Ashtabula Train Wreck – Historic Accounts – Legends of America (original) (raw)

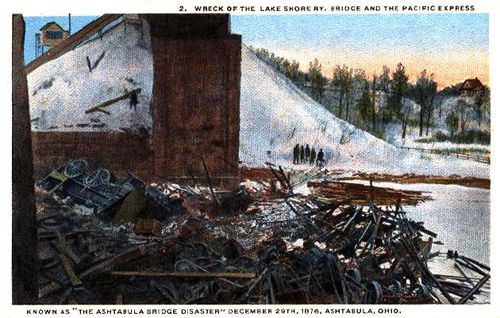

Wreck of the Pacific Express Ashtabula Bridge Disaster, 1876.

The Ashtabula, Ohio Railroad Disaster, often called the Ashtabula Disaster or the Ashtabula Horror, was one of the worst railroad disasters in American history. The event occurred on December 29, 1876, when a Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway Train, the Pacific Express, plunged into the Ashtabula River, about 100 yards from the railroad station at Ashtabula, Ohio. It’s topped only by the Great Train Wreck of 1918 in Nashville, Tennessee.

More than 90 of its 159 passengers and crew were killed when the bridge collapsed, and the train fell some 70 feet into the river below before igniting into a roiling ball of fire.

The bridge, designed jointly by Charles Collins and Amasa Stone, both of whom committed suicide, was the first Howe-type wrought iron truss bridge built. Though Collins was reluctant to proceed with the project because he felt it was still “too experimental,” higher powers prevailed; the bridge was built and lasted only 11 years before it collapsed.

Historical Accounts:

Chicago Tribune – December 30, 1876

The proportions of the Ashtabula horror are now approximately known. Daylight, which allowed finding and enumerating the saved, reveals the fact that two out of every three passengers on the fated train are lost. Of the 160 passengers whom the maimed conductor reports as having been on board, 59 can be found or accounted for. The remaining 100, burned to ashes or shapeless lumps of charred flesh, lie under the ruins of the bridge and train.

The disaster was dramatically complete. No element of horror was wanting. First, the crash of the bridge, the agonizing moments of suspense as the seven laden cars plunged down their fearful leap to the icy river-bed; then the fire, which came to devour all that had been left alive by the crash; then the water, which gurgled up from under the broken ice and offered another form of death, and, finally, the biting blast filled with snow, which froze and benumbed those who had escaped water and fire. It was an ideal tragedy.

The scene of the accident was the valley of the creek, which, flowing down past the eastern margin of Ashtabula village, passes under the railway three or four hundred yards east of the station. A long wooden trestlework lasted for many years after Lake Shore Road was built. Still, as the road was improved, this was superseded about ten years ago with an iron Howe truss, built at the Cleveland shops and resting at either end upon high stone piers flanked by heavy earthen embankments. The iron structure was a single span of 159 feet, crossed by a double track seventy feet above the water, which at that point is now from three to six feet deep and covered with eight inches of ice. The descent into the valley on either side is precipitous, and, as the hills and slopes are piled with heavy drifts of snow, there was no little difficulty in reaching the wreck after the disaster became known.

The disaster occurred shortly before eight o’clock. It was the wildest winter night of the year. Three hours behind its time, the Pacific Express, which had left New York the night before, struggled along through the drifts and the blinding storm. The eleven cars were a heavy burden to the two engines, and when the leading locomotive broke through the drifts beyond the ravine and rolled on across the bridge, the train was moving at less than ten miles an hour. The headlamp threw, but a short and dim flash of light in the front so thick was the air with the driving snow. The train crept across the bridge, the leading engine had reached solid ground beyond, and its driver had just given it steam when something in the under gearing of the bridge snapped.

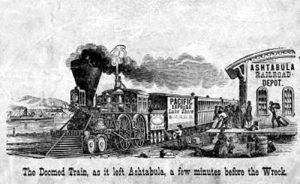

19th Century illustration of the Ashtabula Disaster.

