Prohibition in the United States – Legends of America (original) (raw)

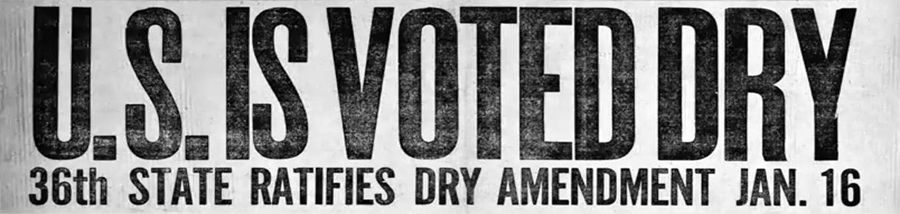

United States Voted Dry

“The reign of tears is over. The slums will soon be a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs. Men will walk upright now, women will smile, and children will laugh. Hell will be forever for rent.” – Reverend Billy Sunday at the beginning of Prohibition

Prohibition in the United States was a nationwide constitutional ban on the production, import, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages that lasted from 1920 to 1933.

As the years in American History moved forward into the 20th century, the days of the Old West were winding down. Railroads replaced stagecoaches, the growth of cities was bringing culture to the West, most of the notorious outlaws were dead or in jail, and Wyatt Earp had settled down to tell his frontier tales to any and every book author and silent movie producer in Hollywood.

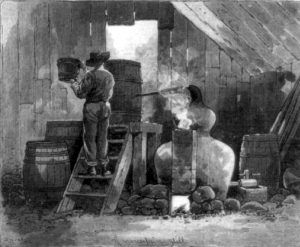

Temperance Movement, by S.B. Morton, 1874.

Meanwhile, as the savage West was slowly being tamed, a new movement had been emerging in the East to curb or stop the consumption of alcohol. Often associated with poverty, crime, corruption, social problems, and tax burdens, alcohol was considered the source of all evil by those behind the Temperance and Prohibition movements. Saloons were accused of being dens of iniquity by those behind the movements, a fact that was most often true.

Temperance advocates started in the 1830s. They didn’t initially support prohibiting alcohol consumption but rather moderation of beer and wine and abstention from hard liquor. In 1851, Maine prohibited the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors. Four years later, in 1855, 13 of the then-31 states passed similar laws.

During Prohibition, Pabst Brewing switched to cheese, soft drinks, and malt extract to stay in business. After the prohibition ended, Pabst sold the cheese operation to Kraft and went back to making beer and putting blue silk ribbons on the bottles. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

However, when the soldiers returned from the Civil War, many of whom had been exposed to alcohol for the first time, these hardened warriors wanted nothing to do with this movement and it was given little attention for the next two decades. In fact, many saloons were gaining even more popularity among those very same soldiers and other men moving westward in search of fortune, land, and adventure. New saloons sprouted up by the hundreds in the mining camps and new settlements on the vast frontier. Here, where miners, cattlemen, and outlaws reigned, and the number of men far outweighed those of women, it was a “man’s world,” where saloons were often their only source of entertainment.

It wouldn’t be until women began to arrive in the West that the views of saloons would begin to change. Barred from these many drinking establishments, “proper” women began to see saloons as hotbeds of vice, where not only drinking was encouraged but also gambling, prostitution, dancing, and tobacco use. Becoming politically active for the first time, women joined the fight in the 1880s and the cause was reborn.

Prohibition Poster

A decade later, the views of the temperance movement changed from alcohol in moderation to total Prohibition and many of its supporters were to be found in politics and on school boards, where they flooded young children with anti-alcohol materials. Supported primarily by the middle class and the very women that saloons had long disallowed, the movement gained national attention by the turn on the century.

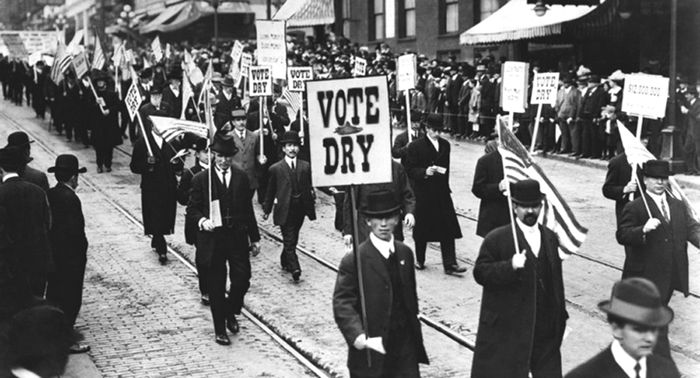

Positive that alcohol was the bane of all evil and the main impetus for the fall of American morals, members of the Anti-Saloon League and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union began to march in the streets, halting traffic with their demands that saloons close their doors. Within a few short years, the “frenzy” of these groups grew to include a political movement where large numbers of voters demanded that the government lead the country in a strong stand of moral leadership.

One of the movement’s first results was expensive licensing rates for taverns and a cessation of new permits in many areas. In many cities, bars were required to segregate themselves in certain areas away from residences and more influential businesses.

In addition, some cities banned the “free lunch table” and eliminated mustache towels. As the movement gained momentum and the restrictions became tougher, the traditional saloon progressively saw a downward decline in the years before Prohibition.

Anti Saloon League

By 1916, 21 states had banned saloons, and national elections returned more members to Congress who favored Prohibition than those favoring “wet” laws, outnumbering their opponents two-to-one. Immersed in World War I, the vast majority of the American Public favored the amendment and considered it unpatriotic to use much-needed grain to produce alcohol. Furthermore, many of the large brewers and distillers were of German origin, which added the additional support of many.

A woman gets her husband to sign a pledge not to drink, 1906

Business leaders believed their workers would be more productive if alcohol could be withheld from them. John D. Rockefeller alone donated over $350,000 to the Anti-Saloon League, and Henry Ford boldly announced, “The country couldn’t run without Prohibition. That is the industrial fact.”

On December 18, 1917, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, which prohibited the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” was drafted and passed by Congress and sent to the states for ratification. Called the “noble experiment” by Herbert Hoover, 75% of the states approved the amendment, and it was ratified on January 16, 1919. In 1920, the Volstead Act was passed to enforce the amendment.

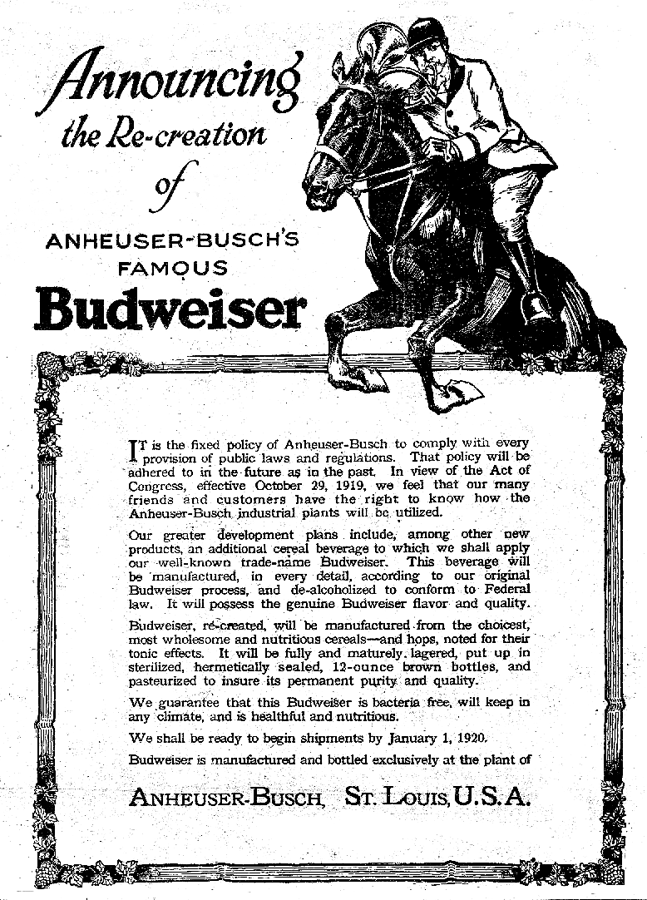

Budweiser ad announcing their reformulation of Budweiser as required under Prohibition, 1919.

The law devastated the nation’s brewing industry, closing large industries in St. Louis, Milwaukee, Chicago, and numerous other cities. But Prohibition advocates cared little about that, rejoicing in their initial their “successes,” as arrests for drunkenness declined and medical statistics showed a marked decrease in treatments for alcohol-related illnesses. One of the first effects of the new amendment was placing thousands of people out of work, from brewery employees to bartenders to grape growers in California.

Statistics also demonstrated that drinking, in general, decreased. However, the decline had been the trend for several years before Prohibition, and many felt that any further decrease was due to the high cost of bootlegged liquor rather than the law itself. Prohibition maintained some of its success for a time, especially in rural areas, though liquor continued to flow with relative ease in the cities.

However, with World War I ending and the nation in high spirits, the demand for liquor quickly increased. Another culture emerged for those who saw an opportunity and financial gain in thwarting the new law and filling the public demand. Bootleggers, illegal alcohol traffickers, and speakeasies began to multiply by the hundreds.

Moonshiner making alcohol in a still in North Carolina.

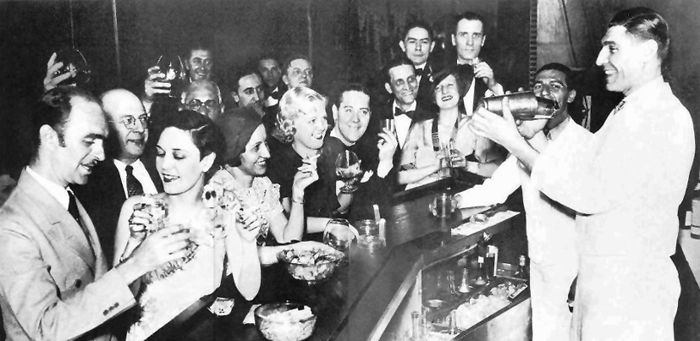

Before the amendment, women drank very little, and even then, perhaps just a bit of wine or sherry. Just six months after Prohibition became law in 1920, women got the right to vote, and coming into their own, they quickly “loosened” up, tossed their corsets, and enjoyed their newfound freedoms. The “Jazz Age” quickly signified a loosening up of morals, the exact opposite of what its Prohibition advocates had intended, and in came the “flapper.” They flooded the speakeasies with short skirts and bobbed hair, daring to smoke cigarettes and drink cocktails. Dancing to the tunes of such soon-to-be-famous jazz greats as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Bojangles Robinson, and Ethel Waters, their powdered faces, bright red lips, and bare arms and legs displayed an abandon never before seen by American women. Quickly, both Prohibition and jazz music were blamed for the immorality of women, and young people were attracted to the glamour of speakeasies and began to drink in large numbers. Songwriter Hoagy Carmichael described the new era as: it came in “with a bang of bad booze, flappers with bare legs, jangled morals and wild weekends.”

Organization was required to supply these many illegal establishments with beer, wine, and liquor, hence the birth of organized crime. Into this crime-ripe environment walked such characters as Al “Scarface” Capone in Chicago, the Purple Gang of Detroit, Lucky Luciano in New York, and hundreds of others. The largest majority of speakeasies were established and controlled by organized crime, which opened everything from plush nightclubs to dark and smoky basement taverns.

Prohibition officers raiding a lunchroom in Washington DC, 1923.

When I sell liquor, it’s bootlegging.

When my patrons serve it on a silver tray on Lakeshore Drive, it’s hospitality.

— Al Capone

Though raids became a daily federal pastime, law enforcement couldn’t keep up. When the enforcers were successful in targeting a “gin joint,” the anticipating club owners were often able to disguise the true intent of their businesses, installing elaborate alarms and hiding their illegal contraband in drop shelves and secret cabinets. Other establishments didn’t even bother with hiding or disguising the liquor, as they paid out part of their profits to Prohibition agents and police officers, leading to a monumental amount of political corruption.

Increasingly, organized crime groups controlled the liquor industry, which led to turf wars and gang murders, the worst of which was the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre of 1929 in Chicago. Blamed on Al Capone, seven men were killed in the increasingly violent war over liquor control. Though gaining the most attention, this was just one violent event of the era, as, by the late 1920s, Chicago authorities reported as many as 400 gangland murders each year. Chicago was not alone in its high crime rate, as virtually every city across the nation was rife with illegal liquor trafficking, speakeasies, and the violence that they bred.

Bootlegger’s car captured, 1922

Bootleggers were crafty, finding all sorts of ways to transport and hide liquor as boats laden with hooch from Mexico and Canada lined up along the coasts. Hidden under produce, in crates labeled with other products, in coconut shells, and garden hoses, the liquor moved inland. While most of the breweries shut down operations, others continued to produce what was nick-named “near beer,” which held an alcohol content of less than one-half-of-one percent, which was still legal. Amazingly, a monumental amount of “real beer” came from these same breweries.

California grape growers were even more creative, as many stopped making wine and began to produce a grape juice product called Vine-Glo. The literature that was provided with the juice carefully warned its buyers of what they shouldn’t do with the juice because if they did, it would turn into wine within a couple of months. Within seven years between 1919 and 1926, land utilized for growing grapes expanded in California nearly seven times.

On a smaller scale, individuals also found creative ways to hide their liquor in hip flasks, hot water bottles, hollowed-out canes, and false books. At the same time, medicinal alcohol was still legal, and the sale of patent medicines, elixirs, and tonics dramatically increased. Overnight, thousands of otherwise “decent, law-abiding” citizens became criminals.

1920s Speakeasy.

Another setback for prohibitionists was their loss of control over the location of drinking establishments. Where before, ordinances and licensing laws were utilized to limit alcohol sales on Sundays, election days, and in certain neighborhoods, illegal speakeasies sprouted up everywhere without limitation on their hours. Serious crime rates, which had been falling during the first part of the century gradually reversed itself during Prohibition, as homicides, burglary, and assault increased, and the prisons became overcrowded due to those incarcerated for alcohol-related crimes. In no time, American prisons were suffering from extreme overcrowding.

Repeal the Prohibition Amendment.

As the newspaper headlines across the country screamed violent headlines, the public increasingly blamed Prohibition for the violence, as well as the political corruption that had become rampant across the country. Placing the matter within the jurisdiction of the Treasury Department for enforcement, its untrained Prohibition officers faced huge challenges in budget constraints and little support from the public. Before long, groups began to organize to repeal Prohibition, especially after the Great Depression, when people were looking for jobs, ones that would be created if breweries, distilleries, and taverns could reopen. Even Herbert Hoover was forced to admit that the 18th Amendment offered more harm than good.

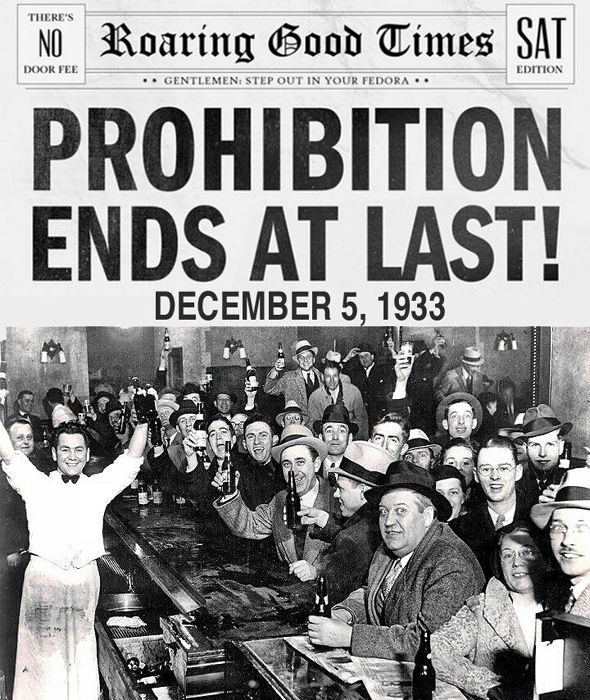

By 1932, both presidential candidates, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover, favored repeal. When elected, Roosevelt backed the repeal, and on December 5, 1933, the 21st Amendment to the Constitution officially repealed the 18th Amendment, ending the “Noble Experiment.”

When prohibition finally ended, the word “saloon” virtually disappeared from American vocabulary, and legal establishments once again opened in abundance, referring to themselves as “cocktail lounges” and “taverns.”

Prohibition Ends, 1933

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2024.

Also See:

Gangsters, Mobsters & Outlaws of the 20th Century

Speakeasies of the Prohibition Era

Sources:

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco & Firearms

Government Archives

Library of Congress

Wikipedia