Stand Watie – Brigadier General of the Civil War – Legends of America (original) (raw)

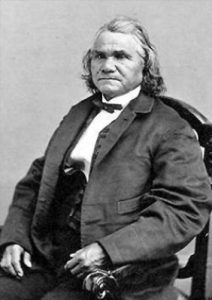

Stand Watie

Stand Watie, also known as Standhope Oowatie, Degataga, and Isaac S. Watie, was a leader of the Cherokee Nation and a brigadier general of the Confederate States Army during the Civil War.

Watie was born in Oothcaloga, Cherokee Nation (Calhoun, Georgia) on December 12, 1806, to David Uwatie, a Cherokee, and Susanna Reese. She was of Cherokee and European heritage and was first called Isaac Uwatie. Later, when he grew up, he preferred the English translation of his Cherokee name, Degataga, meaning “Stand Firm,” and the “U” was dropped from “Uwatie.”

Watie was educated at the Moravian Mission School in Spring Place, Cherokee Nation (now Georgia). By the time he grew up, his father had become a wealthy slave-owning planter. He would later write for the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper, which led him to dispute the Georgia Anti-Indian laws.

When gold was discovered on Cherokee lands in northern Georgia in 1828, thousands of white settlers encroached on Indian lands. Despite federal treaties that protected them from the actions of individual states, Georgia confiscated most of the Cherokee land, and the Georgia militia destroyed the Cherokee Phoenix in 1832.

The Federal Government soon stepped in, encouraging the Cherokee to move to Indian Territory. The Treaty of New Echota was signed in January 1836, establishing terms under which the entire Cherokee Nation was expected to move west. Although it was signed by a minority Cherokee political faction and not approved by the Cherokee National Council, it was ratified by the U.S. Senate. It became the legal basis for the forcible removal known as the Trail of Tears.

The Watie brothers stood in favor of removing the Cherokee to Oklahoma and were members of the group that signed the Treaty of New Echota. Following John Ross, the Anti-Removal National Party refused to ratify the treaty, putting him at odds with the Waties. Along with many other Cherokee, the family soon emigrated to the West, where Stand Watie, a slaveholder, started a thriving plantation on Spavinaw Creek in Indian Territory.

Those Cherokee following Chief John Ross remained on their tribal lands for two years until the U.S. government forcibly removed them in 1838 on the “Trail of Tears,” during which thousands died.

The following year, many of the members who had signed the treaty were targeted for execution, and in June 1839, Stand’s brother, Elias Boudinot, was murdered outside his home. His cousin and uncle, John and Major Ridge, fell to Cherokee assassins on the same day.

In 1842 Watie encountered James Foreman, one of his uncle’s assassins, and shot him dead. Even though Foreman was unarmed, he was tried for murder in Arkansas and acquitted as acting in self-defense. Ross partisans also murdered Stand Watie’s brother Thomas Watie in 1845. At least 34 politically related murders were committed among the Cherokee in 1845 and 1846.

From 1845, Stand Watie served on the Cherokee Council, part of that time as speaker.

When the Civil War broke out, most of the Cherokee Nation voted to support the Confederacy, and Watie organized a cavalry regiment. In October 1861, he was commissioned as a colonel in the First Cherokee Mounted Rifles. In December 1861, he was engaged in a battle with some hostile Indians in the Battle of Chusto-Talasah in present-day Tulsa County, Oklahoma.

Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas

Later, he would participate in the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in March 1862, after which General Albert Pike, in his report of this battle, said: “My whole command consisted of about 1,000 men, all Indians except one squadron. The enemy opened fire into the woods where we were, the fence in front of us was thrown down, and the Indians charged fully in front through the woods and into the open grounds with loud yells, took the battery, fired upon, and pursued the enemy retreating through the fenced field on our right, and held the battery, which I afterward had drawn by the Cherokee into the woods.”

Though the Battle of Pea Ridge was a Union victory, Watie’s command of his troops was well noted. There was considerable fear by the Union that Indian Territory would be entirely lost to the Confederacy.

The same year, though he served in the Confederate Army, Watie was elected principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. Though former Chief John Ross had fled to Washington D.C., his supporters, who by this time were in the minority, refused to recognize Watie’s election, and open warfare broke out between the “Union Cherokee” and the “Southern Cherokee.”

Confederate General William Steele, in his report of the operations in the Indian Territory, in 1863, said of Colonel Watie that he found him to be a gallant and daring officer. On April 1, 1863, Watie was authorized to raise a large brigade.

In May 1864, Colonel Watie was commissioned a brigadier-general, the only Native American to achieve that rank in the Civil War. In June, he captured the federal steamboat, J.R. Williams, with 150 barrels of flour and 16,000 pounds of bacon, which Watie would later say was actually a disadvantage to the command because a significant portion of the Creek and Seminole soldiers immediately broke off to carry their booty home. In September 1864, he attacked and captured a Federal train of 250 wagons on Cabin Creek and repulsed an attempt to retake it.

At the end of the year, 1864 General Watie’s cavalry brigade consisted of the First Cherokee regiment, a Cherokee battalion, First and Second Creek regiments, a squadron of Creeks, First Osage Battalion, and First Seminole battalion. To the end of the War, General Watie stood by his colors, becoming the last Confederate general in the field to stand down. When the leaders of the Confederate Indians learned that the government in Richmond, Virginia had fallen and the Eastern armies had been surrendered, most began making plans for surrender.

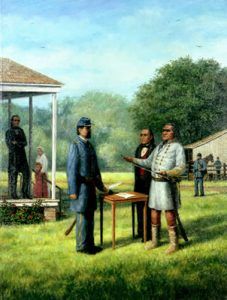

Surrender of Stand Watie at Doaksville, Oklahoma, painting by Dennis Parker, courtesy of the Oklahoma Senate.

The chiefs convened the Grand Council on June 15, 1865, and passed resolutions calling for Indian commanders to lay down their arms. However, Stand Watie refused until June 23, 1865, a full 75 days after Lee’s surrender in the East. Finally accepting the futility of continued resistance, he surrendered his battalion of Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, and Osage Indians to Lieutenant Colonel Asa C. Matthews at Doaksville.

After the Civil War ended, the “Union Cherokee” and the “Southern Cherokee” sent delegations to Washington D.C., where Watie pushed for recognition of a separate “Southern Cherokee Nation.”

Watie was refused; however, and the government negotiated a treaty with the “Union Cherokee” in 1866, declaring John Ross as the rightful Principal Chief. It seemed that open hostilities would break out again in the Cherokee Nation, but when John Ross died in August 1866, hostilities calmed down. In the election in 1867, full-blood Cherokee, Lewis Downing, was elected Principal Chief and was able to bring about peaceful reunification, though tensions lingered under the surface into the 20th century.

In the meantime, Watie had returned from the Civil War to find his home burned to the ground by Federal soldiers. In financial ruin, he spent his final years farming and trying to restore his once-beautiful Grand River bottomland.

All three of Watie’s sons preceded him in death. In his last years, he watched as colossal tracts of land legally deeded to the Cherokee were taken from them as punishment for supporting the Confederacy and given to other tribes. Many believe that Stand Watie died of a broken heart. In one of his last letters to his daughter, he would say, “You can’t imagine how lonely I am up here at our old place without any of my dear children being with me.” On September 9, 1871, he died and was buried in the Polson Cemetery in Delaware County, Oklahoma.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2021.

Also See:

John Ross – Chief of the Cherokee Nation