The Invasion of Oklahoma – Legends of America (original) (raw)

The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 was the first land rush into the Unassigned Lands of present-day Oklahoma. Touch of Color by LOA

By James Cox in 1903

Oklahoma, the youngest of our Territories, is also the most interesting in many respects. Many people confound Oklahoma Territory with the Indian Territory. Still, the two are separate and distinct, the former enjoying Territorial Government. At the same time, the latter is in a very strange condition regarding making and enforcing laws.

Within a few years, Oklahoma was a part of what was then the ” Indian Territory.” Now it has been separated from what may be described as its original parent and is entirely distinct.

It contains nearly 40,000 square miles and has a population of about a quarter of a million, exclusive of about 18,000 Indians. It contains more than twice as many people in the square mile as many Western States and Territories. It is in a condition of thriving prosperity, which is extraordinary when its extreme youth as a Territory is considered.

In 1888, Oklahoma was the largest single body of unimproved land capable of cultivation in the Southwest. Indian tribes nominally farmed it, but the natural productiveness of the soil, and the immense amount of land at their disposal, cultivated habits of idleness, and there was a grievous and even sinful waste of fertility. To the south was Texas, and on the north Kansas, both rich, powerful, and wealthy states. The Indian possessions lying between disturbed the natural growth and trend of the empire.

Seen from car windows only, the country appeared inviting to the eye. From reports of traders, it was known to have all the elements of agricultural wealth. And this made the land-hungry man hungrier.

The era of the “boomer” began, and the “boomer” did not stop until he had inserted an opening wedge in the shape of the purchase and opening to settlement of a vast area right in the heart of the prairie wilderness. When the first opening occurred, it seemed like the supply would be more than the demand. Not so. Every acre — good, bad, or indifferent –was gobbled up, and, like as from an army of Oliver Twists, the cry went up for more. Then the Ioway and Potawatomi reservations were placed on the market. They lasted a day only, and the still unsatisfied crowd began another agitation. Resultant of this, a third bargain-counter sale took place. The big Cheyenne and Arapaho country was opened for settlement. Immigrants poured in, and now every quarter-section that is tillable there has its individual occupant and owner.

But still, on the south border of Kansas, a landless and homeless multitude camped. They looked longingly over the fertile prairies of the Cherokee Strip country, stirred the campfire embers emphatically, and sent another dispatch to Washington asking for a chance to get in. Congress heard at last, and the congestion was relieved in the fall of 1893.

The scenes attending the wild scramble from all sides of the Strip are a matter of history and do not require repetition. Five million acres were quickly taken by 30,000 farmers.

The old proverb or adage states that the man who makes two blades of grass grow where one grew before is a public benefactor would seem to proclaim that Oklahoma is peopled with philanthropists for the sturdy pioneers. They braved hardship and ridicule to obtain a foothold in this promised land and have completely changed the country’s appearance in five or six years. A larger proportion of ground in this youthful Territory shows that it is a sturdy infant. It is doubtful whether there has been more economy in land in any part of the United States or a more rapid use of opportunities bountifully provided by nature.

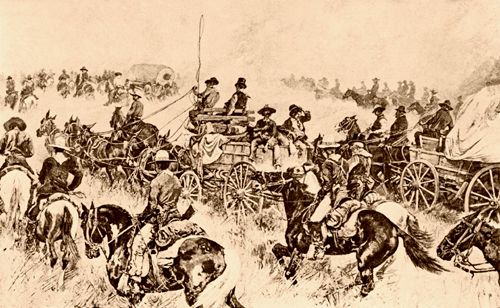

Boomers entering Oklahoma Territory, 1905, John D. Morris and Company.

Truth is often much stranger than fiction, and the story of the invasion of Oklahoma reads like one long romance. Many men lost their lives in the attempt, some few dying by violence, and many others succumbing to disease brought about by hardship.

Many of the men who started the agitation to have Oklahoma opened for settlement by white citizens are still alive, and some of them have had their heart’s desire fulfilled and now occupy small homes they have built in some favorite nook and corner of their much loved, and at one time grievously coveted, country.

Oklahoma came into the possession of the Seminole Indians by the ordinary process and remained their alleged home until about thirty years ago. In 1866, the country was ceded to the United States Government for consideration, and in 1873, it was surveyed by Federal officers, and section lines were established according to law.

