Bill Tilghman – Thirty Years a Lawman – Legends of America (original) (raw)

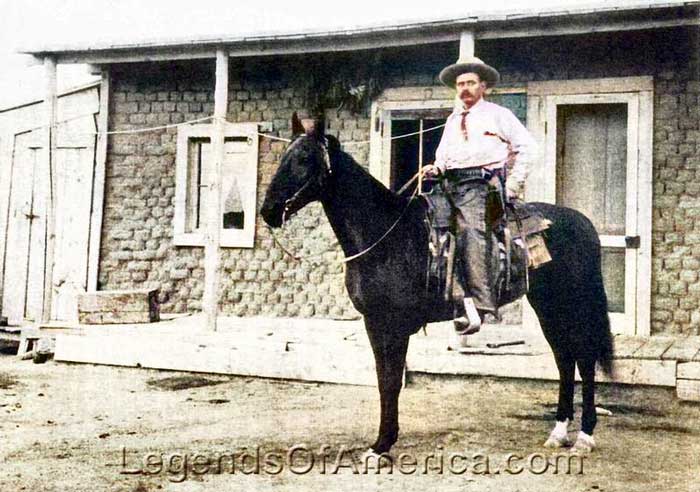

Bill Tilghman on a horse. Touch of color by LOA.

By W.R. (Bat) Masterson in 1907

Notwithstanding the discovery of gold in California in 1849 and at Pike’s Peak, Colorado, ten years later, the civilizing of the West did not commence until after the close of the Civil War. It was during the decade immediately following the ending of the conflict between the North and South that civilization west of the Missouri River first began to assume substantial form.

During this period, three great transcontinental railroad lines were built, starting at some point on the West Bank of the Missouri River. The Union Pacific from Omaha, Nebraska to Ogden, Utah, was completed during these years, the Kansas Pacific Railroad from Kansas City to Denver, Colorado, and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe from Atchison, Kansas, to Pueblo, Colorado.

Twenty years from the day the first railroad tie was laid on the roadbed of the Union Pacific at Omaha, our Western frontier had almost entirely disappeared. There has been no frontier in this country for a good many years. The railroads long ago did away with all there ever was of it. Railroad trains, with their Pullman car and dining-car connections, have reached almost every point in the West of any consequence for the last 20 years.

On what was once known as our great American plains, which a generation ago furnished a habitat for the wild Indian, the buffalo, the deer, and the antelope, today, thousands of beautiful homes can be seen, in which none of the evidence of higher civilization is lacking. While it required only 20 years or so to bring about this great change in this vast territory, the task was by no means easy.

Let the reader remember that in those 20 years, no less than half a dozen bloody Indian wars were fought and that the scenes of those conflicts extended from the Dakotas on the north to the lava beds of Oregon on the west and south to the frontier of Texas; and a pretty good idea of the magnitude of the undertaking will be gained. During those stirring times, nearly all of the famous characters of our once immense frontier, many of whom are now but memories, played a conspicuous part in this vast theatre of human strife.

James B. Hickok (Wild Bill) was perhaps the only one of that chivalrous band of fighting men who composed the vanguard of Western civilization and had acquired fame before the period I named. When this most remarkable man came to the West at the close of the Civil War, in which he had taken a conspicuous part, both in southwest Missouri and in the campaign along the Mississippi River, he brought with him a well-earned reputation for incredible daring and physical courage — a reputation he successfully upheld until stricken down by the assassin Jack McCall at Deadwood, in June 1876. But it was not of Wild Bill I started to write but of one whose daring exploits on the frontier will not suffer by comparison.

Bill Tilghman.

The purpose of this article is to tell the story of Bill Tilghman [_born July 4, 1854_], who was among the first white men to locate a buffalo-hunting camp on the extreme southwestern border of Barber County, Kansas, just across the Indian Reservation line, as far back as 1870. Billy Tilghman is one of the few surviving white men who reached the southwest border of Kansas before the advent of railroads, who is still in harness and, to all intents and purposes, as good both physically and mentally as ever.

It is now 37 years since a slim-built, bright-looking youth, scarcely 17 years old, pulled up for camp one evening on the bank of the Medicine Lodge River in southwestern Kansas, only a few miles north of the boundary line between Kansas and the Indian Territory. An Indian uprising, lasting more than a year, had been put down the previous year by General George Custer. As a natural consequence, the Indians who had participated in the uprising entertained the white man with anything but a friendly feeling.

