Liberty Island and the Statue of Liberty – Legends of America (original) (raw)

The Statue of Liberty, photo by Ella Nobo, Legends of America’s granddaughter in training.

“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

The Statue of Liberty, Enlightening the World, was a gift of friendship from the people of France to the people of the United States and is a universal symbol of freedom and democracy. It was dedicated on October 28, 1886, designated as a National Monument in 1924, and restored for its centennial on July 4, 1986.

Today, Liberty Island is home to the Statue of Liberty. The island’s history, however, goes back much further than the Statue. In 994 A.D., the first people to occupy the island were Native Americans. These indigenous people were members of the Algonquian tribes and often visited Liberty Island because it contained numerous oyster beds, a primary food source. As a result, it was referred to as one of the three “Oyster Islands” in New York Harbor. In addition to harvesting shellfish, the Indians also hunted small animals on the island.

Indians fishing on the East Coast, 1590

Native Americans on Liberty Island may have spoken a Munsee dialect of the Algonquian Delaware. Other tribes that lived throughout the surrounding areas spoke the same dialect. These tribes included the Hackensack, Tappan, Esopus, and Warranawankong tribes (who lived west of the Hudson River); the Rechgawawank, Wiechquaeskeck, Sinsink, Kichtawank, Nochpeem, and Wappinger tribes (who lived in Eastern New York); the Canarsee tribe (who lived in what is now Brooklyn and Queens), and the Raritan tribe (who lived in what is now Staten Island). All of these tribes lived in relative harmony.

During this time, much of the west side, Upper New York Bay, contained large tidal flats that hosted vast oyster beds, a significant food source for the Indian population. Several islands were not completely submerged at high tide. Three of them, later known as Liberty, Ellis Island, and Black Tom, were given the name Oyster Islands by the settlers to the New Netherlands. The oyster beds would remain a significant food source for nearly three centuries. However, land-filling, overfishing, disease, and pollution essentially wiped out the local oyster. Landfilling also totally engulfed one island and brought the shorelines much closer to the others. Today, with dramatic improvements in water quality, efforts are being made in the area to launch oyster bed restoration projects.

In the 16th century, several Western European countries began searching for a passage to the Indian subcontinent – what is now South India. Europeans wanted access to expand their global trading network. Unfortunately, this search would forever change life for the Native American tribes who occupied the Oyster Islands. In 1606, the Dutch called on Henry Hudson to find a passage to the Indian subcontinent through the northeast region of the American continent. Although Hudson did not find his way to the Pacific Ocean, he arrived in New York harbor in 1609 and set up a Dutch colony along what is today the Hudson River.

Native Americans watch as Sir Henry Hudson arrives in New York.

In the early years of European settlement, the Native Americans and Europeans traded together.

In 1614, an exclusive trading agreement was made between the New York tribes and the Dutch settlers. The tribes gave the Dutch three years (or four voyages) of exclusive rights to collect furs and pelts on the land. In return, the Dutch gave the natives cast iron pots, iron axes, hoes, lead, knives, and other items.

By the mid-1600s, however, occupation, war, and disease forced the local tribes to move out of the area. They went both north and west of New York State. This resettlement made way for further European colonization.

In 1664, the English took possession of New Netherland from the Dutch, renaming it New York. Ownership of New York was valuable because of its location and status as a port of commerce and trade. The Oyster Island, now known as Liberty Island, was granted to Captain Robert Needham by the colonial Governor of New York, Richard Nicholls. Needham sold the island on December 23, 1667, to Isaac Bedloe – a Dutch colonist, merchant, and shipowner.

The Fall of New Amsterdam

Two years into Bedloe’s ownership of the island, the new colonial Governor, Colonel Francis Lovelace, confirmed Bedloe’s ownership of the land on the condition that Bedloe rename the island Love Island and allow persons facing civil charges to live there safely. In 1673, Bedloe died, and the Dutch colonists temporarily overthrew Governor Lovelace. Within a year, the English had regained control of New York, and Love Island was renamed Bedloe’s Island.

In 1732, Bedloe’s widow, Mary Bedloe Smith, who was facing bankruptcy, sold the island to New York merchants Adolph Philipse and Henry Lane. Though privately owned, the City of New York took control of the island, using it as a quarantine station, inspecting incoming ships for smallpox.

On January 22, 1746, Archibald Kennedy purchased the island and became the Collector and Receiver General of the Port of New York. By 1753, he had built a house and a lighthouse and began to promote a name change to “Kennedy Island.” He also advertised it for rent, as seen in this 1953 advertisement:

“To be Let. Bedloe’s Island, alias Love Island, together with the dwelling-house and lighthouse being finely situated for a tavern, where all kinds of garden stuff, poultry, etc., may be easily raised for the shipping outward bound, and from where any quantity of pickled oysters may be transported; it abounds with English rabbits.”

Two years later, however, in 1755, the City of New York again took control of the island for use as a quarantine station for smallpox.

