Fort Wingate, New Mexico – Reining in the Navajo – Legends of America (original) (raw)

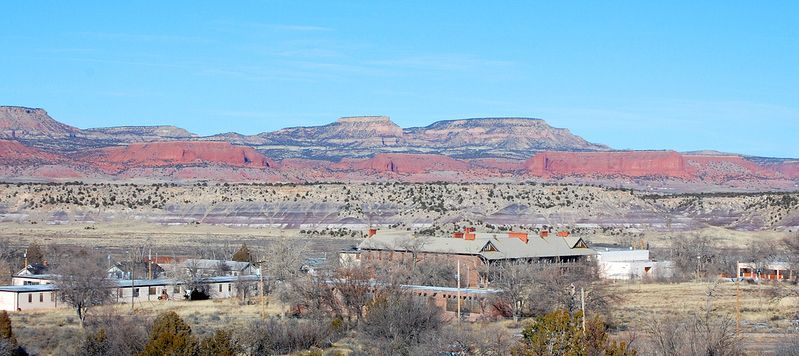

Remaining buildings of Fort Wingate, NM. Photo by Kathy Alexander, 2015

Located in McKinley County, sitting among the red rocks along Interstate 40, this is the second site of Fort Wingate. The first fort (1862-68) was located at El Gallo, 65 miles to the southeast. It was founded by Colonel Kit Carson, along with Fort Canby, Arizona (1863-64), for his 1863-64 campaign against the Navajo. General James Carleton, commander of the Department of New Mexico (a regional designation predating statehood), believed that confining the Indians to reservations was the best solution to the conflict between encroaching white settlers and the Native Americans. Joined by Ute allies, Carleton led forces against the Navajo, destroying sheep and homes and finally removing thousands of them, to the Bosque Redondo Reservation in a 400-mile trek called The Long Walk.

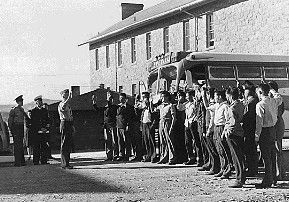

Fort Wingate, New Mexico, 1873

After the Navajo were confined to the Bosque Redondo Reservation, troops from Fort Wingate patrolled for stragglers and raiders. In a commanding position on the Albuquerque-Fort Defiance Road, it also protected miners en route to the Arizona goldfields and, in 1864, took part in the Apache.

The Bosque Redondo Reservation, situated near Fort Sumner, New Mexico, operated for four years. Poor growing conditions and lack of water on the reservation resulted in malnutrition and disease among the Navajo. In 1868, the Navajo and U.S. government representatives signed a treaty allowing the Navajo to return to their homes. The treaty also provided replacement livestock in return for the Navajo’s pledge to confine themselves to a finite area and cease raiding activities.

When the Navajo returned to their homeland, the Army relocated Fort Wingate to its second site. It was located nearer the new Navajo Reservation, administered by the Fort Defiance Indian Agency. The site had previously been occupied by Fort Fauntleroy, or Lyon (1860-61), whose mission had also been Navajo control but had been evacuated before the Confederate invasion of New Mexico from Texas.

Besides policing the reservation, the garrison of the new fort participated in the Apache campaigns to the south and became an incarceration facility for captured Apache. Another one of its roles was to protect the construction activities of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, which played a key role in fostering western settlement.

Many soldiers stationed at Fort Wingate found their conditions grim. Lieutenant John Pershing wrote to a correspondent.

“This post is a… and no question – tumbled down, old quarters, though Stots is repairing it as fast as he can. The winters are severe… it is always bleak, and the surrounding country is barren absolutely.”

An 1896 fire destroyed many of the fort’s buildings, which the military replaced with buildings of local red sandstone shortly after 1900.

The Army withdrew in 1910, and the fort was decommissioned in 1912. The fort briefly served again in 1914 and 1915 when an internment camp in a fenced enclosure just north of the post housed refugees from the Mexican Revolution. In 1918, the United States Ordnance Department reactivated the fort as the Wingate Ordnance Depot. In 1925 the depot was moved closer to the railroad, and a Navajo school took over the buildings.

Navajo Code Talkers at Fort Wingate, New Mexico

Route 66 became an important artery for military logistics during World War II, making military sites busy and supporting economic growth in nearby communities along the way. War heightened the demand for munitions storage facilities. Fort Wingate became a significant storage center with its earthen, igloo-like storage buildings visible from Route 66.

However, Fort Wingate’s most famous contributions to World War II were the Navajo code talkers who trained here. The code talkers baffled Japanese forces in the Pacific using a code based on the Navajo language.

Until the late 1950’s Fort Wingate was one of the best-preserved frontier military posts in the Southwest. From 1958-60, the Bureau of Indian Affairs razed the officer’s quarters along the south side of the parade grounds and one of the barracks to allow for the construction of more modern school facilities. More recently, in January 1976, the kitchen-dining hall was razed.

From 1918 until its closure in 1993, the 22,000-acre installation stored and demolished ammunition. In negotiations with the tribes, the Army Base Realignment and Closure Program transferred half of the 22,000 acres to be used jointly by the tribes, retaining the other half for missile testing and launching.

Remaining at Fort Wingate today are several historic features. The fort retains parade grounds from its military period, an 1883 adobe clubhouse, one barracks, and a row of 1900 officers’ quarters. The cemetery remains, though most military burials, were removed to the Santa Fe National Cemetery in 1915.

Fort Wingate contains sites rich in cultural heritage and historical significance. Over 200 Navajo ruins were discovered on the property and several modern earth-covered dwellings called “hogans.” The property served for centuries as a hunting and gathering area for the Zunis. Over 600 archeological sites were recorded by surveyors, including an additional 200 ruins traceable to the Anasazi, ancestors of the Zuni.

Fort Wingate Historical Marker, 2015

Efforts to clean up the property have focused on removing exploded and unexploded ordnance. Given the cultural and historical significance of Fort Wingate, the first step of the restoration process involved identifying the numerous cultural and historic resources affected by the cleanup and disposal of the property. Environmental cleanup and land transfer to the surrounding community continue today, and the remaining fort buildings stand behind posted wire fencing.

The National Park Service listed the Fort Wingate Historic District in the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

Fort Wingate is approximately 12 miles southeast of Gallup, New Mexico.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.