Goldfield, Nevada – Queen of the Mining Camps – Legends of America (original) (raw)

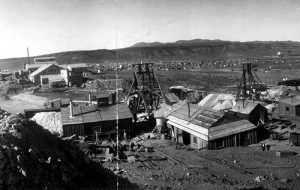

Goldfield, Nevada, around 1906 or 1907. Touch of Color by LOA.

In December 1902, gold was discovered in the hills south of Tonopah, Nevada, by two grub stake prospectors named Harry Stimler and Billy March. In no time, tents began to dot the barren hills in the mining district dubbed “Grandpa,” later named Goldfield. Just a year later, only 36 people lived in the new town, but that would quickly change as gold began to be mined in the area in larger and larger quantities.

Early prospectors built dugout houses in Goldfield, Nevada.

In the summer of 1903, miners who had spent the previous winter in Goldfield living in quickly constructed shanties or tents devised a better solution.

Soon, they began to dig new homes along the banks of Coyote Wash. Brownstones from the canyons of Malpai Mesa were hauled in to close the fronts of these hurriedly dug caves, making them more suitable against the harsh winter winds and the heat of the summer desert. Some parts of these old brownstone homes were still evident as late as the 1940s, but today it is almost impossible to determine where these structures once stood.

By 1904, the town supported three saloons, a grocery store, and two feedlots, along with its area mining operations. In the spring of that same year, Virgil and Wyatt Earp arrived in Goldfield, chasing the prospect of easy riches. Though Virgil’s arm was atrophied from the bullet he had taken in Tombstone, Arizona, in 1881, he was soon sworn in as a deputy sheriff in Goldfield. In February 1905, Tex Rickard opened the Northern Saloon, Goldfield’s most celebrated saloon and gambling house. Wyatt, who had met and become friends with Tex in Nome, Alaska, was hired as a pit boss.

Virgil Earp

On July 8, 1905, Goldfield suffered its first significant fire when a stove exploded in the Bon Ton Millinery shop. The flames soon spread to adjoining structures. Without enough water to fight the quickly spreading flames, beer was used as an extinguisher. The July 9, 1905 issue of the Tonopah Daily Sun reported:

“The buildings of the Enterprise Mercantile Company were saved by the free and unlimited use of beer. Barrel after barrel was used and had a most desirous effect. Had it not been for the liquid the entire stock of goods of the company would have been ruined.”

Goldfield was finally saved when the wind shifted, but not before two blocks of businesses and homes had burned to the ground.

1905 also saw the arrival of the Tonopah & Goldfield Railroad, much to the relief of its many residents. It was also this year that the Santa Fe Saloon was built. One of Goldfield’s oldest continuously-operating businesses, the saloon continues to offer four motel rooms as well as being a popular oasis in the desert. Complete with its false-front, western wood sidewalks, and rough floor planking, inside sports an original Brunswick Bar, dominating the Santa Fe’s back wall.

In October Virgil Earp contracted pneumonia, so sick that his doctor cut him off his favorite cigars. On October 19, 1905, he seemed to rally, asking his wife Allie for a cigar. Believing he was getting better, she gave him one. He then requested that she sit with him, holding his hand. Before he finished the cigar, he had died. Virgil’s remains were taken to Portland, Oregon, where he lies at the Riverview Cemetery. Wyatt left Nevada shortly after Virgil’s death.

Santa Fe Club Saloon in Goldfield established 1905.

In 1906, the town reached its peak with a population of over 30,000, when as much as $10,000 a day in ore was being taken from the mines.

The town was called the “Queen of the Mining Camps” for its luxury and availability of saloons and other forms of entertainment, including its many sporting houses. At this time, building lots often sold for as much as $45,000. In addition to its numerous saloons, the town boasted three newspapers, five banks, and a mining stock exchange.

On Labor Day 1906, Goldfield was chosen as the site of the Gans-Nelson Lightweight Championship of the World. Tex Rickard’s Northern Saloon staged the prize fight, building an 8,000 seat arena, but more than twice that many people turned out to watch the fight. The fans got their money’s worth as the bout went 42 rounds, a record that still stands in the Guinness Book of World Records. The winner, Joe Gans, walked away with a $30,000 purse.

The Mohawk Mine was one of the many mines in Goldfield in 1906.

Soon after mining on an extensive scale began, the miners organized themselves as a local branch of the Western Federation of Miners. The Goldfield Consolidated Mines Company, primarily owned by George Wingfield, held a virtual monopoly in Goldfield, which led to an adversarial relationship between mine owners and the unions. There were several strikes in December 1906 and January 1907 for higher wages, with more strikes continuing throughout the year for various reasons. Though there had been no serious disturbance in Goldfield, George Wingfield appealed to President Roosevelt in December 1907 to send Federal troops, on the grounds that the situation was ominous. With no state militia to maintain order, the president ordered a California division in San Francisco to march upon Goldfield with 300 federal troops.

The troops arrived in Goldfield on December 6, 1907, and the mine-owners immediately reduced wages and announced that no members of the Western Federation of Miners would thereafter be employed in the mines. The troops remained in Goldfield until March 1908, with the contest of wills having been won by the mine owners.

From 1903 to 1910, Goldfield was the largest city in Nevada, and in 1907, the county seat was moved to Goldfield from Hawthorne. Soon the city fathers set about to construct a new courthouse, a two-story fortress-like building that continues to stand today. The large stone structure opened in May 1908 with a jail added onto the rear of the building.

Vintage photo of the Goldfield Hotel

In 1908, the Goldfield Hotel, designed by Architect George E. Holesworth, and owned by George Wingfield, was opened amidst an array of fanfare. Built over a mine shaft that had gone dry, the structure cost over $300,000. The four-story building of stone and brick contained 154 rooms with every modern convenience including telephones, electric lights, and steam heat. The lobby was paneled with mahogany and furnished in black leather beneath gold-leaf ceilings and crystal chandeliers. The hotel imported chefs from Europe and boasted one of the first Otis elevators west of the Mississippi River. Considered to be the most luxurious hotel between Chicago and San Francisco, it appealed to society’s upper crust, making owner George Wingfield an even wealthier man.

However, the prosperity was not to last. By 1910, the town’s population had dwindled to about 5,000 and by 1912; gold production had dropped to from its former high of 11 million dollars per year to 5 million dollars.

This old miner’s cabin in Goldfield survived the flood by Kathy Alexander.

A year later, on September 13, 1913, Goldfield suffered a devastating blow when heavy rains in the hills to the west caused a rolling wall of water to pour into the city, sweeping away hundreds of buildings and all their contents, including many of the sporting girl’s cabins, prospector’s homes, and the Moose Hall.

One resident reported two sacks of gold were washed away from his cabin. Another man, not in Goldfield at the time, later reported that he had buried several stolen sacks of high-grade ore at his cabin. When he returned for the money, not only could he not find the gold, but the cabin itself was long gone, washed away by the waters of the gulch.

Another report stated that two safes containing hundreds of gold coins were lost in a gully west of town. For decades following the flood, prospectors crossing west of Goldfield would find a “previously dug” nugget or a gold coin, but the reported lost caches have never been found. The area west of the city continues to be a treasure hunter’s paradise today.

By 1918, the mines produced only 1 ½ million dollars in ore, with half that amount in the next year. By 1920, the town was called home to only about 1,500 residents and for the next three years, only a cumulative $150,000 in ore was produced by the area mines.

But Goldfield’s misfortunes were not yet complete. On July 6, 1923, a moonshine still exploded across the street from the Goldfield Hotel early in the morning hours. With raging winds, the fire blazed for 13 hours before it was brought under control. Spreading down Main Street, the inferno took out many of the town’s businesses, destroying 27 blocks of homes and buildings in its path. The town never recovered.

Goldfield Hotel by Kathy Alexander.

At about this same time the Goldfield Hotel began a gradual decline and by the 1930s, when the town supported fewer than 1,000 souls, it had become little more than a flophouse for cowboys and undiscriminating travelers.

During World War II, it was used to quarter soldiers and afterward closed its doors forever. Over the years, the hotel has changed hands numerous times, most recently in 2003. Though there are plans to renovate and reopen the old hotel, as of this writing, it continues to stand lonely and deserted.

In just a few more years the last of five railroads that had once hauled millions of dollars in ore from Goldfield — the Tonopah & Goldfield, discontinued operations in 1947.

From 1903 to 1940, Goldfield’s mines produced more than $86 million dollars. As late as 1997, a few of the Goldfield mines were still producing.

Today, though Goldfield is called home to less than 500 residents and is all but a ghost town, it still retains the title as the Esmeralda County Seat. The courthouse has been in continuous use by the county since the building opened in 1908. Built of native sandstone resembling a castle, it was one of the most elaborate in the state at the time it was built. Inside one of the courtrooms, you will find original Tiffany lamps. Behind the courthouse, the original jail also continues to stand, containing three levels of metal cells; two levels of which still house inmates in 18 cells.

More buildings in Goldfield offer glimpses of its more prosperous past. The Santa Fe Saloon built in 1905 continues to operate at the entrance to the mining fields. Across the highway from the Goldfield Hotel is the Mozart Saloon, which continues to serve breakfast, lunch, and drinks next to its antique bar.

Goldfield School

Across from the County Courthouse is Goldfield’s old High School. Though long closed, it displays a classic example of early 20th-century architecture. Across the street in another direction is the former Tex Rickard home, one-time owner of the famous Northern Saloon that masterminded the famous Nelson-Gans prize fight in 1906. The quaint Victorian home was built in 1905 and continues to stand at the corner of Crook and Franklin Streets. Tex Rickard went on to become a major boxing promoter and ultimately gained fame as the man who built the original Madison Square Garden in New York City.

The Goldfield Hotel continues to be the centerpiece of the town and when it opened in 1908 it was the most luxurious hotel in the state. Though it now stands dark and empty, it’s an impressive building symbolizing Goldfield’s former glory. The old hotel is also considered to be one of the most haunted buildings in the United States. For more on the Goldfield Hotel, its history and hauntings, click HERE.