Seattle, Washington – At the Center of the Klondike Gold Rush – Legends of America (original) (raw)

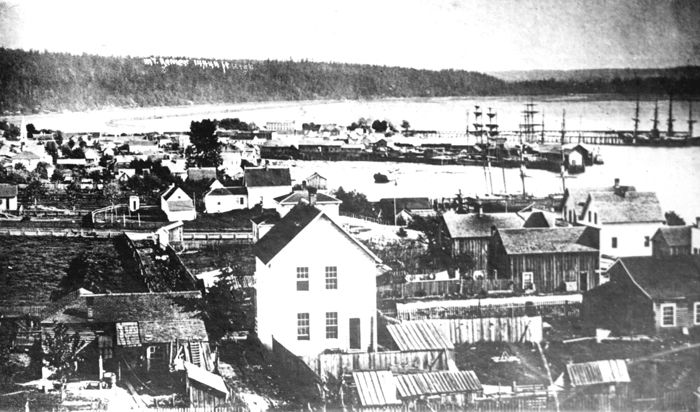

Early Seattle, Washington

In February 1852, a group of settlers founded the city of Seattle, Washington, on the shores of Puget Sound. They chose the location because it provided an excellent place to ship logs and timber south to San Francisco, California. The following year, a steam sawmill was built, and with it, Seattle’s first industry was born.

Duwamish People.

Before Euro-American settlement, the area was inhabited by Native Americans for at least 4,000 years. In May 1792, George Vancouver was the first European to visit the Seattle area during his 1791–1795 expedition for the Royal Navy, which sought to chart the Pacific Northwest for the British. When the area was first explored, the Duwamish had at least 17 villages around Elliot Bay.

Seattle has a history of boom-and-bust cycles, rising and falling several times economically. The first boom, covering the city’s early years, rode on the lumber industry. During this period, the road now known as Yesler Way won the nickname “Skid Road,” supposedly after the timber skidding down the hill to Henry Yesler’s sawmill. The later dereliction of the area may be a possible origin for the term, which later entered the broader American lexicon as Skid Row.

In 1851, a large party of American pioneers led by Luther Collins formally claimed land at the mouth of the Duwamish River on September 14, 1851. Thirteen days later, members of the Collins Party passed three scouts of the Arthur A. Denny Party from Illinois on the way to their claim. Members of the Denny Party claimed land on Alki Point on September 28, 1851. The rest of the Denny Party set sail on the schooner Exact from Portland, Oregon, stopping in Astoria, and landed at Alki Point during a rainstorm on November 13, 1851. After a difficult winter, most of the Denny Party relocated to the eastern shore of Elliott Bay in 1852. It claimed land a second time at the site of present-day Pioneer Square, naming this new settlement Duwamps.

Charles Terry and John Low remained at the original landing location, reestablished their old land claim, and called it “New York,” but renamed “New York Alki” in April 1853, from a Chinook word meaning, roughly, “by and by” or “someday.” For the next few years, New York Alki and Duwamps competed for dominance, but in time, Alki was abandoned, and its residents moved across the bay to join the rest of the settlers.

Chief Seattle.

David Swinson “Doc” Maynard, one of the founders of Duwamps, was the primary advocate for naming the settlement Seattle after Chief Seattle, the chief of the Duwamish and Suquamish tribes.

The name “Seattle” appeared on official Washington Territory papers dated May 23, 1853, when the first plats for the village were filed. In 1855, nominal land settlements were established.

The town grew slowly due to its isolated location and the nation’s involvement in the Civil War.

On January 14, 1865, the Legislature of Territorial Washington incorporated the Town of Seattle with a board of trustees managing the city. The town was disincorporated on January 18, 1867. It remained a mere precinct of King County until late 1869 when a new petition was filed, and the city was re-incorporated on December 2, 1869, with a mayor-council government. That same year, Seattle acquired the nickname “Queen City,” a designation officially changed in 1982 to “Emerald City.”

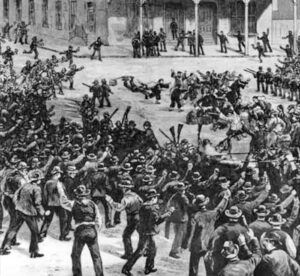

Anti-Chinese riots in Seattle, Washington.

