Early Mining Discoveries in Nevada – Legends of America (original) (raw)

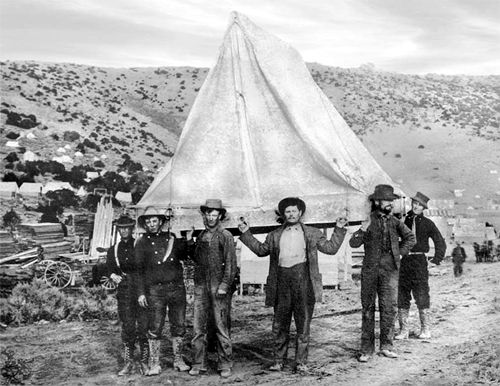

Eldorado County, CA Miners

By Sam P. Davis in 1913

The story of the first discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, was the beginning of a significant event in the history of the United States, which led to the mad rush of fortune hunters to the Pacific Coast and gave the world a romance of sudden wealth which has never been duplicated in the history of mining. For the next ten years, the record was one of tragedy and greed, of gilded adventure and extraordinary happenings, in which the soldiers of fortune from the uttermost parts of the earth plunged into the seething melting pot of fate and fought for spoils so vast and so easily acquired that it made the tale of Aladdin’s Lamp a jest and mockery.

The romance of California gold mining needed a sequel. The opening chapter was written when the Grosh brothers of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, first discovered silver in Nevada on the eastern slope of Mt. Davidson.

Now and then, a hand reaches down and brings up some fragment that calls to mind the incidents that cluster about that tremendous discovery that helps make a new State and contributes a page to the history of the world.

After the bloom had worn off the gold excitement in California, some men who had rushed to the Coast doubled along the trail and began hunting for the precious metal in Nevada.

Gold is not a modest metal. It makes its presence known whenever it can and is always seeking recognition. When, in its original location, it is always subject to dislodgment from the attrition of the elements, the convulsions of nature, and the thousand and one disturbances arising from the industry of man. When it is loosened from its original home, it becomes subject to the law of gravitation, and every movement is downward. Every storm that beats upon it helps to disintegrate its prison walls, and at every turn, the stones of the stream fall upon it and hammer it flatter. At the same time, the wear of the water takes away its sharp edges so that when a practiced prospector picks it up from the bottom of his pan scores of miles from the original ledge, the appearance of the little grain of gold gives him a tolerably good idea of the distance it has traveled.

Early in the 1850s, prospectors found gold in the Carson River, near present-day Dayton, and they followed the indications up the ravine, which carried away the wash of Mt. Davidson. They found the precious metal in paying quantities all along this gulch, which were washing out gold on the mountain’s eastern slope. Gold hunters from Placerville, California, had come to the river as early as 1854 and earned good wages with pick and pan in what is now known as Six-Mile Canyon.

The Grosh Brothers

In 1857, E. Allen Grosh and Hosea B. Grosh, sons of Reverend A. B. Grosh, a Unitarian clergyman of Philadelphia, were working on the Comstock. From the testimony of many miners who knew them, they were men of considerable scientific attainments, chemists, assayers, and metallurgists. In addition to all this, having quite an outfit of assaying implements, they also brought with them to a spot afterward occupied by the Trenck Mill, quite a formidable library of scientific works. Captain Gilpin and George Brown were also regarded as partners of the Grosh brothers.

They went to the Comstock region from Mud Springs, California, in 1857 and prospected for nearly a year. They took him along when they came across a young man named McLoud. He was a Canadian, about twenty years of age, and had crossed the plains with some Mormon emigrants.

The Grosh brothers occupied the cabin along with young McLoud, and Henry Tompkins Paige Comstock, after whom the ledge was named, was a frequent visitor to their little home.

Gold panning

By this time, considerable mining had been done about Mt. Davidson, but it was all for gold. The black sulphurets, rich in silver, were regarded as of no value and thrown away. The presence of these sulphurets was regarded everywhere with disfavor by the miners.

There is no authentic record of any assay made by the Grosh brothers. Still, they had the necessary work equipment and must have made the assay. In the fall of 1857, they told Comstock that they knew of rich silver mines in the vicinity and were going back to Philadelphia to secure capital to work them.

They once staked off several claims, but there was no mining district then. Naturally, they could not have recorded them. They asked Comstock to remain at their cabin during the winter with McLoud, who had been engaged to cut wood and take care of the cabin until they returned.

While preparations were being made for the departure of the Grosh brothers to Philadelphia, Hosea, while prospecting, ran a pick in his foot, which eventually resulted in lockjaw, from which he died on September 2, 1957. He was buried near their camp, and a few large rocks marked his grave. Years later, his father would send a slab from Philadelphia to mark the grave.

With his brother, Hosea, dead, Allen didn’t go to Philadelphia but would soon travel along with McLoud to Last Chance, California. About November 1, the pair started across the mountains for Mud Springs through Georgetown. They crossed into California by way of Lake Tahoe, then known as Lake Bigler. While crossing the Sierra Nevada Mountains, they were caught in a succession of snowstorms, suffering terribly and nearly freezing to death. However, they finally reached Last Chance in Placer County. By this time, both men’s feet were frozen. McLoud had his feet amputated, but Grosh refused. He died in December 1857 and was buried in the area. Neither one of the Grosh brothers nor their families ever realized a dollar from their discovery, which added to the world’s wealth of over seven hundred million dollars and saved the American Union in the Civil War.

McLoud, however, survived to tell the tale of the first silver assay made on the Comstock. What it amounted to, the Grosh brothers kept to themselves. But McLoud told the storekeeper in Last Chance that he saw the Groshes “pour some of the silver ore in a glass after pounding it in a pot and wetting it” and that after that, “they got very much excited.” The assay thus described by McLoud was unquestionably the first assay ever made of the silver deposits of the Comstock. McLoud later moved to Montreal, Canada, where he practiced medicine.

What a subject this scene would have made for a painter’s brush — in the interior of a miner’s camp at night, the faces of two fortune-seekers lit by the ruddy glow of the cupel furnace as they eagerly held up the glass where the silver button had dissolved in the acid solution!

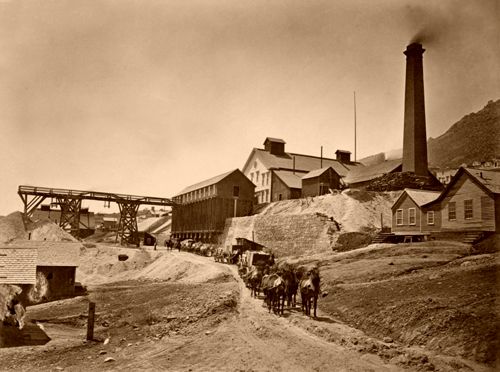

Hoisting Works Virginia City NV 1890.

On the result of that assay, the fortune of thousands hung. Out of that assay sprang the millionaires of the Coast, blocks of the finest buildings that now adorn San Francisco. These great enterprises have made Nevada and California famous, and along with it, a landslide of misery and bankruptcy that carried thousands to the foot of the hill to be covered with the debris of shame and oblivion. Out of the little glass came a giant more powerful and relentless than the awful shape that sprang from the pan in the Arabian story, and this giant continued to live to make and unmake the destinies of thousands.

A man named George Brown, who was out on the Humboldt River, was in some way a partner of the Grosh boys, but in what way has never been clearly stated. He was murdered at Gravelly Ford on the Humboldt River shortly before Hosea Grosh injured his foot. The Grosh boys mentioned him as “our partner.” They said he was coming to help them with $600. When they heard of his death, they were very despondent. They learned the news of Brown’s death from a Mrs. Louisa M. Ellis, whose name at that time was Mrs. Ellis. She later stated that she met the Grosh brothers in Nevada as early as 1854.

