Kit Carson – The Nestor of the Rocky Mountains – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By Charles Haven Ladd Johnston in 1910

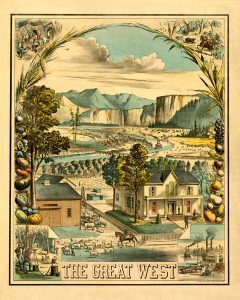

The Great West by Gaylord Watson, 1881.

The expedition led by Lewis and Clark opened the great West to the knowledge of the more adventurous whites. Soon, numerous settlers pressed into the northern section of the country west of the Mississippi River and into the southern portion of the arid plateau and tableland. From Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to Santa Fe, New Mexico, a wagon route was made known as the Santa Fe Trail. The Indians hung along the borders of this rutted way and had many a fierce battle with the whites as they journeyed to and fro in wagons and by pack train.

The great hero of this highway to the southwest was Kit Carson, the Nestor of the Rocky Mountains. Decidedly under the average stature, quick, wiry, with nerves of steel and an indomitable will, such as the great hunter, scout, and man of the plains.

Kit Carson’s youth was similar to that of any boy born upon the frontier whose parents were extremely poor, — he existed and worked. Frequently, there was not enough to eat in the Carson home in Howard County, Missouri, and young Kit would be called upon to assist the meager store of meat by hunting. Thus, he early came to be a good shot and an expert with the rifle, which was fired with a percussion cap and loaded with a ramrod. The repeating rifle was then not manufactured.

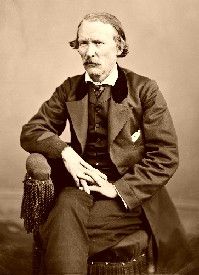

Kit Carson.

When 17 years old, a caravan of traders passed through his little village, bound for the quaint old Spanish-American town of Santa Fe in the far Southwest, and, although apprenticed to a saddler at the time, young Kit could not stand the call of the West. He threw up his position, joined the adventurers, and was soon footing it over the prairie in the wake of the long, lean men with the white-topped wagons and sleek-fed mules. This was in 1826, a time when the greatest interest was taken in the far West, for the people of the United States were restlessly pressing towards the Pacific Coast, having successfully occupied all of the territory east of the broad Mississippi River.

On the Arkansas River in southwestern Colorado was Bent’s Fort, a frontier trading place and refuge for white emigrants, traders, and settlers. Young Kit soon became a hunter here and remained in this occupation for eight years. Forty men were employed at the fort, and it was Carson’s business to supply them with meat from the mountains; an easy task, at times, but, at others, very difficult, for the buffalo, deer, and antelope would migrate with the weather, and would often leave this section almost entirely. The hunter became an unerring shot and was soon well known to the Plains Indians — the Comanche, Arapaho, and Kiowa — while the Ute in the Rockies soon knew him so well that he visited their camps, sat in their lodges, smoked the peace pipe, and dangled their children upon his knee. The Indians liked him so much that they often would listen to his counsel and advice.

Here is a story that illustrates his ability to sway the feelings and actions of the Indians well.

One summer, the Sioux, the most numerous and warlike of the Plains Indians of the north, came far south upon a hunt until they reached the edge of the Arkansas River. The Comanche sent a runner to Bent’s Fort for their friend Kit Carson to aid them in driving the invaders back upon their own soil. The Arapaho had united with the Comanche to assist them in repelling the huntsmen. When Carson rode to meet the southern Indians, he found a vast number of allied braves, furious with anger at the Sioux, and painted and armed for immediate battle.

Tribal Leaders by Edward S. Curtis, about 1900.

“We know that the Sioux have one thousand warriors and many rifles,” said a Comanche chieftain to the well-known scout. “With your assistance, we can overcome them and drive them back into their own hunting grounds. The buffalo are scarce enough. We need them for ourselves and not for the Sioux. Our hearts are now strong. We will teach them not to invade the soil of our fathers.”

“I will go to the Sioux and talk with them,” said Carson. “Leave it to me, my red brothers, and I will use big medicine with the Sioux so that they will go away and will not fight. Leave it to me, and all will be well.”

So saying, he rode unaccompanied to the Sioux, holding up his hand as a token of peace. They received him with no ill will and soon was in counsel with the headmen of this powerful hunting party. He used his best powers of persuasion to avert a clash at arms, and after two days of “big talk,” the Sioux agreed to go north as soon as the buffalo season was over; “for,” said they, “the buffalo have grown very scarce in the northern country. We must have skins for our tepees and meat for the long winter. Hence, we had to come into the country of the Comanche for food as our little children were crying for it.”

The Comanche also agreed to withdraw, and as each side kept to its agreements, the bloody battle was thus averted.