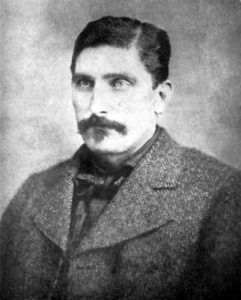

Captain David L. Payne

It was the natural presumption that this expense was incurred with a view to the immediate opening of the Territory for settlement. For various reasons, more or less valid and more or less the result of the influence and possible corruption, the actual opening of the country was deferred for more than twenty years after its cession to the United States Government. In the meantime, it occupied a peculiar condition. Immense herds of cattle were pastured on it, and bad men and outlaws from various sections of the country awoke reminiscences of biblical stories about cities of refuge by squatting upon it, making a living by hunting and indifferent agriculture, and resting securely from molestation from officers of the law.

Captain Payne and several determined men organized themselves into colonies to remedy this anomaly and secure homes for themselves and their families in what was reported to be one of the most fertile tracts in the world. There has always been a mania for new land. Many people are never happy unless they keep pace with the invasion of civilization into hitherto unknown and unopened countries. Many who joined the Payne movement were doubtless roving spirits of this character. Still, most of them were bona fide home-seekers, who believed as citizens of this country, they had a right to quarter-sections in the promised land and were determined to enforce those rights.

No matter, however, what were the motives of the “boomers,” as they were called from the first, it is certain that they went to work in a business-like manner, planned a regular invasion, and formed several colonies or small armies for the purpose.

We will follow the fortune of one of these colonies to show what extraordinary difficulties they went through and how much more there is in heaven and earth than is dreamt of in our humdrum philosophy. On the southern line of Kansas, the town of Caldwell was the camp from which the first colonists started. It consisted of about 40 men and about 100 women and children. Each family provided itself with such equipment and conveniences as the scanty means at its disposal made possible. A prairie schooner, or a wagon with a covering to protect the inmates from the weather and secure a certain amount of privacy for the women and children, was an indispensable item.

When the advance was made, there were forty such covered wagons, each drawn by a pair of horses or mules and each containing such furniture as the family possessed. The more fortunate ones also had specific materials to build the little hut in the wagons, which was to be their home until they could earn enough to build a more pretentious residence.

Eyewitnesses describe the starting of the colony as one of the most remarkable sights ever witnessed. The wagons advanced in single file, and some few of the men rode on horseback to act as advance guides to seek suitable camping grounds and to protect the occupants of the wagons from attack. In some cases, one or two cows were attached by halters to the rear of the wagons, and several dogs entered heartily into the spirit of the affair. The utmost confidence prevailed, and hearty cheers were given as the cavalcade crossed the Kansas State line and commenced its long and dreary march through the rich bluegrass of the Cherokee Strip.

The journey before the home-seekers was about 100 miles, and at the slow progress they were compelled to make, it was a long and arduous task. Some women were a little nervous, but most had thoroughly fallen in with the general feeling and were enthusiastic. The food they had with them was sufficient for immediate needs, and when they camped for the night, the party’s younger members generally succeeded in adding to the larder by hunting and fishing.

People line up for the Oklahoma Land Run in Caldwell, Kansas.

We have all heard of invading armies being allowed to march unmolested, only to be treated with additional severity upon arriving at the enemies’ camp. So it was with the colonists. They got through very little difficulty, and no one took the trouble to interfere with their progress. Men who had been in the promised land for the purpose had located a suitable spot for forming the proposed colony, and here the people were directed. One of the party had some knowledge of land laws, and after a long hunt, he succeeded in locating one of the section corners established by the recent Government survey. This being done, quarter-sections were selected by each of the newcomers, and work commenced with a will. Tents and huts were put up as rapidly as possible, and before a week had passed, the newcomers were pretty well settled. They even selected a townsite and built castles of the most remarkable character in the air.

That they were monarchs of all they surveyed seemed obvious, and for some weeks, their right there was none to dispute. Then by degrees, the cowboys herding cattle in the neighborhood began to drop hints of possible interference. While these suggestions were being discussed, a company of United States troops suddenly appeared. With very little explanation, they arrested every man in the colony for treason and conspiracy and proceeded to drive the colonists out of the country.

The men were compelled to hitch up their horses, and, succumbing to the force of numbers, the colonists sadly and wearily advanced to Fort Reno, where they were turned over to the authorities. After being kept in confinement for five days, they were released and told to return to Kansas as rapidly as possible. Government officials saw that the order was carried out and left the colonists to themselves.

The men lost no time in making up their minds to organize a second attempt to establish homes for their families, and once more, they made the march. A bitter disappointment awaited them, for they found that their cabins had all been destroyed, and they had to commence work over again. This they did, and they had scarcely got themselves comfortable when another small detachment of troops arrived to turn them out. The men were tied using ropes to the tail-ends of wagons and driven like cattle across the prairie to the military fort. For a third time, they conducted an invasion, and for the third time, they were attacked by Government troops.

However, a spirit of determination had come over the men in the interval, and an attempt was made to resist the onslaught of the soldiers. The Lieutenant in charge was astonished at the attitude assumed and did not care to assume the responsibility of ordering his men to fire. Many of the colonists were well-armed and were undoubtedly crack shots. He, accordingly, adopted more diplomatic measures and, by establishing somewhat friendly relations, got into close quarters with the settlers. A rough and tumble fight with fists soon afterward resulted, and the settlers’ hard fists and brawny arms proved too much for the regulars, who were, for the time, being driven off.

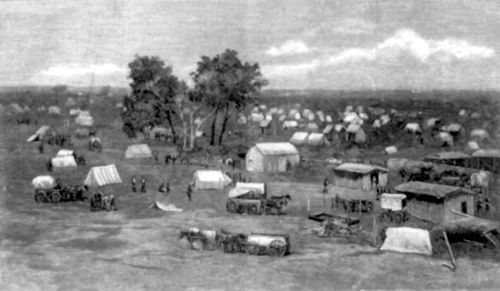

Oklahoma city Founding

The boomers’ victory resulted in the sending of 600 soldiers to dislodge them, and it was impossible to resist such a force as this. The colonists yielded with the best grace and sadly deserted the homes they had tried so hard to build up. Some of the men were imprisoned for the action they had taken, and the colony, for a time, was utterly broken up. Several others followed the example set, and a conflict not particularly creditable to the Government went on for some years. No law was discovered to punish the boomers and thus end the invasions. All that could be done was to drive the families out as fast as they went in, a course of action far more calculated to excite disorder than to quell it.

Sometimes the soldiers displayed a great deal of forbearance and even went out of their way to help the women and children and reduce their sufferings to the smallest possible point. Again, they were sometimes unduly harsh, and more than one infant lost its life from the exposure the evictions brought about. The soldiers by no means relished the work given them, and many complained bitterly that it was no part of their duty to fight women and babies. Still, they were compelled to obey orders and ask no questions.

While the original colonists, or boomers, gained little or nothing for themselves by the hardships they insisted on encountering, they brought about the opening for settlement of Oklahoma. About the year 1885, it began to be generally understood that the necessary proclamation would be issued. Home hunters from all parts of the country began to set out on a journey, varying in length from a few hundred to several thousand miles. The Kansas border towns on the south were made the headquarters for the home-seekers, and as they arrived at different points, they were astonished to find that others had got there before them. In the neighborhood of Arkansas City, mainly, there were large settlements of boomers, who, from time to time, made efforts to enter the promised land in advance of the proclamation, only to be turned back by the soldiers who were guarding every trail. The majority of the newcomers thought it better to obey the law. With their wagons for their homes, these settled down and sought work to maintain their families until the proclamation was issued and the country opened to them.

It was a long and dreary wait. The children were sent to school, the men obtained such employment as was possible, and life went on peacefully in some of the most peculiar settlements ever seen in this country. Finally, the Springer Bill was passed, and the speedy opening of at least a portion of Oklahoma was assured. The news was telegraphed to the four winds of heaven; where there had been one boomer before, there were soon fifty or a hundred. In the winter of 1888, various estimates were made regarding the number of people awaiting the President’s proclamation, and the total could not have been less than 50,000 or 60,000. Finally, the long-looked-for document appeared, and Easter Monday [April 22], 1889, was named as the date the section of Oklahoma included in the bill was to be declared open. There was a special proviso that anyone entering the promised and mysterious land before noon on the day named would be forever disqualified from holding land in it. Accordingly, the opening resolved itself into a race, to commence promptly at high noon on the day named.

