Ghost Towns in Indian Country of New Mexico – Legends of America (original) (raw)

You must keep your eyes wide to spot the crumbling ruins along Route 66.

From the Laguna Pueblo, Route 66 continues west through Indian Lands, passing through several ghost towns before reaching Grants, New Mexico. Along this stretch, you will see numerous ruins and foundations dotting the landscape. Made of native stone, these rustic old buildings easily blend into the surrounding countryside, so you must keep your eyes wide open and your camera ready.

Budville

Just a few miles west of Paraje, Route 66 travelers will reach Budville, the once-active trading center.

Budville Trading Company.

Named for H.N. “Bud” Rice, it started when Bud and his wife Flossie opened an automobile service in 1928. Soon afterward, they opened the Budville Trading Company. Over the years, it has been a gas station, a few cabins, and the only tow company between the Rio Puerco River and Grants for several years. They also sold bus tickets and operated a post office. Bud served as the Justice of Peace, a position in which he was known to have issued steep fines, especially to anyone outside the area.

Having operated the business for 39 years, a desperado held up the store in November 1967. Four people were in the building — Bud, Flossie, an 82-year-old retired school teacher named Blanche Brown, who worked part-time, and a housekeeper named Nettie Buckley. Within moments, shots were fired, and the gunman fled, leaving behind a scene that would earn the trading post the moniker of “Bloodville.” Fifty-four-year-old Bud Rice and the elderly shopkeeper Blanch Brown were dead. Flossie and the housekeeper survived. Though arrests were made, no one was ever convicted of the crime.

Closed Cafe in Budville, New Mexico.

Afterward, Flossie continued to run the family businesses and remarried a man named Max Atkinson. Six years after losing Bud, her second husband was killed in a fight in 1973, just feet from where Bud had been killed. Once again, Flossie persevered and continued to run the business until 1979, when its doors closed for good after 66 years in business. Somewhere along the line, she married for the third time and passed away from natural causes in 1994. The buildings were eventually sold, and there was some talk of it being reopened, but it never occurred.

Across the street is the closed Dixie Bar, established in 1936, and down the road, just a bit, is the old King’s Café and Bar with its vintage signage. Today, the cafe’s name has been changed to the Midway, where travelers can still get a hot meal and a cold beverage on this lonely stretch of the highway.

Cubero

In Budville, between the Budville Trading Company and the old Dixie Bar, the pre-1937 alignment (Old Route 66) splits off Highway 124 and heads northeast for about 1.5 miles to the centuries-old village of Cubero. Initially, this was the site of a pre-Spanish Colonial-era pueblo. The earliest known documentation of the village dates to 1776. In its early days, the settlement served as a garrison town for the Spanish.

In 1833, the government of the Republic of Mexico made a land grant to a group of people to form a colony at the site. In 1866, a mission was established, and Our Lady of Light Catholic Church was built. The building, constructed of 40-inch thick adobe walls, also served as a refuge against Apache and Navajo raids. For many years, an abandoned cannon remained on the church grounds. Unfortunately, flash floods weakened the church walls, and the construction of a new church began in 1972 and was dedicated in 1975.

During the early 1920s, the area was discovered by tourists traveling through the Southwest in automobiles along the National Old Trails Highway. Old trading posts and new businesses sprang up to capitalize on this opportunity. Wallace and Mary Gunn operated one of these trading posts. They did good business by providing the locals with groceries, dry goods, and coal oil in exchange for livestock, pottery, and Indian art. The crafts of locals were then sold to the attentive tourists. But, the tourist traffic wouldn’t last for the village of Cubero. In 1937, Route 66 was realigned, bypassing Cubero and making a path directly from Budville to San Fidel.

Villa De Cubero Trading Post.

Route 66 travelers can return to the newer alignment by backtracking on old Route 66 or by heading west onto Cubero Loop, which will hook up with Highway 124 (the post-1937 alignment of Route 66).