In the spring of 1830, Carson had some daring adventures with the Crow tribe. With four other men, he went to the headwaters of the Arkansas River, where he joined 20 men under Captain John Yount. While in the winter camp, a band of 60 Crow Indians robbed the little band of skin hunters of several horses to recapture, which Kit Carson was dispatched with 15 men. He eagerly took up the trail of the marauders.

It was not hard to track the Indians, and after a day spent in following them, they were found entrenched behind a rude fortification of logs, with the stolen horses tied within ten feet of their shelter. Carson gave his men no time to think what they were doing but cried out, “Charge!” With a wild yell, his men galloped furiously after the trapper, who had started well in advance, and although three of them dropped from Indian bullets, the frontiersmen were soon in among the horses, which they cut loose and carried off with them. Most of the Indians got away, although five fell before the rifles of Carson’s trappers. It had been a stiff, nervy fight.

As the little band of white frontiersmen turned their heads towards Bent’s Fort, someone said, “Boys! We ain’t seed th’ last redskin, by any means. Th’ varmints will be after us, sure, before many days are out, and we’d better hurry along afore too many uv ’em get on our trail.”

Absaroka (Crow) Warriors.

What the old plainsman said was only too true. Before two days had gone, a force of 200 Crow warriors surprised the men under Carson and Captain Yount and did everything they could to capture them. The white men stood them off from behind boulders, trees, and stumps, and as only a few of the Indians had rifles, it was soon apparent that Kit Carson and his party would escape. The plainsmen slowly retreated, keeping up a constant battle with the Indians, and for 50 miles, this fighting went on. Carson was wounded in the leg by an arrow. Several of his friends were killed. Despite this, the little band held together got out into the open country and were soon in the hunting ground of the Comanche, where the Crow were afraid to follow them because of the danger of running into a hostile war party of Indians who were friendly to Carson and unfriendly to them.

This was but one of many thrilling escapes. Not long afterward, while Kit was camped on a tributary to the Green River in Colorado, a young Indian caught six of the best horses belonging to the 25 men who were with the bold and daring trapper, now engaged in capturing beaver and other fur-bearing animals. The theft was soon discovered, and Carson, who had a great reputation as a “thief catcher,” was asked to trace the fugitive and regain the stolen animals. Although the thieving Indian had the start by several hours, Kit galloped after him with enthusiasm, for he wanted to make another capture.

The intrepid scout knew little of this country, so he employed a friendly Ute Indian to assist him in tracking the fugitive. It is hard to realize, but it speaks well for Carson’s persistence when it is known that he pushed after the runaway for 100 miles before they caught up with the thief. It also shows that few Indians were in this country, for none were either seen or met.

Just before the thief was seen, the friendly Indian’s horse gave out so he could go no further. Unwilling to accompany Kit on foot, he returned to the camps of his own people. Carson wasted no time and pressed on alone, determined to catch the thief or kill his own horse in the attempt.

Suddenly, as the plainsman rounded a high hill, he saw the retreating Indian, down below in a valley, leading the stolen horses. The fugitive looked around at this moment and saw his pursuer, so he leaped from his horse, rifle in hand, and ran to a clump of cottonwood trees. Kit saw that the Indian would soon be in a place of concealment, so he determined to take a chance on him as he ran. The distance was three hundred yards. As the thief made for a tree, the keen-eyed plainsman fired, and so perfect had been his aim that the Indian fell forward, stone dead. It was a remarkable shot, for the Indian was on a brisk run, and as Carson was on his horse, his arm was naturally jolted by the movements of his mount.

The six horses were soon caught, tied together by deer thongs, and started for camp, where Carson, the indefatigable thief chaser, arrived after an absence of six days only. So delighted were the leaders of the trappers that the famous plainsman was presented with a large number of peltries, which he subsequently sold at a good profit and invested the proceeds in a new rifle, some better blankets than those he carried, and a few spare horses with which to transport his packs. For a trapper, young Kit was now in prosperous circumstances.

Grizzly bears were plentiful in the country in which Carson was accustomed to setting his traps, and while he was acting as a hunter, not long after his capture of the horse thief, he had an adventure that was both startling and desperate. While camped near the headwaters of a tiny stream where the game was abundant, he killed a large elk within a mile of his camp and, as he leaned over the dead animal to cut its throat, suddenly there appeared, coming towards him, a species of game for which he certainly had not been hunting. It was a large and powerful grizzly bear.

Moved by hunger, the animal apparently wished to make a victim of the frontiersman. He made a lunge toward him, and Kit, having a sudden desire to climb a tree, made all possible use of his limbs to run to a neighboring pine, leaving his gun unloaded and lying beside the animal that he had just killed. The bear did not take the slightest notice of the dead elk and started after the trapper as if man meat was all that he was looking for, while Kit just managed to swing himself upon a limb as the monster’s jaws closed beneath his left foot. Grabbing about for something with which to defend himself, he twisted off a branch from the tree, and with this, he struck the nose of the bear whenever he came uncomfortably near him. The bear was greatly enraged and began to gnaw the body of the tree, but, tiring of this after a while, he began to growl and snarl with great fierceness.