Like much of the U.S. West, Seattle experienced conflicts between labor and management and ethnic tensions that culminated in the anti-Chinese riots of 1885-1886. This violence originated with unemployed whites who were determined to drive the Chinese from Seattle; anti-Chinese riots also occurred in Tacoma, Washington.

Seattle had achieved sufficient economic success when the Great Seattle Fire of 1889 destroyed the central business district. However, a far grander city-center rapidly emerged in its place. For example, the finance company Washington Mutual was founded in the immediate wake of the fire.

In the early 1890s, the Northern Pacific and Great Northern railroads crossed the Cascade Mountain range into Puget Sound. During this period, Seattle began to enjoy economic prosperity as a hub for shipping and railroads.

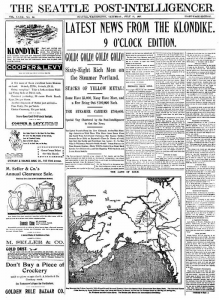

Seattle buzzed with excitement on July 17, 1897, when word came over the telegraph wires two days earlier that the S.S. Portland was heading into Puget Sound from St. Michael, Alaska, with more than a ton of gold in her hold. The gold strike had begun quietly on August 17, 1896, when three miners found gold in the Klondike River, a tributary of the Yukon. News of the strike spread slowly over the next year until miners began to return with their fortunes.

Seattle newspaper announcing the first arrival of gold from Klondike, July 17, 1897

Onboard the Portland were 68 miners and their stores of gold. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper sent reporters on a tugboat to interview the miners before they docked along the Seattle waterfront. Excited by the promise of catching a glimpse of gold, 5,000 people came down to the docks to see the miners and their treasure. The crowd was not disappointed. As the miners descended the gangplank, they hired spectators to help unload their gold. In a matter of hours, Seattle was swept with a case of gold fever. The great Klondike Gold Rush in Yukon Territory was on, as people dropped everything to head for the goldfields.

Seattle’s Pioneer Square, the town’s first settlement area, welcomed thousands of prospective miners, known as “stampeders.” Merchants and ticket agents were beset with stampeders anxious to find transportation to the goldfields and to purchase supplies called “outfits.” Store owners quickly stocked up with goods the prospectors would need and urged them to take advantage of their competitive prices. On average, an outfit for two people costs 250to250 to 250to500, including heavy clothing and boots, nonperishable foods like smoked bacon, beans, rice, and dried fruit, personal items like soap and razor blades, and mining tools. Stampeders had to buy enough supplies to last for several months because there were few opportunities to replenish supplies on the way to the goldfields. By early September, 9,000 people and 3,600 tons of freight had left Seattle for the Klondike.

Vintage Pioneer Square, Seattle, Washington, March 1917.

As they feverishly planned their trip north, Seattle became a temporary home to thousands of people. Steamers taking passengers to Alaska were overbooked and often dangerously overcrowded. Many people who came to Seattle were forced to wait weeks before space became available. Merchants welcomed the flood tide of customers to the city, but hotel rooms and boardinghouses became scarce. Whether arriving by boat or train, newcomers flocked to Pioneer Square to find a bed. Spare rooms, basements, and attics were converted to living quarters for stampeders awaiting transportation to Skagway, Alaska, and other points north.

Pioneer Square offered filling meals and many amusements for those with the time or the money to spare. Hungry stampeders could purchase a meal at one of the many restaurants, cafes, and eateries throughout the business district. Gambling halls, variety theaters, and saloons catered to the whims of many. Adding to the neighborhood’s rough-and-tumble reputation, some dishonest people sold prospectors goods they did not need or substituted poor quality food for the better quality items the stampeders thought they were purchasing.

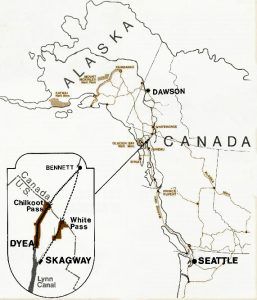

Klondike Gold Rush Map

One of the immediate concerns of the stampeders was the route they would take to the goldfields. Few had any idea of how far they would have to travel after they left Seattle. Many were astonished that the Klondike strike was not in Alaska but across the Canadian border into the Yukon Territory. Since many prospectors were poor, they had to take the less expensive but extremely difficult route up to the Alaskan panhandle and over mountains to the Yukon River and then to Dawson, the town closest to the goldfields. Those who could afford the easier, all-water route traveled to the Yukon River delta and down the river to Dawson City. Most stampeders who set out in the fall would not reach the goldfields until the following spring because the Yukon River had frozen, and the mountain trails from Skagway and Dyea, Alaska, were almost impassable. Most would return to Seattle in a year or two — some with riches, but most poorer than when they started. Others died before ever seeing the goldfields.

Soon after the news of the Klondike gold strike was out, other port cities on the Pacific coast — especially Tacoma, Washington, and Portland, Oregon — were eager to attract the business of stampeders. Erastus Brainerd, hired by Seattle’s Chamber of Commerce to publicize the city’s resources, founded the Bureau of Information to answer questions about outfitting, transportation, and accommodations.

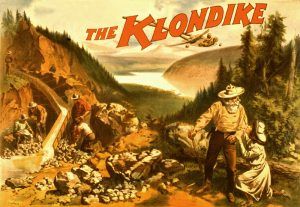

The Klondike Gold Rush by Strobridge & Co., 1897

The Klondike gold strike in the Yukon Territory marked the end of an era when prospectors could hope to dig out a fortune from the earth. Perhaps because it came so late compared to other significant gold strikes, or perhaps because some miners did take home millions despite the frozen environment, this gold rush left a lasting mark on the American imagination. Today, readers still enjoy The Spell of the Yukon by Robert Service and the many works of Jack London, such as Call of the Wild and White Fang, that tell of the immense hardships under which the miners worked. Yet these stories also tell of the far north’s pull on many; even today, they spark readers’ fascination.

The Klondike Gold Rush was significant not only because it was the last great gold rush but also because it increased awareness of the northern frontiers of Alaska and Canada. Unimpressed, the press had labeled the purchase of Alaska as “Seward’s folly” or “Seward’s icebox.” Alaska and the Canadian Northwest, including the Yukon Territory, remained sparsely populated until the end of the century. When the U.S. Census Bureau declared the western frontier closed in 1890, interest in Alaska grew. While millions of acres of empty space in the lower states and territories still existed, more people began to venture north toward the lands they recognized as the last frontier. The discovery of gold, first in Yukon Territory and then in Nome, Alaska, raised the public’s interest in what the far north had to offer.

By the late 19th century, Seattle had become a commercial and shipbuilding center as a gateway to Alaska during the Klondike Gold Rush.

Klondike Miner.

Many changes took place in the Yukon due to the gold rush. A railway was built from Skagway, Alaska, to Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, in 1900. The population of Whitehorse swelled to 30,000 in the same year. The gold-bearing gravel found between the Yukon and Klondike Rivers brought as much as 22millionin1900,butitfellto22 million in 1900, but it fell to 22millionin1900,butitfellto5.6 million by 1910 when most of the prospectors had left for Alaska, returned to Seattle, and set out to other regions.

Many of the stampeders who went through Seattle never reached the goldfields. In fact, between 1897 and 1900, more than 100,000 people from many nations attempted to reach the Klondike, but no more than 40,000 reached Dawson City. Some quit on the trail after experiencing too much hardship. Some returned to their original homes. Still, others returned to Seattle and made it their permanent home. The city had many attractions and rewards for those who decided to stay, but the primary lure was the wealth of jobs for the unemployed. Merchants hired clerks and stockers to keep up with the rising demand for goods and services. Local manufacturers of equipment and clothing, food processors, and shipyards all needed workers. Even the City of Seattle government was hiring because city workers and police officers were needed to replace those who had quit and gone north searching for gold.

For Seattle, the gold rush created a boom that attracted people worldwide even after the gold rush ended. In 1890, Seattle’s population was 42,837. By the turn of the century, that figure had almost doubled, and by 1910, the population had reached 237,194. Matching this growth in population was an expansion of the city boundaries. By annexing small areas to the north and east of Pioneer Square, the size of the city more than doubled by 1910.