Like others in that country then, Billy Tilghman became a buffalo hunter and worked along nicely until the Indians got after him. The Indians, by the terms of the treaty lately concluded with the government, had no right to leave their reservation without first obtaining permission from their agent.

It was, therefore, as unlawful for an Indian to be found in Kansas without government permission as it would have been for a white man to enter the Indian Territory for either hunting or trading whiskey with the Indians. The Indians, however, cared little for treaty stipulations at the time and often crossed over into Kansas to pillage and kill buffalo.

The Indian, besides destroying the hunter’s buffalo hides and carrying away his provisions and blankets while he was temporarily away attending to the day’s hunting on the range, was often known to have added murder to his numerous other crimes so that an Indian off his reservation got to be viewed with apprehension by the hunters.

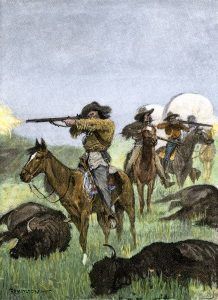

Buffalo Hunting.

It was a well-understood thing among the buffalo hunters whose camps were close to the reservation line that any time a hunter could be taken unawares by the Indians, he was almost sure to be killed, if for no other reason than to secure his gun and belt of cartridges. The Indians had, in prowling around the country one day, come upon Billy Tilghman’s camp and, after pulling up what hides he had staked out on the ground for drying purposes, proceeded to set afire to those already dried and piled up ready for market.

When Tilghman and his two companions returned to camp that evening after their day’s work on the range, they found their camp a complete wreck. Besides destroying several hundred dollars worth of hides, they also found that the noble red men who had visited their camp during their absence had carried off everything to eat. But, as buffalo hunters found no trouble making a hearty meal on buffalo meat alone, they did not despair or go to bed on an empty stomach.

The day’s hunt had taken 25 buffalo hides, and the question of what would be done with them now arose. If they were staked out to dry as the others had been, there was no reason to believe the Indians would not return and destroy them as they had the others. Tilghman’s two partners were moving away first thing in the morning.

“We are liable to all be killed,” said one of them, “if we stay here any longer.”

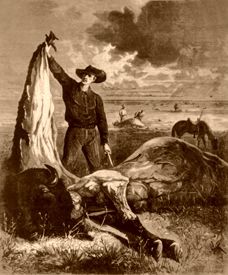

Slaughtered Buffalo, 1874.

“I think we ought to go about twenty miles farther north over on Mule Creek,” said the other. “Besides, the hunting is as good there as it is here. And the Indians hardly ever get that far away from the Reservation.”

“We will move away from here,” said Billy Tilghman in his characteristically deliberate manner, “after I get even with those red thieves for the damage they have done us.”

Although a mere boy at the time, Billy Tilghman was the mastermind of that camp, and what he said was law.

“Ed,” said Billy to one of the partners, “go and hitch up the team and drive to Griffin’s Ranch and get a sack of flour, some coffee and sugar, and a sack of grain for the horses and get back here before daylight in the morning, and Henry and I will unload those hides and peg them out to dry. Don’t forget to feed the team when you get there and let them rest up for an hour or two, as you will have plenty of time to do that and get back here by daybreak.”

Griffin’s Ranch was fifteen miles north of Tilghman’s camp on the Medicine Lodge River and the only place nearer than Wichita, which was one hundred and 50 miles farther east, where hunting supplies and provisions could be obtained.

Ed was soon on his way to Griffin’s Ranch, which only took about three hours to reach. While Tilghman and Henry were busily engaged in fleshing and staking out the green hides, Billy remarked that if those thieving Cheyenne came again around his camp to destroy things. There would likely be a big pow-wow among the Indians as soon as the news of what occurred reached the “for,” said he with some emphasis, “I don’t intend to stop shooting as long as there is one of them in sight.”

“But supposing,” said Henry, “that there is a dozen or so of them when they come, what then?”

“Kill the entire outfit,” replied Billy, “if they don’t run away.”