Seldom has such an amazing race been witnessed in any part of the world. The principal townsites were on the line of the Santa Fe Railroad, and those who were seeking town lots crowded the trains, which were not allowed to enter Oklahoma until noon. All available rolling stock was brought into requisition for the occasion, and provision was made for hauling thousands of home-seekers to the towns of Guthrie and Oklahoma City, as well as to intervening points. Before daylight on the morning of the opening, the approaches of the railway station at Arkansas City were blocked with masses of humanity, and every train was thronged with town boomers or with people in search of free land or town lots.

The author was fortunate to secure a seat on the first train, which crossed the Oklahoma border and arrived at Guthrie before 1 o’clock on the opening day. It was presumed that the law had been enforced and that we should find nothing but a land office and a few officials on the townsite.

But such was far from being the case. Hundreds of people were already on the ground. The town had been platted out, streets located, and the best corners seized in advance of the law and the proclamation regulations.

There was no time to argue with points of law or order. Those who got in advance of the law were determined, and their number was so great that they relied on the confusion to evade detection. One of their numbers told an interesting story to the writer concerning the experience he had gone through. He had slipped into Oklahoma before the opening, carrying with him enough food to last him for a few days. He found a hiding place in the creek bank, and there laid until a few minutes before noon on opening day. When his watch and the sun both told him that it lacked, but a few minutes of noon, he emerged from his hiding place to leisurely locate one of the best corner lots in the town. To his chagrin, he saw men advancing from every direction, and he was made aware of the fact that he had no patent on his idea, which had been adopted simultaneously by several hundred others. He secured a good lot for himself and sold it before his disqualification on account of being too “previous” in his entry was discovered.

As each train unloaded its immense crowds of passengers, the scene must always baffle description. The townsite was on rising ground, and men and even women sprang from the moving trains, falling headlong over each other and then rushing uphill as fast as their legs would carry them, in the mad fight for town lots free of charge. The townsite was entirely occupied within half an hour, and the surrounding country in every direction was appropriated for additions to the main “city.” Before night there were at least 10,000 people on the ground, many estimates placing the number as high as 20,000.

Some brought blankets and provisions, and these passed a comparatively comfortable night. Thousands, however, had no alternative but to sleep on the open prairie, hungry, as well as thirsty. The water in the creek was scarcely fit to drink, and the railroad company had to protect its water tank by force from the thirsty adventurers and speculators.

The night brought additional terrors. There was no danger of wild animals or snakes, for the stampede of the previous day had probably driven every living thing miles away, with the solitary exception of ants, which, in armies ten thousand strong, attacked the trespassers. By morning several houses had been erected, and the arrival of freight trains loaded with provisions not only enabled thoughtful caterers to make small fortunes but also relieved the newcomers of much of the distress they had been suffering. The streets were well defined within a week, and houses were being built in every direction. Within six months, several brick buildings were erected and occupied for business and banking purposes.

Guthrie Land Office

The process of building up was one of the quickest on record, and Guthrie, like its neighbor on the south, Oklahoma City is today a large, substantial business and financial center. Those of our readers who crossed Oklahoma by rail, even as late as the winter of 1888, will remember that they saw nothing but open prairie with occasional belts of timber. There was not so much as a post to mark the location of either of these two large cities, nor was there a plow line to define their limits.

In no other country in the world could results such as these have been accomplished. The amount of courage required to invest time and money in a prospective town in a country hitherto closed against white citizens is enormous, and it takes an American, born and bred, to make the venture.

The Oklahoma cities are not boom towns, laid out on paper and advertised as future railroad and business centers; they have been practical, useful trading centers from the first moment of their existence. Every particle of growth they have made has been of a permanent and lasting character.

But if the race to the Oklahoma town sites was interesting, the race to the homesteads was sensational and bewildering. Around the coveted land, anxious, determined men were waiting for the word “Go” to rush forward and select a future home. In some instances, the race was made in the wagons. Still, in many cases, a solitary horseman acted as a pioneer and galloped ahead to secure prior claim to a coveted, well-watered quarter-section. Shortly before the noon hour, several boomers on the northern frontier made an effort to advance despite the protests of the soldiers on guard. These latter were outnumbered ten to one and could not attempt to hold back the home-seekers by force. Seeing this fact, the young Lieutenant in charge addressed a few pointed sentences to the would-be violators of the law. He knew most of the men personally and was aware that several were old soldiers. Addressing these especially, he appealed to their patriotism and asked whether it was logical for men who had borne arms for their country to combine to break the laws, which they had risked their lives to uphold. This appeal to the loyalty of the veterans had the desired effect, and what threatened to be a dangerous conflict resulted in a series of hearty hand-shakes.