For an instant, there was a confused crackling of beams and girders, ending with a tremendous crash, as the whole train but the leading engine broke through the framework and fell in a heap of crushed and splintered ruins at the bottom. Notwithstanding the wind and storm, the crash was heard by people within doors half a mile away. For a moment, there was silence, a stunned sensation among the survivors, who, in all stages of mutilation, lay piled among the dying and dead. Then arose the cries of the maimed and suffering; the few who remained unhurt hastened to escape from the shattered cars. They crawled out of windows into freezing water waist-deep. Men, women, and children, with limbs bruised and broken, pinched between timbers and transfixed by jagged splinters, begged with their last breath for aid that no human power could give.

Five minutes after the train fell, the fire in the cars piled against the abutments at either end broke out. A moment later, flames broke from the smoking car, and the first coach piled across each other near the middle of the stream. In less than ten minutes after the catastrophe, every car in the wreck was on fire, and the flames, fed by the dry varnished work and fanned by the icy gale, licked up the ruins as though they had been tinder. Destruction was so swift that mercy was baffled. Men who, in the bewilderment of the shock, sprang out and reached solid ice went back after wives and children and found them suffocating and roasting in the flames.

The neighboring residents, startled by the crash, were lighted to the scene by the conflagration, which made even their prompt assistance too late. By midnight, the cremation was complete. The storm had subsided, but the wind still blew fiercely, and the cold was more intense. When morning came, all that remained of the Pacific Express was a row of car wheels, axles, brake irons, truck frames, and twisted rails lying in a black pool at the bottom of the gorge. The wood had burned completely away, and the ruins were covered with white ashes. Here and there, a mass of charred, smoldering substance sent up a little cloud of sickening vapor, which said that it was human flesh slowly yielding to the corrosion of the fires. On the crest of the western abutment, half-buried in the snow, stood the rescued locomotive, all that remained of the fated train. As the bridge fell, its driver had given it a quick head of steam, which tore the draw head from its tender, and the liberated engine shot forward and buried itself in the snow. The other locomotive, drawn backward by the falling train, tumbled over the pier and fell bottom upward on the express car next behind. The engineer, Folsom, escaped with a broken leg; how he cannot tell, nor can anyone else imagine.

There is no death list to report. There can be none until the list of the missing ones who traveled by the Lake Shore Road on Friday is made up. No remains can ever be identified. The three charred, shapeless lumps recovered up to noon today are beyond all hope of recognition. Old or young, male or female, black or white, no man can tell. They are alike in the crucible of death. For the rest, there are piles of white ashes that glisten the crumbling particles of calcined bones; in other places, masses of black, charred debris, half underwater, may contain fragments of bodies but nothing of human semblance. It is thought that there may be a few corpses under the ice, as there were women and children who sprang into the water and sank, but none have been thus far recovered.

Cleveland Leader – December 30, 1876

Ashtabula doomed train.

The haggard dawn, which drove the darkness out of this valley of the shadow of death, seldom saw a ghastlier sight than was revealed with the coming of the morning. On either side of the ravine frowned the dark and bare arches from which the treacherous timbers had fallen, while at their base, the great heaps of ruins covered the one hundred men, women, and children who had so suddenly been called to their death. The three charred bodies lay where they had been placed in the hurry and confusion of the night. Piles of iron lay on the thick ice or bedded in the shallow water of the stream. The fires smoldered in great heaps, where many of the hapless victims had been all consumed, while men went about in wild excitement, seeking some trace of a lost one among the wounded or dead.

The list of saved and wounded having already been sent, the sad task remains of discovering who may be among the dead. The latter task will be the most difficult of all until the continued absence of here and there a friend will allow of but one explanation – that he was among those who took this fatal leap.

All the witnesses so far agree to the main facts of the accident. It was about 8 o’clock, and the train was moving along at a moderate rate of speed, the Ashtabula station being just this side of the ravine. Suddenly, and without warning, the train plunged into the abyss, the forward locomotive alone getting across safely. Almost instantly, the lamps and stoves set fire to the cars, and many who were doubtlessly only stunned and who might otherwise have been saved fell victim to the fury of the flames.

On the arrival of the Cleveland train, the surgeon of the road organized his corps of assistants and made a tour of the various hotels where the wounded were attended to, such help being given to each as was possible. The people of Ashtabula lent a willing hand, and all that human skill and money could do to save life or ease pain was done. The train that came from Cleveland for the purpose was immediately backed into position, and long before daylight, the least wounded were being prepared for transportation to Cleveland to be sent to hospitals or their homes.

The scenes among the wounded were as suggestive as the wreck in the valley. The two hotels nearest the station contained most of these, as they were scattered about on temporary beds on the floors of the dining rooms, parlors, and offices. In one place, a man with a broken leg would be under the hands of a surgeon, who rapidly and skillfully went at his work.

In another, a man covered with bruises and spotted over with pieces of plaster would look as though he had been snowed upon, except when the dark lines of blood across his face or limb told a different story. In some other corner, a poor woman moaned from the pain that she could not conceal, while overall, there brooded that hushed feeling of awe that always accompanies the calamities of this character.

Towards morning, the cold increased, and the wind blew a fearful gale which, with the snow that had drifted waist-deep at points along the line, made all work extremely difficult.

At 6 o’clock, the beds in the sleeping car of the special train were made up, and such of the wounded as could be moved were transferred there.

Harper’s Weekly Magazine – January 20, 1877

Ashtabula Disaster, Harper’s Weekly, January 1877

Our illustration shows the scene of the terrible railroad accident at Ashtabula Creek on the night of December 29, 1876. The train, consisting of eleven cars drawn by two engines, reached the bridge over Ashtabula Creek at about eight o’clock and was moving at a low rate of speed. The engines had crossed in safety when the bridge, without warning, gave way, and the whole train, except the leading engine, the couplings of which broke, was precipitated into the ravine, a distance of seventy-five feet. The banks are steep, and the furious snowstorm raging for several hours made it difficult for those who hastened to the disaster scene to reach the wreck. To add to the horror of the situation, the cars took fire from the stoves, and many passengers who were not killed outright by the fall were burned to death. Imprisoned by heavy fragments of the broken cars or unable to move on account of injuries, men, women, and children met death in this agonizing form. Some, it is supposed, were drowned.

Help arrived early from Ashtabula village, but nothing could then be done to save lives except to remove the wounded, who had already been taken from the cars to places where they could have surgical attention. The heat from the burning wreck was intense, and in the moment’s confusion, the means that might have been used to extinguish the flames were not thought of until too late. At the water-works, within 150 yards of the burning cars, lay 500 feet of hose, the coupling of which exactly fitted a plug within pistol-shot of the fire, the plug being connected with a powerful pumping apparatus, and there being sixty pounds of steam in the pump boiler. The hose could have been pouring a stream on the fire within five minutes, but for somebody’s fault or stupidity.

A disaster survivor, Mr. Burchell of Chicago, describes the scene vividly: “The first thing I heard was a cracking in the front part of the car, and then the same cracking in the rear. Then came another cracking in the front louder than the first, and then came a sickening oscillation and a sudden sinking, and I was thrown stunned from my seat. I heard the cracking and splintering and smashing around me. The ironwork bent and twisted like snakes, and everything took horrid shapes. I heard a lady scream in anguish, Oh! help me!’ Then I heard the cry of fire. Someone broke a window, and I pushed the lady out who had screamed. I think her name was Miss Bingham. The train lay in the valley in the water, our car a little on its side, both ends broken in. The rest of the train lay in every direction, some on end, some on the side, crushed and broken. The snow in the valley was nearly to my waist, and I could only move with difficulty. The wreck was then on fire. The wind blew from the east and whirling, blinding snow over the terrible ruin. The crackling of the flames, the whistling wind, and the screaming of the hurt made pandemonium in that little valley, and the water of the freezing creek was red with blood or black with the flying cinders.

The number of persons killed can not be accurately stated, as it is not known exactly how many there were on the train, and it is supposed that some bodies were entirely consumed in the flames. The official list of the killed and those who have died of their injuries gives the number as fifty-five, but it is supposed to be somewhat higher.

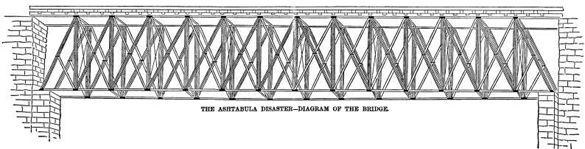

On this page, we give a diagram showing the construction of the iron bridge. It was built about eleven years ago and was supposed to be a structure of great strength. It had been tested with the weight of six locomotives; heavy trains had crossed on both its tracks simultaneously; it was believed to be well constructed of the best materials. Yet suddenly, it fell under a weight far below its tested strength. No wonder the traveling public anxiously inquired, “What was the cause?” Was it improperly constructed? Was the iron of inferior quality? After eleven years of service, had it suddenly lost its strength? Or had a gradual weakness grown upon it unperceived? Might frequent and proper examination have discovered that weakness? Or was the breakage the sudden effect of intense cold? If so, why had it not happened before in yet more severe weather? Is there no method of making iron bridges that ensure safety? And who is responsible (so far as human responsibility goes) for such an accident—the engineer who designed the bridge, the contractor, the builders, or the railroad corporation? Was the bridge, when made, the best of its kind or the cheapest of its kind? Was the contract for the building “let to the lowest bidder” or given to the most honest, thorough workmen? These and a hundred similar queries arise in every thoughtful mind, and an anxious community desires information and safety assurance. Most people can not, of course, understand the detailed construction of bridges. Still, they do desire confidence in engineers, builders, contractors, and manufacturers who make them and in the railroad companies, into whose hands they are constantly putting their own lives and the lives of those dearest to them.

Illustration from Harper’s Weekly, January 1877.

New York Times, December 29, 1890

The Story of a Disaster — Anniversary of the Ashtabula Railroad Wreck — A Terrible Night and a Terrible Loss of Life–How a Relief Train Started From Cleveland–The Scene at Ashtabula Bridge.

The Story of a Disaster — Anniversary of the Ashtabula Railroad Wreck — A Terrible Night and a Terrible Loss of Life–How a Relief Train Started From Cleveland–The Scene at Ashtabula Bridge.

No man who witnessed any portion of the terrible railroad disaster at Ashtabula Bridge on the evening of Friday, December 29, 1876– 14 years ago today– will lightly recall that event, nor will the pictures there displayed soon fade from his memory. The night itself was one not easily forgotten.

The wind filled the thoroughfares with pelting hailstones and snow, piled huge drifts upon one street corner, and swept the stones bare at another; the unsteady lamps flickered and went out; the cold was intense, and those who had business abroad made short work of it, and with faces set against the blast made such headway as they might for shelter. The trains from the East and West were late, and the few persons who waited for the Pacific Express stood grimly about the Union Station at Cleveland, expecting the tedium of a long vigil but with no premonition of the death harvest already reaped a little to the eastward.

Out of the storm’s grasp, a mite of a Western Union messenger boy was blown into the office of a Cleveland daily newspaper. He shook the snow from his rubber coat, cleared his eyes from a film of ice, and drew from his pocket a slip of paper, which he handed to the city editor and which read as follows:

9 p.m., December 29, 1876

The Pacific Express, Lake Shore Road, westward bound, has gone through the bridge at Ashtabula and is burning in the gorge 70 feet below. Can I help you in any way?

George Lowe, Night Manager

There were various sharp suggestions in this, and the room certainly for all the emotions of fear and horror the human mind can carry, but to the little group of men who heard it read, there was one pressing idea that for the time threw all else into the background–work: and that of a decisive and effective character. Some were sent their way upon varied lines of investigation. At the same time, to the writer of this fell the not-inviting but truly exciting task of finding a place upon the relief train, sure to be sent, and of tying the office and the wreck together by telegraph at the earliest possible moment.

It was a hard race to the Union Station against the driving storm. The little telegraph office by the entrance was filled with operators, trainmen, and physicians who had been summoned from all directions and officers of the road. Here was Charles Couch, Superintendent of the Erie Division, pale but clear-headed and giving orders in a manner that insured immediate obedience; Henry Stager, on whom fell the care of the dead or wounded upon all parts of the road; Charles Collin, the chief engineer, who knew ad few men did the defects of that bridge, but powerless to repair them, had been listening for this very crash for years — poor Collins, who locked himself into his bedroom and blew his brains out while the inquest was in progress rather than tell the world all he believed he knew.