On February 18, 1758, Bedloe’s Island was sold to the City of New York. In the following years, the city erected a pest house (a hospital for patients who suffer from infectious diseases) and leased land to tenants. During the American Revolution, the British government (which had occupied New York City) used Bedloe’s Island as an asylum for Tory refugees (American colonists loyal to Great Britain during the war). In April 1776, colonial forces attacked the island and burned the buildings.

The southern shore of Bedloe’s Island.

After the American Revolution, Bedloe’s Island continued to change ownership. From 1793 to 1796, the French (allies of the colonists during the Revolution) were ceded control of the island, appointed a Governor, and used the island as an isolation station. During this period, however, the young American government realized that Bedloe’s Island had value beyond its use as a quarantine station. Since the British had easily invaded New York with little resistance during the American Revolution, protecting New York became a top priority for the new government. With its clear view of the entrance to New York Harbor and New York City, Bedloe’s Island had great strategic value as a defense post.

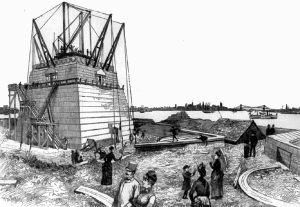

The French were asked to leave the island, and in 1796, ownership was transferred to the State of New York. By 1807, several forts were constructed (or rehabilitated) throughout New York Harbor to protect New York City from invasion. On Bedloe’s Island, an eleven-point star-shaped fort, initially known as the “Works on Bedloe’s Island,” was constructed. In 1814, this fort was renamed Fort Wood by New York Governor Daniel D. Tompkins in memory of Eleazer D. Wood, an army hero killed in action at Fort Erie during the War of 1812.

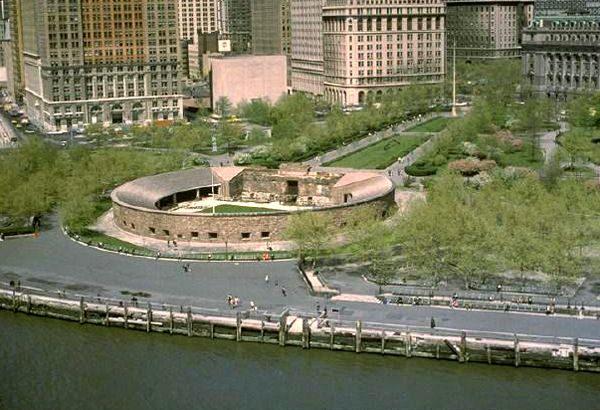

Castle Clinton Today by the National Park Service.

Other newly erected or refurbished forts along New York harbor included Fort Hamilton in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island, Fort Gibson on Ellis Island, Fort Clinton in Manhattan (now known as Castle Clinton), and Fort Columbus and Fort Williams on Governor’s Island. In later years, many of these forts were used as recruiting and ordnance depots.

In 1834, an interstate agreement between New York and New Jersey placed Bedloe’s Island within New York. New Jersey, however, retained rights to waters and all submerged land surrounding the island.

Fort Wood served as an ordnance depot between 1851 and 1876. During the first year, about 600 men were stationed at the fort, which was half-covered with tents and very crowded. By 1852, soldiers were moving around the harbor, and Fort Wood was almost deserted. Occupation picked up during the Civil War, beginning in 1861, when the fort served as a depot. The army remained active on Bedloe’s Island until 1937.

After the Union won the Civil War in 1865, a French political intellectual and anti-slavery activist named Edouard de Laboulaye proposed that a statue representing liberty be built for the United States. This monument would honor the United States’ centennial of independence and friendship with France. French sculptor Auguste Bartholdi supported Laboulaye’s idea and, in 1870, began designing the statue of “Liberty Enlightening the World.”

While designing the Statue, Bartholdi traveled to the United States in 1871. During the trip, he selected Bedloe’s Island as the site for the Statue. Although the island was small, it was visible to every ship entering New York Harbor, which Bartholdi viewed as the “gateway to America.”

In 1876, French artisans and craftsmen began constructing the Statue in France under Bartholdi’s direction. The arm holding the torch was completed in 1876 and shown at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. The head and shoulders were completed in 1878 and displayed at the Paris Universal Exposition. The entire Statue was completed and assembled in Paris between 1881 and 1884. Also, in 1884, construction on the pedestal began in the United States.

After the Statue was presented to Levi P Morton, the U.S. minister to France, on July 4, 1884, in Paris, it was disassembled and shipped to the United States aboard the French Navy ship Isère. The Statue arrived in New York Harbor on June 17, 1885, and was met with great fanfare. Unfortunately, the pedestal for the Statue was not yet complete.