Little else was said on the subject before bedtime. Still, as Henry later told me, it was not hard to understand from Tilghman’s actions that the only thing that seemed to worry him was the fear that the Indians would fail to pay the camp another visit.

Before daylight the following morning, Ed was back in camp, carrying out his instructions to the letter. After breakfast that morning, Tilghman informed Ed and Henry that they would have to hunt without him that day, as he intended to conceal himself near the camp to be in a position to extend a cordial welcome to the pillaging red-skins when they showed up.

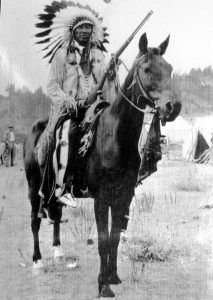

Indians by Charles M. Russell, 1891.

As a precaution, Billy planted himself before the other boys left for the hunting ground so that in case the Indians were watching the camp, they could not tell but what they had all left camp as they had done the previous day. About noon, and just as Billy was commencing to despair, one lone Indian appeared. He rode up very leisurely to the top of a little knoll where he could get a good view of the camp and, after a careful survey of the surroundings and discovering nothing to cause alarm, proceeded to make the usual Indian signals, which is done by circling the pony around in different ways.

Tilghman, crouched down in his little cache, was intently watching the Indian, understanding, as well as the red-skin did, the meaning of the pony’s gyrations. Immediately, six other Indians rode up alongside the first and proceeded to carefully make a mental note of everything in sight.

They soon concluded that there was no lurking danger, and all rode down to the camp and dismounted. This was exactly what Billy had been hoping they would finally conclude to do. Now, if they will only all dismount, said Billy to himself, as he saw the Indians riding down to camp, I will kill the last one in the outfit before they can remount. He got his wish, for they all hopped off as soon as camp was reached. Billy, however, waited for a while to see if they intended mischief before opening up on them with his Sharp’s big fifty buffalo gun that burned 120 grains of powder every time it exploded a shell. He did not have long to wait, for no sooner had one big buck hit the ground than he ran over to the sack of flour, picked it up, and threw it across his pony’s back while some of the others started, as Billy supposed, to cut up the freshly staked hides.

Cheyenne Indian.

The big Indian who had swiped the flour sack had scarcely turned around before Tilghman dropped him in his tracks with his rifle. This, as might be supposed, caused a panic among the other Indians, who little suspected that there was an enemy nearer than the hunting ground until they heard the crack of the gun. Suddenly, Billy had another cartridge, and another thieving Cheyenne was sent to the happy hunting ground. The first Indian that succeeded in reaching his pony had no sooner mounted him than he was knocked off by another bullet from Billy’s big fifty. This made three out of the original seven already killed, and what was unusual for a Southern Plains Indian to do, the remaining four abandoned their ponies. They took it on the run for a nearby clump of timber, which all but one reached safely. Billy managed to nail one more of the fleeing marauders before he could reach the sheltering protection of the woods. The shooting attracted the attention of his partners, who were not more than two miles away, causing them to hurry to camp, where they expected to have to take a hand in a fight with Indians, whom they had reason to believe were responsible for the shooting they had heard.

“The scrap is over,” said Billy when the boys got near enough to hear him, “and three of the hounds have made their escape. I told you last night, didn’t I, Henry, that I would kill all that came if they stood their ground and didn’t run away. Well,” he said, in a rather disconsolate tone of voice, “I fell down somewhat on my calculations, as seven came and I only succeeded in getting four, but then that wasn’t so bad, considering that they left us their ponies.”

“What’s to be done now?” inquired Henry, who was not hankering for a run-in with the Indians then.

“Don’t get frightened.” said Billy, “and remember that we are in Kansas and that those dead Indians were nothing more than thieving outlaws who had no right of their reservation, and if any more of them come around before we are ready to leave, we will start right in killing them.”

Nevertheless, little time was wasted getting away from that locality. The camp dunnage was loaded into the wagon in a hurry, and the team headed towards the north. Ed, who was driving, was told to keep up a lively trot whenever possible. Billy brought up the rear-mounted on one of the Indian ponies and drove the others.

“Look here, Billy,” said Henry, as they were about to pull out of camp, “don’t you think we ought to bury those dead Indians before leaving?”

“Never mind those dead Indians,” replied Tilghman, “the buzzards will attend their funeral; go ahead.”

When dark overtook the party that night, they were on Mule Creek, twenty-five miles from where they had pulled up camp at noon. The Indians reported the occurrence of the killing to their agent at the Cheyenne Agency. Still, they received no satisfaction and were informed that they were liable to be killed every time they left their reservation without permission.

That was Tilghman’s first mix-up with the Indians, but not his last. He continued to hunt in that country, and as the Indians persisted in crossing over into Kansas, there were many clashes between them, which invariably resulted in the Indians getting the worst of the encounter.

A Scout for the Government

During the fall and winter of 1873-4, there was practically no cessation of hostilities between the Indians and hunters along the Indian border, finally culminating in an uprising among the four big southern tribes, namely the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Comanche, which required almost a year for the government to put down. In this Indian war of 1874, Tilghman acted as a scout for the government and, several times while carrying dispatches from one commander to another, had to fight his way out of mighty tight places with the Indians to save himself from being taken alive.

Dodge City, Kansas, about 1875.

After the Indian uprising had been put down, Tilghman went up on the Arkansas River and took up a ranch close to Dodge City, where he lived for several years. In 1884 he was appointed City Marshal of Dodge City and made one of the most efficient marshals the city ever had. He was just the sort of a man to run a town such as Dodge City in those days, being cool-headed, courageous and possessing excellent executive ability.

In the summer of 1888, a County-seat war broke out in one of the northern tiers of counties in Kansas, and Tilghman was sent for by one of the interested parties to come up there and try and straighten the matter out. Tilghman took a young fellow named Ed Prather, whom he had every reason to believe he could rely upon in an emergency. However, Prather proved to be a traitor and attempted to assassinate Tilghman one day, but the latter was too quick for him, and Prather was buried the next day. After straightening out the County-seat trouble, Billy returned to Dodge and continued living there until Oklahoma Territory’s opening fifteen years ago.

He was among the first to reach the territory and took up a claim at Chandler, Lincoln County, where he still resides. When he first went to Oklahoma, Tilghman acted as a U.S. Deputy Marshal and did as much, if not more, to stamp out outlawry in the territory than any other man who ever held office in that country.

The Capture of Bill Doolin

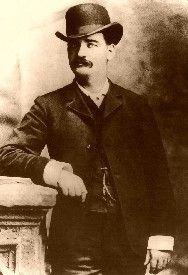

Bill Doolin.

Tilghman has served four years as Sheriff of Lincoln County and killed, captured, and driven a greater number of criminals from the country than any other official in Oklahoma or the Indian Territory. His single-handed capture of Bill Doolin in a bathhouse at Eureka Springs, Arkansas, was perhaps the nerviest act of his official career. Doolin was known to be the most desperate criminal ever domiciled in the Indian Territory and had succeeded for several years in eluding capture. A large reward was offered for his apprehension, and several U.S. Marshals, with their deputies, had several times attempted to arrest him, dead or alive. Still, in every instance, Doolin either eluded them or, when too closely pressed, stood them off with his Winchester.

Doolin was credited with the killing of several Deputy Marshals. Tilghman got after him and trailed him to Eureka Springs, where he found him in a bathhouse. Without calling on the local officials for assistance, he affected his capture single-handedly. Doolin was seated on a lounge in the bathhouse when Tilghman entered, and before the desperado realized what was happening, he was covered by a 45-caliber Colt pistol and ordered to throw up his hands. Doolin hesitated about obeying the order, and Tilghman was forced to walk right up to him and threaten to shoot his head off unless he instantly surrendered. Doolin had his pistol inside his vest and directly under his armpit and made several attempts to get it before he was finally disarmed. It was certainly a daring piece of work by Tilghman, and he was lucky to get away with the job without being killed.

Bill Raidler.

Bill Raidler was another notorious outlaw Tilghman got after, but in this case, the Marshal was forced to kill his man before taking him. Tilghman and Raidler met on the road in the Osage Indian Country, and Tilghman ordered the outlaw to throw up his hands. However, instead of obeying, he opened fire on the Marshal, who instantly poured a fistful of buckshot into the desperado’s breast, killing him in his tracks. Raidler had been a pal of Doolin’s and had been mixed up in several train robberies and had sent word to the U.S. Marshals that if they wanted him to come and get him, but to be sure and come shooting. Tilghman was too good a shot for him at the critical moment, and Bill Raidler’s life paid the penalty for his many crimes. [Most sources say Raidler was injured, tried, and sent to prison – see HERE.]