They told Mrs. Ellis in 1857 of their discoveries and pointed to Mt. Davidson, saying that the big silver ledge was at the foot of the mountain and that they had put her down for 300 feet to locate their claims. Mrs. Ellis became quite interested in the discoveries and proposed to sell her property in California and put $1,500 into developing the discovery. However, when winter came on, Mrs. Ellis went to California and never had the opportunity to invest.

A man named Johnson Simmons of Oakland, California, who was stopping temporarily at Last Chance at the time, gave the following account:

Last Chance, California

“I recall the time when two miners were brought into Last Chance in the winter of 1857. Some men were out hunting deer when they found the two lying in the snow, where they were dying of cold and hunger. The one named Grosh never spoke after he was brought in. The miners carried them from the place where they were first found, as they were too weak to walk. Grosh, I think, lived about three days after being brought in. His stomach refused nourishment, and his legs were frozen. The other man we found pulled through, but they were obliged to amputate his feet. The miners then took him to Michigan Bar, where they kept him until spring and then raised a subscription to send him to his relatives in Canada. Before he left for Canada, he told me of his trip. He said their provisions gave out after passing Lake Bigler and their sufferings were terrible.

They had their provisions on a pack mule, but there was nothing but small twigs for him to eat, and he became so weak that they were obliged to kill him. After the mule was killed, he was cut up, and portions of his flesh roasted. The meat was lean, tough, and unsavory, and only their terrible hunger made it endurable. They ate their last cooked mule on the banks of the Truckee River, and, slinging as much of the roast meat as they could carry on their shoulders, they pushed on. They became so faint that they could no longer carry anything except their blankets, so they ate as much as they could and threw the rest away. At that point, Allen Grosh, who had kept his maps and assays through the journey, concluded to abandon them also, and so he tied them up into a piece of canvas and deposited them in the hollow of a large pine tree. McLoud said that he never saw the assays, Grosh being very close-mouthed regarding them. All that he knew of them was that they were high in silver, and from a conversation he overheard, he believed them high in the thousands. The tree in which they were deposited had blown down in the wind, having broken about twenty feet from the ground. Grosh told them that it was safer to select a tree of that kind than a standing one, liable in a storm to be uprooted. The hollow in the tree was quite small, and after depositing the records, he cut a mark on the tree with his knife and rolled a good-sized stone in front of the hollow. The next day there was a big snowstorm, and they finally threw away their blankets, as they were useless from the wet, and their matches were useless from the same cause. After the snowstorm, it turned colder, and for four days and nights, they wandered in the mountains, nearly dead and demented from exposure and hunger.

At night they could hear the howling of the wolves, but none were ever near enough to attack them, and once they crossed the track of a bear. They finally sank down with exhaustion near some rocks, and Grosh said he had rather die there than make any further effort. After giving themselves up for lost, they heard shots, and McLoud roused himself and went in the direction of the shots when he came on a party of miners hunting deer. He took the party to Grosh, only a few hundred yards away, and then sank down alongside him. The miners carried the two to Last Chance, a camp nearby, and there, Grosh died after a few days, never having been able to speak. Had he been able to speak, McLoud felt confident he would have made some statement relative to his discoveries.”

In the spring of 1858, Henry Comstock learned that Allen Grosh was dead and decided to take advantage of his acquired knowledge. The partner of Grosh claimed afterward that Comstock ransacked the cabin for papers and data and was thus enabled to relocate the ledge. It is not probable; however, such was the case, as the Grosh brothers did not trust him with anything, nor were they likely to leave anything in the cabin that would benefit him. After they left, he probably went over the ground where he had seen them prospecting and located the likeliest places.

The Record-Union newspaper of November 2, 1859, contained the following:

Henry T. Comstock

The tide is beginning to ebb slowly back. Parties of prospectors who went out yesterday and the day before are returning from the new diggings. I should think a dozen or fifteen have returned.

I am sorry for some of these mines and those who have founded their hopes upon them, but they do not appear to realize the anticipations of their friends. In sober truth, no one seems to have found the exact locality. I have conversed with a reliable person who hunted for them up hill and down dale a day and a half and not only lost the scent but got away from every trace of gold. He says after crossing the hills northeast from Six-Mile Canyon, he entered upon a rugged country where there was no quartz and where there were none of the other gold-bearing signs existing. He met or saw in all, nearly a hundred persons looking for new diggings, but could not hear of anyone who had struck them. There were reports that the real spot lies somewhere across the Carson River, in a direction southeast from here, and parties have gone in that direction.

The general belief appears to be that the new mines are a humbug of the first water. Nevertheless, I have this evening met and conversed with a man who professes to have come directly from the spot; his name is J. Clark, formerly of Placerville, California, and of late engaged in trading ventures to Ragtown and vicinity. He tells a moderate story and relates with an air of truthfulness what he professes to have himself seen. Instead of lumps, nuggets, and chispas, his discourse is of surface prospects yielding 10 cents to the pan, which is not enough, I fear, to satisfy the restless craving of the excited fortune-hunters. Ragtown, as all of you readers may not be aware, is about seventy miles in a northeasterly direction from this place, on the edge of the Great Desert, and is the first trading post that is reached by the overland emigration after crossing that “melancholy waste” and arriving on the frontier settlements of our State. This side of Ragtown are still two other deserts which the emigrants have to cross before reaching the Carson Valley proper.

Virginia City, Nevada Savage Works Mill, by Timothy H. O Sullivan, 1867.

When the miners came in the spring, Comstock was “on deck,” claiming everything, and in the same year, 1859, he was deeding ground to the newcomers and sold the Burning Moscow Mine, which seems to have been the second location on the Comstock, the Ophir Mine, being the first. The first deed given by Comstock, and probably the first ever recorded on the ledge, was for the paltry consideration of 40,andthenextonewasfor40, and the next one was for 40,andthenextonewasfor30. The Virginia Mine, or middle lead, commonly known as the Red Ledge, and lying parallel with and adjoining the Comstock on the west and the Black Ledge on the east, was brought into prominence in 1859 by the Burning Moscow discovery, which developed a body of ore as rich as any ever found in the district before or since. It contained native silver and free gold in large quantities. Among other locations made by Henry Comstock in the Virginia City district was one on the Red Ledge, officially recorded on June 27, 1859.

Adjoining this location, the Ketch and Baker Company and the McBee Mining Company claimed on March 23, 1859, that extended to the Cedar Ravine on the north and officially filed the claim.

The ground located by these three notices was then conveyed to the Iowa Mining Company, which was incorporated in 1862. This company’s early promoters were Louis McLane, Thomas Bee, William C. Ralston, Oliver Eldridge, W. F. Babcock, William Blanding, and E. A. Miller. These names would later become familiar in business circles on the Coast, and some are linked with the grandest enterprises in the Coast’s history.

On the other hand, Henry Comstock, who started these men at the beginning of riches, died poor. He sold out early, squandered his wealth, and left the area to spend the rest of his life trying to find another Comstock Lode.

After the Grosh brothers had passed from the scene of their labors, there was still nothing very tangible about the Comstock until Melville Atwood, a chemist and metallurgist residing at Grass Valley, made an assay of some rock brought from Nevada by a man named Walsh. This assay was from the first ton and a half of ore ever brought over the mountains from Nevada. The following are the original letters written by him regarding the find. He confounded the Truckee with the Carson River at the time of the writing.

Grass Valley, June 30, 1859.

My Dear Sir: On Monday morning, a miner, a friend of Walsh from Alpha, who had been locating a ranch near the Truckee River, came into our office with a sample of rock that he said was taken from the lead he had discovered near the Truckee River, and near which some miners had obtained large returns of gold.

I recognized it as a rich silver ore, and Walsh got him to divide the ground he had taken up into six shares, of which Walsh and self are to have one-sixth each. I made the assay on Tuesday and they proved to be so rich that Walsh and a friend of his left yesterday morning for the mine. In the assay made at Nevada City, California, they did not discover the silver. The mine (the Ophir) is in the Utah Territory, about 120 miles from this place. I have just heard that there is great excitement in Nevada City about it. I do hope Walsh will be in time to secure our ground. My assays gave from 15 to 20 percent. silver. I am much hurried and will write you again on Walsh’s return. He will bring 200 or 300 pounds of ore down with him. You may yet have something better than the sulphurets to ship to England. In great haste, yours most truly,

Melville Attwood. To Donald Davidson, Esq., San Francisco.

Attwood followed up with another letter a few weeks later:

Gold Hill Mines, Grass Valley, July 15, 1859.

Dear Sir: I have forwarded you through Wells, Fargo & Co. a small box containing samples of silver ore from the Ophir Mine referred to in my former letter. Mr. Walsh and Mr. Woodworth brought down about sixty pounds, and what I send you is some of the poorest of it. If you wet the pieces, I have marked you will note the black sulfate of silver.

Melville Attwood

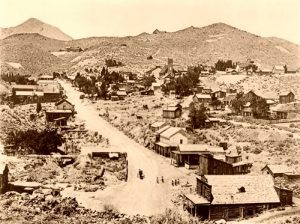

Silver City, Nevada, 1890

Some years after the Comstock Lode had become a heavy bullion producer, the heirs of the Grosh brothers tried to secure their rights on the Comstock by litigation. They employed Benjamin F. Butler, then the most noted lawyer in the United States, to prosecute the case.

He made a comprehensive examination of the matter. He stated to the litigants that there was no legal question about the absolute rights of the heirs to some of the most valuable ground on the Comstock. Still, he gave them the advice that the defendants were men so thoroughly entrenched in possession, and having unlimited money at their command, they would be able to buy up any jury that could be selected to try the case, and that, under the circumstances, the winning of such a case would be an impossibility.

The heirs of the Groshes wisely decided to drop the idea of attempting to wrest the big mines from the hands of William Sharon and the Bank of California.

The Comstock Lode made the reputation of Nevada as a mining state, and its record of an output of $700,000,000 has never been eclipsed.

It is common for the latter-day mining men operating in Nevada to compare present achievements in mining operations and output with the record of the past, and the founders of new camps frequently mention their holdings as “another Comstock.” However, the cold light of statistics bearing on their claims tells another story.

In closing, one must not forget to pay a deserved tribute to the sturdy prospector who blazes the path Midas is destined to tread later. He lives on hope and braves the manifold dangers of the mountain and desert to unearth and tap the treasure vaults of Nature.

He sows the harvest of wealth that others reap, and others realize the dreams that haunt the haze of his campfire. Yet, without heed of self, he presses on, leaving in his wake the pulsing life of populous cities and the hum of industries that spring into being from his wooing of the goddess of chance. The camp followers of the prospector dwell in the tabernacles of wealth while his bones rot in some unmarked and forgotten grave or bleach upon the sands of the pitiless waste he gave up his life to conquer.

Written by Sam P. Davis in 1912, compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Virginia City’s Main Street today is lined with historic buildings, Kathy Alexander.

Notes and Author: This article is primarily a tale told by Sam P. Davis in 1913, Chapter XIII, in Volume I of his series of books entitled The History of Nevada, Elms Publishing Co, Reno, Nevada. However, the article that appears here is far from verbatim. While the story remains essentially the same as initially published, heavy editing has occurred for spelling and grammar corrections, revisions for the modern reader, and updates to this historic tale. Samuel P. Davis was the owner and editor of the Carson Daily Appeal in (Carson City, Nevada. In addition to working as a journalist, he also wrote poetry and short stories published in magazines and a limited edition book entitled Short Stories and Poems. He also served as Nevada’s State Controller and published the three-volume The History of Nevada.

See the Comstock Foundation for History and Culture for more information and preservation.

Also See:

Pioche, Nevada – Wildest Town in the Silver State