Mining in the Rocky Mountain West – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Mining Tipple, Gold Hill, Nevada by Carol Highsmith, 2022.

Within 15 years of the gold discoveries in California, there was more exploration and settlement in hundreds of valleys scattered over the Rocky Mountain West. The men who exploited California had generally been amateur miners, acquiring skill through bitter experience. However, a professional class made the subsequent developments, which permeated into the most remote recesses of the mountains in Colorado, Nevada, Arizona, Idaho, and Montana. Activity was constant during these years all along the continental divide. New camps were being born overnight, and old ones were abandoned just as quickly. Here and there, cities rose and remained to mark success in the search. Abandoned huts and half-worked diggings were scars covering a fourth of the continent.

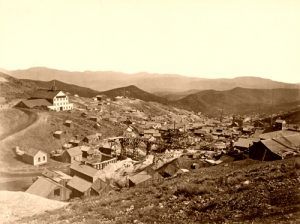

Gold Hill, Nevada, by Timothy O’Sullivan, 1867.

Colorado, in the summer of 1859, attracted the largest migrations, but while Denver was being settled, a boom began farther west, which outdid it in significance. The old California Trail from Salt Lake City, Utah, crossed the Nevada desert and entered California by various passes through the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Several trading posts had been planted along this trail by Mormons and others during the 1850s until 1854, when the legislature of Utah created Carson County at the west end of the territory to benefit the settlements along the Carson River. Small discoveries of gold were enough to draw a floating population that founded Carson City as early as 1858 to this district. But there were no indications of great excitement until after finding a marvelously rich silver vein near Gold Hill in present-day Nevada in the spring of 1859. Here, not far from Mount Davidson but a few miles east of Lake Tahoe and the Sierras, was the famous Comstock Lode, upon which it was possible to build a state within five years.

The California population, already rushing about from one boom to another in perpetual prospecting, seized eagerly upon this new district in western Utah. The stage route by way of Sacramento and Placerville, California, was crowded beyond capacity while hundreds marched over the mountains on foot. “There was no difficulty in reaching the newly discovered region of boundless wealth,” asserted a journalistic visitor. “It lay on the public highway to California, on the state’s borders. The tide of emigration poured in from Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska, from Pike’s Peak and Salt Lake. Transportation from San Francisco was easy. Carson City had existed before the great discovery. Virginia City, named for a renegade southerner nicknamed “Virginia,” soon followed it while the typical population of the mining camps piled in around the two.

In 1860, miners came from a larger area. The new Pony Express ran through the heart of the fields and aided in advertising them east and west. Colorado was only one year ahead in the public eye. Both camps obtained their territorial acts within the same week, that of Nevada receiving President James Buchanan’s signature on March 2, 1861. All of Utah west of the 39th meridian from Washington became the new territory, which, through the need of the union for loyal votes, gained its admission as a state in three more years.

Carson Valley, Nevada, by Kathy Alexander.

The rush to Carson Valley drew attention away from another mining enterprise further south. In the western half of New Mexico, between the Rio Grande and the Colorado Rivers, there had been successful mining ever since the acquisition of the territory. The southwest boundary of the United States after the Mexican-American War was defined in words that could not be applied to the face of the earth. This fact, together with the knowledge that an easy railway grade ran south of the Gila River, had led in 1853 to the purchase of additional land from Mexico and the definition of a better boundary in the Gadsden treaty. In these lands of the Gadsden Purchase, old mines came to light in the years immediately following.

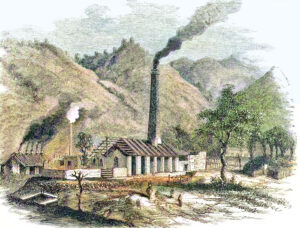

Sylvester Mowry and Charles D. Poston were most active in promoting the mining companies that revived abandoned claims and developed new ones near the old Spanish towns of Tubac and Tucson, Arizona. The region was too remote, and life was too hard for the individual miner to have much chance. Organized mining companies here replaced the detached prospectors of Colorado and Nevada. Disappointed miners from California came in, and perhaps “the Vigilance Committee of San Francisco” did more to populate the new Territory than the silver mines. Tucson became the headquarters of vice, dissipation, and crime… It was a paradise of devils. Excessive dryness, long distances, and Apache depredations discouraged rapid growth. Yet, the surveys of the early 1860s and the passage of the overland mail through the camps in 1858 advertised the Arizona settlement and enabled it to live.

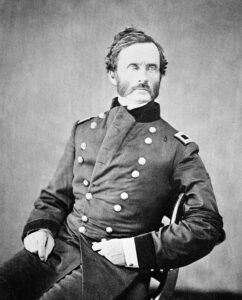

Colonel James H. Carleton.

The outbreak of the Civil War extinguished the Mowry mines and others in the Santa Cruz Valley for a time, holding them in check until a second mineral area in western New Mexico could be found. United States army posts were abandoned, Confederate agents moved in, and Indians became bold. The federal authority was not established until Colonel James H. Carleton led his California column across Colorado and through New Mexico to Tucson early in 1862. During the next two years, he maintained his headquarters at Santa Fe, New Mexico, carried on punitive campaigns against the Navajo and the Apache, and encouraged mining.

The Indian campaigns of Carleton and his aides in New Mexico aroused much controversy. There were no treaty rights by which the United States had privileges of colonization and development. It was forcible entry and retention, maintained in the face of bitter opposition. With Kit Carson’s assistance, Carleton waged a war of scarcely concealed extermination. He told Washington they understood “the direct application of force as a law. If its application is removed, it becomes lawless at that moment. This has been tried over and over and over again and at great expense. The purpose now is never to relax the application of force with a people that can no more be trusted than you can trust the wolves that run through their mountains; to gather them together little by little, onto a reservation, away from the haunts, and hills, and hiding-places of their country, and then to be kind to them; there teach their children how to read and write, teach them the arts of peace; teach them the truths of Christianity. Soon, they will acquire new habits, new ideas, and new modes of life; the old Indians will die off and carry with them all the latent longings for murdering and robbing; the young ones will take their places without these longings and thus, little by little, they will become a happy and contented people.”

Mowry Silver Mine, Arizona.

At the start, Carleton had seized Mowry’s mines as tainted with treason. The whole Tucson district was believed to be so thoroughly in sympathy with the Confederacy that the commanding officer was much relieved when rumors came of a new placer gold field along the left bank of the Colorado River around Bill Williams Creek. However, the population of the territory moved as fast as it could. Teamsters and other army employees deserted freely. Carleton deliberately encouraged surveying and prospecting and wrote personally to General Halleck and Postmaster-General Blair, congratulating them because his California column had found the gold to suppress the Confederacy. “One of the richest gold countries in the world,” he described it to be, destined to be the center of a new territorial life and to throw into the shade “the insignificant village of Tucson.”

The population of the silver camp had begun to urge Congress to provide a territory independent of New Mexico immediately after the development of the Mowry mines. Delegates and petitions had been sent to Washington, D.C., in the usual style. But congressional indifference to new territories had blocked progress. The discoveries reopened the case in 1862 and 1863. Forgetful of his Indian wards and their rights, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs had told of the sad peril of the “unprotected miners” who had invaded Indian Territory of clear title. They would offer to the “numerous and warlike tribes” an irresistible opportunity. The territorial act was finally passed on February 24, 1863, while the new capital was fixed in the heart of the new goldfield at Fort Whipple, near which the city of Prescott soon appeared.

Camp Grant, Arizona.

The erection of a territorial government did not end the Indian danger in Arizona. There never came a population large enough to intimidate the tribes, while bad management from the start provoked needless wars. Most serious were the Apache troubles, which began in 1861 and ceased only after General George Crook’s campaigns in the early 1870s. In this struggle occurred the massacre at Camp Grant in 1871, when citizens of Tucson, with careful premeditation, murdered in cold blood more than 80 Apache men, women, and children. The degree of provocation is uncertain, but the disposition of Tucson, as Mowry phrased it, was not such as to strengthen belief in the justice of the attack: “There is only one way to wage war against the Apache. A steady, persistent campaign must follow them to their haunts—hunting them to the ‘fastnesses of the mountains.’ They must be surrounded, starved into coming in, surprised, or inveigled—by white flags or any other method, human or divine—and then put to death. If these ideas shock any weak-minded individual who thinks of himself as a philanthropist, I can only say that I pity him without respecting his mistaken sympathy. A man might as well sympathize with a rattlesnake or a tiger.”

The mines of Arizona, though handicapped by climate and inaccessibility, brought life into the extreme Southwest. Those of Nevada worked the partition of Utah. Farther to the north, the old Oregon country gave out its gold in these same years as miners opened up the valleys of the Snake and the headwaters of the Missouri River. Right on the crest of the continental divide appeared the northern group of mining camps.

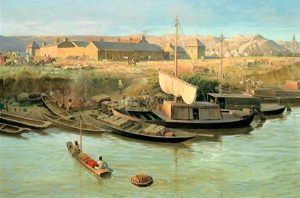

Old Fort Benton, Montana by John Ford Clymer, 1967.

The territory of Washington had been cut away from Oregon at its request and with Oregon’s consent in 1853. It had no significant population and was the subject of no agricultural boom as Oregon had been. Still, the small settlements on Puget Sound and around Olympia were too far from the Willamette country for convenient government. When Oregon was admitted as a state in 1859, Washington was made to include all the Oregon country outside the state, embracing the present Washington and Idaho, portions of Montana and Wyoming, and extending to the continental divide. The overland trail ran from Fort Hall, Idaho, almost to Walla Walla, Washington. Because of its urging, Congress built a new wagon road passable by 1860 from Fort Benton, on the upper Missouri River, to the junction of the Columbia and Snake Rivers. Farther east, the American Fur Company’s active business had in 1859 established steamboat communication from St. Louis, Missouri, to Fort Benton so that an overland route to rival the old Platte Trail was now available.

In eastern Washington, the most important of the Indians were the Nez Perce, whose peaceful habits and friendly disposition had been noted since the days of Lewis and Clark and who had permitted their valley of the Snake River to become a main route to Oregon. Treaties with these had been made in 1855 by Governor Isaac Stevens, by which most of the tribe were in 1860 living on their reserve at the junction of the Clearwater and Snake Rivers and were reasonably prosperous. Here, as elsewhere, was the specific agreement that no whites except government employees should be allowed in the Indian Country. However, in the summer of 1861, the news that gold had been found along the Clearwater River brought the agreement to naught. Gold had been discovered the summer before. In the spring of 1861, pack trains from Walla Walla brought a horde of miners east over the range, while steamboats soon found their way up the Snake River. In the fork between the Clearwater and Snake Rivers was a good landing where, in the autumn of 1861, sprang up Lewiston, Idaho, named in honor of the great explorer, acting as the center of life for 5,000 miners in the district and showing by its very existence on the Indian reserve the futility of treaty restrictions in the face of the gold fever. The troubles of the Indian department were significant. “To attempt to restrain miners would be, to my mind, like attempting to restrain the whirlwind,” reported Superintendent Kendall.

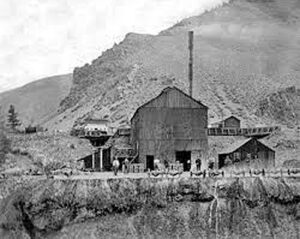

Idaho Mine.

“The mines on the Salmon River have become a fixed fact and are equaled in richness by few recorded discoveries. Seeing the utter impossibility of preventing miners from going to the mines, I have refrained from taking any steps which, by certain want of success, would tend to weaken the force of the law. At the same time, I carefully avoided giving any consent to unauthorized statements and verbally instructed the agent in charge that, while he might not be able to enforce the laws for want of means, he must give no consent to any attempt to lay out a town at the juncture of the Snake and Clearwater Rivers, as he had expressed a desire of doing.”

Continued developments proved that Lewiston was in the center of a region of unusual mineral wealth. The Clearwater River finds were followed closely by discoveries on the Salmon River, another tributary of the Snake River, a little farther south. The Boise mines came on the heels of this boom, followed by a rush to the Owyhee District, south of the great bend of the Snake. The usual flood of miners from the whole West poured into these various camps. Before 1862 was over, eastern Washington had outgrown the boundaries of the territorial government on Puget Sound. Like the Pike’s Peak diggings, the placers of the Colorado Valley, and the Carson and Virginia City, Nevada camps, these called for and received a new territorial establishment.

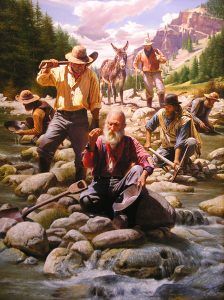

Gold Seekers by Alfredo Rodriquez.

In 1860, the territories of Washington and Nebraska met along a common boundary at the top of the Rocky Mountains. Before Washington was divided in 1863, Nebraska had changed its shape under the pressure of a small but active population north of its seat of government. The population centers in Nebraska north of the Platte River were chiefly represented by overflows from Iowa and Minnesota. Emigrating from these states, farmers had by 1860 opened the country on the left bank of the Missouri River, in the region of the Yankton Sioux. The Missouri River traffic had developed both river shores past Fort Pierre, South Dakota, and Fort Union, North Dakota, to Fort Benton, Montana, by 1859. To meet the needs of the scattered people here, Nebraska was partitioned in 1861 along the line of Missouri and the 43rd parallel. Dakota had been created out of the country and thus cut loose, and in two years, more shared in the fate of eastern Washington. Idaho was established in 1863 to provide home rule for the miners of the new mineral region. It included a great rectangle on both sides of the Rockies. It reached south to Utah and Nebraska, west to its present western boundary at Oregon and 117°, east to 104°, the eastern line of Montana and Wyoming. Dakota and Washington were cut down for its sake.

In 1862 and 1863, it seemed as though every little creek in the mountain country possessed its treasures to be given up to the first prospector with the hardihood to tickle its soil. Four important districts along the upper course of the Snake River, not to mention hundreds of minor ones, lent substance to this appearance. Almost before Idaho could be organized, its settlement area had broadened enough to make its division a certainty soon. East of the Bitter Root Mountains, in the headwaters of the Missouri River tributaries, came a long series of new booms.

When the American Fur Company pushed its little steamer Chippewa up to the vicinity of Fort Benton in 1859, none realized that a new era for the upper Missouri River had nearly arrived. For half a century, the fur trade had been followed in this region and had dotted the country with tiny forts and palisades, but there had been no immigration and no reason for any. The Mullan Road, which Congress had authorized in 1855, was in the course of construction from Fort Benton to Walla Walla, but as yet, there were few immigrants to follow the new route. However, before the territory of Idaho was created, the active prospectors of the Snake Valley had crossed the range. They inspected most of the Blackfeet country in the direction of Fort Benton. They had organized for themselves a Missoula County, Washington Territory, in July 1862, an act which may be taken as the beginning of an entirely new movement.

Alder Gulch, Montana.

Two brothers, James and Granville Stuart, were the leaders in developing new mineral areas east of the main range. After experience in California and several years of life along the trails, they settled in the Deer Lodge Valley and began opening up their mines in 1861. They accomplished little this year since the steamboat to Fort Benton, carrying supplies, was burned, and their trip to Walla Walla for shovels and picks took up the rest of the season. But early in 1862, they were hard and thriving at work. Reinforcements destined for the Salmon River mines farther west came to them in June; one party from Fort Benton and the other from the Colorado diggings were easily persuaded to stay and organize Missoula County. Bannack City became the center of their operations.

Alder Gulch and Virginia City were, in 1863, a second focus for the mines of eastern Idaho. Their deposits had been found by accident by a prospecting party that was returning to Bannack City after an unsuccessful trip. The party, which had been investigating the Big Horn Mountains, discovered Alder Gulch between the Beaver Head and Madison rivers early in June. With an accurate knowledge of the mining population, the discoverers organized the mining district and registered their claims before revealing the location of the new diggings. Then came a stampede from Bannack City, which gave Virginia City a population of 10,000 by 1864.

Another mining district, in Last Chance Gulch, gave rise in 1864 to Helena, the last of the great boom towns of this period. Its situation and resources aided Helena’s growth, which lay a little west of the Madison fork of the Missouri River and in the direct line from Bannack and Virginia City to Fort Benton. Only 142 miles of easy staging above the head of Missouri River navigation was a natural post on the main line of travel to the northwest fields.

Bannack Montana. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

The excitement over Bannack, Virginia City, and Helena overlapped in years during a similar boom in Idaho. It had begun even before Idaho had been created. When this was once organized, the same inconveniences justified it and its division to provide home rule for the miners east of the Bitter Root range. An act of 1864 created Montana territory with the state’s boundaries today, while that part of Idaho south of Montana, now Wyoming, was temporarily reattached to Dakota. Idaho assumed its present form. The simultaneous development of rich mining camps in all portions of the great West did much to attract public attention and population.

In 1863, nearly all of the camps flourished. The mountains were occupied for the whole distance from Mexico to Canada, while the trails were crowded with emigrants hunting for fortune. As usual, the old trails bore much of the burden of migration, but new spurs were opened to meet new needs. In the north, the Mullan Road had made easy travel from Fort Benton to Walla Walla and had been completed since 1862. Congress authorized in 1864 a new road from eastern Nebraska, which should run north of the Platte trail, and the war department had sent out personally conducted parties of emigrants from the vicinity of St. Paul. The Idaho and Montana mines were accessible from Fort Hall, the former by the old emigrant road, the latter by a new northeast road to Virginia City. The Carson mines were on the main line of the California Trail. The Arizona fields were commonly reached from California by way of Fort Yuma.

The shifting population that inhabited the new territories invites and, at the same time, defies description. It was made up chiefly of young men. Respectable women were not unknown but were so few that they had little measurable influence on social life. In many towns, they were in the minority, even among their sex, since the easily won wealth of the camps attracted dissolute women who cannot be numbered but who must be imagined. The preponderance of men determined the social tone of the various camps, the absence of regular labor, and the speculative fever that justified their existence. The nature of the population determined the political tone, the character of the industry, and the remoteness of a seat of government. Combined, these factors produced a life that America had never known and whose picturesque qualities blinded the thoughtless into believing it was romantic. It was at best a hard bitter struggle with the dark places only accentuated by the tinsel of gambling and adventure.

Idaho Mining Camp.

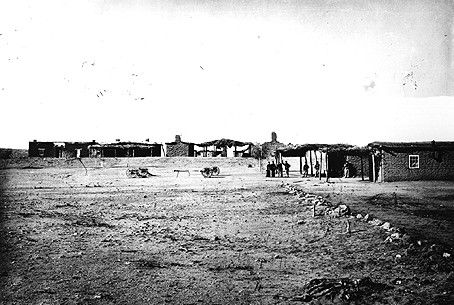

The typical mining camp was a single street meandering along a valley, with one-story huts flanking it in irregular rows. The saloon and the general store, sometimes combined, were its representative institutions. Deep ruts along the street bore witness to the heavy wheels of the freighters, while horses loosely tied to all available posts at once revealed the regular means of locomotion, and by the careless way they were left about showed that this sort of property was not likely to be stolen. The mining population centered here lived a life of contrasts. The desolation and loneliness of prospecting and working claims alternated with the excitement of coming to town. Few decent beings habitually lived in the towns. The resident population expected to live off the miners, either in the way of trade or worse. The bar, the gambling house, and the dance hall have been made too familiar in description to need further account. In the reaction against loneliness, the extremes of drunkenness, debauchery, and murder were only too frequent in these places of amusement.

That the camps did not destroy themselves in their frenzy is a tribute to the solid qualities that underlay the recklessness and shiftlessness of much of the population. In most of the camps, there came a time when decency finally asserted itself as the only possible way to repress lawlessness. The rapidity of these camps had drawn hundreds and thousands into the territories’ fastnesses and carried them beyond the limits of ordinary law and regular institutions. Law and the politician followed fast enough, but there was generally an interval after the discovery during which such peace prevailed as the community demanded. In the absence of a sheriff and constable and a jail in which to incarcerate offenders, the vigilance committee was the only protection of the new camp. Such summary justice as these committees commonly executed is evidence of innate tendency toward law and order, not of their defiance. The typical camp passed through a period of peaceful exploitation at the start, then came an era of invasion by hordes of miners and disreputable hangers-on, with accompanying violence and crime. Following this, in its stern repression of a few crudest sins, the vigilance committee begins a reign of law.

New home in the Far West.

The mining camps of the early 1860s familiarized the United States with the whole area of the nation and dispelled most of the remaining tradition of desert, which hung over the Mountain West. They attracted a large floating population, secured the completion of the political map through the erection of new territories, and loudly emphasized the need for national transportation on a larger scale than the trail and the stagecoach could permit. However, they did not directly secure the presence of a permanent population in the new territories. Arizona and Nevada lost most inhabitants when the first flush of discovery was over. Montana, Idaho, and Colorado declined rapidly to a fraction of their largest size. None of them successfully secured a large permanent population until agriculture had gained a firm foothold. Many who came to mine remained to plow, but the permanent populating of the Far West was the work of railways and irrigation two decades later. Yet the mining camps had served their purpose in revealing the nature of the national domain.

Source: Paxson, Frederic L.; Last American Frontier, The MacMillan Company, New York, 1910. Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, May 2024.

Also See:

Military Campaigns of the Indian Wars