Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – Independence Begins – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Skyline, courtesy Wikimedia.

George Washington’s inauguration at Philadelphia by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris 1947.

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the most populous city in Pennsylvania and the second-most populous city in the Northeast Boston-Washington corridor and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City.

The city is known for its extensive contributions to United States history, especially during the American Revolution. It served as the nation’s capital until 1800 and maintained contemporary influence in business, industry, culture, sports, and music.

Philadelphia is the nation’s sixth-most populous city, with a population of 1,603,797 as of the 2020 census, and is the urban core of the larger Delaware Valley Metropolitan area, the nation’s seventh-largest and one of the world’s largest metropolitan regions consisting of 6.245 million residents in the metropolitan statistical area and 7.366 million residents in its combined statistical area.

The First Inhabitants

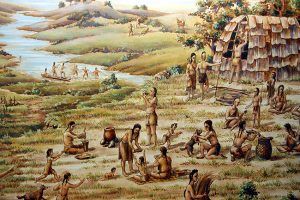

Lenape Indians Scene.

Before the arrival of Europeans in the early 17th century, the Philadelphia area was home to the Lenape Indians in the village of Shackamaxon. They were also called the Delaware Indians, and their historical territory was along the Delaware River watershed of western Long Island and the Lower Hudson Valley. They belonged to the Algonquian linguistic stock and, according to their legends, had migrated eastward from the country beyond the Mississippi River.

The Lenape nation was divided into three main tribal groups –the Munsee, Unami, and Unalachtigo. Philadelphia’s history is connected chiefly with the Unami (or “Turtle”) tribe of Lenape, though the Susquehannock and Shawnee also figured in the city’s early history.

The Unami had large heads and faces, and their noses were sharply hooked. Mainly a sedentary and agricultural people, they lived on maize, fish, and game. Men of the tribe dressed in breech clout, leggings, and moccasins, with skin mantle or blanket thrown over one shoulder. Their heads were shaved or clipped, except for a scalp lock generously pomaded with bear’s grease and adorned with ornaments. The women garbed themselves in leather shirts or bodices with skirts of the same material. They wore their hair plaited, the long tails falling over their shoulders.

Before the Dutch and Swedes arrived, the Indians lived in birch bark lodges. A more sturdy log hut appeared later and was probably copied from the whites, although Iroquoian people lived in log dwellings before white contact.

Not long before William Penn arrived in the New World, the Shawnee moved northward to the Wyoming Valley and then to western Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Susquehannock Warrior

The Susquehannock from Maryland, known as “Black Minquas” to the Swedes, had preceded them and were well known to the early settlers. The Susquehannock, waging bitter warfare with the Iroquois Confederacy, were driven from their Pennsylvania strongholds early in white colonization.

The Iroquois occasionally fought the Lenape. Most Lenape were pushed out of their Delaware homeland during the 18th century by expanding European colonies, exacerbated by losses from intertribal conflicts and diseases introduced by Europeans, mainly smallpox. The American Revolutionary War and the United States’ independence pushed them further west. In the 1860s, the United States government sent most of the remaining Delaware Indians in the eastern United States to the Indian Territory of present-day Oklahoma and surrounding territories under the Indian removal policy.

Exploration & Settlement

Europeans came to the Delaware Valley in the early 17th century. The first settlements were founded by Dutch colonists, who built Fort Nassau on the Delaware River in 1623 in what is now Brooklawn, New Jersey. The Dutch considered the entire Delaware River Valley part of their New Netherland colony.

As early as 1634, two Englishmen, Thomas Young, and Robert Evelyn, journeyed as far north on the Delaware River as the present site of Philadelphia. They built a small fort at the mouth of the Schuylkill River but remained there for only five days. The following year, by order of the Governor of Virginia, an expedition under Captain George Holmes attempted to seize Fort Nassau on the New Jersey side. However, the Dutch, who captured Holmes and sent him in chains to New Amsterdam, frustrated the attempt.

In 1638, Swedish settlers led by renegade Dutch established the colony of New Sweden at Fort Christina, located in present-day Wilmington, Delaware, and quickly spread out in the valley.

Schuylkill River, courtesy Wikipedia.

In 1641, about 60 Puritans from New Haven, Connecticut, went up the Delaware River to settle permanently at the mouth of the Schuylkill River. The Puritans erected a blockhouse, but before long, the Dutch burned it to the ground, and the colonizers were sent to New Amsterdam.

In 1644, New Sweden supported the Susquehannock in their war against Maryland colonists.

In 1648, the Dutch built Fort Beversreede on the west bank of the Delaware River, south of the Schuylkill River near the present-day Eastwick section of Philadelphia, to reassert their dominion over the area. The Swedes responded by building New Korsholm, named after a town in Finland with a Swedish majority.

In 1655, a Dutch military campaign led by New Netherland Director-General Peter Stuyvesant took control of the Swedish colony, ending its claim to independence. The Swedish and Finnish settlers continued to have their own militia, religion, and court and enjoyed substantial autonomy under the Dutch.

On August 27, 1664, an English fleet captured the New Netherland colony.

At last, after long years of claims and counterclaims, voyages of exploration, and attempts at colonization, came the Treaty of Breda in 1667, whereby England gained possession of the territory now contained in the states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and New York. Vital changes in affairs of the New World were linked intimately with developments in the Old.

After Nicolls, Colonel Francis Lovelace governed on the Delaware River from 1667 to 1673; the Dutch gained ascendancy in 1673 following the fortunes of a fresh war overseas. They maintained this position for only a year when Peter Alrichs was deputy governor of the Colonies on the west side of the Delaware River. With the Treaty of Westminster in 1674, the English were masters again on this side of the Atlantic.

By 1676, James West had established a shipyard on the site bounded by Vine, Water, Callowhill Streets, and Christopher Columbus Boulevard. Over the next century, he, his family, and others built a large maritime complex.

Four years later, in 1678, the English ship Shield sailed up the Delaware River, passing the Indian place called Coaquannock under a thin mantle of snow on the river’s western bank. The site of Philadelphia was an almost unbroken wilderness then, except for a few scattered clearings and an occasional log cabin.

The Shield, bound upriver for the new settlement of Burlington, New Jersey, tacked close into shore — so close that some of the riggings scraped against branches of trees lining the water’s edge. One of the crew gazed in awe at the broad, flat forests stretching away from the peaceful Delaware River, then turned to a shipmate and exclaimed: “Here is a fine place for a town!”

William Penn

In 1681, in partial debt repayment, King Charles II of England granted William Penn a charter for what would become the Pennsylvania colony. Despite the royal charter, Penn bought the land from the local Lenape to establish good terms with the Native Americans and ensure peace for the colony. Penn made a treaty of friendship with Lenape Chief Tammany under an elm tree at Shackamaxon in what is now the city’s Fishtown neighborhood. After receiving his charter for Pennsylvania from Britain’s King Charles II, William Penn embarked upon a “holy experiment,” the founding of a colony predicated on the principles of tolerance and justice, including the rights of freedom of religion and trial by jury. At Philadelphia, Penn endeavored to create an ideal city that would not corrupt his holy experiment.

Philadelphia’s Founding

Philadelphia was founded in 1682. As a Quaker, William Penn had experienced religious persecution and wanted his colony to be where anyone could worship freely. This tolerance, which exceeded that of other colonies, led to better relations with the local Native American tribes and fostered Philadelphia’s rapid growth into America’s most important city.

The Free Society of Traders was incorporated, with a capital stock of £10,000 to develop the Province. Penn sold the society 20,000 acres in a single tract. The company did not prosper, but the generous terms under which the land was offered resulted in many purchases in London, Bristol, and even in Dutch and German cities.

On April 23, 1682, Captain Thomas Holme set sail from London on the Amity, having been commissioned by William Penn as surveyor general of Pennsylvania. Holme arrived at the site of Philadelphia late in June and immediately began laying out the city on the elevated ground between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers.

Under Penn’s rule, there would be a governor, a provincial council, and an assembly. The council comprised 72 freemen to serve for three years, with one-third being replaced each year. The governor was to have three votes in the council but no power of veto. The council alone had the right to originate bills. The governor and council together constituted the executive power, and by division into committees were to manage the affairs of the Province. The assembly was to consist, for the first year, of all the freemen of the Province and, after that, of 200 people to be elected each year.

