Burning of Osceola – Newspaper Accounts – Legends of America (original) (raw)

The following is a historic news text from when the Missouri town of Osceola found itself in the ruins of the Civil War. For the story of this historic city, see our article Osceola, Missouri – Surviving All Odds

Quick background: After the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, on August 10, 1861, the Union army retreated, leaving the Kansas border exposed. General James H. Lane organized his men to combat this and led them into action against a Confederate general, Sterling Price, in the Battle of Dry Wood Creek on September 2, 1861. Though his troops lost the battle, Lane continued fighting and pillaging in Papinville, Butler, Harrisonville, and Clinton, Missouri, before coming to Osceola on September 23, 1861. At that time, Osceola was a prosperous town of over 2,000 people, though most of its able-bodied men were off to war.

Lingering fury regarding the resulting Osceola Massacre stirred hatred in many a Missouri citizen. It would become one of the causes for William Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence, Kansas, two years later, on August 21, 1863.

Here is how the story played out in some of the newspapers at the time:

Osceola Burned by General Lane – New York Times, October 1, 1861

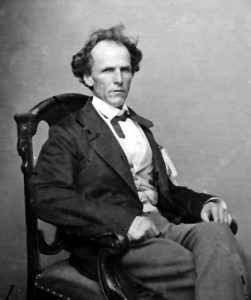

General James H. Lane

Jefferson City, Saturday, September 28

A gentleman who arrived here this morning from the West states he saw a gentleman who passed through Osceola on Wednesday last, who says that General Lane had burned the central portion of that town. It is stated the reasons for burning were that the rebels had fired on our troops from windows. No National troops were near there when he left.

General Lane’s Success at Osceola – New York Times, October 5, 1861

From the Leavenworth Conservative, September 28th.

From O.A. Bassett, Esq., who arrived yesterday from Fort Scott, we learn that General Lane has been completely successful in his forced march upon Osceola.

After his victory in Papinville, already recorded, he proceeded immediately to Osceola in St. Clair County, Missouri, a distance of 20 miles.

The rebel force there was dislodged, the town burned to the ground, and the immense supply train of Rains and Price was captured.

This train was between two and three miles long, containing all the supplies and equipment of Rains and Price and $100,000 in money. This is the most important success gained for the Union cause in Missouri and goes far to redeem our losses at Lexington. Lane is now on his way back, and they may soon be expected in this vicinity.

McCulloch is still near Fort Scott, and his men swear they are bound for Kansas.

Correspondence of the Missouri Democrat: Headquarters Kansas Brigade – New York Times, October 14, 1861

Additional From Kansas City, October 3, 1861

I furnish you with the facts in this communication so that your readers may be correctly informed concerning General Lane’s march upon Osceola. Information was received that the rebels had left many army stores in Osceola, that General Price had been repulsed from before Lexington, and that, in all probability, he would be in full retreat in a few days. The object of the expedition was to cut off the enemy’s retreat, to seize his stores, and to attend to any other business along the route which the cause might demand. It was also reported that the enemy had assembled in force at Papinsville and one or two other places along the line of our contemplated march.

The advanced column, consisting of infantry, cavalry, and artillery, left camp on the evening of September 17, under Colonel James Montgomery’s command, with the intention of surprising the enemy at Papinsville at daybreak the next morning. But he had vamoosed the ranch, and on our arrival, only a few families were left, and these were the rankest kind of Unionists.

As we moved, nothing important occurred until we came to the Sac River, five miles west of Osceola. Here, Mr. Harris, formerly a Quartermaster in the rebel army, was trying to raise a force to prevent our crossing. General Rains had burned the fine bridge at this point early in the season, and this is the only place at which the stream is fordable for many miles.

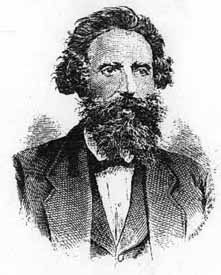

Colonel James Montgomery.