Thomas Calhoun, a black man, was another notorious outlaw and murderer whom Marshal Marshal Tilghman captured in the Territory, but not until after he had shot and broken the desperado’s leg did he succeed in making him a prisoner. Calhoun was charged with the murder of a colored woman, and a warrant for his arrest was placed in Marshal Tilghman’s hands. The Marshal came upon Calhoun and ordered him to throw up his hands, which he refused to do, and promptly opened fire on Tilghman, who, as he had so often done before, returned it with such good effect that the negro’s leg was broken and he then surrendered but died soon afterward.

Dick West, known as “Little Dick,” was perhaps the worst criminal in the entire territory outside Bill Doolin. “Little Dick” was a member of the Doolin Gang of train robbers and the hardest outlaw in the Territory to trap. He never slept in the house, winter or summer, and kept continually changing about from one place to another. Tilghman finally got track of him and ran him to cover when a fight ensued. Though shot several times, Tilghman escaped without injury and finally succeeded in killing his quarry.

“Little Dick,” like his chief, Bill Doolin, had for several years made a specialty of ambushing and murdering U.S. Deputy Marshals in Oklahoma and the Indian Territory. When the announcement of his death at the hands of Marshal Tilghman was made, there was universal rejoicing among the law-abiding citizens of that country. Space forbids me from going further into the career of William M. Tilghman at this time. It would take a volume the size of an encyclopedia to record this remarkable man’s many daring exploits and adventures. A magazine writer has aptly stated his life’s history as almost a continuation of the memoirs of Davy Crockett or the story of Kit Carson as far as it relates to his adventures on the frontier of Kansas in the early 1870s. After a career covering a period of 37 years, spent mostly on the firing line along civilization’s lurid edge and after being shot at perhaps a hundred different times by the most desperate outlaws in the land, men whose unerring aim with either gun or pistol seldom failed to bring down their victims, this man Tilghman comes through it all without as much as a scratch from a bullet.

Sheriff for More than Thirty Years

Billy Tilghman was born in Iowa in 1854 and moved to Atchison, Kansas, in 1856. as a boy, he passed through the reign of terror known in that country in those days as the Kansas and Border War, which existed for several years along the frontier of those two states. It was a fierce and bitter contest between the pro-slavery influence of Missouri on the one side and the abolitionists of Kansas on the other, which finally culminated in the Civil War.

When Alton B. Parker received the Democratic nomination for the presidency in 1904, Billy Tilghman was selected by the Democratic National Convention as one of the delegates to notify Mr. Parker of his nomination and was last in New York then. He is still a resident of Chandler, Oklahoma, and will, in all probability, be elected Sheriff again this fall. He is perhaps the only frontiersman who has been on the job almost constantly for over a generation and still lives on to tell the story.

By Bat Masterson, 1907. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023. The text as it appears here is not verbatim; it has been edited for the modern reader’s ease.

Personalized Wanted Poster.

Note: Bat Masterson could not have guessed, when he wrote this article in 1907, that Bill Tilghman would die from a bullet. At 70, he was still acting as a lawman when he was appointed as the marshal of Cromwell, Oklahoma. After surviving decades of tough outlaws, he was shot and killed on November 1, 1924, while attempting to arrest a corrupt Prohibition Officer named Wiley Lynn.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

_About the Author and Notes:_Though most of us know that W.B. “Bat” Masterson was famous as a gunfighter and friend of such characters as Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, and Luke Short, many may not know that he was also a writer. After his many escapades in the American West, he accepted the post of U.S. Marshal in New York State. However, by 1891, he was a sports editor for a newspaper in New York City. In 1907 and 1908, he wrote a series of articles for the short-lived Boston magazine Human Life. This tale was just one of several of those articles. Masterson died in 1921 of a heart attack. The article on these pages is not verbatim, as it has been very briefly edited, primarily for spelling and grammatical corrections.

Bat Masterson.

Also See:

Bat Masterson – King of the Gun Players

Complete List of Old West Gunfighters