A mighty shout went up at noon, and the deer, rabbits, and birds, which for years had held undisputed possession of the promised land, were treated to a surprise of the first water. Horses that had never been asked to run before were now compelled to assume a gait hitherto unknown to them. Wagons were upset, horses were thrown down, and all sorts of accidents happened. One man, who had set his heart on locating on the Canadian River near the Old Payne Colony, rode his horse in that direction and urged the beast on to further exertions until it could scarcely keep on its feet. Finally, he reached one of the creeks running into the river. The tired animal just managed to drag its rider up the steep bank of the creek, and it then fell dead. Its rider had no time for regrets. He still had four or five miles to cover, and he commenced to run as fast as his legs would carry him. His over-estimate of his horse’s powers of endurance, and his under-estimate of the distance to be covered, lost him his coveted home, for when he arrived, a large colony had got in ahead of him from the western border, and there were two or three claimants to every homestead.

In other cases, there were neck and neck races for favored locations, and sometimes it would have puzzled an experienced referee to determine who the winner of the race was. Compromises were occasionally agreed to, and although there was a good deal of bad temper and recrimination, there was very little violence. The men whose patience had been sorely taxed behaved themselves admirably, earning the respect of the soldiers who were on guard to preserve order. The excitement and uproar were kept up long after nightfall. In their feverish anxiety to retain possession of the homes for which they had waited and raced, hundreds of men stayed up all night to continue the work of hut building, knowing that nothing would help them so much in pressing their claims for a title as evidence of work on bona fide improvements. They kept on day after day, and, late in the season as it was, many of the newcomers raised a good crop that year.

The opening of other sections of the old Indian Territory, now included in Oklahoma, took place two or three years later when the scenes we have briefly described were repeated. Today, Oklahoma extends right up to the southern Kansas line, and the Cherokee Strip, on whose rich bluegrass hundreds of thousands of cattle have been fattened, is now a settled country, with at least four families to every square mile, and with several thriving towns and even large cities. At present, the question of Statehood for the youngest of our Territories is being actively debated. No one disputes that the population and wealth are large enough to justify the step. The only question at issue is whether the whole of the Indian Territory should be included in the new State or whether the lands of the so-called civilized tribes should be included should be excluded.

The lawlessness that has prevailed in some portions of the Indian Territory is a strong argument in favor of opening up all the lands for settlement. At present, the Indians own immense tracts of land under very peculiar conditions. Many white men, many of them respectable citizens, and many of them outlaws and refugees from justice, have married fair Cherokee, Choctaw, and Creek girls. While not recognized by the heads of the tribes, these men can draw from the Government, in the names of their wives, the large sums of money from time to time distributed. Advocates of Statehood favor the allotment to each Indian of his share of the land and the purchase by the Government of the immense residue, which could then open for settlement.

Some of the Indians have assumed the manners, dress, virtues, and vices of their white neighbors, in which case they have generally dropped their old names and assumed something reasonable in their place. But many of the red men who adhere to tradition and object to innovation still stick to the names given them in their boyhood. Thus, in traveling across the Indian Territory, Indians with such names as “Hears-Something-Everywhere,” “Knows-Where-He-Walks,” “Bear-in-the-Cloud,” “Goose-Over-the-Hill,” “Shell-on-the-Neck,” “Sorrel Horse,” “White Fox,” “Strikes-on-the-Top-of-the-Head,” and other equally far-fetched and ridiculous terms and cognomens.

Everyone has heard of Chief Rain-in-the-Face, a characteristic Indian whose virtues and vices have both been greatly exaggerated from time to time. A picture is given of this representative of a rapidly decaying race, and of the favorite pony upon which he has ridden thousands of miles, and which in its early years possessed powers of endurance far beyond what anyone who has resided in countries removed from Indian settlements can have any idea or conception of.

James Cox, 1903. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

About the Author: The Invasion of Oklahoma, written by James Cox, was a chapter in his book My Native Land, published in 1903 and now in the public domain. Cox wrote several other books around this same time.

Also See: