New Mexico Bad Boy – Clay Allison – Legends of America (original) (raw)

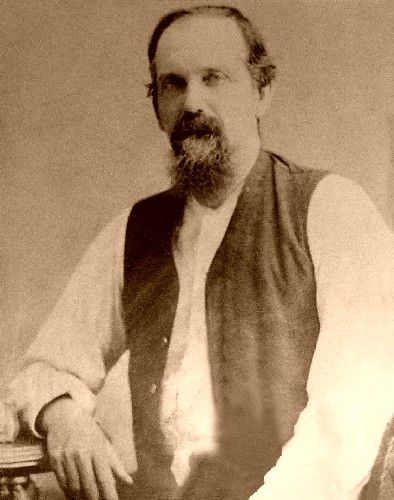

Clay Allison, at age 45.

“His appearance is striking. Tall, straight as an arrow, dark-complexioned, carries himself with ease and grace, gentlemanly and courteous in manner, never betraying by word or action the history of his eventful life.”

— Kinsley Graphic, December 14, 1878.

Robert Andrew “Clay” Allison was once asked what he did for a living, and he replied, “I am a shootist.” It is simply impossible to verify the multiple accounts of his numerous outrageous activities, with “news” being what it was at the time and a century intervening. Though many of the tales were highly exaggerated, if even half were true, people were right to be afraid of him.

Born with a clubfoot, Robert Clay Allison, known as “Clay,” was born September 2, 1840, in Waynesboro, Tennessee, to Jeremiah and Mariah Brown Allison. His father, a Presbyterian minister, also worked in the cattle and sheep business and died when Clay was only five. Clay was said to have been restless from birth, and as he grew into manhood, he became feared for his wild mood swings and easy anger.

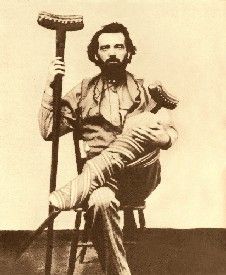

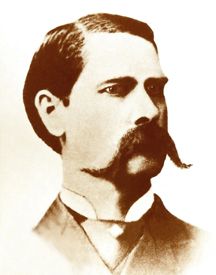

Clay Allison

Clay worked on the family farm until the age of 21 when the Civil War broke out, and he immediately signed up to fight for the Confederacy, enlisting in the Tennessee Light Artillery division on October 15, 1861.

His clubfoot did not seem to hamper his ability to perform active duty. In fact, he was eager to fight, sometimes threatening to kill his superiors because they would not pursue Union troops when they were running away from the battle. However, just a few months later, on January 15, 1862, he received a medical discharge from the service. His discharge papers described the nameless illness as: “Emotional or physical excitement produces paroxysmal of a mixed character, partly epileptic and partly maniacal.” The discharge documents further suggested that the condition might have resulted from “a blow received many years ago, producing a depression of the skull.” That head injury has been the usual explanation for Allison’s psychotic behavior when drinking, perhaps explaining some of his later violent activities.

But, on September 22, 1862, Clay reenlisted in the 9th Tennessee Cavalry and remained with them until the war’s end. He suffered no further medical complications and became a scout and a spy for General Nathan Bedford Forrest. He began sporting the Vandyke beard he wore the rest of his life in imitation of the flamboyant cavalry commander. On May 4, 1865, Allison surrendered with his company at Gainesville, Alabama. He was held as a prisoner of war until May 10, 1865, having been convicted of spying and sentenced to be shot. But the night before he was to face the firing squad, he killed the guard and escaped.

General Nathan Bedford Forrest by Don Troiani

Upon his return to civilian life, Allison became a member of the local Ku Klux Klan, whose dislike for the Freedmen’s Bureau of Wayne County nearly led to armed conflict. Allison was involved in several confrontations before he left Tennessee for Texas. It was said that when a corporal with the Union Third Illinois Cavalry arrived at the family farm, intending to seize the contents of the property, Clay retrieved his gun from the closet and calmly killed the Union soldier.

Allison, his brothers Monroe and John, sister Mary, and her husband, Lewis Coleman, then moved to the Brazos River Country in Texas. Attempting to cross a wide river along the way, Zachary Colbert, the ferryman, presented the price of the crossing. Clay accused the ferryman of overcharging, and an argument ensued, whereby Colbert was left unconscious. This event may have led to the ferryman’s desperado nephew, Chunk Colbert, being killed by Allison some nine years later.

Driving Cattle

Settling down for a while, Clay learned the ways of ranching and became an excellent cowhand in Texas. He signed on with Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving in 1866 and accompanied them on their famous Goodnight-Loving Trail through Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado. Around 1867, Clay worked as a trail boss for M.L. Dalton. He then worked for his brother-in-law, Lewis Coleman, and Irwin W. Lacy, two cattle ranchers who were also legends in their own time.

While in Texas, Allison was said to have had an altercation over the rights of a water hole with a neighbor named Johnson. The two settled the matter by digging a grave and entering the pit with bowie knives. The loser would be buried in the pit, and the winner would gain the rights to the waterhole. Allison had excellent skills with a bowie knife and didn’t lose, but whether or not he killed his neighbor is unknown.

Cimarron River near Springer, New Mexico, by Kathy Alexander.

In 1870, Coleman and Lacy moved to a spread in Colfax County, New Mexico. The Allison brothers accompanied them and, as payment for their work driving the herd, they received 300 head of cattle. Clay took his share and homesteaded a ranch at the junction of the Vermejo and Canadian Rivers, nine miles north of present-day Springer. The two rivers ensured ample water, and Allison built his ranch into a profitable business.

The Allison brothers quickly entered the “social scene in Cimarron and Elizabethtown, and within only a few weeks, the cowboys and ranchers were calling Clay a friend. But the law had not yet come to these early settlements, and the cowboys‘‘ Saturday night visits to town would find them drinking hard, pulling out their six-shooters, and riding up and down the streets yelling and shooting. They made their rounds to the local saloons and gambling halls, where they shot out lamps, lanterns, mirrors, and glasses and were said to have particularly enjoyed making newcomers “dance” as shots were fired at their feet.

Clay Allison

In the fall of 1870, Clay Allison showed the citizens of Elizabethtown how mean and violent his temper was. Charles Kennedy, who was suspected of killing and robbing overnight guests in his isolated cabin on Palo Fletchado Pass, was being held at the Elizabethtown jail. Clay, along with several others, broke into the jail, threw a rope around his neck, and dragged him by a horse up and down Main Street until long after he was dead. Allison then decapitated Kennedy, carrying his head in a sack twenty-nine miles to Cimarron, and demanded that it be staked on a fence at the front of Lambert’s Inn (later the St. James Hotel.)

On April 30, 1871, Allison and two others were said to have stolen 12 government mules belonging to the Fort Union Commander, General Gordon Granger. In the fall, he tried the same stunt again, but when military men came running to the corral, Allison accidentally shot himself in the foot during the confusion. The would-be rustlers escaped to a hideout along the Red River, where Allison sent his friend Davy Crockett (a nephew of the American frontiersman) to fetch Dr. Longwell from Cimarron. Though Clay was treated, he spent the rest of his life with a permanent limp.

After recuperating, Clay was on a drinking spree in a local saloon when suddenly he took a dislike to a man named Wilson. Wilson had the good sense to depart quickly but left Clay in a foul mood. Clay then happened into the County Clerk’s office, where he took offense to something that John Lee, the county clerk, said and slung a knife at him, stapling his sleeve to the timber of a door. Lee broke free and ran across the street to Dr. Longwell’s office.

Vermejo Park Ranch in northeast New Mexico, courtesy Wikipedia

Next, Clay repeated his knife act with a young lawyer, Melvin W. Mills, who also fled to the doctor’s office. Mills described what had happened to the doctor and took up his gun, stating that he would have to kill Allison in self-defense. While the doctor was trying to persuade the lawyer away from such a dangerous act, he noticed that Allison was riding toward the office, at which time the clerk and lawyer promptly fled out of the back door. The doctor exited his office to meet Allison, telling Clay he had been acting badly. The rancher only laughed, stating that he had nothing against Mills or Lee but wanted Wilson’s ear, then rode off in a vain search for Wilson. Mills would carry a grudge against Allison for years, which was later evidenced in the Colfax County War.

Having no fear when it came to other men, Clay was always shy and uncertain when it came to women. But that changed when he met a considerably younger Dora McCullough. When Clay and his brother, John, met Dora and her younger sister, both were smitten. The girls, who were born and raised in Sedalia, Missouri, were orphaned during the Civil War and lived with their guardians, Mr. and Mrs. A.J. Young, on what is now known as the Vermejo Ranch.

Mrs. Young liked John, but Clay’s reputation had preceded him, and she looked upon him with disapproval. Not to be deterred, the two couples eloped in 1873 and, upon their return, begged the forgiveness and blessing of the Young’s. Over time, the Youngs forgave Allison when they observed that Clay never went looking for trouble but didn’t shirk it when it came his way.

After his marriage, Allison met the only man who was able to out-draw him, Mace Bowman. Meeting in Lambert’s Inn one evening, talk turned to Wild Bill Hickok’s fast draw, and Allison stated that he thought he was even faster. Bowman begged to differ and wagered a gallon of whiskey that he could outdraw Allison. In the center of the room, they paced off the distance to the wall and turned. Before Allison was able to get his gun out of the holster, Mace’s six-shooter was pointed at his chest. Allison was amazed and paid Bowman the gallon he owed him. The two took the whiskey to the country, where Bowman taught Allison his lightning-rapid trick.

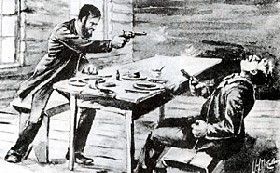

Allison shoots Colbert

On January 7, 1874, Clay killed gunman Chunk Colbert, a known gunslinger. Colbert came to the area looking for a fight with Allison. Some say that Colbert fancied that he could outdraw and outshoot anyone, including Allison. Others say that he wanted revenge for his uncle, Zachary Colbert, the ferryman that Allison had pummeled at the Brazos River nine years earlier. Reportedly, Colbert had already killed six men in Texas and bragged that Allison would be his seventh. Not giving away his motives, Colbert found Allison, and the two spent most of the day together drinking and gambling on horse races.

That night, Colbert invited Allison to dinner at the Clifton House, and Allison accepted. Guessing that there might be trouble, Clay was very cautious, but the talk was friendly as they enjoyed a large meal spread out before them. When they were seated it Colbert laid his gun in his lap, and Allison laid his gun on the table. After the meal was finished, Colbert suddenly reached for his gun under the table and leveled it towards Allison. The perceptive Allison followed suit, and when Colbert’s gun nicked the table, the shot was deflected, and Allison shot him in the head. Later, Allison was asked why He had agreed to have a meal with him and answered, “Because I didn’t want to send a man to hell on an empty stomach.” Colbert was buried in an unmarked grave behind the Clifton House.

Early day Cimarron, New Mexico

Charles Cooper, a friend of the late Mr. Colbert, witnessed the shooting. Less than two weeks after Colbert’s death, Cooper was seen riding with Allison on January 19, 1874. He was never seen again. People started talking, thinking that Allison had killed him, but others thought that Clay simply intimidated the man into leaving. No evidence was ever found to prove the suspicions that Clay had killed the man, but this event would come back to haunt him during the Colfax War.

In the next few years, Clay’s reputation expanded at the same pace as the booming town of Cimarron. The new owners of the Maxwell Land Grant were aggressively exploiting the resources of the grant and were busy with their attempts at evicting the squatters, settlers, farmers, and small ranchers living on the land.

The power behind the grant was a group of politicians and financiers called the “Santa Fe Ring.” Melvin W. Mills, the lawyer that Allison had thrown a knife at several years before, and Dr. Longwell, who had treated Clay’s bullet wound, jumped on the bandwagon and joined the political forces behind the “Ring.” In a bitter 1875 election, Dr. Longwell was made probate judge, while attorney Mills was made a state Legislator.

Clay Allison, 1875

As the burgeoning Cimarron settlement was trying to adjust itself to the influx of prospectors, gamblers, and politics, it found itself in the midst of a great conflict between the land grant company and the settlers of the area. Sheriffs served eviction notices, and retaliation began. Grant pastures were set on fire, cattle rustling increased, and officials were threatened at gunpoint. Grant gang members made nighttime raids of area homes and ranches with threats of violence. The mightily opposed residents formed their own organization, which they called the Colfax County Ring, which some said was led by Clay Allison.

During this time when Cimarron was in need of salvation, Reverend Franklin J. Tolby enlisted with the Methodist Circuit Riders, delivering his sermons in Cimarron, Elizabethtown, Ute Park, Ponil, and Sugarite. Having always had respect for men of the cloth, Clay Allison was one of the first to welcome the minister. Tolby loved Cimarron, planning on making it his home, and quickly sided with the settlers in their opposition against the land grant men. He was very open about his opposition, saying that he would do everything that he could to stop the land grant owners. On September 14, 1875, the 33-year-old minister was found shot in the back in Cimarron Canyon, midway between Elizabethtown and Cimarron, near Clear Creek.

Rumors began to circulate that the new Cimarron Constable, Cruz Vega, was involved in the murder of the Methodist circuit rider. Tolby’s fellow minister and friend, Reverend Oscar Patrick McMains, took up the fight against the “grant men” after Tolby’s murder.

Despite a $3,000 reward for the murderer, no progress was being made on finding Tolby’s killer, and McMains was becoming impatient. The pastor turned to Allison for help, who was more than ready to play judge on horseback.

On the evening of October 30, 1875, a masked mob, who was said to have been led by Clay Allison and Minister McMains, confronted Vega. The constable denied having anything to do with the murder, blaming it on a man by the name of Manuel Cardenas, who had been hired by his uncle, Francisco Griego, and mail contractor Florencio Donaghue. Obviously, the mob did not believe him, and he was pummeled and hanged by the neck of a telegraph pole. Unable to stomach the violence, the Reverend McMains panicked and fled midway through the session.

Possible Vega Grave

After finding Vega’s body later Sunday morning, Francisco “Pancho” Griego, Vega’s uncle, claimed the corpse. On Monday morning, he and a friend transported the boxed remains to the Cimarron cemetery. Suddenly, Clay rode up with his cowboys and informed Griego that Vega was not to be buried in the same cemetery as his victim, Tolby.

Angry but helpless, Griego, along with several mourners, left and began preparing for burial outside the graveyard. Following them, Allison further instructed that Vega was not to be buried inside the city limits. Finally, the remains were placed about a half-mile west of the St. James Hotel.

Later that same day, November 1, 1875, Francisco “Pancho” Griego, along with Cruz’s 18-year-old son and Griego’s partner Florencio Donahue, began making threats to the townspeople in response to Vega’s death. Looking for trouble, they wandered into the St. James Hotel. Allison was in the saloon when Griego accused him of being involved in the hanging of Vega. Griego began fanning himself with his hat in an attempt to distract Allison while he drew his gun. But Allison was not fooled and fired two bullets, killing Griego instantly.

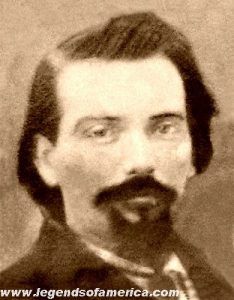

Francisco “Pancho” Griego

The saloon was closed until an inquiry could be held the next morning, and according to local accounts of the day, the saloon closing was the most unfortunate aspect of the whole incident. Allison and his men ran rough-shod over Cimarron all week, spreading general chaos. On Thursday, they were said to have paraded into the local newspaper, brandishing a knife at the editor, and on Friday night, took over Lambert’s Inn, where Allison was said to have stripped naked and performed a war dance over the spot where he had shot Griego, wearing a red ribbon tied around his private parts. On November 10, Allison faced the charges in the killing of Griego, but the charges were dropped when the court ruled the shooting a justifiable homicide.

In the meantime, Manuel Cardenas, the man whom Vega had implicated prior to his death, was arrested and questioned in Elizabethtown. He claimed that Vega had shot the minister, adding that Santa Fe Ringers Mills and Longwell were also behind the killing. When word of this got out, Mills barely escaped a furious lynch mob in Cimarron as he alighted from a coach. Longwell fled in a buggy to Fort Union and safety just ahead of pursuers Clay and his brother John.

