Badlands National Park, South Dakota – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Badlands National Park, South Dakota, by Carol Highsmith.

“I was totally unprepared for that revelation called the Dakota Badlands.

What I saw gave me an indescribable sense of mysterious elsewhere.”

— Frank Lloyd Wright

South Dakota Badlands by Kathy Alexander.

Over 11,000 years of human history have been recorded in southwestern South Dakota’s Badlands National Park. Consisting of more than 244,000 acres of sharply eroded buttes, pinnacles, and spires, blended with the largest protected mixed-grass prairie in the United States, South Dakota’s Badlands are filled with legends, Indian Wars, gold mining, and ghost towns.

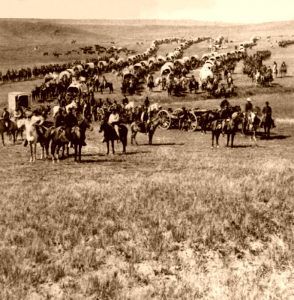

For centuries the Badlands have been met with a mix of dread and fascination, beginning with nomadic tribes who migrated into the area more than 10,000 years ago. Using the area as their hunting grounds, the first known inhabitants were the Paleo Indians, the mammoth hunters who were present at the end of the ice age. These were followed by the Arikara (or Ree) Indians in about 1500. The Cheyenne, Kiowa, Pawnee, Crow, and Sioux (or Lakota) migrated to the area around the 1700s. Following the buffalo that roamed the grasslands of the Great Plains, they survived the occasional harsh weather and difficult terrain by relying on the bison for almost every need. About a century and a half ago, the Great Sioux Nation had displaced the other tribes from the northern prairie, commanding more than 80 million acres in present-day South Dakota’s center.

The Lakota Sioux called the place “mako sica,” and early French trappers called it “les mauvaises terres a traverser,” both meaning “badlands.” Those very same French trappers would be the first of many Europeans who would, in time, supplant the Sioux, as they were soon followed by soldiers, miners, cattlemen, farmers, and homesteaders.

Sioux at an oasis in the Badlands.

At the close of the 18th century, the dominant Sioux were at the height of their power, with numerous interrelated bands comprised of three major tribes – the Yankton, Santee, and Teton. Exceptional horsemen, the Sioux were also skilled hunters and superior warriors.

When, in the 1700s, French-Canadian explorers began to come to the area, they were first met with friendliness as the native tribes traded with the Europeans. When Lewis and Clark made their trek in 1803, they met with little resistance when they passed through South Dakota.

However, as more and more pioneers began to encroach upon these lands, skirmishes began to occur between the Indians and the new white settlers. Into this midst came homesteaders, building farms and small towns, and some of Wild West’s most rough-and-ready characters, such as Jedediah Smith, Jim Bridger, Hugh Glass, and Thomas Fitzpatrick.

The Lakota never welcomed the white man to their hunting grounds, and as immigration increased, there was a marked decline in American Indian-white relations. The Army established outposts nearby, but they seldom entered the Black Hills. Trouble escalated when bands of Lakota began to raid nearby settlements before retreating to the Black Hills.

A homestead in Pennington County, South Dakota, by Arthur Rothstein, 1933.

When the U.S. Congress passed the Homestead Act in 1862, this brought a flood of emigrants into the Badlands, where they could purchase 160 acres for a token payment of about $18. As the push for western expansion continued, the Sioux retaliated more and more against the many settlers encroaching upon their lands, ultimately culminating with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

Establishing the Great Sioux Reservation, the treaty forever ceded all lands from the Missouri River west to the Bighorn Mountains of western Wyoming to the tribes. Agencies would distribute food, clothing, and money to the Sioux. The treaty prohibited settlers or miners from entering the Black Hills without authorization. In return, the Lakota agreed to cease hostilities against pioneers and people building the railroads. However, like most treaties made with the American Indians, it too would soon be broken.

George Armstrong led an expedition into the Black Hills in 1874.

By 1870 stories about gold and other wealth in the Black Hills began to circulate in Eastern South Dakota. Though the citizens of Yankton, South Dakota, pressed for an expedition, the Army and the Department of the Interior refused, trying to discourage any entry into the Hills. However, settlers continued to enter the Lakota reservation, and renewed Indian raids on nearby settlements caused General Philip Sheridan to propose an expedition to investigate the possibility of establishing a fort in the Black Hills in 1874. Led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, it would be the first official white expedition into the Black Hills, ostensibly to survey the uncharted region. Though the purpose was to find a suitable location for the fort, for unexplained reasons, a geologist and miners were included in the party. While the soldiers searched for a location for the fort, the miners searched for gold, and on June 30, 1874, the precious metal was discovered.

As the presence of gold leaked out, a flood of prospectors swarmed into the region. At the same time, federal troops futilely attempted to cordon off the Black Hills to protect tribal property boundaries. Negotiators in Washington, fearing war, encouraged the Sioux to sell the land, but repeated offers and talks failed.

The Pine Ridge Reservation of the Sioux is just outside the Badlands. Today, they see only the outline of their sacred Black Hills. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

Afterward, in 1875, the federal government ordered all tribal members to return to their reservations. Though harsh winter weather delayed the delivery of the message to many natives, the government designated those who did not comply with the order as “hostile.” In the spring, U.S. Army troops were assembled to round up all hostiles and return them to their reservations by force, if necessary.

In response, Hunkpapa Sioux leader and medicine man Sitting Bull summoned ten tribes of the Sioux, plus the Arapaho and Northern Cheyenne, to his camp in Montana Territory to discuss their options. By this time, the gold rush was full-blown, and approximately 10,000 white settlers were estimated to be populated in the Hills. Mining camps were established near Custer, Hill City, and Deadwood. New ones were found as old claims played out, and towns died or were born almost overnight.

Battle of the Little Bighorn by C.M. Russell

On June 25, 1876, in the valley of the Little Bighorn River, Sitting Bull and his 4,000 warriors were encamped when Custer and his troops came upon them. In an infamous decision, Custer elected to divide his command and mount an attack. Hopelessly outnumbered, Custer and his more than 200 soldiers were killed in less than twenty minutes. Congress reacted quickly and began punishing even the peaceful Sioux. Rations of food and clothing were cut dramatically, and a new treaty was eventually exacted, which ceded tribal land in the Black Hills to the federal government.

By the 1880s, homesteaders were busy farming, gold was harvested from the Black Hills, riverboats ran up and down the rivers, and railroad tracks were built to the many new settlements. By 1889, the population of South Dakota was large enough to warrant statehood.

Ghost Dance of the Sioux

The winter of 1890 found the once-proud Sioux, stripped of much of their lands, living on reservations and participating in the Ghost Dance. This spiritual movement came about in the late 1880s when Native Americans needed something to give them hope. However, the Bureau of Indian Affairs agents were becoming alarmed, claiming that the Lakota had developed a militaristic approach to the dance and began making “ghost shirts” they thought would protect them from bullets. The BIA agent in charge of the Lakota eventually sent the tribal police to arrest Sitting Bull, a leader respected among the Lakotas, to force him to stop the dance. In the following struggle, Sitting Bull and several policemen were killed.

Following the killing of Sitting Bull, the United States sent the Seventh Cavalry to “disarm the Lakota and take control.” During the following events, now known as the Wounded Knee Massacre, on December 29, 1890, 457 U.S. soldiers opened fire upon the Sioux, killing more than 200 of them, including their leader, Chief Big Foot. The massacre at Wounded Knee was the last major clash between American Indians and the U.S. military during the days of the Old West.

Wounded Knee Battlefield, South Dakota, by Kathy Alexander.

Wounded Knee is not within the boundaries of Badlands National Park but is located approximately 45 miles south of the park on Pine Ridge Reservation.

In 1939, the Badlands National Monument was established to protect its fossil resources and stunning geological scenery. The area was re-designated as a National Park in 1978.

In addition to its rich human history and spectacular scenic views, the park today provides numerous hiking trails, ranger programs, a paleontological dig active in the summer, abundant wildlife, campgrounds, and two visitor centers.

The Stronghold Unit, comprised of lands on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, is owned by the Oglala Sioux and managed by the National Park Service under an agreement with the Tribe. This area includes sites of the 1890s Ghost Dances and a Gunnery Range utilized by the United States Air Force during the gunnery range during World War II.

The Badlands National Park is located about one hour east of Rapid City on I-90 at exits 110 and 131