd, and Margaret Scott were not cleared because they didn’t have a family to petition on their behalf. On December 17, 1711, the families of the executed witches were given the sum of 578 pounds and 12 shillings to be distributed among 24 relatives of the accused witches.

What Happened To…

The Reverend Samuel Parris tried to keep his job in Salem Village; but, Rebecca Nurse and Sarah Cloyce’s friends and relatives eventually got rid of him. His wife, Elizabeth, died in 1696, and the following year, he left the village. He was replaced by Joseph Green, who succeeded in smoothing over many of the divisions within the community and congregation. Parris then when to Stowe, once again arguing over the terms of his employment. He lasted there only a year. He later remarried and died in 1720.

Some of the “afflicted girls” — Betty Parris, Elizabeth Booth, Sarah Churchill, and Mercy Lewis all married. No one knows what became of Abigail Williams, Elizabeth Hubbard, Susanna Sheldon, or Mary Warren.

Ann Putnam, Jr. never married. Her parents died in 1699, Thomas at 46 and Ann, Sr. at 37. Ann Putnam, Jr. was left to care for her nine younger brothers and sisters. At the age of 26, she wrote a formal apology read to the congregation by the new minister, Joseph Green. She said, “I justly fear I have been instrumental, with others, though ignorantly and unwittingly, to bring upon myself and this land the guilt of innocent blood…As I was a chief instrument of accusing Goodwife Nurse and her two sisters, I desire to lie in the dust and to be humbled for it.” Ann grew into a sickly woman and died at 37, like her mother.

By Krista Delle Femine, with additional edits by Kathy Alexander/LegendsOfAmerica, updated January 2023.

Also See:

The Salem Witchcraft Hysteria Timeline

On May 9, 1992, the Salem Village Witchcraft Victims’ Memorial was dedicated in Danvers, Massachusetts.

Sources:

Aronson, Marc. Witch-Hunt: Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials. New York: Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2003.

Hanson, Chadwick. Witchcraft at Salem. New York: George Braziller, 1969.

Hill, Francis. A Delusion of Satan. New York: Doubleday, 1995.

History.org, US. “Puritan Life.” 2009`. Us History Online Textbook. 13 May 2009.

Jack Tager, Richard D. Brown. Massachusetts: A Concise History. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1978.

Kamensky, Jane. The Colonial Mosaic: American Women 1600-1760. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Knappman, Edward W. Great American Trials: From Salem Witchcraft to Rodney King. Detroit: Visible Ink, 1994.

Sewall, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Sewall. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Inc., 1973.

Starkey, Marion. The Devil in Massachusetts. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1949.

Wilson, Lori Lee. How History is Invented: The Salem Witch Trials. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Company, 1997.

About the Author: Krista Delle Femine, from Hyannis, Massachusetts, attended school at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, receiving her Associate’s Degree. She has five sons, a daughter, and triplet grandsons. She plans to continue her education and become a lawyer. About herself, she says she loves to learn and teach and that she hopes to pay her blessings forward by passing on what she has observed and learned. She also describes herself as a curious wanderer who intends to live her life with an open mind and noble heart in the hopes that her children will follow in her footsteps. This story contains additional information and edits by Legends Of America’s Founder/Editor Kathy Weiser-Alexander.