However, during his protracted hearing, Cardenas retracted his earlier accusations against Mills and Longwell, stating that he had been coerced at gunpoint, at which time Mills and Longwell were cleared. However, the vigilantes obviously didn’t believe his testimony, and when Cardenas was escorted back to the jail, he was shot to death. Believing that Allison was the head of the vigilantes, this last shooting so enraged the Mexican population of Cimarron that they were determined to have Clay’s scalp. Armed Mexican bands roamed the street, and the atmosphere was so charged that Sheriff Orson K. Chittenden and Deputy Burleson hid Clay for a time at the Chittenden ranch, 20 miles south of Springer. When Allison again began to go about Cimarron, he was said to be a walking arsenal, accompanied by 45 cowboys.

Tolby Grave, Cimarron, New Mexico.

The truth about Tolby’s murder later suggested that the parson, unfortunately, witnessed Griego shooting a man in an argument. When the man later died, Tolby planned to seek an indictment against Griego, who set up Tolby’s murder to silence him. The Santa Fe Ring was dragged into it after Cardenas was “questioned” at gunpoint in Elizabethtown by Joseph Herberger. Evidently, Herberger had been promised a political position by Ringmen Mills and Longwell during the earlier elections earlier in 1875. When the two had failed to follow through, Herberger reportedly forced Cardenas to implicate them. Cardenas later retracted his statement about the Ring men. It was never known who killed Cardenas.

Between the Ring men, the anti-grant vigilantes, and the Mexicans, who had solicited the support of the native Indians, Cimarron was out of control. The Reverend McMains was busy enlisting additional aid from the settlers, telling them that the anger of the Mexicans and Indians was the work of the Grant men, urging them to place themselves at the disposal of Allison. Eventually, guards were posted at all entrances to Cimarron, and no one was allowed to leave town without Allison’s permission. On November 9, 1875, the Santa Fe New Mexican informed the public that Cimarron was in the hands of a mob. Cimarron was actually in the midst of the Colfax County War, which took approximately 200 lives.

Heaping more fuel on the fire, Governor Samuel Beech Axtell, a Santa Fe Ring tool, signed a document on January 14, 1876, that attached Colfax to Taos County. He claimed the change would mean improved law and order. The citizens reacted in fury over the bill, correctly surmising the interference of the Santa Fe Ring.

At about 11 p.m. on January 19, 1876, Allison and two other men, reacting to a scathing editorial where the paper had pointed a finger at Clay Allison as a leader catering to mob violence, broke into the News and Press office and set off a charge of black powder. Then they threw the press into the Cimarron River. Later, he returned to the newspaper office and paid $200 for damages.

Governor Axtell, bothered by Allison’s antics and spurred on by the attorney Mills, was quoted as saying that he “intended to have Allison indicted and punished, or compelled to leave the county.” On February 21, 1876, the governor gave life to a dormant Allison warrant by issuing a $500 reward for Clay, “who is guilty of the crime of murder in killing Charles Cooper,” Chunk Colbert’s friend who had disappeared back in January 1874.

In May or June 1876, as Governor Axtell passed through Cimarron in a stagecoach, Allison climbed aboard and rode with him to Trinidad, Colorado. Clay asked what kind of man it was who had so interfered with his personal freedom. Axtell countered by asking why Allison did not surrender himself on bail and faced his judgment like a man. Clay replied that he had no objection if he could get a fair trial but that he would “never submit to a real trial in Taos County by greasers.” The governor responded that he would demand a fair trial for Allison. Later, Allison turned himself in.

Represented by Charles Springer, the trial was held in Taos. Springer’s main defense was that a body had never been found, and everyone was simply guessing Cooper had been murdered because he had not been seen. Allison was acquitted, and Axtell, true to his promise, declared him a free man.

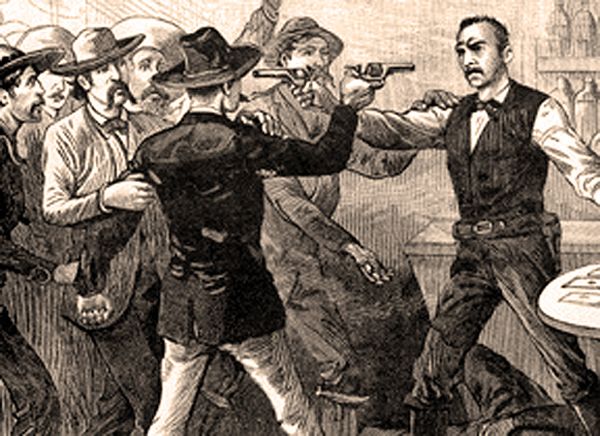

Saloon Gunfight

Clay’s most loyal companion was his brother John, and on December 21, 1876, having just come off the trail, the two decided to have some fun in Las Animas, Colorado. Spotting a local social going on, the two drunk cowboys crashed the party, dancing with some very unwilling partners.

Charles Faber, the deputy sheriff and town marshal, asked the Allison brothers to remove their weapons, but his request went unheard. Faber then left, deputized two local men, and, with a shotgun in hand, led them back into the social. As they came through the door, someone shouted: “Look out!” When John reached for his gun, Faber shot him. Standing at the bar, Clay spun around and fired four shots at Faber, one proving to be fatal. John had already been shot in the chest and arm and was shot yet again in the leg as Faber’s shotgun discharged when he fell. The two deputized men ran from the dance hall, Allison behind them in pursuit, but lucky for them, they escaped.

Clay ran back into the dance hall, calling for a doctor, and slid over to his brother, bringing Faber’s body with him. To John, he said, “Look here! John, this is the s.o.b. that shot you. Everything’s going to be all right. You will be well soon!” Both Clay and John were arrested and charged with manslaughter, but the charges were later dismissed on grounds of self-defense. John recovered from his wounds.

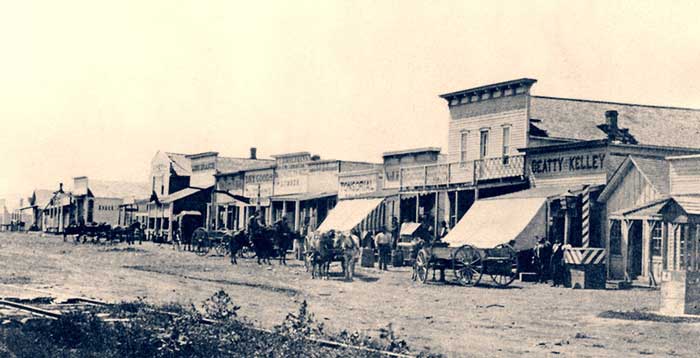

Dodge City, circa 1875

Finally, the restless Clay moved on. On March 3, 1877, he sold his ranch, land, and stock to his brother John for $700. He spent a brief period of time in Sedalia, Missouri, but finally established himself in Hays City, Kansas as a cattle broker.

The numerous stories of Clay Allison’s exploits made him a feared Western legend by the time he arrived in Dodge City, Kansas, in September 1878, several years before Wyatt Earp would become famous. The local newspapers would note his visits to the city, often describing his daring deeds. He was described by the Kinsley [Kansas] Graphic (Kinsley is 36 miles northeast of Dodge City) on December 14, 1878, as: “His appearance is striking. Tall, straight as an arrow, dark-complexioned, carries himself with ease and grace, gentlemanly and courteous in manner, never betraying by word or action the history of his eventful life.”

An often written-about event was the “showdown” between Wyatt Earp, Dodge City Assistant Marshal, and the self-proclaimed “shootist” from New Mexico. According to the stories, Allison planned to protest the treatment of his men by the Dodge City marshals and was willing to back his arguments with gun smoke. In the charged atmosphere of Dodge City, this might have been a very real possibility.

At the time, Dodge City had a reputation for being hard on visiting cattle herders, with stories circulating that cattlemen had been robbed, shot, and beaten over the head with revolvers. Indignant, the cattlemen responded that the marshals were all pimps, gamblers, and saloon keepers.

As a regular practice, Dodge City authorities always disarmed the cowboys when they arrived in Dodge City, however, if one got by and went for a gun, he was immediately shot down by the Dodge City marshals. George Hoyt, who had at one time worked for Clay Allison, had been shot to death while shooting a pistol in the air in the streets of Dodge City.

Wyatt Earp

There are several versions of the story of the showdown. Some say that Allison and his men terrorized Dodge City, while Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson fled in fear. Others, including Wyatt Earp himself, would say that Earp, along with Masterson, pressured Allison into leaving. The most likely version of the account, however, is that Allison was talked into leaving by a saloon keeper and another cattleman, with little or no contact with Wyatt Earp at all. This version, which was later written about by famous Pinkerton Detective Agent Charles Siringo, who was present during the event, is most likely the true story.

Historians basically surmise that Allison might have come to Dodge City looking for trouble, but nothing really happened. While Allison and his men went from saloon to saloon, fortifying themselves with whiskey, Earp and his marshals began to assemble their forces. But in the end, Dick McNulty, owner of a large cattle outfit, and Chalk Beeson, co-owner of the Long Branch Saloon, intervened on behalf of the town, talking the gang into giving up their guns.

By 1880, Clay had moved to a ranch in Hemphill County, Texas, next door to his brother-in-law, Lewis Coleman. On January 17, 1881, it was stated in a local newspaper that “three of the Allison brothers moved on the Gageby.” Though John and Monroe may have joined Clay at some point, they continued using their Colfax County ranch for several years.

While in Texas, Allison’s reputation was kept alive by reports of his unusual antics. Once, he was said to have ridden nude through the streets of Mobeetie, whooping and hollering and declaring that drinks were on him at the local saloon. When the shocked ladies called upon the sheriff to intervene, the officer demanded that Allison get down from his horse. Instead, Allison spurred the steed to full speed up and down the main street, then got off his horse, leveled his gun at the sheriff, and marched him into the bar. He then forced the sheriff to drink until he couldn’t stand up and, satisfied, went back to his horse.

In October 1883, Allison sold his ranch in Hemphill County, and the couple returned to the Seven Rivers region in New Mexico, where Clay continued to ranch. On August 9, 1885, Clay’s first daughter, Pattie Dora, was born in Cimarron.

In the summer of 1886, Clay had just finished a long, hard trail drive that took him to Cheyenne, Wyoming. Having a terrible toothache, he visited a local dentist, who, having already heard of Allison’s reputation, trembled with the thought of who was in his chair. The dentist started working on his tooth, but Clay soon realized that it was the wrong tooth, pushed his way out of the dentist’s chair, and went to find another dentist. After the new dentist pulled the correct tooth, an angry Clay returned to the first dentist, held him down in the dental chair, and pulled one of his molars with a pair of forceps. Attempting to extract a second, the dentist’s screams were heard, and men came and pulled Allison away from the petrified dentist.

Clay Allison Grave, Pecos, Texas

Shortly thereafter, the couple moved again, this time to Pecos, Texas, 50 miles south of the New Mexico line. On July 1, 1887, Allison was hauling a load of supplies to his ranch from Pecos when a sack of grain fell from the wagon. Trying to halt its fall, Clay fell from the heavily loaded wagon, and in the next instant, the wagon wheels rolled across him, breaking his neck. As the horses reared and lurched forward, his neck was further crushed by the heavy buckboard, almost decapitating him.

Unlike most gunfighters of the time, the 47-year-old Allison didn’t die in a blaze of gunfire or at the end of a hangman’s noose but rather stuck under his own wagon forty miles from town. Clay Allison was buried in the Pecos Cemetery the day after his death, where hundreds of people were said to have attended his funeral.

His second daughter, Pearl Clay, was born seven months after his death. Later, Dora married for a second time and moved to Forth Worth, Texas.

Just one month after Clay Allison’s death, his brother Monroe Allison died of a heart attack at his Gageby Creek ranch on August 5, 1887. The 43-year-old bachelor was found next to his horse. John Allison, after a brief and painful illness, died in Clifton, Tennessee, on January 7, 1898, leaving a wife and four daughters. He was not quite 44.

Clay Allison’s life was certainly an adventure, from cattle rustling to lynching to coining the term “shootist.” But his life was also marked by much success as a rancher. Whether Clay Allison was a gentleman or a villain is a question that many have never settled in their own minds.

On August 28, 1975, in a special ceremony, his remains were re-interred in Pecos Park, just west of the Pecos Museum.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

“I have at all times tried to use my influence toward protecting the property holders and substantial men of the country from thieves, outlaws, and murderers, among whom I do not care to be classed.” — Clay Allison, in response to a Missouri newspaper which reported him with 15 killings under his belt.

Also See:

Cimarron – Wild & Baudy Boomtown

Elizabethtown – Gone but Not Forgotten