Shortly after the realignment of Route 66, Wallace and Mary Gunn relocated their business to the new alignment. Called the Villa De Cubero Trading Post, the complex grew to include a service station, cafe, and a small tourist court. The villa became popular with celebrities such as Dezi and Lucy Arnez, Vivian Vance, and the Von Trapp family. Reportedly, Ernest Hemmingway resided in the small tourist court for two weeks while working on The Old Man and the Sea. Mary Gunn ran the cafe across the street from the trading post from 1941 to 1972.

Though the cafe and tourist courts are closed, the trading post still caters to Route 66 travelers today, operating a convenience store and gas station.

Route 66 continues from the Villa Cubero through stretches of the desert surrounded by beautiful multi-colored formations. It then travels the short three miles to yet another ghostly town, San Fidel. Mount Taylor, one of the highest peaks in the area, is visible along this section, and the fading remains of several long-closed tourist facilities are visible.

San Fidel

St. Joseph Church, San Fidel, New Mexico.

San Fidel, a small Hispanic community today, was established in 1868 when Baltazar Jaramillo and his family settled here. In its early years, it had no church, but the community residents could worship when priests visited from Seboyeta and San Rafael. A church was built for the people of the village in 1892. It was first called Ballejos and gained a post office in 1910. However, its name was changed to San Fidel in 1919, honoring the saint, a suggestion made by an area priest.

St. Joseph Church was built in 1920, and the following year, San Fidel became a parish because of its central location in the Acoma and Laguna Pueblos and the villages of Cubero, Seboyeta, Moquino, Bibo, San Mateo, San Rafael, and Grants; as well as its proximity to the railroad. The rectory was built in the early 1920s and housed the priests who served the missions for many years. In 1924, a school was built and first served as a public school. Later, it became St. Joseph Mission School and still serves about 50 pre-K to 8th-grade children from the Laguna and Acoma Pueblos and the Spanish villages of Cubero and Seboyeta.

As the years passed, other parishes were established, and only Cubero remained as a mission of San Fidel. That, too, changed when Cubero was entrusted to the care of a pastoral administrator. In 1981, the rectory was converted into a convent for the Sisters who staff the school. Today, St. Joseph’s Church is only used on special occasions.

San Fidel Mission Church.

Unlike the other small towns along this stretch, San Fidel is not a ghost town, as it boasts about 135 people and still has a post office. In the old days, this fading town had several cafes and automobile services. Today, it still supports a mechanics garage, a church, a school, and an art gallery/gift shop. Back in the heydays of Route 66, it was not at all uncommon to see Indians sitting along the roadway selling pottery in addition to having numerous open businesses.

One humble building in the community that few people would notice today was once a popular stop for travelers and is on the National Register of Historic Places. The Acoma Curio Shop was built by Abdoo Fidel, an immigrant from Lebanon, in 1916 of adobe bricks. But unlike so many other adobe buildings in the Southwest, it also features a false front more common to mining boomtowns, making it a rare blend of two distinct architectural styles. While such blending is typical in roadside vernacular architecture, this combination is unusual, especially in New Mexico, and adds to the appeal of one of the few rural curio shops remaining along Route 66 in the state. A metal-roofed porch faces the highway, supported by four simple wooden posts. The north and west sides are neatly coated in white stucco, while the eastern wall mostly has exposed adobes, showcasing the original construction.

San Fidel Gallery/Gift Shop.

Fidel originally opened a small mercantile business in the building and later moved to a larger building on the west side of town that housed his store and his family. The highway through San Fidel became part of Route 66 when commissioned in 1926, and traffic increased significantly in the coming years. Perhaps sensing an opportunity to capture tourist dollars, Fidel began wholesaling local Native American crafts and, in 1937, moved this operation into the original mercantile building, where he opened a retail business named the Acoma Curio Shop. Unlike most curio shops in the Southwest, which featured an assortment of crafts from different pueblos or cultures that were sometimes of dubious authenticity, Fidel dealt exclusively with local Acoma artists.

