San Antonio-El Paso Road – Legends of America (original) (raw)

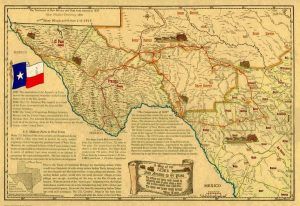

Southwest Texas Road Map, 1850

The San Antonio-El Paso Road, also known as the Lower Emigrant Road or Military Road, was an economically important trade route between the Texas cities of San Antonio and El Paso between 1849 and 1882. The road carried mail, freight, and passengers by horse and wagon across the Edwards Plateau and dangerous Trans-Pecos region of West Texas.

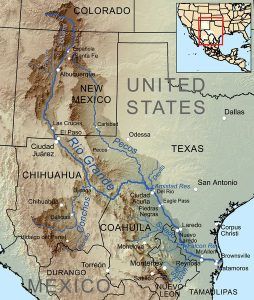

The Republic of Texas was annexed to the United States as the 28th state on December 29, 1845. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed in 1848, established the Texas/Mexico border as the Rio Grande.

The need to survey and develop transportation links between San Antonio, the Gulf Coast, El Paso, and Chihuahua, Mexico became a high priority for the U.S. Army. With the discovery of gold in California the next year, the need for immigrant roads and commercial freighting routes from Texas’ Gulf Coast to El Paso and points west provided additional impetus for the Army to establish and protect routes between Texas’ major cities and the Gulf coast.

During the early years of Texas statehood, the U.S. Army experienced numerous difficulties in establishing and protecting an efficient supply system — particularly for the mobile horse-mounted cavalry. Normally, a cavalry trooper’s horse carried a maximum of 250 pounds, including the rider, limiting supplies normally to 250 rounds of ammunition, a change of clothing, a bed sack, two day’s rations, and one day’s supply of grain. All other equipment and supplies were transported by pack or wagon trains following the expedition. The ordinary two and four-mule escort wagons carried 1,200 to 2,400 pounds of cargo. The largest of wagons, a six-mule jerk-line wagon weighing 1,950 pounds, was capable of carrying from 3,000-3,300 pounds of cargo. In contrast, a single pack mule could carry a maximum of 250 pounds; an average pack-mule train of 50 animals could transport 12,500 pounds of cargo. In short, while wagons could transport greater amounts of supplies using fewer mules, they were generally limited to flat terrain, were slower, and were difficult to hide. For terrains such as the Pecos and Devils River Valleys, pack-mule trains proved to be the most efficient.

John Coffee Hays

In 1848 Colonel John Coffee Hays organized one of the first expeditions from San Antonio to El Paso to determine whether a practicable and convenient route for military and commercial purposes existed. Among the individuals accompanying Colonel Coffee were several Delaware Indian scouts, Richard S. Howard, a San Antonio businessman and ex-Texas Ranger; 35 Texas Rangers under the command of Captain Samuel Highsmith, and several dozen private citizens and businessmen from San Antonio. The group left San Antonio, following the Llano River to its source on the South Fork, and crossed the Divide, arriving at the San Pedro (Devils) River. After spending three days trying to cross it (at a location now submerged under Amistad Reservoir) the Hays Expedition renamed it the Devils River as it is known today. Portions of the modern-day roadbed for Texas Highway 163 from Comstock to Ozona follow the route originally mapped by the Hays Expedition.

On December 10, 1848, the Secretary of War reassigned Brevet Major General William J. Worth to Texas. With the arrival of General Worth, the U.S. Army established a major presence in what had been just a few years earlier the Republic of Texas. Worth was ordered to station troops along the Rio Grande below San Antonio and along the frontier settlements in Texas. He was also directed to examine the country on the left bank (U.S. side) of the Rio Grande and the area west from San Antonio to Santa Fe, New Mexico. In the following year, the U.S. Army made at least seven official reconnaissance trips in western Texas, the Rio Grande Valley, and the gulf coastal plain in an effort to establish reliable routes for the movement of troops as well as for commercial purposes. Most of these expeditions were commanded by officers from the Bureau of Topographical Engineers who carefully mapped the routes of march as well as locations and distances between watering holes, campsites, and major stream crossings.

With Texas firmly in the grip of California’s gold fever, the need for the U.S. Army to establish protected routes from Texas to California became ever more pressing. In January 1849, before the first of the engineering surveys by the Army for the San Antonio-El Paso Road, a party of 25 men, lead by a Mr. Peoples, followed the Hays Expedition route through Val Verde County (and the Amistad Reservoir basin) to became the first group from Texas to reach California. The following month, a group of 32 men calling themselves “The Kinney Rangers” made the trip to California over the same route.

The first of the Bureau of Topographic Engineering ventures was the Whiting-Smith Expedition of 1849. Under the joint leadership of Lieutenant W. H. C. Whiting and Lieutenant William F. Smith, both topographic engineers, the expedition left San Antonio on February 12, 1849, to explore a route of march to El Paso for military and commercial purposes.

With them went a large number of emigrants bound for California. The expedition began along the upper route which followed the San Saba River to its sources, then turned west to the Pecos River and on to El Paso.

At several locations along the San Saba and the Pecos Rivers, the party encountered friendly groups of Lipan Apache. But, west of the Pecos River, they were surrounded by a group of several hundred hostile Apache who eventually allowed them to continue unmolested to the arrival in El Paso on April 12, 1849.

For the return trip, the Whiting-Smith Expedition followed a more southerly route primarily because of a lack of water between the Pecos and San Saba Rivers.

Map of the Rio Grande watershed, showing the Pecos River flowing through eastern New Mexico and west Texas, joining the Rio Grande near Del Rio, Texas. Photo courtesy Wikipedia.

They traveled down the Rio Grande Valley from El Paso for about 100 miles, then turned eastward to the Pecos, down the right bank of the Pecos River Valley for about 60 miles, then on to the Devils River which they followed to within a few miles of its junction at the Rio Grande. This location was not actually the first crossing; rather, it was the first good location with adequate approaches for wagons to cross the river above its confluence with the Rio Grande; the second crossing was at Bakers Crossing 20 miles north of present-day Comstock, Texas. From April 2 – October 25, 1854, the first crossing on the Devils River was protected by Camp Blake under the command of Lieutenant Samuel H. Reynolds and members of Company K, 1st Infantry. Established shortly after the Mexican-American War, Camp Blake was named for Lieutenant J. E. Blake, a topographical engineer, who distinguished himself in the Battle of Palo Alto (the first battle of the Mexican-American War, fought at Palo Alto, Texas, May 8, 1846). There were 18 more crossings of the Devils River above Bakers Crossing before reaching Horsehead Crossing — the last crossing before the San Antonio-El Paso road headed west to El Paso.

Lieutenant Smith felt that the return route was the more practical of the two followed by the expedition and estimated that the existing trail could be widened and made passable for Army freight trains in less than three weeks. At that time, road building consisted of tree and brush clearing, putting logs in creek bottoms and low-water crossings to prevent wagon wheels from bogging down in mud, and the cutting and grading of the approaches to embankments and stream beds. In actuality, much of the proposed lower route up the Devils and Pecos River Valleys coincided with the traditional trails through this wilderness area; thus, what the U.S. Army was proposing to do amounted to upgrading the existing trail to accommodate larger military and commercial freight-hauling wagon trains.

Fort Lancaster Ruins

Lieutenant Whiting noted that security along the lower route could only be maintained through the establishment of a chain of forts at strategic points along the road. This recommendation led to the establishment of Fort Clark in 1852, Fort Davis in the fall of 1854, Fort Lancaster in the summer of 1854, and Camp Hudson in the summer of 1857.

Even with this line of forts, however, it was not until after the Civil War in the 1870s that relatively safe passage was assured along this route. The expedition maps established that water holes were few and far apart west of the Pecos River. In 1853, Jefferson Davis, U. S. Secretary of War, put Captain John Pope in charge of digging water wells in locations where water was 40 miles or more apart. Although some wells were successful, they seldom produced water in sufficient quantities to meet the needs; consequently, the project ended in failure. In March of 1849, the U.S. Army and a group of ordinary citizens from Austin, Texas organized a freight train intent on establishing direct commercial relations with El Paso. The group, under the joint direction of U. S. Army Major Robert S. Neighbors and Doctor John S. Ford, consisted mainly of Austin citizens with commercial interests and a few “friendly Indians.” The friendly American Indians consisted of John Harry, a Delaware Indian; Joe Ellis and Tom Coshatee, Shawnee; Mo-po-cho-co-po and Buffalo Hump, both Comanche Chiefs; and Patrick Gowin, a Choctaw. Striking out westward at the North Bosque near Austin on March 23, 1849, the Neighbors-Ford Expedition reached Horsehead Crossing on the Pecos River on April 17th and arrived in El Paso on May 2nd. Four days later, the expedition began the return journey which traveled eastward back over the Guadalupe Mountains, to Horsehead Crossing on the Pecos River, across the Concho and Brady’s Creek, then on to the San Saba and Llano Rivers, and southeasterly on to San Antonio arriving on June 2nd.

The routes taken to and from El Paso were mapped by the Neighbors-Ford Expedition even though it was not one of the “official” expeditions involving the Bureau of Topographical Engineering. Nonetheless, it was part of the federal government’s larger exploration policy in Texas and therefore should not be interpreted as a purely commercial venture on the part of Austin businessmen attempting to be the first to establish regular commerce with El Paso.

The Neighbors-Ford and the Whiting-Smith Expeditions generally followed the same outbound route all the way to El Paso. The major difference between the two expeditions was their return routes. That of the Neighbors-Ford Expedition soon became known as the “upper road,” while the return route of the Whiting-Smith Expedition became known as the “lower road.” The lower road, from San Felipe Springs (present-day Del Rio) to Horsehead Crossing on the Pecos River, would eventually be known as the Military or Government Road connecting Fort Lancaster, Camp Hudson, the community at San Felipe Springs, Fort Clark, and Fort Inge. To others, the road was known as the lower immigrant road for settlers heading to California from Texas Gulf ports such as Galveston and Indianola. Portions of the route would also become known as the Chihuahua road. Present-day Texas Highway 163 from Comstock to Ozona, Texas, follows sections of the original government road up the Devil’s River Valley to Horsehead Crossing.

Fort Clark Quartermaster’s Building

To test the practicality of the Whiting-Smith Expedition’s recommendation to establish the lower road through Val Verde County (and Amistad Reservoir basin) as the principal route from San Antonio to El Paso, the U.S. Army organized a large freight train to travel the route. Under the command of Brevet Major Jefferson Van Horn, the wagon train departed San Antonio heading due west through the settlements of Castroville, Quihi, and Vandenburg, Texas en route to crossing the Frio River near Sabinal, Texas. At the Frio River, a small train of wagons under the command of Lieutenant Colonel J. E. Johnston and Lieutenant William F. Smith set out in advance of the main group to reconnoiter the general area and make improvements to the existing trail. The main body of the group continued west to the first crossing on the Devils River (now submerged under Lake Amistad), stopping briefly on the Leona River at Fort Inge to pick up additional men and equipment.

By this time, Van Horn’s group included six companies of the Third Infantry, 275 wagons, and 2,500 animals. From a modern perspective, it’s hard to imagine a group this size traveling together through the wilderness canyonlands of Val Verde County and the Amistad Reservoir basin. Van Horn’s group probably stretched out over a mile in length as the wagon train snaked its way up the sinuous Devils River valley and its 18 river crossings before reaching Horsehead Crossing on the Pecos River. Van Horn’s expedition arrived in El Paso, with no major incidents on the trail, on September 8, 1949. The 650-mile trip took exactly 100 days to complete.

Van Horn’s wagon train demonstrated, beyond any shadow of a doubt, that the route was viable and should be relied upon in the future as a major transportation link for the settlement of Texas and the western United States. As the lands along the Rio Grande in New Mexico and the Arizona Territory opened up for U. S. commerce and settlement, the Federal government was laying the foundations for continued expansion ever westward.

President Franklin Pierce wanted to ensure United States possession of the Mesilla Valley in New Mexico near the Rio Grande; at the time, the area was considered to be the most practicable route for a southern transcontinental railway to the Pacific coast. The United States government, therefore, entered into negotiations with Mexico to better define the exact border west of El Paso which had been vaguely defined in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The negotiations concluded in the Gadsden Purchase in 1853 with the United States paying 10 million dollars for about 30,000 square miles of land. The area today forms the southern border of New Mexico and the Arizona border south of the Gila River Valley. The legacy of the San Antonio-El Paso Road is the opening of the American West. From the 1850s to the early 1880s, this road through the Amistad Reservoir basin was a crucial link in the rate at which the west developed. Then, in 1883, everything changed abruptly with the completion of the southern transcontinental railroad. The railway instantly signaled the end of the government’s reliance on wagon trains. Troops, equipment, and messages could move faster, farther, and cheaper by rail and telegraph. Within a few years, the old wagon trail that had helped opened west Texas became used mainly as a thoroughfare for regional traffic. Gone were the mail riders, stagecoaches, and government wagon trains as the steam engine and rail cars replaced the mule and wagon train.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated February 2021.

Also See:

Primary Source: National Park Service