The relief train was already making up in the station yard, while a pony engine had been sent to Glenville for Mr. Paine, Superintendent on the road. It was announced that a start would be made as soon as possible. The telegraph now and then gave a morsel of news to the silent and heavy-hearted groups in waiting; sometimes, the number killed and wounded would be lessened and then increase; the slow progress at the wreck was told, how the pitiable excuse of the engine from Ashtabula had been dragged through snow and storm, only to stand useless and unused upon the brink of the chasm; how the scores of wounded were being carried up the steep banks to places of shelter; how the flames were finishing the work of destruction wrought by the fall; and how the people of the little town were working like heroes to save such lives and prevent as much suffering as possible.

An hour of suspense dragged by, and still no sign of the engine that had been sent plowing through the drifts for Mr. Paine. The depth of the snow and the slippery tracks kept the locomotive moving at a snail’s pace at best, while frequently, the men upon it were compelled to shovel a path before it. But the run was completed at last, and when it crept into the station’s eastern doors, all was ready for the desperate fight against the elements that the relief train must make before Ashtabula could be reached.

The clock pointed to a few minutes after 10 when the one relief car — all the Superintendent dared to attempt to carry — with its two heavy engines linked together ahead, started eastward in the very teeth of the gale. Several railroad officials, a half dozen surgeons, a brace of reporters, and three or four half-crazed men who had friends on board the wrecked train composed the relief party. Half a mile up the track, a halt showed that the snow was too deep even for the twain of giant engines. The trainmen were out at the front immediately up to their waists in the drift, and a gang of shovelmen was with them. Thus, the road was fought for, mile by mile, for the three and a half hours required for the run over the short stretch between Cleveland and Ashtabula. From Painesville, two engines had already been sent ahead, on telegraphic orders. They were breaking away over the last half of the run while the train was laboring upon the first, and consequently, progress from that point onward was not so difficult.

Twice halts were made at way stations to learn the latest of the wreck. The tragedy increased in proportion with each report. The gloom of those on board was deep enough at the start; it was terrible as the last half of the run was made. One man, a prosperous and cultured Cleveland businesses man, who had been t the Union Station waiting for the wrecked express, was on board, and all that he knew was that his wife and little daughter were on that train–but whether alive and safe, or wounded, or dead he had no means of learning. At each stop, he made desperate efforts to learn their condition, and it was not until he reached the wreck that he learned they were neither with the save nor the injured but had been crushed side by side and burned out of all recognition by the flames.

Twice halts were made at way stations to learn the latest of the wreck. The tragedy increased in proportion with each report. The gloom of those on board was deep enough at the start; it was terrible as the last half of the run was made. One man, a prosperous and cultured Cleveland businesses man, who had been t the Union Station waiting for the wrecked express, was on board, and all that he knew was that his wife and little daughter were on that train–but whether alive and safe, or wounded, or dead he had no means of learning. At each stop, he made desperate efforts to learn their condition, and it was not until he reached the wreck that he learned they were neither with the save nor the injured but had been crushed side by side and burned out of all recognition by the flames.

As the relief train drew toward Ashtabula, a flare of light against the sky and fitful clouds of smoke that veered with the winds above the abyss showed where the bridge had fallen. The steady gleam of a headlight upon the western abutment showed where the engine stood that only the lightning quickness of Daniel McGuire had saved from the fall, for two locomotives had hauled the train from Erie because of the heaviness of the road, and when the break came the engineer in front threw his whole weight upon the lever, and with a mighty lunge the old Socrates parted its couplings and rushed up the already sinking rails to safety. The force of the engine was such that the tender jumped from the track and lay helpless and broken on the stone arch that formed a portion of the bridge. it was to Daniel McGuire that “Pop” Folsom, as he was dragged from under the second engine, bruised, maimed, white-faced, and bleeding, cried out: “Another Angola Dan!” The Socrates was soon covered with snow and ice, the fire out, the sharp winds lashing in vain fury about it, and its headlight still shining serenely and lighting the track clear up to the little station.

The relief train was indeed one of relief. It brought skilled medical and surgical aid, the authority that could assume responsibility and bring order out of chaos, cheers to those who could be moved and who were already longing for home, and facilities by which the anxious thousands all over the land could learn whether their friends aboard the train were numbered among the living or the dead.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024. The article not verbatim, as it has been very edited, primarily for spelling and grammatical corrections.

Also See: