The Hopi – Peaceful Ones of the Southwest – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Hopi House in Arizona,

Primarily living on a 1.5 million-acre reservation in northeastern Arizona, the Hopi (peaceful ones) people have the longest authenticated history of occupation of a single area by any Native American tribe in the United States. Thought to have migrated north out of Mexico around 500 B.C., the Hopi have always lived in the Four Corners area of the United States.

Initially, they were a hunting and gathering group divided into numerous small bands that lived in pit houses. However, around the year 700 A.D., the Hopi became an agricultural people, growing blue ears of corn using runoff from the mesas. Many small bands began to come together at this time, and large villages began to be established atop the mesas, the first at Antelope Mesa, east of present-day Keams Canyon, Arizona. Masonry walls came into use, and aboveground dwellings replaced pit houses. As the population grew, agriculture became more and more important.

From 900 to 1100 A.D., many small masonry villages appeared. Subsequent drying of the climate over the next 200 years saw a clustering of the area’s population into larger villages, such as Oraibi, Awatovi, Wupatki, Betatakin, and the villages in Canyon De Chelly.

Men dressed in Kachina costumes.

At about this same time, the “Kachina Cult” began among the Hopi people. Though no one knows how it originated, there is evidence today of kachina art found in the Puerco Ruins in the Petrified Forest National Park that dates back to about 1150 A.D. and other evidence of kachina masks and dancers appearing in rock art around 1325 A.D.

Kachinas are the spirits of deities, natural elements or animals, or the deceased ancestors of the Hopi. Before each kachina ceremony, the village men will spend days studiously making figures in the likeness of the kachinas represented in that particular ceremony. The figures are then passed on to the village’s daughters by the Giver Kachina during the ceremony. Following the ceremony, the figures are hung on the walls of the pueblo and are meant to be studied to learn the characteristics of that certain Kachina.

By the 15th century, the culture of masked dancers and carved dolls were known to have become a part of the culture of various Puebloan tribes in the southwest. In the next century, the Spanish began to document having seen bizarre images of the devil hanging in Pueblo homes. These were most likely kachina dolls. The kachina practices and ceremonies continue to this day.

Hopi Indian bringing in the harvest, photo by the Detroit Publishing Company, about 1900

In the late 1200s, a massive drought forced 36 of 47 villages on the Hopi mesas to be abandoned. Following the drought, the 11 remaining villages grew, and three new villages were established in Northeastern Arizona, about 70 miles from Flagstaff. While the Hopi located their villages on mesas for defensive purposes, the land surrounding the mesas was also used by the tribe, dividing it between families and utilizing common areas for agricultural, medicinal, and religious purposes.

By the 16th century, the Hopi culture was highly developed, with an elaborate ceremonial cycle, complex social organization, and an advanced agricultural system. They also participated in an elaborate trade network that extended throughout the Southwest and into Mexico.

The Hopi society was matrilineal, with women determining people’s inheritance and social status. When a man marries, the children from the relationship are members of his wife’s clan.

The Hopi practice a complete cycle of traditional ceremonies, although not all villages retain or have the complete ceremonial cycle. These ceremonies occur according to the lunar calendar and are observed in each Hopi village. Like other Native American groups, the Hopi have been influenced by Christianity and the missionary work of several Christian denominations. Few have converted enough to Christianity to drop their traditional religious practices.

The Hopi enjoyed a peaceful way of life until the first outsiders arrived in the Hopi territory in 1540. Under the leadership of Don Pedro de Tovar, the Spanish were looking for the legendary Seven Cities of Gold. The Spaniards were not received with friendliness at first. Still, the opposition of the natives was soon overcome, and the party remained among the Hopi for several days, learning from them the existence of the Grand Canyon. When they were unsuccessful in the search for the precious metal, they returned to Mexico but continued to maintain sporadic contact.

Antelope priests chanting at Kisi Moki snake dance, Hopi, Detroit Photographic, 1902.

In 1592, the Spanish returned when Catholic priests established a mission at Awatovi. For the next nine decades, the priests would attempt to suppress the Hopi religion and convert the tribe to Catholicism.