Bound for the Klondike Gold Fields, Chilkoot Pass, Alaska

Seattle’s business community continued to flourish. Many miners who returned to Seattle invested their fortunes in local businesses. For example, John Nordstrom invested 13,000ofKlondikegoldintoashoestoreownedbyacobblerhehadmetinthegoldfields.ThatshoestoremarkedthebeginningoftheNordstromdepartmentstorechain.In1907,19−year−oldJamesE.Caseyborrowed13,000 of Klondike gold into a shoe store owned by a cobbler he had met in the goldfields. That shoe store marked the beginning of the Nordstrom department store chain. In 1907, 19-year-old James E. Casey borrowed 13,000ofKlondikegoldintoashoestoreownedbyacobblerhehadmetinthegoldfields.ThatshoestoremarkedthebeginningoftheNordstromdepartmentstorechain.In1907,19−year−oldJamesE.Caseyborrowed100 from a friend and founded the American Messenger Company, which later became UPS. Outfitters, such as Edward Nordoff of Bon Marche, were able to capitalize on their successes during the gold rush and transform their small storefronts into major department stores with branches in many cities.

The Gold Rush era culminated in the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909, which is mainly responsible for the layout of today’s University of Washington campus.

A shipbuilding boom in the early 20th century became massive during World War I, making Seattle somewhat of a company town. The subsequent reduction led to the Seattle General Strike of 1919, an early general strike in the country.

Seattle was mildly prosperous in the 1920s but was particularly hard hit in the Great Depression, experiencing some of the country’s harshest labor strife in that era. However, Seattle was one of the major cities that benefited from President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, such as the Works Progress Administration, CCC, Public Works Administration, and others. The workers, mostly men, built roads, parks, dams, schools, railroads, bridges, docks, and even historical and archival record sites and buildings.

Seattle faced significant unemployment and loss of lumber and construction industries as Los Angeles prevailed as the bigger West Coast city. Seattle had building contracts that rivaled New York City and Chicago but also lost to Los Angeles. Seattle’s eastern farmland faded due to Oregon’s and the Midwest’s, forcing people into town.

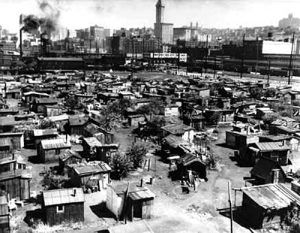

Seattle Hooverville

Hoovervilles arose during the Depression, leading to Seattle’s growing homeless population. Stationed outside Seattle, Hooverville housed thousands of men but few children and no women. With work projects close to the city, Hooverville grew.

A movement of women arose from Seattle during this time, fueled partly by Eleanor Roosevelt’s 1933 book It’s Up to the Women; women pushed for recognition, not just as housewives, but as the backbone of the family. Using newspapers and journals, Working Woman and The Woman Today, women pushed to be seen as equal and receive some recognition.

Violence during the Maritime Strike of 1934 cost Seattle much of its maritime traffic, which was rerouted to the Port of Los Angeles, California.

Seattle’s links with the West Coast and the rest of the country continued to improve its economy. Manufactured goods, timber products, and other natural resources could be shipped by sea to San Francisco, Alaska, and the countries along the Pacific Rim. Goods also could be shipped by rail, with direct connections to Canada, California, the Midwest, and the Northeast. At the dawn of a new century, Seattle had established itself as the premier city of the Northwest.

Boeing Company in World War II.

The city grew after World War II, partly due to the local Boeing company, which established Seattle as a center for aircraft manufacturing. The war dispersed the city’s numerous Japanese-American businessmen due to the Japanese American internment. After the war, however, the local economy dipped. It rose again with Boeing’s growing dominance in the commercial airliner market.

Seattle celebrated its restored prosperity and made a bid for world recognition with the Century 21 Exposition, the 1962 World’s Fair, for which the Space Needle was built.

Another significant local economic downturn was in the late 1960s and early 1970s when Boeing was heavily affected by the oil crises, loss of government contracts, and costs and delays associated with the Boeing 747. Many people left the area to look for work elsewhere, resulting in two local real estate agents putting up a billboard reading, “Will the last person leaving Seattle – Turn out the lights.”

On March 20, 1970, twenty-eight people were killed when an unknown arsonist burned the Ozark Hotel.

Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.

In the 1980s, the Seattle area became a technology center; Microsoft established its headquarters in the region. In 1994, Internet retailer Amazon was founded in Seattle, and Alaska Airlines is based in SeaTac, Washington, serving Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, Seattle’s international airport. The stream of new software, biotechnology, and Internet companies led to an economic revival, which increased the city’s population by almost 50,000 between 1990 and 2000.

Seattle remained the corporate headquarters of Boeing until 2001 when the company separated its headquarters from its major production facilities; the headquarters were moved to Chicago, Illinois. The Seattle area is still home to Boeing’s Renton narrow-body plant and Everett wide-body plant. The company’s credit union for employees, BECU, remains in the Seattle area and has been open to all residents of Washington since 2002.

Wah-Mee Club in Seattle, Washington.

The Wah Mee massacre in 1983 resulted in the killing of 13 people in an illegal gambling club in the Seattle Chinatown-International District. The mass shooting occurred during the night of February 18-19, when three men robbed the club and opened fire. One man who was shot survived to testify against the three in the separate high-profile trials held between 1983 and 1985. It remains the deadliest mass murder in the history of Washington State.

Seattle and its suburbs became home to several technology companies, including Amazon, F5 Networks, RealNetworks, Nintendo of America, and T-Mobile. This success brought an influx of new residents and saw Seattle’s real estate become some of the country’s most expensive.

In 1990, the Goodwill Games were held in the city. Three years later, in 1993, the APEC leaders were hosted in Seattle. That year, the movie Sleepless in Seattle, as did the television sitcom Frasier, brought the city further national attention. The dot-com boom caused a great frenzy among the technology companies in Seattle, but the bubble ended in early 2001.

The Seattle Mardi Gras riot occurred on February 27, 2001, when disturbances broke out in the Pioneer Square neighborhood during Mardi Gras celebrations. There were numerous random attacks on revelers over a period of about three and a half hours. There were also reports of widespread brawling, vandalism, and weapons being brandished. Several women were sexually assaulted. One man, Kris Kime, died of injuries sustained during an attempt to assist a woman being brutalized. About 70 people were reported injured, and damage to local businesses exceeded $100,000.

The very next day, at 10:54:32 local time on February 28, 2001, the Nisqually earthquake occurred, lasting nearly a minute. Although there were no directly related deaths, local news outlets reported that there was one death from a heart attack. About 400 people were injured, much property damage occurred very near the epicenter or in unreinforced concrete or masonry buildings, and power outages affected downtown Seattle.

Amazon Campus in Seattle, Washington.

Another boom began as the city emerged from the Great Recession of 2009, which commenced when Amazon.com moved its headquarters from North Beacon Hill to South Lake Union. This initiated a historic construction boom, which resulted in the completion of almost 10,000 apartments in Seattle in 2017, which was more than any previous year and nearly twice as many as were built in 2016.

Beginning in 2010 and for the next five years, Seattle gained an average of 14,511 residents per year, with the growth strongly skewed toward the city’s center, as unemployment dropped from roughly 9% to 3.6%. The city has found itself “bursting at the seams,” with over 45,000 households spending more than half their income on housing and at least 2,800 people homeless, and with the country’s sixth-worst rush hour traffic.

Today, the seaport city is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2022 population of 749,256, it is the most populous city in the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region of the country. It is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The Seattle metropolitan area’s population is 4.02 million, making it the 15th-largest in the United States. Its growth rate of 21.1% between 2010 and 2020 made it one of the country’s fastest-growing large cities.

Seattle’s culture is heavily defined by its significant musical history. Between 1918 and 1951, nearly 24 jazz nightclubs existed along Jackson Street, from the current Chinatown/International District to the Central District. The jazz scene nurtured the early careers of Ernestine Anderson, Ray Charles, Quincy Jones, and others. In the late 20th and early 21st century, the city also was the origin of several rock bands, including Foo Fighters, Heart, and Jimi Hendrix, and the subgenre of grunge and its pioneering bands, including Alice in Chains, Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and others.