Potlach Ceremony of Native Americans – Legends of America (original) (raw)

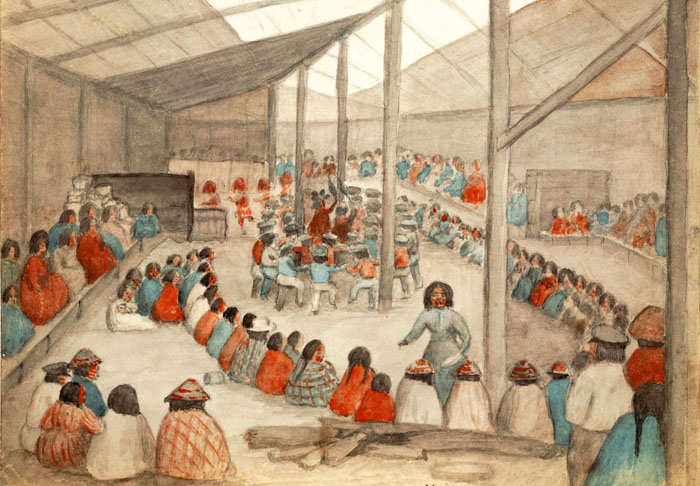

Potlatch Ceremony by James G. Swan

A Potlach Ceremony is an opulent gift-giving ceremonial feast to celebrate an important event held by tribes of Northwest Indians of North America, including the Tlingit, Tsimishian, Haida, Coast Salish, Chinook, and Dene people. The term ‘Potlatch’ was taken from a Nootka Indian word meaning “gift.”

The ceremony celebrated a change of rank or status with dancing, feasting, and gifts. Those of the Northwest Coast associated prestige with wealth, and the potlatcher gained prestige according to how liberally he gave.

Held on the occasion of births, deaths, adoptions, marriages, and initiations into secret societies, Potlatches were also held for more miner events because the main purpose of the ceremony was not the occasion itself but the validation of claims to social rank. It was sometimes also used as a face-saving device by individuals who had suffered public embarrassment or as a means of competition between rivals in social rank.

Potlatch ceremonies were typically practiced more in the winter, as individuals procured wealth for the family, clan, or village during the warmer months. The ceremony often involved music, dancing, singing, storytelling, speeches, and games. The honoring of the supernatural and the recitation of oral histories are a central part of many potlatches.

Gifts included storable food, canoes, slaves, and ornamental “coppers,” which were sheets of beaten copper, considered the equivalent of a slave. They were only ever owned by individual aristocrats.

The distribution of goods by the donor was made according to the social rank of the recipients. The size of the gatherings reflected the rank of the donor, and the efforts of the kin group of the host were exerted to maximize the generosity. The proceedings gave wide publicity to the social status of donors and recipients because there were many witnesses.

In addition to giving away or destroying wealth to demonstrate a leader’s wealth and power, potlatch ceremonies also reaffirmed family, clan, connections with other tribes and connection with the supernatural world.

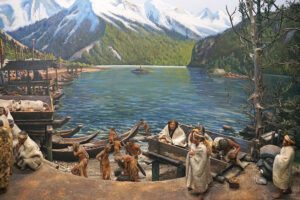

Kwakiutl Indians in British Columbia, a diorama at the Milwaukee Public Museum in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

A true chief “always died poor” because he had potlatched his wealth. However, he died rich in rank and honor, which would pass on to his family, heirs, and descendants.

When Europeans arrived, they found that this social system, based on the distribution of wealth, was very alien. It soon came under attack by missionaries and government officials who felt the accumulation of goods for giving away would produce indigence and thriftlessness.

“It is not possible,” wrote an early commentator, “that the Indian can acquire property or can become industrious with any good result while under the influence of this mania.”

Such reasoning led the Canadian government to ban the ceremony.

The potlatch reached its most elaborate development among the southern Kwakiutl from 1849 to 1925.

Many other tribes, especially among the Plains Indians, also traditionally practiced some form of potlatch, or giveaway ceremonies and customs, sometimes lavishly distributing goods and food to other clans, villages, or tribes.

The potlatch has re-emerged in some communities and remains in others, such as the Haida Nation, which has rooted its democracy in potlatch law.

“In the potlatch, the host, in effect, challenged a guest chieftain to exceed him in his ‘power’ to give away or to destroy goods. If the guest did not return 100 percent on the gifts received and destroy even more wealth in a bigger and better bonfire, he and his people lost face and so his ‘power’ was diminished.”

— Dorothy Johansen, American historian of the Pacific Northwest.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2023.

Also See:

Native American Photo Galleries

Native Americans – The First Owners of America

Native American Index of Tribes

Sources: