Mountain Meadows Massacre Historical Accounts – Page 21 – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Martha Elizabeth Baker Terry Personal Account, date unknown

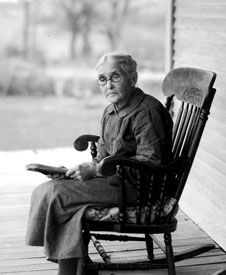

Elizabeth Baker Terry

Six months had passed when we at last camped on the Jordan River in Utah. Our provisions were running low. The cattle were weary and footsore, but we were jubilant. At American Forks, a small settlement, attempts were made to re-provision. The Mormons met our offers with sullen shakes of their heads.

We went through Battle Creek, Provo, Springville, Spanish Fork, Salt Creek, and Fillmore, then we reached Mountain Meadows. Near the lower end the valley tapered to a mere three or four hundred yards, as a gap led out to the scorched sands of the desert beyond. A spring made this section of the meadow a natural camping ground. Here we halted to rest. The day before we were to start was spent in a final check. Every family was on ration. Most of us sought our blankets not long after sundown.

I awoke early, a coffee aroma permeated the wagons which had been drawn up in a helter-skelter fashion. Suddenly there was a rattle of gunfire from the hillside nearest our camp. Whooping savages tumbled down the slope and sliced off our milling stock. The men worked frantically, shoving the heavy schooners and carriages into the form of a huge corral. A few, armed with long rifles, stood on guard. The last wagon was in line when the main band of savages charged down the mountainside yelling and shooting. Rifles began to bark along the train. The attackers hesitated before the viciousness of the fire and fell back. The respite gave us time to dig in. Under Captain Fancher’s direction the wheels of the wagon corral were locked together by means of chains. Others hurried out with picks and shovels and dug feverishly to throw up a breastwork. Even the women helped.

We were on a travel route and it appears that all we have to do was to stand the Indians off until help arrived.

The sun tortured us with intense heat. By midday it was almost unbearable, and we were almost out of water. Later in the day, the last brackish water was consumed.

On the evening of the third day, the Indians made their most determined attack. Crouched low, they circled about the train, shooting inaccurately. The Meadow offered little cover and our assailants felt the lash of the corral sharpshooters. Back they went to the hillsides, carrying their wounded with them. The seige was on again.

The fourth day was the worst of all. The wounded were actually dying of thirst. The entire caravan was weak from lack of water.

The morning of the fifth day dawned. Our resistance was crumbling rapidly. Our ammunition was nearly gone. The stench of our unburied dead was in our nostrils. And always with us was the agony of thirst.

In a twinkling, hope transformed our ranks. We cheered weakly. The horsemen came on at a walk so slowly I thought they would never reach the corral. A square-made man with an air of authority dismounted, smiling at our greetings. He left his companion with the horses. Captain Fancher stepped forward. The stranger took Fancher’s hand. John D. Lee, he said, Indian Commissioner for this district.

Eagerly we crowded about him. He explained gravely that the Paiute Indians were rebellious and difficult to handle, but he believed he could persuade them to parlay. In a lengthy conference between Lee and the men of our band, he gained our complete confidence.

The cry of a sentry shook us from our stupor. Two men mounted on horses and bearing a white flag, were advancing towards us.

When the Indian Commissioner rode off our hope and prayer went with him. He was gone two hours.

He came back at a gallop, a wagon following his dust. He said, they’ve agreed to let you go if you’ll surrender your arms. At first the men objected, then finally agreed to the terms. Slowly they filed to the wagon Lee had brought with him, rifles clattered in the bed.

John D. Lee smiled grimly and and nodded to the driver. The wagon rumbled off over the low rise. Mounting his horse, Lee spurred a short distance from the corral. He rose in his stirrups and shouted, Do your duty.

Bewildered, we stood there. The Indians, shrieking, shooting, and yelling, tumbled down the slopes triumphantly. For a moment the entire wagon train was frozen in immobility.

I started to follow my mother and stumbled. The last I saw of her, she was running toward our carriage with little Billy in her arms. And the Indians were upon us.

Now I could see that they weren’t all Indians. Whites had painted themselves to resemble their savage companions. With bloodcurdling yells they leaped on the defenseless pioneers. I sought shelter under a wagon and peered out between the spokes.

I saw my father fall to the ground.

The Indians and their white companions killed and killed. The sight of blood sent them into a fanatical frenzy. One huge white kept shouting For Jehovah.

The fiends slackened their butchering only when there were no more victims. Dripping paint and blood, they stood panting, searching for any signs of life among the hacked and clubbed bodies.

A white man took me by the hand and led me to a wagon where several other children had been placed. I found my sister, Sarah Frances, there.

As we left, the Indians and whites were completing their looting. Some of the disguised Mormons were washing their paint off at the spring.

Our wagon creaked to the Hamblin ranch a mile away where it discharged its sobbing cargo. We were held at the ranch for several days while the Mormons debated on how to dispose of us.