Colonel Montgomery was too quick for him, and the rebel Harris became our prisoner. We reached Osceola a little after night set in and, through a mistake of the guide, got upon the suburbs of the town before we were aware of it. As our advance under Colonel Weir’s command was moving along the road, a heavy fire was opened upon it from the bushes nearby. The veterans halted and returned the compliment. The enemy fired again by which their position was better understood; our men then gave him fire from successive platoons. He fired a third line and fled, leaving 14 dead and wounded upon the field, or rather in the bush. Whilst our men were still in position, another volley was poured into them from a nearby log house. Captain Moonlight turned upon them his howitzer, which soon routed the rebels, and fired the building. On our side, two men were slightly wounded. No other casualties occurred. The missiles of the enemy passed from one to four feet over our heads. The behavior of Colonel Weir and of his command was as cool and brave as could be desired.

Our men slept upon their arms that night, and the first object that met their eyes in the morning was the succession flag floating over the courthouse. This, in itself, was enough to condemn that temple of justice to destruction. Still, in addition, all appearances indicated that the rebels had turned it into a fortification to be used in the defense of treason and traitors. Captain Moonlight’s howitzer dispatched its missile of destruction against it, and soon, the building was a heap of ruins. Slowly and carefully, our men then advanced upon the town, but the enemy had fled, and the fighting part of the expedition was at an end. An examination was then made of the character of the town. A large quantity of lead, some powder, army clothing, and provisions were found. All our wagons were loaded to their utmost capacity, and the order was given to return to camp. Colonel Weir favored sparing the rebel town, but the counsel of Colonels Montgomery and Richey prevailed, and the business portion thereof was committed to the flames. The reasons for its destruction were:

- It was traitorous to the core – but one loyalist could be found in it.

- It was a place of general rendezvous for the enemy.

- He intended to make of it a military post during the Winter.

- It was naturally a strong position and could be easily fortified.

- if left standing the enemy would return as soon as our army left.

- The Government could not afford to make such expeditions every few weeks.

- We hoped to draw the enemy back from the Missouri River upon us and give the rebels generally the benefits of the terror of our arms.

Loyal citizens along the route rejoiced at the approach of our army. Many of them breathed freely for the first time in the last few months. The rebel army and its marauding bands have been a scourge to all that section of Missouri. The people have been bled and plundered till they have but little left. Mothers have seen the clothing stripped from their children before their eyes. Several families improved the opportunity our army afforded to leave the State. Western Missouri has but few inhabitants left, and thousands of acres of corn will be left in the field un-gathered. Not a field of fail-sown wheat did I notice in our long march. The rebellion seems to have brought an accumulation of all the curses upon the great State of Missouri. And the end is not yet. We have probably seen but the beginning of sorrows. If the authors of this rebellion could endure but a little of the suffering they have brought upon the people, they would cry out in the language of another – “The pains of hell have got hold of us.”

General Lane’s brigade was constantly in motion and successful in every undertaking. However, the loss of Lexington and his summons to Kansas City thwarted all his plans.

We are now in camp awaiting General Fremont’s orders to attack the rebel army in or near Lexington.

Missouri Campaign.

The Campaign In Missouri., etc. – New York Times, November 9, 1861 (Excerpt)

From Our Special Correspondent, Camp Brooks, Bolivar, Missouri, October 27, 1861

I closed my last letter to the Times at Fort Station, a point 12 miles above this on the Overland Road and 46 miles from Springfield. The night before last, General Sturgis, attended by a wild-looking body of men who, being mounted on horses, are, I suppose, entitled to the name of cavalry, came over. I was immensely glad to see the old veteran and readily accepted an invitation to sit in his carriage and cross over to visit his command.

Soon, we were traveling swiftly over the smooth prairies in the luxurious General Sturgis vehicle. A journey of eight miles brought us to a little town named Humansville, on the road leading from Osceola to the Overland Road. We drove up in front of a white house of Moderate respectability when the noise of our carriage brought to the door a gentleman of middle age, in his stocking feet and wrapped in a gray military overcoat.

“General Lane,” said General Sturgis, and in a moment thereafter, I was shaking hands heartily with General Jim Lane — a more noted, more feared, more hated, more talked-of man does not exist in Missouri or any other state. Two minutes later, the two Generals were in a hot discussion — Sturgis claiming that the government is to make itself felt as to its foes, conciliate the wavering and reward its friends — in general, not to steal indiscriminately. General Lane agreed to this, but he combated the other’s arguments with smooth sophistry. In contrast, he seemingly agreed with him. He alluded, with a humorous twinkle in his eye and a pleasant laugh at the fun of the thing, the reminiscence of negroes stolen, houses burned, citizens robbed, and prisoners shot after compelled to dig their own graves. He asserted that he had forbidden, under penalty of death, stealing on the part of his troops.

“Yes, exactly, but didn’t your men steal $8,000 from Mrs. Vaughn at Osceola?” General Sturgis asked, ” And didn’t they take even the clothes of old Stringer’s grandchild?”

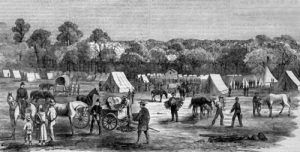

General Jim Lane’s camp, near Humansville, MO, October 1861, by Alexander Simplot.

General Lane’s eyes twinkled with fun as these interesting memories were called to his mind. With an “I grant you my fellows have done some wrongs!” and a laugh of infinite gusto, he changed the subject and smilingly proceeded to discuss another part of the matter in question.

After a short conversation, I left him armed with the following document:

“Colonel Montgomery: Receive Mr. ______, report of the New York Times, kindly. — Lane”

Proceeding a short distance below the town, I came upon Lane’s encampment and, after a little, succeeded in getting speech with a man in citizen’s dress — Colonel Montgomery. I presented my credentials, shook an emaciated hand, and then dropped down on a pile of tents to have a chat. He waxed eloquent upon the emancipation of the negro and his hope of a millennium at hand, in which they would gain political and social equality with the white man. I will give only one of his remarks.

“If our boys thought that this war had any other object than to give freedom to the slave, they would everyone go home tomorrow.”

All through Western Missouri, I found a deadly terror entertained towards Lane and Montgomery, possibly for a good reason. The day before yesterday, Lane sent back to Kansas 100 negroes, and this morning, as his train passed, I counted 102 more of these ebony chattels. Everywhere that he has been, he carries the torch and the knife with him and has left a track marked with charred ruins and blood.

An old man told me his story, — told it with composure, while he said that they had taken his horses, mules, grain, his wife’s dresses, and then fired the log shanty that afforded his gray hairs shelter from the pelting rain and the nipping frosts. He told all this in detail with a firm voice, but when he added, “They even stole the clothes of my little dead grandson,” his lip trembled convulsively a moment, and then the hot tears gushed from his eyes and found ready channels down his time-furrowed cheeks.

At Osceola was a family named Vaughn — a man and his wife — wealthy, young, educated, refined, and respectable. Vaught took up arms for the South, received a commission as captain, bug gave himself up to Lane and was released on parole. When Lane passed through Osceola, he burned the beautiful residence of Vaughn to the ground, then followed the family to a log house in the country where they had fled, and there, upon the information of a salve, dug up $8,000, which they had buried, sacked the house, taking seven silk dresses and all the valuables belonging to Mrs. Vaughn, and then left.

I learned of a dozen other similar cases, which would be mere repetition.

The Raid of Osceola, September 21, 1861 – Memphis Daily Appeal, April 13, 1862

Illustration of the Sacking of Osceola, published in “The Border Outlaws” by James W. Buel, 1880.

Editors Appeal: I have been requested by several friends to publish a statement of facts that occurred at Osceola of which I had personal knowledge. At first, I deemed it unadvisable, but on reading an article in the Appeal about the conduct of the Federal troops at Nashville, their pretended kindness and consideration to the people there, and the evident motive thereof, I determined to send to your paper a simple account of my experience of their wanton cruelty and insult when policy holds forth no inducement for hypocrisy.

I have further confirmed this resolution by examining Andrew Johnson’s speech then. It is right that a few startling truths should meet his mass of falsehoods. Read what he says of the friendly intention of our invaders, and then all I shall tell you of their treatment, of what they call a conquered province, and judge what your fate will be when the chains they are forging shall be clasped around you.

Perhaps the people of the South who have heard of the raid of Osceola have wondered what should have given to this remote little village such importance in the eyes of the Kansas robbers as to make it the object of an expedition, in which, they acknowledge, three thousand men and two pieces of artillery were engaged. In the first place, it was a stronghold of men who had risen en masse whenever their forays called for protection to the border, and they had long threatened its destruction. Then, when South Carolina boldly proclaimed the old Union null and void, in consequence of Northern violation of all its sacred obligations and the selection of a sectional candidate for the presidency, who publicly declared that “the irrepressible conflict” should be the most important part of the program of his administration, the citizens of this place raised one of the first secession banners that floated in the air of Missouri, and companies formed there were among the first to enlist in the holy cause.

The ladies were untiring in their zeal and were busy night and day in completing tents and clothing for the soldiers of their own and other counties. All this gave it the notoriety of rebellion, which was used as an excuse to cover the other and more powerful motives that induced the raid. Like Captain Dalgetty, the promise of good pay was heard when the call of patriotism was unheeded. Our merchants had large and rich assortments of goods, which were freely exchanged with the State troops for scrip, for the issue of which the Legislature had given no sanction. A branch bank was established here, and its glittering heaps were a great temptation. Colonel Snyder of the State army had a cartridge factory in the suburbs in operation. When General Price moved up from Springfield to Lexington, some ammunition was sent to Osceola for safekeeping until called for. All these things were well known to Lane and Montgomery, as we afterward discovered that the latter was in constant correspondence with a woman in our midst, a Yankee, it is true, but one whom we had considered a lady.

The first intimation of danger was a threatened attack from the Union rabble of Thomasville, a Black Republican town near us. All of our men who were not in the army banded together, keeping watch day and night, and this and the opportune arrival of Captain Landis and a company on their way to Price saved us from that demonstration. Hardly had that cloud passed by when the news came that the regular Kansas jayhawkers were marking on us with a force of about 5,000 men. We had no defense against them. A little company of 36 men under Captain Weidemeger was all the opposing force left us. The specie of the bank, the papers, etc., were hastily concealed; $90,000 of the specie about my residence did not make me feel very comfortable. The negroes of the town and neighborhood were sent with provisions to the woods; a few goods were hidden, and then as the alarm of their advance came nearer, the few gentlemen left, among whom were the bank officers, sought refuge in the thick growth around the place.

At about 3 o’clock in the night, we, the defenseless women and children, heard the first reports of their firearms mingled with those of the brave little band of 36 who fired at the foe from behind an old building as they neared the town. The contest against such odds was short, of course, though 40 of their number were killed, as one of their officers and several of their privates acknowledged. A pause, and then the cowards, fearful of advancing on the unprotected town, commenced a cannonading, which endangered the lives of the females and children who were its only garrison.

A Rebel Prowler Shooting a Union Picket near Jefferson City, Missouri, sketched by James A. Guirl.

By sunrise, they had satisfied themselves that they might make the venture and poured in. Then commenced the pillage. The stores were broken into and rifled; their Union brethren, of whom I am thankful to say there were but few, called to share in the robbery. The unlicensed soldiers seized on the whisky first and soon became so ungovernable that the officers ordered the destruction of what remained of that article. The rude outlaws entered the dwellings, demanding of the ladies their sentiments, “North or South? and commanding an answer. I, for one, was glad of the opportunity to declare myself separate and distinct from all sympathy with such a band of thieves, and they certainly heard no complimentary words from the ladies of Osceola that day. The torch was applied as soon as they had taken all they desired. Amid the shrieks of the frightened women and children and the roaring of the first kindled flames, they went on from the stores to the bank, which had been left open, even the safe, to prevent its destruction; to our church, which was destroyed with laughing words and blasphemous jests, and then to the private dwellings. Lastly, the courthouse, with all the records, was set on fire because, they said, secession soldiers had sheltered there. The houses of my two sons, one of whom was absent in the army, and my daughter was consumed among the rest. Mine was in the suburbs and fortunately escaped.