The Hopi acquired horses, burros, sheep, cattle, and new fruits and vegetables introduced by the Spanish into their diet. The Spanish and later Europeans also introduced smallpox, which, over the centuries, periodically reduced the populations of the mesas from thousands to hundreds in devastating epidemics.

Pueblo Revolt.

In 1680, the Hopi joined the Puebloans of New Mexico in the Pueblo Revolt, which forced the Spanish out of the Southwest. Although the Spanish successfully re-conquered the pueblos, they could never firmly reestablish a foothold among the Hopi.

Following on the heels of the Spanish, the Navajo, who were also under pressure from the Europeans, began moving into Hopi territory in the late 1600s. Scattered throughout the area, they appropriated Hopi rangeland to graze their livestock, farm fields, and water resources and conducted frequent raids against Hopi villages. The peaceful Hopi were forced to battle for their survival in a long period of fighting that would last until 1824, when Spain recognized Mexico and the Hopi lands were given to the new Mexican government. Though no longer having to face the Spanish, the Navajo continued to attack the Hopi until they were forced onto reservations in 1864.

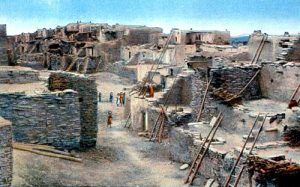

Hopi Pueblo.

In 1848, the United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe de Hidalgo, which changed the jurisdiction over the Hopi lands.

After the area became part of the United States, white settlers began to explore it in greater numbers, and in 1870, the U.S. government laid claim to the lands of the Hopi. Once again, the Hopi were forced to fight to save their lands until finally, they were forced onto the reservation in Black Mesa in 1882, where most still live today.

Once on the reservation, the U.S. government spent years attempting to eradicate the Hopi culture and religion. Children were made to go to school, men and boys were forced to cut their hair, and efforts to convert the Hopi to Christianity intensified. Ultimately, this resulted in the incarceration of Chief Lomahongyoma and eighteen other Hopi Indians being placed in Alcatraz for their resistance to the “forced culture.” From January 3 to August 7, 1895, the group was imprisoned for resisting to farm on individual plots away from the mesas and refusing to send their children to government boarding schools.

Hopi Pueblo by Edward S. Curtis, 1906

In 1934, a changing tide of sentiment toward Native Americans led to the Indian Reorganization Act, which codified the U.S. government’s obligations to protect and preserve Native Americans’ rights. Soon after, the Hopi Tribal Council was formed in 1936 to establish a single representative body of the Hopi with which the U.S. Government could do business.

Like other Native American tribes, the Hopi lands were drastically reduced, and their current reservation represents only 9% of their original landholdings. Originally, they occupied almost all of northern Arizona, from California to parts of southern Nevada. The Hopi Reservation in Black Mesa, Arizona, is surrounded by the Navajo reservation and is where most of the Hopi live today. However, a few Hopi live on the Colorado River Indian Reservation, on the Colorado River in western Arizona.

Today, the Hopi, more than most Native American peoples, retain and continue to practice their traditional ceremonial culture. They also continue to battle legally with the U.S. government and the Navajo tribe for the return of their native lands. Traditionally, the Hopi are highly skilled micro or subsistence farmers. The Hopi also are part of the broader cash economy; a significant number of Hopi have mainstream jobs; others earn a living by creating high-quality Hopi art, notably the carving of Kachina dolls, the expert crafting of earthenware ceramics, and the design and production of fine jewelry, especially sterling silver.

Today, the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona occupies some 1.5 million acres with several pueblos, most notably Walpi and Old Oraibi. Most villages are closed to their Kachina dances, but some social dances remain open to the public. Photography, sketching, and recordings are prohibited.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Hopi Weaving, 1879.

More Information:

Hopi Cultural Preservation Office

P.O. Box 123

KykoP.O.vi, Arizona 86039

928-734-2441.

Also See:

Ancient Puebloans of the Southwest

Sources: