Frontier Wars – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By Emerson Hough, 1907

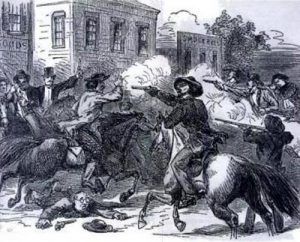

Border War between Missouri and Kansas.

The history of the border wars on the American frontier, where the fighting was more like a battle than murder and where the extent of the crimes against the law became too large for the law ever to undertake any settlement, would make a long series of bloody volumes. These wars of the frontier were sometimes political, as the Kansas anti-slavery warfare; or, again, they were fights over townsites, one armed band against another, and both against the law. Wars over cows, as of the cattlemen against the rustlers and “little fellows,” often took on the phase of large armed bodies of men meeting in a bloody encounter, though the bloodiest of these wars are those least known, and the opera bouffe wars those most widely advertised.

The state of Kansas, now so calm and peaceful, is difficult to picture as the scene of general bloodshed; yet wherever you scratch Kansas history, you find a fight. No territory of equal size has had so much war over many causes. Her story in Indian fighting, gambler fighting, outlaw fighting, townsite fighting, and political fighting is not approached by any other portion of the West. It was bitter and notable if it was sometimes marked with fanaticism or sordidness.

The Sacking of Lawrence, Kansas.

The border wars of Kansas and Missouri immediately preceding the Civil War would be famed in song and story had not the more significant conflict between North and South wiped all that out of memory. Even the North was divided over the great question of the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. Alabama, Arkansas, California, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia gave a whole or a majority vote for this repeal of the Compromise. Against the repeal were Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wisconsin. Illinois and New Jersey voted a tie vote. Ohio cast four votes for the repeal measure and seventeen against it.

This vote brought the territories of Kansas and Nebraska into the Union with the option open on whether or not they should have slavery: “It being the true intent and meaning of this act not to legislate slavery into any territory, nor to exclude it from there, but to leave the people thereof perfectly free to form and regulate their own domestic institutions in their own way.”

That was very well, but who were “the people” of these debated grounds? Hundreds of abolitionists of the North thought it their duty to flock to Kansas and take up arms. Hundreds of the inhabitants of Missouri thought it incumbent upon them to run across the line and vote in Kansas on the “domestic institutions” and to shoot in Kansas and to burn and ravage in Kansas. They were met by the anti-slavery legions along the wide frontier. Brother slew brother for years, one series of more or less sordid and dastardly outrages following another in big or little, murders and arson in big or little, until the whole country, at last, was drawn into this matter of the domestic institutions of “Bleeding Kansas.”

Frontier Homesteaders.

The animosities formed in those days were bitter and enduring, and the more prominent figures on both sides were men marked for later slaughter. The Civil War and the slavery question were fought all over the West for ten years, even 20 years after the war. Some prominent figures emerged from this internecine strife, with many deeds of courage and many romantic adventures. Overall, although the result of all this was for the best and added another state to the list unalterably opposed to human slavery, the story, in detail, is unpleasant and adds no great glory to either side. It is a chapter of American history that is very well written.

When the railroads came across the Western plains, they brought a man who had been present on the American frontier ever since the Revolutionary War, the land boomer. He was in Kentucky in time to rob poor old Daniel Boone of all the lands he thought he owned. He founded Marietta on the Ohio River, on a land steal, and thence, westward, laid out one town after another.

The early settlers who came down the Ohio Valley in the first and second decades of the past century passed the ruins of abandoned towns far back to the east, even in that day. The townsite shark passed across the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers; his record was the same everywhere. In many cases, he was the pioneer of avarice and often inaugurated strife where he purported to establish the law. Each town thought itself the garden spot and center of the universe — one knows not how many Kansas towns, for instance, contended over the absurd honor of being precisely at the center of the United States! — and local pride was such that each citizen must unite with others, even in arms, if need be, to uphold the merits of his own “city.”

This peculiar phase of frontier nature usually came most into evidence over the questions of county seats. Hardly a frontier county seat was ever established without a fight, and often a bloody one. It has chanced that the author has been in and around a few of these clashes between rival towns, and he may say that the intensity of the antagonism of such encounters would have been humorous had it not been so deadly. Two “cities,” composed each of a few frame shanties and a set of blueprint maps, one just as barren of delight as the other, and neither worth fighting over at the time, do not seem typical of any great moral purpose. Yet, at times, their citizens fought as stubbornly as did the men who fought for and against slavery in Kansas. One instance of this sort of thing will do — the Stevens County War, one of the most desperate and bloody, as well as one of the most recent feuds of local politicians.

Cowboys Galloping, by Frederic Remington.

For some reason, perhaps that of the remoteness of time, the wars of the cowmen of the range seem to have had a bolder, less sordid, and more romantic interest if these terms were allowable. When the cowman began to fence up the free-range, to shut up God’s out-of-doors, he entrenched upon more than local or political pride. He was now infringing upon the great principle of personal freedom. He was throttling the West, which had always been a land of freedom. One does not know whether all one’s readers have known it, that indescribable feeling of freedom, of independence, of rebellion at restraint, which came when one could ride or drive for days across the empire of the plains and never meet a fence to hinder, nor need a road to show the way. To meet one of these new far-flung fences of the rich men who began to take up the West was at that time only to cut it and ride on. The free men of the West would not be fenced in. The range was theirs, so they blindly and lovingly thought. Let those blame them who love this day more than that.

But the fence was the sign of the property-owning man, and the property-owning man has consistently beaten the nomad and the restless man at last and set metes and bounds for him to observe. The nesters and rustlers fought out the battle for the free-range more fiercely than was ever generally known.

Wyoming Cattle by Arthur Rothstein.

One of the most widely known of these cow wars was the absurd Johnson County War of Wyoming, which got much newspaper advertising at the time — the summer of 1892 –and was always referred to with a certain contempt among old-timers as the “dude war.” Only two men were killed in this war, and the non-resident cattlemen who undertook to be ultra-Western and do a little vigilante work among the rustlers found that they were not fit for the task. They were happy to get themselves arrested and undercover, especially in protecting the military. They found they had not lost any rustlers when they stirred up a whole valley full and were besieged, surrounded, and almost ready for a general wiping out. They killed a couple of “little fellows,” or some of their hired Texas cowboys did it for them, but that was all they accomplished, except well-nigh to bankrupt Wyoming in the legal chaos, out of which, of course, nothing came. In this party of cattlemen were a member of the legislature, a member of the stock commission, some two dozen wealthy cattlemen, two Harvard graduates, and a young Englishman searching for adventure. They made, on the whole, about the most vile and inefficient band of vigilantes that ever went out to regulate things. However, their deeds were reported by wire to many journals, and for a time, perhaps they felt that they were cutting quite a figure. They had substantial property losses to incite them to their action, for the rustlers were running things in that part of Wyoming, and the local courts would not convict them. This fiasco scarcely hastened the advent of the day— which came soon after the railroads and the farmers — under which the home dweller outweighed the nomad.

Sheepherding in Wyoming by Arthur Rothstein.

Wars between sheepmen and cattlemen sometimes took on the phase of armed bodies of men meeting in a bloody encounter. The sheep were always unwelcome on the range and are so today, although the courts now adjust such matters better than they formerly did. The cow baron and his men often took revenge upon the woolly nuisances themselves and killed them in numbers. The author knows of one instance where five thousand sheep were killed in one box canon by irate cowmen whose range had been invaded. The sheep eat the grass to the point of killing it, and cattle will not feed on a country that sheep have crossed. Many wars of this kind have been known from Montana to Mexico.

Again, factional fights might arise over some trivial matter as an immediate cause in a community or a region where numbers of men relatively equal were separated in self-interest. In a day when life was still wild and free and when the law was still unknown, these differences of opinion sometimes led to bitter and bloody conflicts between factions.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

Go To the Next Chapter – The Lincoln County War

About the Author: Excerpted from The Story of the Outlaw; A Study of the Western Desperado, by Emerson Hough; Outing Publishing Company, New York, 1907. This story is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clerical errors and updated for the modern reader. Emerson Hough (1857–1923) was an author and journalist who wrote factional accounts and historical novels of life in the American West. His works helped establish the Western as a popular genre in literature and motion pictures. For years, Hough wrote the feature “Out-of-Doors” for the Saturday Evening Post and contributed to other major magazines.

Frontier Types.