The Mandan – Friends of the Settlers – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By Frederick Webb Hodge in 1906

Mandan Man making an offer of the buffalo skull

A Siouan tribe of the northwest, the Mandan name is believed to be a corruption of the Dakota Mawatani. Before white settlers discovered the Indians, they called themselves simply “Numakiki,” meaning “people” or “people on the bank.” Their relations, so far as known historically and traditionally, have been most intimate with the Hidatsa; yet, judged by the linguistic test, their relationship may be nearer the Winnebago.

The Mandan traditions regarding their early history are scant and almost entirely mythological. All that can be gathered from them is the indication that they lived in a more easterly locality near a lake. This tradition, often repeated by subsequent authors, is given by Lewis and Clark as follows:

“The whole nation resided in one large village underground near a subterraneous lake; a grapevine extended its roots down to their habitation and gave them a view of the light; some of the most adventurous climbed up the vine and were delighted with the sight of the earth, which they found covered with buffalo and rich with every kind of fruits; returning with the grapes they had gathered, their countrymen were so pleased with the taste of there that the whole nation resolved to leave their dull residence for the charms of the upper region; men, women, and children ascended by means of the vine; but when about half the nation had reached the surface of the earth, a corpulent woman who was clambering up the vine broke it with her weight and closed upon herself and the rest of the nation the light of the sun. Those who were left on earth made a village below, where we saw the nine villages, and where the Mandan dies, they expect to return to the original seats of their forefathers, the good reaching the ancient village by means of the lake, which the burden of the sins of the wicked will not enable them to cross.”

Mandan Village by Karl Bodmer.

The Mandan affirm that they descended originally from the more eastern nations, near the sea coast. Due to their linguistic relation to the Winnebago and the fact that their movements in their historic era have been westward up the Missouri River, they correspond with their tradition of a more easterly origin. They would seemingly locate them in the vicinity of the upper lakes. It is possible that the tradition that has long prevailed in the region of northwest Wisconsin regarding the so-called “ground-house Indians” who once lived in that section and dwelt in circular earth lodges, partly underground, applies to the people of this tribe. However, other tribes of this general region formerly lived in houses of this character. Assuming that the Mandan formerly resided in the vicinity of the upper Mississippi, it is probable that they moved down this stream for some distance before passing to the Missouri River.

When first encountered by the whites, their reliance to some extent on agriculture as a means of subsistence would seem to justify the conclusion that they were at some point in the past in a section where agriculture was practiced. It is possible that they learned agriculture from the Hidatsa, but the reverse has more often been maintained.

Some theorize that they formerly lived in Ohio and built mounds before migrating to the northwest. The traditions regarding their immigration commence with their arrival at the Missouri River, which first reached the mouth of the White River in South Dakota.

Mandan Hide with symbols. Knife River Indian Village, North Dakota, by Kathy Alexander.

From this point, they moved up the Missouri River to the Moreau River, where they came in contact with the Cheyenne and where they also formed bands. They then continued up the Missouri River to the Heart River in North Dakota, where they were residing at the time of the first known visit of the whites. However, trappers and traders probably visited them earlier.

The first recorded visit to the Mandan was that of Sieur de la Verendrye in 1738. In about 1750, the Mandan were settled near the mouth of Heart River in nine villages, two on the east and seven on the west side. Lewis and Clark found remains of these villages in 1804. Having suffered severely from smallpox and the attacks of the Assiniboine and Dakota, the inhabitants of the two eastern villages consolidated and moved up the Missouri River to a point opposite the Mandan. The same causes soon reduced the other villages to five, whose inhabitants subsequently joined those in the Mandan entry, forming two villages, which in 1776 were likewise merged. Thus, the whole tribe was reduced to two villages, Metutanke and Ruptari, situated about four miles below the mouth of Knife River, on opposite sides of the Missouri River. These two villages were almost destroyed by smallpox in 1837, with only about 31 souls out of 1,600, according to one account, being left. However, other and probably more reliable counts make the number of survivors from 125 to 145. After that time, they occupied a single village. In 1845, when the Hidatsa were removed from the Knife River, some of the Mandan went with them, and others flowed at intervals. Others moved up to the village at Berthold as late as 1858.