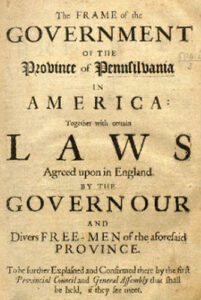

Pennsylvania Frame of Government

On April 25, 1682, Penn, still in England, completed his famous “Frame of Government.” He called the document The Frame of Government of the Province of Pennsylvania in America, together with specific laws agreed upon in England by the Governor and Freemen of the Province, to be further explained by the First Provincial Council. In the constitution, he declared the divine right of government was twofold: to “terrify evildoers and to cherish those that do well.”

Among his many schemes for developing the city and Province, Penn set a great store on the Free Society of Traders, a land and commercial company chartered in London. Its president was Nicholas Moore, a London doctor who came to Philadelphia shortly after Penn’s arrival and later became speaker of the assembly and chief justice.

To attract wealthy individuals, Penn offered parcels of 5,000 acres for £100, with 50 acres additional for every indentured servant brought to Pennsylvania. An opportunity was given to entire families to purchase tracts of 500 acres, to be paid for in annual installments over several years.

On May 5, 1682, Penn’s Code of Laws was passed in England to be altered or amended in Pennsylvania. In this document, 40 statements were proclaimed, which became the fundamental law of the Province. Among the provisions were that elections should be voluntary; taxes were to be levied for purposes specified; complaints were to be received upon oath or affirmation; trials were to be by a jury of 12 men, peers of good character, and the neighborhood. If the crime carried the death penalty, the sheriff was to summon a grand inquest of 24 men; fees were to be moderate; each county was to have a prison that would also serve as a workhouse for felons, vagrants, and idle people; and public officers and legislators were to take an oath to speak the truth and profess belief in Jesus Christ.

William Penn arrived in Pennsylvania on the Welcome in 1682.

Finally, Penn was ready to turn his back upon England and start a new chapter in the wilderness of America. Winding up the last of his affairs, he boarded the Welcome at Deal on September 1, 1682, and set sail for Pennsylvania with Captain Robert Greenway and 100 passengers. Among them was a passenger bearing deadly smallpox germs. Nearly half the crew and passengers were down with the illness within a few weeks, and the bodies of 30 victims were buried at sea before land was sighted. The Welcome, pushing her slender bow through the North Atlantic seas for eight weeks, also battled gales.

On the morning of October 27, Penn landed in New Castle, Delaware, where he was greeted by his cousin, Captain William Markham, who was in naval uniform, and by a gathering of Dutch, Welsh, and English settlers. Tall, handsome, and still slender, Penn made an impressive appearance as he formally took possession of the Delaware River territory.

Impatient to see his Province of Pennsylvania, he proceeded that afternoon to Upland — settled by the Swedes about 40 years before — and landed at the mouth of Chester Creek. Here, he was entertained over the weekend at Essex House, home of Robert Wade, a Friend Penn had known in London. At that time, Upland was the most populous town in the new Province of Pennsylvania. Penn renamed the settlement after the English city of Chester.

William Penn arrived in Pennsylvania by Leon Jean Gerome Ferris in 1932.

Building construction began with vigor in the spring. For himself, Penn had ordered a house commanding a view of the Delaware River, but it was not until March 10, 1683, that he took up residence. By this time, the Province had been divided into Philadelphia, Chester, and Bucks Counties, and the Great Law and the Frame of Government had been adopted by the assembly, which had its first session in Chester on December 4, 1682. Philadelphia was a crude, rough frontier settlement in the first years after its founding. Some early settlers lived in caves on the Delaware Riverbank before moving into log houses.

In 1683, several settlers made their way into the wilderness. More than 20 vessels loaded with immigrants arrived in Philadelphia before the end of the year. Penn’s plan was moving toward the success he had prayed and labored for.

On June 10, 1683, the ship America, with Captain Joseph Wasey in command, sailed from Deal, England, with a scholarly gentleman aboard — a man who was to play an essential role in the history of Philadelphia. He was Francis Daniel Pastorius, founder of Germantown and forerunner of a great wave of immigration. Pastorius and his party of nine arrived in Philadelphia on August 20, six weeks earlier than the main body of the first Germantown colonists. These, coming from Crefeld, arrived on the Concord, commanded by Captain William Jefferies, on October 6, 1683. They were not of German origin, as is commonly supposed, but were Dutch Quaker descendants of Mennonites who had taken up residence in the Rhine country after being driven from the Netherlands. There were 80 people, including Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists, Anabaptists, Episcopalians, and one Quaker.

“The caves of that time were only holes dug in the ground, covered with earth, five or six feet deep, 10 or 12 feet wide, and about 20 feet long. Neither the sides nor the floors have been planked. Herein, we lived more contentedly than many nowadays in their painted and wainscoted palaces, as I, without the least hyperbole, may call them compared to the aforesaid subterraneous catacombs or dens.”

— Daniel Pastorius, founder of Germantown

Market Square, Germantown, Pennsylvania by William Britton, 1820.

Six days after his arrival, Pastorius obtained from Penn a warrant for approximately 6,000 acres on the east side of the Schuylkill River. The tract was divided between the German Company and the Crefelders. German Town settlement was laid out with a main street 60 feet wide and cross streets 40 feet wide. For each house, a lot of three acres was provided. Pastorius doubled the acreage for his dwelling. The small settlement grew, and in 1685, Pastorius reported that 12 families, numbering 41 people, lived in the colony.

Sometime during the first week in November 1683, Penn and a party of friends rowed upriver to the tongue of land formed by the converging Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers, where the town of Philadelphia was being laid out. They continued past the Schuylkill River’s mouth, proceeding up the Delaware River to where Dock Creek led into a large green clearing on the river’s west bank. The place was called Coaquannock by the Indians because of its tall pines. Small Swedish settlements such as Wicaco and Tacony had been established nearby.

Swedes owned some of the lands Penn desired, and still more belonged to the Indians, particularly the Unami of the Lenni-Lenape nation. Since Penn’s agents had already acquired considerable acreage from them, the Delaware River clearing had become a real estate development. Under the supervision of Captain Thomas Holme, the surveyor general that Penn had sent to America with the advance guard of settlers, trees were being felled and cut into logs, plots were being leveled, streets graded, houses built, and Penn’s plan was laying out the city.

“Colonies are the seeds of the Nation.”

— William Penn

Duke of York.

During the next few weeks, Penn was busy. He visited New York to pay his respects to representatives of the Duke of York, made frequent trips to Philadelphia to observe the growth of his “Greene country towne,” and, in Chester, worked on the plan of government for his Province. Meanwhile, he kept in contact with his agents in London, circularizing Europe with pamphlets — in English, German, and other languages — which pictured the beauties of America and outlined the advantages to be gained by coming to the new land.

As a result of this promotion campaign, immigrants poured into Pennsylvania during the ensuing years. Among them were so many Germans that James Logan, Penn’s secretary, feared it would become a German colony. One of the features attracting Europeans was Penn’s Great Law and Frame of Government, which made provisions for free education, promotion of the arts and sciences, religious toleration, freely elected representatives, and trial by jury in open court.

However, many of the earliest settlers in Philadelphia found existence far from comfortable. Significant numbers of them had to live for a time in dug-outs gouged from the Delaware River’s banks. There was no let-up in construction; during the first year after Penn’s arrival, more than 100 dwellings of brick, logs, and wide clapboards were constructed, some with balconies and porches. Brick houses were few initially, but the number increased as soon as bricks could be manufactured locally.

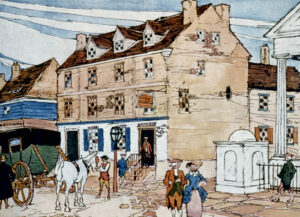

The Blue Anchor Inn in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was built in 1682.

Within a year of Penn’s landing, the growing town boasted 600 houses. The Blue Anchor Inn, built in 1682 on the bank at the mouth of Dock Creek, serving as Philadelphia’s tavern, trade headquarters, and community center, was no longer the most substantial building in town. Some of the homes were becoming almost pretentious, wharves were growing in size and number along the Delaware River, and surrounding farms by the hundreds were being cleared and tilled. Penn proudly wrote to his friends in England: “I have led the greatest colony into America that ever man did upon a private credit. I will show a province in seven years equal to her neighbors’ 40 years’ planting.”