I was very uneasy about the money, but although they searched other residences, mine was overlooked. Our barn, filled with grain and hay, was burnt, and a soldier approached the house with a torch but was prevented by Montgomery from applying it. Just then, a panic seized them. They heard a rumor that General Slack’s division of State troops was advancing from Warsaw, and pell-mell obeyed the hurried order to retreat with their ill-gotten booty. Quickly, every trace of their presence, except the run they left behind, had disappeared, and we thought we should be at peace again. But soon, we heard a noise behind our smokehouse, and ongoing thither found a Federal soldier seated on a powerful horse, flourishing his revolver in a drunken, bravado manner. I spoke to him as calmly as I could and asked him what he wished for. “You have had a little fire here today, madam,” he said with an unfeeling laugh. I told him, “Yes, an outrage had been committed there, such as the civilized nations would shudder to hear of.”

“It is all right, madam,” he replied, “you deserve it all for your cursed rebellion,” I asked him again if he wished for anything. He said he wished I could tell him the shortest way to the Ford. I gave him the information required, and he turned off, rode by the backyard where my daughters and niece were sitting, threw his pistol forward, nearly in their faces, frightening them very much, and passed on to the front yard. I went to the front portico to watch the movements, fearing that he intended to set fire to the house. When he reached the gate, he placed two fresh caps on his pistol and, holding it up, called for me. I went with as brave a look as I could assume and asked why he called me to him. He intimated that the way to the Ford, which I had directed him to take, looked too much like an ambuscade and asked me to guard him through the thicket. I told him nothing could induce me to do so, showed him the broad road, and told him if he was afraid, he had better proceed in that direction. He paused a moment, then dashed down the brushy way to the river and, plunging in, swam his horse across, fearing to look for the ford. From this time until Fremont’s advance and final retreat, our men were too uneasy to stay often in their houses at night and lived like wild beasts more than human beings.

We heard of Lexington’s capture and hoped that our delivery was at hand. Then the news came that Price was forced, for want of caps, to retreat again towards the Arkansas line, and soon after that, Fremont was advancing with a powerful army. This was confirmed in a few days by the arrival of Lane’s division on the banks of the Osage River opposite Osceola.

A company of Delaware Indians, mounted and led by Lieutenant Johnson, plunged into the stream, and the gentlemen of our household had hardly leaped the palings into the thickets beyond the house, ere they had surrounded our dwelling and commenced their insulting search. You may imagine the effect produced by a band of whooping Indians, arrayed in wardress and paint, on unprotected women who had so lately passed through the terrors of their first visit. They found six good guns around the premises, some lead and bullets, and about sixty kegs of powder concealed in our carriage house, part of which belonged to our army. They also found nearly $10,000 in coin, which had been buried in the yard — our paper money of less value, we had about our persons. Lieutenant Johnson captured two of our negro men and forced them by threats of hanging, shooting, etc., to show them our farm teams, etc. The goods that had been saved from the burning, our flour supply, furniture, clothing, and jewelry, were there. The goods they distributed among their Union friends. The flour and clothing they bestowed on a train of negroes sent off in haste to Kansas. The furniture was broken up, the ladies’ bonnets, laces, jewelry, etc., stolen or wantonly destroyed. Even the books did not escape them but were torn up and scattered to the winds. A volume of Bancrofts United States, containing a portion of the history of the revolution, told too heavily against them and was reduced to fragments. Lieutenant Johnson then proceeded in his disgraceful work to yet lower depths of infamy by commencing a search through our house. No place was too sacred for him to invade, and with smiles and unfeeling remarks, he opened our family papers. Several letters from my soldier son to his father (but lately dead) he boastingly held up as proofs of treason by which to wrest from the widow and orphan all that robbery had left. These, with several from the Honorable Wald P. Johnson, abstracted for the same purpose, he refused to return to me, and when I applied to Lane, he endorsed the decision. I wondered if I were dreaming when I looked out from my window while this was going on and saw the stars and stripes, waving near, its once glorious folds, protecting and sanctioning the proceedings of desperadoes who had forgotten that a Constitution ever existed, which protected the liberties of the people.