Dance of the Mandan Indians by Karl Bodmer.

By a treaty made on July 30, 1825, the Mandan entered peaceable relations with the United States. They participated in the Laramie, Wyoming treaty of September 17, 1851, by which the northwest boundaries were defined. They also participated in the un-ratified treaty of Fort Berthold, Dakota, on July 27, 1866. By an Executive Order on April 12, 1870, a large reservation was set apart for the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Indians in North Dakota and Montana, along the Missouri and Little Missouri Rivers, which included the Mandan village, then situated on the left bank of the Missouri River.

By an agreement made at Fort Berthold Agency in December 1866, the Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa ceded a portion of their reservation to the United States.

When white explorers first discovered them, the Mandan were described as vigorous, well-made, somewhat above medium stature, many of them being robust, broad-shouldered, and muscular. Their noses, not so long and arched as those of the Sioux, were sometimes aquiline or slightly curved, sometimes relatively straight, never broad, nor had they such high cheekbones as the Sioux. Some of the women were robust and rather tall, though usually, they were short and broad-shouldered. The men paid the greatest attention to their headdress. They sometimes wore a long, stiff ornament at the back of the head made of small sticks entwined with wire, fastened to the hair and aching down to the shoulders, which was covered with porcupine quills dyed various colors in neat patterns. At the upper end of this ornament, an eagle feather was fastened horizontally, the quill end was covered with red cloth, and the tip ornamented with its hunch of horsehair dyed yellow. These ornaments varied and were symbolic. Tattooing was practiced to a limited extent, mainly on the left breast and area, with black parallel stripes and a few other figures.

Mandan women gathering berries.

The Mandan villages were assemblages of circular clay-covered log huts placed close together without regard to order. The huts were slightly vaulted and were provided with a sort of portico. In the center of the roof was a square opening for the exit of the smoke, over which was a circular screen made of twigs. The interior was spacious, with four strong pillars near the middle and several crossbeams supporting the roof. The dwelling was covered outside with matting made of willows and twigs, over which was laid hay or grass and then an earth covering. The beds stood against the hut wall consisting of a large square case made of parchment or skins, with a square entrance, and large enough to hold several persons, who lay very conveniently and warm on skins and blankets.

The Mandan cultivated maize, beans, gourds, and sunflowers and manufactured earthenware, the clay being tempered with flint or granite reduced to powder by the action of fire. Polygamy was common among them. Their beliefs and ceremonies were generally similar to those of the Plains tribes. The Mandan were always friendly to the United States, and beginning in 1866, a number of the men served as scouts.

In Lewis and Clark’s time, the Mandan were estimated to number 1,250, and in 1837, 1,600, but smallpox reduced them to between 125 and 150. By the turn of the century, the Mandan were estimated at 250.

There were the following divisions, which seem to have corresponded with their villages before the Mandan consolidated:

Horatamumake (Kharatanunanke)

Matonumake (Matonumanke)

Seepooshka (Sipushkanumanke)

Tanatsuka (Tanetsukanumanke)

Kitanemake (Khitanumanke)

Estapa (Histapenumanke)

Meteahke

Today, the Mandan are part of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation in New Town, North Dakota.

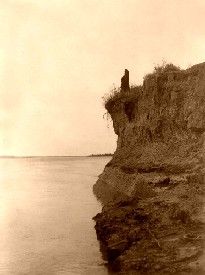

Mandan Indian atop the bluffs of the Missouri River.

Contact Information:

Mandan, Hidatsa & Arikara Nation

404 Frontage Road

New Town, North Dakota 58763

701-627-4781

Frederick Webb Hodge in 1906, Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

Also See:

The Arikara Tribe – Indians With Horns

The Hidatsa Tribe – North Dakota Pioneers