Robert Turner erected the city’s first brick house at the corner of Front and Arch Streets in 1684. The same year, Quakers erected the Bank Meeting House on Front Street, and William Penn’s Council mandated public steps at every block to ensure access to the Delaware River. That year, William Penn sailed for Europe, where he would remain for 15 years. During this protracted trip, he experienced many essential changes in his private and public life. Becoming involved in royal intrigue, he was arrested on several occasions and had to submit to humiliating investigations.

Samuel Carpenter, a wealthy West India merchant, constructed the town’s first wharf at the rear of his lot along the Delaware River at Walnut Street in 1685. In exchange for the right to build his wharf and charge for its use, Penn’s Council required Carpenter to construct steps from the water’s edge to the bank’s top and a 30-foot cartway along the bank.

The first prison and stocks, a primitive log building, opened on the eastern side of 2nd Street at Market Street in 1687. The city quickly outgrew the facility and rented nearby space for detentions.

Germantown was incorporated as a borough in 1689. Francis Pastorius was the borough’s first bailiff, and two Op de Graeff family members and Jacob Fellner were appointed magistrates. Together with eight yeomen, these men formed a general court that sat once a month, created laws, and imposed taxes.

From the city’s founding, the Old City District, at the heart of Philadelphia, was the center of political, economic, and cultural life in the colonies and the nation. Owing to its significance, many of the period’s most influential people lived and worked in the District.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Port.

Penn planned his city on the Delaware River to serve as a port and place for government. Hoping that Philadelphia would become more like an English rural town instead of a city, Penn laid out roads on a grid plan to keep houses and businesses spread far apart with areas for gardens and orchards. However, the city’s inhabitants did not follow Penn’s plans and instead crowded the present-day Port of Philadelphia on the Delaware River, subdividing and reselling their lots.

Penn was ousted from the proprietorship of Pennsylvania on March 10, 1692, and it would not be until August 9, 1694, that the Province was restored to him.

In 1693, a more substantial prison was constructed near the courthouse to replace the former log prison. Butchers’ stalls operated beneath the courthouse as part of High Street Market, Philadelphia’s first, which opened at 2nd Street in 1693. Twice a week, merchants sold their wares at stalls running down Market Street’s center.

Old City’s Quaker meeting moved from the Greater Meeting House at 2nd and Market Streets to a plot at 330 Arch Street that William Penn had set aside in 1693 as a burial ground. There, the Quakers erected the Arch Street Meeting House in two phases, from 1803 to 1805 and 1810 to 1811. The largest Quaker meeting house in the world and the headquarters of the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of the Society of Friends initially housed separate meeting rooms for men and women.

On February 23, 1694, Penn’s wife died and was buried beside four of their children. A fifth child died in 1696.

The city’s first ferry business, Daniel Cooper’s Ferry, opened in 1695 on a wharf at the foot of Arch Street and operated between Philadelphia and New Jersey. During the ensuing 250 years, numerous other ferries plied the waters between Philadelphia and New Jersey, transporting passengers, vehicles, and cargo.

In February 1696, Penn married Hannah Callowhill, daughter of a Bristol linen dealer, a woman of character and determination. In his second union, there were six children. He was 64 when his youngest child was born.

Construction began to replace the Quaker’s Bank Meeting House in 1696. Its replacement was the Great Meeting House at the southwest corner of S. 2nd and Market Streets. The 50 feet square building was built for approximately $1,000. It was called the Great Meeting House, for it was the largest meeting place for Friends for half a century.

By 1698, Philadelphians had cut nine alleyways from N. Front to N. 2nd Streets and erected several rows of two-story workers’ cottages. Without sanitation systems, unhealthy conditions abounded in the densely packed riverfront neighborhood, and pigs and goats ran freely through the streets.

William Penn returned to Philadelphia in 1699.

Eager to return to Pennsylvania, William Penn set about winding up his affairs in England. He made a preaching tour through Ireland, stayed at the Shannigarry estate for a while, and then sailed for America with his wife and daughter, Letitia. They took passage on the Canterbury. Which left Cowes Road, Isle of Wight, on September 9, 1699. The passage was long and tedious; winter had set in when they arrived in Philadelphia. It was not a pleasant homecoming, though Penn’s heart must have been thrilled at the sight of the busy waterfront, the long rows of red-brick houses, and the tidy little farms surrounding his compact town.

At Chester, he found the yellow fever epidemic, and in Philadelphia, he found a difficult body of men with whom to deal at the assembly. Two bills presented by Penn — one to prohibit the sale of rum to Indians, the other to provide for the decent marriage of African Americans — were rejected with humiliating bluntness. The council was even more hostile. Penn soon realized he was proprietor in name only. To the Indians, he was still the great sachem, the King of Men, but to the settlers in Philadelphia and the growing Province, he was an over-scrupulous old man obstructing progress.

The founder lived in the Slate Roof House, a grand residence at Second Street and Sansom Street, for a while. He had plenty of time to spend with his family and still attend to state affairs, though delegations and official visitors were frequent. His wife, however, did not enjoy life as a governor’s wife and hostess and preferred the simple life she led in England. Later, they moved to his Pennsbury estate along the Delaware River River in Bucks County. Here, Penn lived in more or less political seclusion, maintaining a six-oared barge on the river, keeping purebred horses, a well-stocked pantry, and a cellar. However, his restless nature led him to wander throughout the Province on visits to Indian villages and outlying settlements.

In 1700, a local pastor, Andreas Rudman, stated: “If anyone were to see Philadelphia who had not been there, he would be astonished beyond measure that it was founded less than 20 years ago… All of the houses are built of brick, three or four hundred of them, and in every house a shop, so that whatever one wants at any time he can have, for money.”

By then, Philadelphia had burgeoned into the third-largest port on the Atlantic Ocean after Boston, Massachusetts, and New Amsterdam, New York, with a population of 2,000 to 2,500.

Shipbuilding in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

18th Century

During the 18th century, shipbuilding, import-export businesses, and primary maritime activities flourished along the Delaware River. Typical Philadelphians lived on an unpaved street near the banks of the Delaware River and worked in a shop at home or at a nearby wharf or warehouse. The houses, of which there were several hundred by 1701, typically included an office and a warehouse or store on the first floor and living quarters above. Even wealthy families often used portions of their residences as workplaces.

In 1701, the English Parliament attempted to bring Pennsylvania under direct royal control. Though keenly desirous that Penn should hurry to England and thwart the bill, the assembly appropriated money only after repeated delays. By that time, Penn’s finances were in a deplorable condition, and even the large acreage of his Pennsbury estate had dwindled. Word of the Founder’s imminent departure was treated with indifference by Philadelphians, but Indians, by the score, came into the little city to say farewell to him. Penn appointed Colonel Andrew Hamilton, the former governor of East and West Jersey, as deputy governor of Pennsylvania and James Logan as colonel secretary. Before Penn left Philadelphia for the final time, he issued the Charter of 1701, establishing it as a city. Then, in October 1701, he set sail for Portsmouth, England, with his wife and family.

After 1701, with Penn having granted religious and political freedoms to all citizens of Pennsylvania with his Charter of Privileges, many oppressed individuals seeking to worship freely immigrated to Philadelphia. Immigrants representing many religious groups settled in Old City Districts, one of the city’s densest and most diverse neighborhoods.

Penn intended to remain abroad only long enough to straighten out the affairs of the Province. However, forces that had no connection with the state’s problems kept him from ever returning to America. By 1705, he had obtained unquestioned autonomy for Pennsylvania through a grant from Queen Anne, despite the Crown’s growing tendency to check proprietary power in the New World. However, his private affairs became so involved in claims and counterclaims that he eventually became a voluntary inmate of a debtor’s prison.

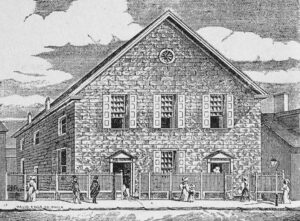

The first courthouse in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The first public courthouse in the city, a 2½ story brick building with a steeply-pitched gable roof and cupola, was built about 1708 in the middle of Market Street at 2nd Street. This court building was the meeting place for the Provincial Assembly and the city government. A more substantial prison was constructed near the courthouse to replace the former log prison.