This young lieutenant was scarcely advanced to manhood — so young and yet so old in wickedness. He belongs to a good family in Indiana, and his brother-in-law, who was evidently ashamed of his conduct, said he was astonished at his rapid march in evil and acknowledged that he would “not only steal but lie about it afterward.”

I must do the Jayhawkers the justice to say that some of their officers were respectful and kind to us, which is better than my experience of the “gentlemanly Sturgis” and his lawless troops, who came just after. We were kept in constant terror, however, by their threats against our absent sons, brothers, and friends. Several of the officers told me that Lane had sent the Indians out with orders to shoot them down wherever they were found. I went to his headquarters with my son’s wife, who was almost frantic, to learn the truth. He calmly told me it was so and advised me to send him word to give himself up, spicing his remarks and advice with oaths and curses against the rebels. He spoke against treason as if he had never been an attainted traitor, with Federal troops after him, when he made his famous run into Iowa.

When Lane, the leader of the van,

His swiftest soldier still outran.

When General Sturgis came, he denounced his illustrious compeer in unmeasured terms, and, at first, we thought him sincere. But before he left, we discovered the source of his indignation: he had been awakened to the knowledge that Lane was the more successful and profitable rogue. His soldiers were much more insulting than Lane’s and spared us neither curses nor threats of every evil. May God grant that I may never be placed in such brutal company again, where women’s purity and dignity were unrespected and where, for the first time, my cheek burned with shame that I had ever been a citizen under their disgraced banner. What does it cover now?

Oppression, wrong, and tyranny,

Cold-hearted thirst for anarchy,

Licentious passion, wild and free,

And shame’s disgusting brow.

Some of Lane’s officers deemed it their duty to protect the citizens who wished for it by placing a guard around their houses.

Terrified by the conduct of the soldiers under Sturgis, I rose from a sickbed to ask for a similar safeguard. Colonel Fuller, a member of the general’s staff, seemed much amused at my distress and application but promised to grant my request. But he never sent the guard and exposed us to fears worse than death during his stay in Osceola. This is a simple statement of some scenes that occurred at Osceola, during the ravages of the war in Southwest Missouri. I could add incident on incident, horror on horror. I could tell of the reign of blood and terror in Jackson County and other unfortunately exposed parts of the border, but this may surely suffice. Andrew Johnson knows all this, and yet he comes to his own State — a State that has honored and loved him — with the kiss of Judas to betray her. I hope the golden bribe of his treachery may Tarpeia like to crush him with its weight. As much as I have suffered, I would suffer on, even to death, rather than see my countrymen of the generous and chivalric South yield to the tender mercies of men like these. I pray that the tide of blood may soon be stayed by the establishment of the liberties of the Confederate States; otherwise, I would rather share in their annihilation than see them, vassals, to tyrants who ignore every honorable principle of civilized warfare and glory in rapine, murder, and robbery. If the voices from the desolation of Missouri could speak, the ruined fields, the rifled granaries, the brave men murdered, the women and children driven from burning homes in the rigor of winter, the violated sanctuaries of the living God, if these could speak, they would send trumpet tones of warning to those among us who weakly deem that submission may purchase immunity from all this wrong and degradation. Brethren of the South! Your hope lies in the justice of your cause, strong arms, brave hearts, and the God of battles.

Glory to them who die in this great cause,

Kings, bigots, can inflict no brand of shame,

Or shape of death, to shroud them from applause,

Their hangman fingers cannot touch their fame.

Though fortune waver, still there will be some

Proud hearts, the shrine of freedom’s vestal flame,

Long trains of ills may pass, unheeded, dumb,

But vengeance is behind, and justice is to come.”

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024. The text is not verbatim, as grammatical errors and spelling have been corrected, and it has been updated for the modern reader.

Also See:

Osceola, Missouri – Surviving All Odds

Lane’s Brigade, aka Kansas Brigade – Protecting the Free State

The Civil War (main page)