Once the pedestal was completed in 1886, a fearless construction crew – many of whom were new immigrants- reassembled the Statue with surprising speed. The first piece of the Statue to be reconstructed was Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel’s iron framework. The rest of the Statue’s elements followed without the use of scaffolding – steam-driven cranes and derricks hoisted up all construction materials. In order to sculpt the Statue’s skin, Eiffel used the repoussé technique developed by Eugene Viollet-le-Duc. This technique molds lightweight copper sheets by hammering them onto the Statue’s hallowed wooden framework. The last section to be completed was the Statue of Liberty’s face, which remained veiled until the Statue’s dedication. Although Fort Wood remained on Bedloe’s Island, it was not an obstacle in the Statue of Liberty’s design, construction, or reassembly. Instead, the star-shaped structure became a part of the Statue’s base, with the pedestal sitting within its walls.

The Statue of Liberty was unveiled.

On October 28, 1886, the “Liberty Enlightening the World” statue was officially unveiled. The day’s wet and foggy weather did not stop a million New Yorkers from turning out to cheer for The Statue of Liberty. Parades on land and sea honored the Statue while flags and music filled the air, and the official dedication took place beneath the colossus “glistening with rain.” When it was time for Bartholdi to release the tricolor French flag that veiled Liberty’s face, a roar of guns, whistles, and applause sounded.

At the time of its dedication in 1886, President Grover Cleveland placed the Statue of Liberty under the administration of the U.S. Lighthouse Board since it was categorized as a federal lighthouse. Although the Statue’s torch had been electrified for use as a lighthouse in 1886, the Statue had not been designed for this purpose and was not very effective. In 1901, the Statue was transferred to the U.S. Department of War.

When the National Park Service was granted control of the island in 1937, they decided to redesign it so that its landscape complemented the Statue of Liberty. This was the first time the Statue and Bedloe’s Island would be combined into a unified design. Norman T. Newton, a landscape architect for the National Park Service, created a master plan to transform Bedloe’s Island. Newton’s plan was intended to attract visitors to the island and provide a proper setting for the Statue, now a national monument. Newton’s plans called for army buildings to be demolished and for lawns and promenades to be created in their place. This plan was intended to heighten the island’s appeal and provide a beautiful backdrop for the Statue.

In the spring of 1937, several New Deal programs, including the Public Works Administration (or PWA), under the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt, enabled the National Park Service to begin implementing Norman T. Newton’s master plan. In 1939, the National Park Service began refurbishing the Statue and additional structures on the island. Work continued on the island until the beginning of World War II. When the United States entered the war in 1941, resources were diverted to the war effort from the public works projects, and work on the island was halted. In 1948, following public complaints about the shabby condition on the island, Congress appropriated $110,000 for the Statue of Liberty. With renewed funding, workers tore down the abandoned and dilapidated army structures, planted trees, and paved pathways.

Statue of Liberty Pedestal.

Work on the island was completed by 1957. The renovation marked a turning point for Bedloe’s Island because it transformed it into a park. To commemorate this event, Bedloe’s Island was renamed Liberty Island in 1956 through a joint resolution in Congress and signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

In 1965, a presidential proclamation added nearby Ellis Island, an icon of American immigration, to the Statue of Liberty National Monument. From 1892 to 1954, over 12 million immigrants passed through Ellis Island.

In 1982, four years before the Statue’s centennial anniversary, President Ronald Reagan appointed Lee Iacocca, the Chairman of Chrysler Corporation, to head the Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island Foundation. The Foundation was created to lead the private sector effort and raise funds to renovate and preserve the Statue for its centennial in 1986. The Foundation worked with the National Park Service to plan, oversee, and implement this restoration.

A team of French and American architects, engineers, and conservators came together to determine what was needed to ensure the Statue’s preservation into the next century. In 1984, scaffolding was erected around the exterior of the Statue, and construction began on the interior. Workers repaired holes in the copper skin and removed layers of paint from the interior of the copper skin and internal iron structure. They replaced the rusting iron armature bars with stainless steel bars (which joined the copper skin to the Statue’s internal skeleton). The flame and upper portion of the torch had been severely damaged by water and were replaced with a replica of Bartholdi’s original torch. The torch was gilded according to Bartholdi’s original plans.

The restoration was completed in 1986, and the Statue’s centennial was celebrated on July 4 with fireworks and fanfare. The next day, a new Statue of Liberty exhibit opened at the pedestal’s base.

Today, Liberty Island and nearby Ellis Island are part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument in New York Harbor. The monument can only be visited by using the Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island Ferry system. Private vessels are not allowed to dock at Liberty and Ellis Islands. Ferries depart from Battery Park in New York City and Liberty State Park in New Jersey.

Ellis Island, New York.

Visitors can enjoy the 14.7-acre exterior grounds of Liberty Island, brochures, and a video at the Information Center regarding the story of the Statue of Liberty. Audio tours and guided ranger tours are also available. Located less than a mile north of Liberty Island, Ellis Island is an included stop for those visiting the Statue of Liberty National Monument. Here, the main building of this once busiest port of entry has become a museum and is one of the country’s most famous historic sites.

More Information:

Statue of Liberty National Monument

Liberty Island

New York, New York 10004

212-363-3200

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2024.

Also See:

Ellis Island – Island of Hope & Tears

Immigration – The First Gateway

National Parks, Monuments & Historic Sites

Primary Source: National Park Service