In the autumn of 1708, William Penn lived quietly with his wife and some of their children in Brentford, England. He was then in his middle sixties, significantly overweight, and constantly ailing. His health declined rapidly, and his mind became affected. Despite this mental and physical decay, a stubborn spark of that energy persisted, driving him to wild frontiers in middle age. Now, in the twilight of life, he guided his tottering footsteps in restless walks through the garden.

In the spring of 1712, Penn suffered a paralytic stroke while visiting London. He had a second stroke in Bristol that autumn and a third at Ruscombe in January 1713. In 1715, he suffered several minor strokes, and his memory was a complete blank for long periods of time after that. He died July 30, 1718, at 74, and was buried on August 5 at Jordan’s Cemetery near Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire.

The following two decades saw the waning of Penn’s empire in Pennsylvania and the gradual decline of Quaker dominance in Philadelphia’s political affairs. These years also witnessed civic improvement, expansion of foreign industry, and periodic epidemics of malignant diseases. While Philadelphia was paving streets, organizing fire companies, and developing industries, pioneers on the remote frontiers struggled with the stubborn wilderness.

A new stone prison with a high perimeter wall was erected in 1722 at the southwest corner of 3rd and High Streets. It was used until the American Revolution when a new facility was built.

Benjamin Franklin arrived in Philadelphia in 1723 and quickly asserted his influence. He built his residence, Franklin Court, to the south of his properties at 314-322 Market Street. The noteworthy buildings at 314-322 Market Street (1786-1805), along with the ghost of Franklin’s house, now form part of Independence National Historical Park.

Benjamin Franklin Postmaster.

Franklin and others founded the colonies’ first firefighting organization, the Union Fire Company of Philadelphia, in the Old City District on December 7, 1736. By the middle of the century, six fire companies served Philadelphians. The following year, he was appointed Philadelphia’s postmaster.

By the 1740s, Philadelphia boasted a population of 10,000, occupying 1,500 dwellings, second only to Boston, Massachusetts.

In 1741, Ben Franklin opened his first printing shop with a fellow printer on Market Street near 2nd Street.

In 1745, a New Market providing additional stalls opened outside the District on S. 2nd Street between Pine and South Cedar Streets.

Though initially poor, Philadelphia became an important trading center with tolerable living conditions by the 1750s. Benjamin Franklin helped improve city services and founded new ones, including a fire company, library, and hospital, among the nation’s first. By then, Philadelphia surpassed Boston as British America’s largest city and busiest port and the second-largest city in the British Empire after London.

Street lighting and paid night watchmen were authorized by the Assembly in 1751 and funded with a tax, which helped reduce nighttime crime. The following year, Benjamin Franklin was instrumental in creating the Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire, the colonies’ first fire insurance company.

In 1754, there were at least 12 shipbuilding businesses between Washington Avenue and Vine Street.

The City assumed responsibility for paving and cleaning streets with tax funds and lotteries in 1762.

By 1765, Philadelphia had surpassed Boston in population, with 25,000 people occupying 5,000 residences. That year, Philadelphia was considered the fourth largest city in the British Empire, surpassed only by London, Edinburgh, and Dublin.

The Revolutionary Period

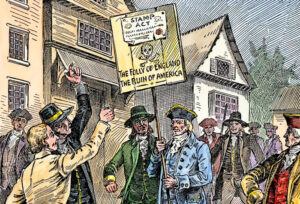

Stamp Act.

On March 18, 1766, Parliament repealed the hated Stamp Act. On May 20, the brig Minerva, commanded by Captain Wise, brought the joyous tidings to Philadelphia. Immediately, there was public rejoicing, and huge bonfires blazed throughout the night as the town celebrated the grand event. The following day, toasts of allegiance were drunk to the King at a public dinner held in the State House.

However, the general feeling of amity toward the mother country turned to indignation when it became apparent that the Crown did not intend to abandon the rich revenues from the Colonies. The repeal of the Stamp Act had strings attached to it in the accompanying Declaratory Act, reiterating the right of Parliament to tax the Colonies in any way it deemed fit. The Townshend Acts, levying heavy duties on paper, glass, tea, and lead, were passed by Parliament on June 29, 1767.

The colonists’ reaction to these new taxes resulted in a boycott of all British goods. The arguments of John Dickinson’s famous Farmer’s Letters, a series of articles that appeared on December 2, 1767, and the last on February 15, 1768, in William Goddard’s Pennsylvania Chronicle, helped to stiffen the colonists’ determination to resist taxation without representation. Philadelphia, fittingly, assumed the lead in the resistance movement, which grew in intensity during the following six years.

By the 1770s, the crowding of the land exceeded the sanitary capabilities of the town. The streets and alleys reeked of garbage, manure, and human waste, and some private and public wells became dangerously polluted. Every few years, an epidemic swept through the town.

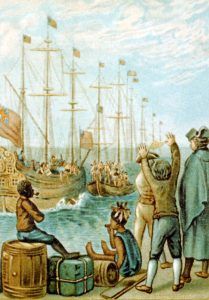

Boston Tea Party by D. Berger.

The situation worsened when Goddard’s Chronicle, on September 27, 1773, reported that a shipload of British tea was on the way to Philadelphia. More amendments had modified the acts of 1767 to tax tea only, with importation becoming the main issue. By permitting the East India Company to ship untaxed tea to America, the British government was forcing the issue that a three-penny Colonial tax would be imposed upon the commodity. The Colonies retaliated by refusing to permit the landing of the tea. In Boston, citizens disguised as Indians boarded a newly arrived tea ship one night and dumped the cargo into the harbor. In Philadelphia, the resistance, though less destructive, was no less determined.

News of the Boston Tea Party reached Philadelphia on December 24. The following day, word was received that the Polly, a ship from London carrying a consignment of tea from the East India Company to Philadelphia, was lying off Chester. Fanning the flames of resentment, a committee of action was organized, and threats were openly made that any pilot who dared to bring a British tea ship to Philadelphia would be hanged.

In the meantime, the Polly continued her course up the Delaware River to Gloucester, New Jersey, where Captain Ayres was told he would not be permitted to land his cargo. After conferring with the committee, he agreed to leave the ship and go to Philadelphia. On the next day, December 27, a large public meeting was held in the State House, and it was unanimously resolved that the tea should be rejected and returned to England and that Ayres should be allowed one day to provision his ship for the return voyage. After making a formal protest, Ayres agreed to comply with the committee’s demands, and on December 28, he set sail for London with the cargo of rejected tea.

This incident and the Tea Party in Boston constituted acts of defiance that the London government could no longer ignore. Consequently, Parliament enacted a bill to close the port of Boston to all shipping, which was put into effect in June 1774 with the arrival of royal troops and British men-of-war to the New England port. Paul Revere had reached Philadelphia in May, bringing a letter concerning the King’s threat to close the Port of Boston and earnest requests from the Boston leaders for support.

City Tavern in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In Philadelphia, at a meeting of leading citizens in the City Tavern, a resolution favoring the support of Boston was adopted. Letters were dispatched to the Southern Colonies to enlist their support, and the Governor was asked to convene the assembly. On June 1, a popular demonstration against the Boston Port Bill was staged.

On June 18, 1774, at the State House, a meeting of the general congress was called for all the colonies to hold a state conference at Carpenters’ Hall on July 15. Attended by 77 delegates from 11 counties, the meeting asserted the colonies‘ right to resist Parliament’s unjust measures and requested the Provincial Assembly appoint delegates to the forthcoming Continental Congress.

Philadelphia hosted the First Continental Congress between September and October 26, 1774, in Carpenters’ Hall. The opening session on September 4, 1774, had 44 delegates assembled, and within a few weeks, the number increased to 52, representing eleven of the 13 Colonies. Peyton Randolph of Virginia was chosen president, and Charles Thomson was secretary. Other prominent delegates were John Adams, Richard Henry Lee, George Washington, John Jay, Patrick Henry, and Samuel Adams.

Congress’s deliberations were held behind closed doors and continued for six weeks. When it adjourned on October 26, resolutions of the independence movement had been adopted. The most important were the Declaration of Rights and the Articles of Association, the latter of which is regarded as the forerunner of the Articles of Confederation.

By the opening months of 1775, tensions between England and the Colonies had increased. The Articles of Association adopted by the Continental Congress especially aroused the ire of King George, who saw them as an overt act of treason against the Crown.

American Revolution

Continental Army by Henry Ogden

The long-brewing storm broke on April 19, 1775, when the King’s troops clashed with the Minute Men at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. The War for Independence had begun! The news of the bloodshed spread along the eastern seaboard, and thousands of volunteers converged in Cambridge, Massachusetts. These were the beginnings of the Continental Army.

Continental officials were worried that the British would immediately target the city while General George Washington was still consolidating his army. However, the dreaded invasion would not occur for the next few months.

In 1776, British General William Howe captured New York City and, in the following year, set his sights on Philadelphia’s capital. Rather than march overland to assault the city, Howe sailed his army around Maryland and up the Chesapeake Bay. He landed his army in Maryland and began marching south towards Philadelphia.

He struck out at Philadelphia in August 1777 from his base in New Jersey, hoping to draw out General George Washington and defeat him on the open field. Washington and his army tried to block Howe at Brandywine Creek, just ten miles from Philadelphia, on September 11, 1777. Though the Americans fought bravely all day, Washington was flanked and defeated, opening the door for the British Army to march into the American capital.

Though Howe inflicted heavy casualties on the American troops, he failed to destroy Washington’s Army, which relocated to Lancaster along with the Continental Congress. Howe then proceeded into Philadelphia unopposed.

On October 4, 1777, Washington attempted to retake Philadelphia at the Battle of Germantown in October 1777. Just outside of Philadelphia, the battle appeared to go in the Americans’ favor, but soon, the tide shifted, and Washington was driven back.

The British occupied Philadelphia in 1777.

From September 1777 to June 1778, the British occupied the American capital for nearly a year. Loyalist civilians welcomed the British, while Patriot civilians endured the occupation. Despite losing their capital city, George Washington and the Continental Army continued resisting while the Continental Congress fled to York, Pennsylvania. Unable to dislodge the British, Washington’s army settled into winter quarters at Valley Forge, where thousands of soldiers died of disease. Despite the conditions, the Continental Army came out of the ordeal stronger and more disciplined than ever, ready to take on the British army.

The occupation of Philadelphia was difficult for those residents that remained. Though looting was frequent, though against Howe’s wishes, even after discovering that Continental troops took most of the useful military supplies. Howe took up residence in the Masters-Penn House, which later became the President’s House under Washington and Adams when Philadelphia was the capital. Although he had taken the city, Howe’s forces failed to take control of the surrounding area, as many of his incursions were repulsed by skirmishes with Continental troops. During this time, Howe was unable or unwilling to support his colleague and rival, General John Burgoyne, in upstate New York. Howe’s petty squabbles ultimately led to Burgoyne’s disastrous defeat at Saratoga, New York, emboldening the Continental Army and securing French support for American independence.

When news reached Philadelphia that France had joined America’s side, General Henry Clinton, now the British commander, left Philadelphia in June 1778. While marching overland from Philadelphia to New York City, Washington’s army attacked the British in New Jersey and fought them to a draw at the Battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778.

Peace in Philadelphia

Benedict Arnold by John Trumbull, 1894.

Congress returned to the city on June 25, 1778, and convened in Independence Hall. Benedict Arnold, who later became infamous for his treacherous conduct at West Point, was appointed military commander of the city by General Washington. The following months were marked by extreme bitterness against the Tories, treason trials, lawsuits, and heated controversies.

In 1780, Robert Morris and others founded the Bank of Pennsylvania.

French support of the American cause changed the tide of war and led to the British’s final capitulation at Yorktown, Virginia, on October 19, 1781.

The Bank of North America, the first to be chartered by the Congress, was opened on January 17, 1782, on Chestnut Street near Third.

On April 16, 1783, the conclusion of peace and Britain’s acknowledgment of American independence were officially proclaimed in Philadelphia amid great public rejoicing.

With the return of peace, industry and commerce soon revived. Despite high prices, money became more abundant, and the general prosperity of the city increased. By the middle of June 1783, 200 vessels had sailed up the Delaware River.

Two former slaves, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, received licenses to preach from the Methodist Church at St. George’s Church in 1784. They began holding early-morning services for African Americans.

In 1786, Dr. Benjamin Rush opened the first medical dispensary in America in the city. The following year, the Pennsylvania Society for the Encouragement of Manufactures and Useful Arts, the archetype of present-day chambers of commerce, was established. Mail and stagecoach service to Reading and Pittsburgh was inaugurated.

First African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The growing popularity of church services for blacks led to a confrontation over seating in 1787. Shortly after, Allen and Jones withdrew from St. George’s and founded the Free African Society to aid the sick and the distressed. Richard Allen later founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church, now the largest African American church in the nation.

The U.S. Constitution was ratified in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787.

Philadelphia’s population was 53,000 in 1790. At that time, Philadelphia was the nation’s financial and cultural center until New York City eclipsed it in total population that year.

The President’s House on Market Street served as the presidential mansion for the nation’s first two presidents, George Washington and John Adams, from 1790 to 1800, before the completion of the White House and the development of Washington, D.C., as the nation’s new capital.

In 1793, the largest yellow fever epidemic in U.S. history killed approximately 4,000 to 5,000 people in Philadelphia, or about ten% of the city’s population.

Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton commissioned the 1797 First Bank of the United States when the nation adopted a single currency. Photo by Carol Highsmith.

In 1795, Samuel Blodgett Jr. designed a building for the First Bank of the United States, the second significant institution to settle in the banking district. The bank’s grand Palladian building still stands adjacent to the District on S. 3rd Street.

Old City Catholics founded St. Augustine’s Church in 1796.

In 1798, public landings along the waterfront were at the intersections of Water Street and the major east-west streets. There were also ferries at Mulberry and High Streets. Privately owned piers settled in the areas between the public landings. Many related industries sprouted to service the maritime businesses, including blacksmiths, foundries, ropemakers, sailmakers and repairers, bakers, butchers, and cold storage companies. Taverns, shipyards, and warehouses also flourished. Adjacent to their stores and warehouses, wealthy merchants built extravagant townhouses.

The state capital was moved from Philadelphia to Lancaster in 1799, then ultimately to Harrisburg in 1812.

City services were greatly improved during the later 18th century, and a new prison was erected outside the district at the southeast corner of S. 6th and Walnut Streets. At the same time, the city began constructing a municipal water system to pump clean water from the Schuylkill River to a pumping station and water tower at Centre Square and then to homes and businesses.

The capital of the United States was moved to Washington, D.C., in 1800 upon completion of the White House and U.S. Capitol buildings. That year, Philadelphia, still the country’s largest city, had grown to 68,000.

19th Century

Freshwater first flowed through the municipal water system’s pipes in 1801. That year, the Catholic parish St. Augustine erected a church building on N. 4th Street, near Vine, the first permanent establishment of the Augustinian Order in the United States. In 1811, St. Augustine’s Academy, affiliated with St. Augustine’s Church, provided a parochial education.

The Academy of Natural Sciences was established in 1812.

The Fairmount Water Works complex was initially constructed between 1812 and 1815 on the east bank of the Schuylkill River. Photo by Carol Highsmith.

Between 1812 and 1815, engineer Frederick Graff greatly enhanced the water system by establishing the Fairmount Water Works. During the first decades of the century, indoor plumbing was first installed in better housing. In addition, water from public hydrant pumps was readily available in the built-up sections of the city. However, bathing was not widely practiced, with only five public baths within the city limits.

In 1816, the city’s free Black community founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent Black denomination in the country and the first Black Episcopal Church. The free Black community also established many schools for its children with the help of Quakers. Large-scale construction projects for new roads, canals, and railroads made Philadelphia the first major industrial city in the United States.

A system of public schools was established for the poor in Philadelphia in 1818.

Between 1818 and 1824, the federal government constructed a building for the Second Bank of the United States, the most important institution on Bank Row. Designed by noted architect William Strickland, the Second Bank of the United States building, which faces the District, popularized the Greek Revival style.

The Christ Church ran a large hospital at 306-308 Cherry Street from 1819 to 1861, when the institution moved to West Philadelphia.

Although Philadelphia had always been an American manufacturing center, it was established as the leading industrial city in the country by the 1820s. The discovery of coal, a cheap power source for steam engines and furnaces, in central Pennsylvania during the 1820s hastened industrial development. Philadelphia quickly became a hub for manufacturing steam engines, which were soon employed in numerous industries, including carpet weaving, brewing, milling, and iron smelting.

In 1822, a magnificent, domed market terminus with a clock, bell for openings and closings, and an office for the market clerk was erected at Front and Market Streets. The same year, the Washington Grays of Philadelphia, also known as the Volunteer Corps of Light Infantry, was formed. It became the Pennsylvania National Guard in 1879.

The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

The Franklin Institute was established in 1824. These societies developed and financed new industries that attracted skilled and knowledgeable immigrants from Europe.

In 1830, a bathhouse, perhaps the first in Old City, was established at Little Boy’s Court and Arch Street, between N. 2nd and N. 3rd Streets.

In the early 1830s, William Strickland designed the Greek Revival Merchants’ Exchange at S. 3rd and Walnut Streets. A center for the neighborhood’s commercial activity, the Exchange served as a stock exchange, site for auctions, real estate and business dealings, meeting place, and outlet for business and shipping news.

During the 1830s, the first railroad lines were introduced into Philadelphia. Older industrial areas such as Manayunk, which had relied on water power, expanded with the introduction of steam engines. Other areas, especially those along the new rail lines, developed into burgeoning industrial zones. North of Market Street in Old City, manufacturing likewise expanded but remained relatively small in scale. One exception was the sugar refinery on Church Street between N. 2nd and N. 3rd Streets. Established in 1792, the Steam Sugar Refinery operated by Joseph S. Lovering & Company at 225 Church Street grew into an enormous industrial complex. A section of the original 1792 building and several significant mid-19th-century additions still stand along Church Street.

The passage of the Free School Law in 1834 established a state-funded, tax-based school system for all children in Pennsylvania. The Northeastern School, one of the first notable public schools in the Old City neighborhood, was located at 120 New Street, on the south side between Front and N. 2nd Streets.

Immigrants from Ireland and Germany settled in Philadelphia and the surrounding districts. These immigrants were primarily responsible for the first general strike in North America in 1835, in which workers in the city won the ten-hour workday.

Merchant’s Hotel in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, by John Rubens, about 1840.

In 1837, William Strickland designed a Greek Revival-style building for the Mechanics’ Bank. Still standing at 22 S. 3rd Street, the much-abused and little-appreciated Mechanic’s Bank building is one of the most significant examples of the style in the District. The following year, Francis M. Drexel established the Drexel & Co. investment banking house, one of the 19th century’s most powerful financial institutions, at 34 S. 3rd Street. The Merchants’ Hotel, also known as the Washington Hotel, was also built in 1837 at 40-50 N. 4th Street. Designed by prominent architect William Strickland and known for its luxurious furnishings, the hotel was destroyed by fire in 1966.

In 1840, a visiting British military officer remarked that “hundreds of omnibuses are constantly in motion in every direction” in downtown Philadelphia. Although most Philadelphians continued to travel by foot, the omnibus marked the beginning of a transportation revolution that would include the streetcar, commuter railroad, trolley, and automobile and would, over several decades, lead to the simultaneous demise of the walking city and creation of the suburbs. This transportation revolution also led to the homogenization of the Old City. What had once been a diverse aggregation of residential, commercial, industrial, and institutional sites developed into a more homogeneous neighborhood with a wholesale and industrial district centered on Front Street north of Market Street and a financial district along Chestnut Street. Despite this trend, Old City continued to be more diverse than most neighborhoods.

In 1841, the City purchased the rights of the Philadelphia Gas Company, which had never exercised its license. It began to deliver gas throughout the developed sections of the city, including the District.

The city was a destination for thousands of Irish immigrants fleeing the Great Famine in the 1840s; housing was developed south of South Street and later occupied by succeeding immigrants. They established a network of Catholic churches and schools and dominated the Catholic clergy for decades.

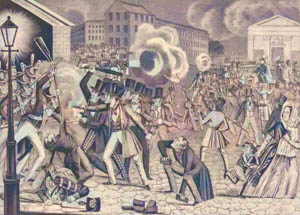

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania riots, 1844 by H. Bucholzer.

Anti-Catholic, anti-Irish forces led by the Know Nothing Party burned St. Augustine’s Church and school, along with other Catholic churches and buildings in Philadelphia during the nativist riots of 1844, the city’s worst mob violence.

Within four years, parishioners had replaced the destroyed church with a restrained, formal, Palladian-inspired building. Renowned church architect Edwin Durang added the brick and wood steeple in 1867. It toppled during a storm in 1992 and was reconstructed a few years later.

In 1844, the 105-room American House hotel opened on Chestnut Street across from the State House, west of the District. The United States Hotel opened shortly after, facing the Bank of the United States on Chestnut Street.

In 1845, sugar baron Joseph Lovering was one of Old City’s two millionaires. The other, Francis M. Drexel, operated a financial house at 34 S. 3rd Street.

The year 1848 was marked by Abraham Lincoln’s first visit to the city and the Whig National Convention, at which Zachary Taylor was nominated for the presidency.

In 1849, the Philadelphia County Medical Society was founded. The following year, Philadelphia’s police force was established, with the appointment of two assistants to the constable. In 1849 and 1850, the 133-foot tall Jayne Building, one of the country’s first “skyscrapers,” was erected.

Fire in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, by James Fuller Queen.

Despite Philadelphia’s tradition of brick construction and the proliferation of fire companies, fire plagued the Old City district. One of the city’s worst fires began in a store on N. Water Street below Vine Street on July 9, 1850. Before it was extinguished, it had killed 28, injured 100, and destroyed 367 buildings on 18 acres. Fire insurance companies followed in the wake of the establishment of the fire companies. At that time, the city and suburban population was more than 360,000. But the city proper, as delimited by the charter of 1789, had a population of only 121,000. Thus, while the city was steadily growing, its governmental structure was lagging behind.

In 1851, the Spring Garden Institute and the Shakespeare Society were founded. The same year, the St. Charles Hotel, which still stands at 60-66 N. 3rd Street, was built. This Italianate hotel with an early important cast-iron facade boasted an innovative plan: a bar and reading room on the first floor, a parlor for women on the second floor, and more than 50 guest rooms on the top three floors.

By 1853, 113 miles of gas pipe supplied Philadelphia and the surrounding townships. Most Philadelphians embraced the new technology. The introduction of street and interior gas lamps revolutionized life in the city. The powerful new lighting, which replaced oil lamps and candles, shifted many activities from day to night and even created the possibility of nightlife.

With the growth of the city and its adjoining districts, each of which had separate municipal powers, a situation arose that necessitated consolidation. The districts and boroughs of Southwark, Spring Garden, Moyamensing, Northern Liberties, Richmond, Kensington, West Philadelphia, Belmont, Germantown, Roxborough, Frankford, Manayunk, Bridesburg, and Kingsessing were independent and conflicting municipalities, which gave rise to many abuses and costly inefficiencies that hampered development. The Act of Consolidation of 1854 extended the city limits from the two square miles of Center City to the roughly 134 square miles of Philadelphia County. At that time, the new City of Philadelphia took over all the property and debts of the incorporated districts.

With consolidation, the city entered a new era of progress. In 1856, the first Republican National Convention was held at Musical Fund Hall when John C. Fremont was nominated for the Presidency. The Academy of Music was opened, Mayor Richard Vaux organized the fire and police systems, and the Schuylkill Navy was established in 1857. That year, however, the city’s developments suffered a temporary setback because of a severe economic depression. The first symptoms appeared when the Bank of Pennsylvania closed its doors in September 1857. Within a few hours, several other banks suspended coin payments. Excitement ran high, and police were called out to protect the banks from depositors clamoring for their money.

The financial panic threw the city into such confusion that many business houses closed their doors, and thousands of unemployed soon walked the streets. A general shutdown of mills and factories increased the number of idle workers and the general unrest. A mass meeting of 10,000 workmen was held in Independence Square to demand action from State and municipal authorities toward remedying conditions. To combat these issues, Mayor Vaux instituted a public works and municipal improvements program and hired many of the unemployed.

While the depression that followed the panic of 1857 caused a general stagnation of business the following year, railway construction in the city continued on an increasing scale. No fewer than 14 charters were granted for the construction of railways, and workmen were kept busy tearing up streets and laying tracks. The West Philadelphia line on Market Street was put into operation. The Tenth and Eleventh Streets route and the lines on Spruce and Pine Streets and Chestnut and Walnut Streets were completed shortly afterward. Considerable opposition was displayed to the running of street cars on Sundays, but this difficulty was subsequently overcome.

West Philadelphia Line on Market Street.

The Zoological Society was formed in 1859, and Coleman Sellers made the first photographic motion pictures in 1860.

By the 1860s, the busy wharves provided service to private shipping lines, steamboats, and ferries that transported passengers and goods to and from Philadelphia and connected with the many rail lines now infiltrating the city. Warehouses, stores, and small hotels surrounded the docks. During the last quarter of the 19th century, factories and warehouses for foodstuffs, cotton and wool, paints, and drugs proliferated on the waterfront between Market and Vine Streets.

Before the Civil War, Philadelphia’s economic connections with the South made much of the city sympathetic to its grievances with the North. However, that changed when the war began in 1861, as many Philadelphians’ opinions shifted to support the Union and the war against the Confederate States. During the war, Philadelphia was an important source of troops, money, weapons, medical care, and supplies for the Union. More than 50 infantry and cavalry regiments, including the Washington Grays, were recruited wholly or partly in Philadelphia. The city was also the primary source of uniforms for the Union Army, manufactured weapons, and built warships. It also had the two largest military hospitals in the United States: Satterlee Hospital and Mower Hospital.

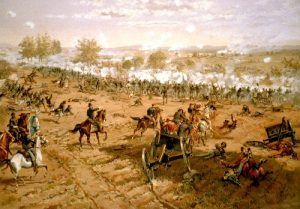

Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

In 1863, during the Gettysburg Campaign, Philadelphia was threatened by a Confederate invasion. Entrenchments were built to defend the city, but the Confederate Army was turned back at Wrightsville, Pennsylvania, and the Battle of Gettysburg. The main legacy of the Civil War in Philadelphia was the rise of the Republican Party. Despised before the war because of its anti-slavery position, the party created a political machine that would dominate Philadelphia politics for almost a century.

In 1865, the hospital building was converted into a factory. After the Civil War, two German Lutheran churches merged to become the St. Michael-Zion German Lutheran Church.

As the section of Old City south of Market Street grew in regional and national importance as a financial center, Philadelphians erected the Commercial Exchange Building, which housed the Chamber of Commerce, in 1867 and 1868. It occupied the site of the old Slate House, the colonial residence of William Penn and many other significant Philadelphians, at 135 S. 2nd Street. After a devastating fire in 1869, the building was rebuilt the following year. The Exchange Building was demolished in 1976 to make way for Welcome Park.

In 1871, construction began on the Second Empire-style Philadelphia City Hall on Center Square. It took more than 30 years to complete.

In 1875, the Central Delaware Market at Pier 11 functioned as a food and produce distribution center. Other industries nearby included a salt warehouse, a canning works, a hay and feed warehouse, and the Jayne Estate Building (1870) at the corner of Vine Street and Delaware Avenue, a venture of the estate of successful drug manufacturer Dr. David Jayne. This area continued to prosper through the end of the 19th century despite shifting away from maritime trades to distributing foodstuffs and domestic items.

As 1875 drew to a close, preparations were made to welcome the advent of the Nation’s centennial year. On New Year’s Eve, the city was ablaze with lights. A brilliant display of fireworks was set off at Southwark. Festivities were centered in the area from South Street to Girard Avenue and westward to the Schuylkill River.

Centennial Expedition in Fairmount Park, Currier & Ives, 1876.

The Centennial Exhibition, commemorating 100 years of American Independence, opened on May 10, 1876, in Fairmount Park. President and Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant, with Dom Pedro de Alcantara, Emperor of Brazil, and his wife as guests of honor, presided at the opening, which was attended by notables from all over the world and a crowd of 100,000. Thirty-eight foreign nations and 39 States and Territories were represented. Record attendance for a single day was reached on Pennsylvania Day, September 28, when 275.000 people passed through the turnstiles. On November 10, 1876, President Grant officially closed the exhibition. It was the first world fair held in the U.S.

In July 1877, the great railroad strike that spread throughout the country broke out in Philadelphia. Employees of the Reading and Pennsylvania Railroads organized in the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, struck for better wages and improved working conditions, such as full crews on all trains and the abolishment of the double train. There was little rioting, however, as police and the National Guard prevented major disorders. In Pennsylvania, the strike ended on July 27, after freight and passenger service had been suspended for a short time. The men returned to work, understanding that the issues would be settled by arbitration. Both sides claimed a victory.

By 1879, most of the modest three and four-story buildings on the two blocks had been replaced. By that time, ten new bank buildings had been erected. These included the Farmers’ and Mechanics’ Bank (1854-1855) and Bank of Pennsylvania (1857-1859), the First National Bank (1865-1867), the Pennsylvania Company for Insurance of Lives and Granting Annuities (1871-1873); the Philadelphia Trust, Safe Deposit, and Insurance Company (1873-1974); and the National Bank of the Republic (1883-1884) and Provident Life and Trust Company (1876-1879). The Corn Exchange National Bank occupied an impressive building at 125-135 Chestnut Street by 1879.

The building of three major railroad stations in the 1880s and 1890s, the Broad Street Station at 15th and Market Streets, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Station at 24th and Chestnut, and the Reading Terminal at 12th and Market, further encouraged the significant changes already underway in Old City.

Reading Terminal in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In 1892, the first trolley car was operated on Catharine and Bainbridge Streets. The Reading Terminal at 12th and Market Streets was opened the following year.

In 1893, Philadelphia’s first elevated rail line, the Northeast Elevated Railroad, was planned along Front Street to Market Street. A metal superstructure was erected on Front Street at Arch, but the plan was scrapped after citizens protested. In 1894, Broad Street became the first thoroughfare in the city to be paved with asphalt.

In 1897, the Commercial Museum was officially opened by President McKinley. The following year came the Spanish-American War, in which many Philadelphians and organizations, including the First City Troop, saw service.

The first motor car to appear in the city was brought from France in 1899 by Jules Junker, a local merchant.

By 1900, the population exceeded one and a quarter million. The influx of immigrants from Europe and African Americans from the South, together with the steadily increasing birthrate, had transformed the city proper into many people living in congested streets. The wealthier families began their departure to the city’s outlying districts and to the suburbs along the Main Line of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

20th Century

Broad Street in Philadelphia by Detroit Publishing, 1900.

By the 20th century, Philadelphia had an entrenched Republican political machine and a complacent population. Black newcomers in the 20th century were part of the Great Migration out of the rural South and into northern and midwestern industrial cities.

At that time, three ferries linked Philadelphia with New Jersey. The Philadelphia & Reading Railroad operated ferries out of a wharf at Chestnut Street; the Pennsylvania Railroad operated ferries out of wharves at Vine and Market Streets. During that decade, the plan for a passenger line was reinvigorated.

With the advent of the automobile, the city’s roughly paved streets, intended for horse-drawn vehicles, were replaced gradually by thoroughfares of asphalt.

In 1907, when the railroads began improving and enlarging their terminals with their extensive waterfront holdings, the City created a port authority known as the Department of Wharves, Docks, and Ferries. Under the direction of this Department, the City erected a series of new municipal piers. The Department concentrated its initial construction efforts on developing general cargo terminals linked to rail lines that could compete for business by offering spatial flexibility and speed of freight movement. The advanced new wharves were constructed with steel and concrete and ornamented with architectural embellishments.

Shibe Park, home of the Philadelphia American League baseball club, was opened in April 1908. The same year, Oscar Hammerstein’s Philadelphia Opera House was established, and the Y.M.C.A. was dedicated.

In 1909, regular passenger service over the new elevated Philadelphia & Reading Railroad tracks began from the Reading Terminal.

Motormen and conductors of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company declared a strike for higher wages in May 1909. Another followed in February 1910, when the men received instructions not to return to work until the company and the hourly wage rate recognized by their union increased from 20 to 25 cents. There was much rioting and disorder during the strike, which lasted about five months before an agreement was reached. Hundreds of cars were damaged, many people were injured, and numerous arrests of strikers and union officials were made.

In 1910, the first airplane flight from New York to Philadelphia was made by Charles K. Hamilton, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania opened its new building at 13th and Locust Streets; the Aquarium in Fairmount Park was completed; and the census of 1910 showed an increase of population to 1,549,008. The same year, a general strike shut down the entire city.

Philadelphia Trolley.

In 1911, Philadelphia had nearly 4,000 electric trolleys running on 86 lines.

World War I began on June 28, 1914, gradually heightening intensity in Philadelphia during the next four years. The war seemed very remote from the city until the steamship Lusitania was sunk by a German submarine on May 7, 1915. Then public sentiment, which had been rather divided in its sympathies for the belligerents, began to swing towards the Allies’ side. Meanwhile, Philadelphia industries were obtaining lucrative contracts for munitions and war materials from the Allied powers. Factories operated day and night to turn out their merchandise of death.

On January 22, 1917, the last contingent of Philadelphia troops, which had been sent to the Mexican border the previous July in the campaign against Pancho Villa, was ordered home. As if in preparation for the inevitable, many civilians joined the National Guard units, which were conducting practice battles and drills. Army and Navy recruiting stations were opened, and the Philadelphia Navy Yard was closed to the public. Expectations that America would enter the war grew stronger.

The city had just reached the height of its production of men, money, and war materials when news of the Armistice arrived on November 11, 1918. The months immediately following were occupied with celebrations of victory and the welcoming home of soldiers and sailors; the prevalent elation was dampened, however, by an epidemic of influenza, which caused thousands of deaths in the city.

In July 1919, Philadelphia was one of more than 36 industrial cities nationally to suffer a race riot during Red Summer in post-World War I unrest as recent immigrants competed with Blacks for jobs. In the 1920s, the public flouting of Prohibition laws, organized crime, mob violence, and corrupt police involvement in illegal activities led to the appointment of Brigadier General Smedley Butler of the U.S. Marine Corps as the city’s director of public safety. However, political pressure still prevented long-term success in fighting crime and corruption.

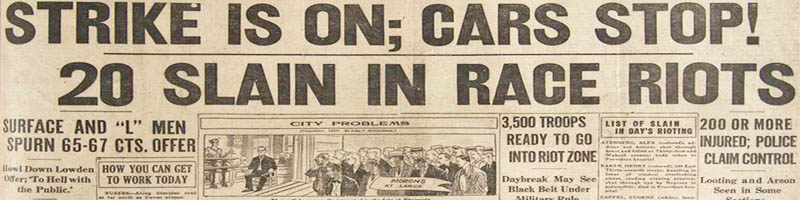

Red Summer Newspaper Headlines, July 1919.

In 1920, more than two million vehicles and 47 million passengers traveled between Old City and New Jersey. Within a few years, most commuters and other travelers bypassed Old City as they traveled by newer modes of transportation. The waterfront area declined as rail, automobile, and air transportation systems became popular.

With the advent of Prohibition that year, bootleggers, speakeasies, and gangsters quickly multiplied. Vice, racketeering, and official corruption increased to such an extent that in January 1924, at the request of Mayor W. Freeland Kendrick, Major General Smedley D. Butler obtained a leave of absence from the Marine Corps to accept the post of Director of Public Safety. General Butler led an intensive drive against organized crime for more than a year, whipping the police department and its personnel into greater efficiency.

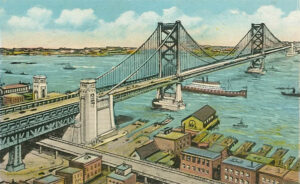

Benjamin Franklin Bridge in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The construction of the Delaware River Bridge began in January 1922 and was completed in 1926. At the time of its completion, it was the longest suspension span in the world and a technological and architectural marvel. Uniting New Jersey and Pennsylvania, the bridge signaled the ascension of the automobile, forever altering development in both states. The completion of the bridge resulted in the immediate demise of the thriving ferry businesses in the District. The bridge was renamed the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in 1955.

Work on the North Broad Street Subway started in August 1924.

The first commercial transatlantic telephone call between Philadelphia and London was made on January 29, 1927, when Josiah H. Penniman, provost of the University of Pennsylvania, spoke to Lord Dawson of Penn at the other end of the wire.

The Art Museum at the head of the Parkway opened on March 26, 1928, and the new Broad Street Subway opened on September 1 of that year.

The Tacony-Palmyra Bridge was opened on August 14, 1929, and the North Philadelphia Station of the Reading Railroad Company was dedicated on September 28.

Large-scale investment and construction dwindled after the stock market crash in October 1929. Not many could have foreseen that the next four years would be among the city’s darkest and hundreds of thousands of unemployed would walk the streets. However, small-scale, low-end wholesale companies, such as purveyors of inexpensive socks, and related service businesses, such as diners and taverns, survived in the neighborhood until the end of the 20th century.

In 1932, Philadelphia became home to the first modern International Style skyscraper in the United States, the PSFS Building, designed by George Howe and William Lescaze.

With the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, State liquor stores were opened in Philadelphia in 1934, providing employment to many people and increasing the state’s revenue.

Independence Day in Philadelphia, courtesy Visit Philadelphia.

In 1938, the celebration of the Declaration of Independence was formalized as Independence Day, one of only ten designated U.S. federal holidays.

In 1940, non-Hispanic whites constituted 86.8% of the city’s population. In 1950, the population peaked at 2,071,605. Afterward, it began to decline with industry restructuring, leading to the loss of many middle-class union jobs. In addition, suburbanization enticed many affluent residents to depart the city for its outlying railroad-commuting towns and newer housing. The resulting reduction in Philadelphia’s tax base and local government resources caused the city to struggle through a long adjustment period.

Historic areas such as Old City and Society Hill were renovated during the reformist mayoral era of the 1950s through the 1980s, making both areas among the most desirable Center City neighborhoods.

The Philadelphia Historical Commission was created in 1955 to preserve the cultural and architectural history of the city. The commission maintains the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, adding historic buildings, structures, sites, objects, and districts as it sees fit.

The construction of Interstate 95, part of the post-war highway boom, was approved by the federal government as part of the Interstate Highway Act in 1956. Work finally began on the section of the highway running through downtown Philadelphia in the late 1960s and was completed in the 1970s. Its construction necessitated the demolition of hundreds of historic buildings. The highway facilitated the development of automobile suburbs and truck transportation throughout the Delaware Valley, resulting in the further stagnation of Old City, which no longer enjoyed an advantage as the region’s transportation hub.

Revitalization and gentrification of neighborhoods began in the late 1970s and continued into the 21st century, with much of the development occurring in the Center City and University City neighborhoods. However, this expanded the shortage of affordable housing in the city. Government resources caused the city to struggle through a long adjustment period, and it approached bankruptcy by the late 1980s.

The 548-foot-high City Hall remained the tallest building in the city until 1987 when One Liberty Place was completed. Beginning in the late 1980s, numerous glass and granite skyscrapers were built in Center City.

Aerial view of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, focusing on the skyscrapers of what locals call “Center City.” Photo by Carol Highsmith.

After many manufacturers and businesses left Philadelphia or shut down, the city started attracting service businesses and market itself more aggressively as a tourist destination.

In the second half of the 20th century, immigrants worldwide entered the U.S. through Philadelphia as their gateway. This led to a reversal of the city’s population decline between 1950 and 2000, during which it lost about 25% of its residents.

21st Century

Philadelphia began experiencing population growth in 2007, which has continued with gradual yearly increases through the present. In that year, Comcast Center surpassed One Liberty Place to become the city’s tallest building.

The city encompasses 142.71 square miles, of which 134.18 square miles is land and 8.53 square miles, or 6%, is water. Natural bodies of water include the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park lakes, and Cobbs, Wissahickon, and Pennypack Creeks. The largest artificial body of water is East Park Reservoir in Fairmount Park.

In 2015, Center City had an estimated 183,240 residents, making it the second-most populated downtown area in the United States after Midtown Manhattan in New York City.

The Comcast Technology Center, completed in 2018, is the tallest building in the United States outside of Manhattan and Chicago, reaching 1,121 feet.