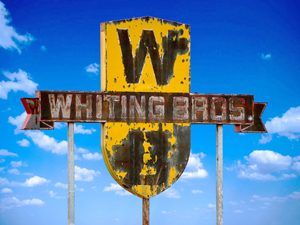

Old Whiting Brothers Sign in San Fidel, New Mexico.

World War II and its accompanying gasoline rationing curtailed travel along the highway, and the Curio Shop closed soon after America entered into the conflict. Fidel refocused his attention on his larger mercantile store, leasing the Curio Shop to the Standard Oil Company, which operated as a service station for several years. Afterward, the building was called home to multiple tenants. While the building has undergone minor alterations, it has maintained a high degree of historical integrity and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. Like so many other old business buildings in San Fidel today, it sits silent and empty.

Continue west on NM-124, about 2.5 miles, to view a once-busy Whiting Brothers complex, which included a motel, gas station, and grocery store. Probably built in the 1940s, it might have been the place mentioned by Jack Rittenhouse in his A Guide Book to Highway 66, written in 1946: “Chief’s Rancho Cafe here, with gas, grocery, curios, and cafe” two miles west of San Fidel.

Nothing remains of the motel and grocery store except pavement and debris. The old gas station, abandoned long ago due to fire damage, remains. Where the motel once stood is nothing but a However, its majestic sign continues to stand.

McCartys

Santa Maria de Acoma Mission. Photo courtesy Mark Goebel.

Just a few more miles beyond the old Whiting Brothers Station brings the Route 66 traveler to the edge of McCartys as the Mother Road passes to the north and west of the settlement. However, when the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad came through in the 1880s, McCarty was named for a railroad contractor who had his camp here. A post office was established in 1887 and continued to operate until 1911. There are many remnants of the historical past in this quiet little town. In the early days of Route 66, women and children dressed in traditional Pueblo costumes could be seen in abundance seated underbrush shelters selling baskets and Acoma pottery.

What can be seen from the road today is primarily a collection of small homes and ruins and the beautiful Santa Maria Mission just west of the village. The beautiful Santa Maria de Acoma Mission, sitting up on the hillside, was dedicated on November 28, 1933, by Archbishop Gerken of Santa Fe. A parish hall was constructed there in 1969. The simple stone building was constructed in the Spanish Colonial style, in one half-size replica of the ancient church of old Acoma. Its interior provides views of several notable wood carvings.

McCartys is the gateway to the Acoma Pueblo, some 13 miles to the southeast on BIA-38. Be aware that the pueblo allows entry only between March and October by guided tours, about 1 1/2 hours long. There is a fee for the tour, and cameras are not allowed without purchasing an additional license per camera.

From here, old Route 66 can be traveled along a historic route to Grants, some 14 miles ahead.

Initially aligned along the National Old Trails Highway, this old section of historic pavement has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places, and you will see why when you travel this vintage ribbon of the road. All along the journey, you will see black masses of hardened lava on both sides of the road. These great lava flows, ranging from 50 to 200 feet wide, curve about the flat valley all along the route. This lava flow, called “The Malpais,” meaning “Evil Country,” is one of the most recent in U.S. history, occurring between 1,000 and 2,000 years ago. Navaho legend says that this lava is the blood of the great giant slain by the Twin War Gods in the Zuñi Mountains. Here in this area lies the remains of deserted pueblos, caves of perpetual ice, hideouts of Old West outlaws, and numerous tales of buried treasure.

Road-building was an engineering challenge when it was built crossing the basaltic flows of the Malpais badlands. New Deal programs during the Great Depression improved the road and paved it between 1935 and 1936. A steel pony truss bridge was built in 1936 across the San Jose River

In 1956, I-40 replaced the road, which became its south frontage road between McCartys and the junction of I-40 and NM-117.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2024.

Also See:

New Mexico – Land of Enchantment

Sources:

Dusty Track

Hinkley, Jim; The Illustrated Route 66 Historical Atlas, Voyageur Press, 2014

Hinkley, Jim; Route 66 Encyclopedia, Voyageur Press, 2012

Julya, Robert; Place Names of New Mexico; UNM Press, 1996

National Park Service

Voice of the Southwest