Santa Fe Plaza.

Carson was kept up the tree until nearly midnight. Then, the big grizzly began to walk around the trunk in circles and, in the course of his ramblings, came upon the body of the dead elk. He fell upon this with a will, gorged himself, and then lumbered away into the deep forest. When sure that he was gone, Carson speedily dropped to the ground, and seizing his rifle, he made excellent speed towards his camp, where he was greeted with much joy. Alarmed over his long absence, his comrades intended to soon go in search of their best huntsman and scout.

It was scarcely strange that a man who lived the life that he did would come through without a scratch or a wound of some sort. Soon after the adventure with the big grizzly, Kit went to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and here disposed of his season’s furs at an excellent figure. He had hardly been in this place for a week before another party of 50 trappers set out for the Blackfeet country on the upper Missouri River. The trip was long and tedious, and the band of adventurers soon found themselves in a country that was held by a treacherous and cruel tribe.

Although good watch was kept upon the Indians, one evening a band of Blackfeet stampeded the horses of the white invaders, and stole 18 of the best animals. Carson, who was called the great “thief catcher,” was at once asked to go after the marauders, and, taking 20 of the most lithe and active men in the expedition, he set out after the thieves in a snow storm. The tracks of the Indians were very plain at first, but after a while, they became obliterated, so Kit had to dismount and feel for the print of the fleeing horses with his hands. For 75 miles, the chase was kept up despite all difficulties, and at length, the Indians were sighted.

Instead of stampeding when the whites came in view, the Blackfeet rode towards them, one chief holding up his hand in token of friendship. “Ugh! Ugh!” said the warrior. “We will not fight. We wish to speak with our white brothers.”

“We want our horses,” said Carson. “We wish to have no fight with our red brothers, but if our red brothers will not give up our horses, then there will be one big battle.”

“How,” grunted a chief. “We took the horses because we thought that the animals belonged to the Snake Indians, our enemies. We are your friends. We do not wish to fight.”

But, despite these protestations of friendship, the Indians still refused to give up the animals. Consequently, some of the trappers seized the horses and began to walk them away toward their own outfits. In a moment, the Indians prepared for a fight, and although armed chiefly with bows and arrows, some had rifles that they had obtained at various trading posts.

The Silenced Warwhoop by Charles Schreyvogel, 1908.

Crash! The first rifle spoke in the stillness of the little forest to which the Indians and whites had withdrawn for the conference. A bullet zipped by the head of the Blackfeet leader, dropping an Indian in his rear. Crash Crash! other rifles spat out their slogans of death, and as the arrows hummed through the branches and tree trunks, the trappers took cover. Kit Carson crouched behind a log. Near him were his dearest friend and companion, Markland, a clean man with a clear shot. Opposite them were two dusky warriors, each with a good rifle, and as Kit took aim at his antagonist, he saw another Indian drawing a bead upon his friend, who, totally unconscious of his danger, lay behind a log, busily loading his piece. be spoke that trusty rifle of Kit Carson’s, and the Indian who had a bead upon Markland gave a yelp of pain, rolling over backward with a bullet in his brain. As he fell, Carson, himself, gave a sharp cry, for the second Indian had fired at him, the bullet striking him in the shoulder, shattering the shoulder blade, and making a deep, gaping wound. Although badly hurt, the nervy trapper was not undone, and propping himself against a tree, he loaded again, fired, and the wild, ugly screech that reached his ears bore full witness to the fact that his aim had been true. So the fight waged with fury until night began to throw its shadows over the fray, when the Indians quietly withdrew, still with most of the captured horses. They had won, and the trappers had to mourn the loss of five of their companions.

Upon searching for the wounded, Carson was found lying upon the snow, with his coat gathered into a lump at the shoulder to staunch the terrific flow of blood. He was lifted up on a horse, the bullet was extracted, and the gaping wound was roughly bound up. Thus, supported by two companions, he made the long journey back to camp, for with five killed and four wounded, the trappers did not think it wise to attack again the Blackfeet, who had shown themselves to be quite the equals of the whites in a rough-and-ready fight. They were able to get safely off, and although Captain Bridger took 30 men and started out after the thieving Blackfeet, he could not find their trail.

Kit Carson.

Shortly after this episode, the wounded Kit Carson, having fully recovered, came near losing his life for a second time, but by the hand of a white man and not an Indian. The party of plainsmen had been joined at the Green River, Colorado, by a large number of Frenchmen and Canadians who were employed by the Hudson’s Bay Fur Company, the most powerful of all the companies trading upon the frontier in the United States and Canada. There were now about 100 men in the camp, which was a force thoroughly able to cope with any hostile Indians who might think of attacking them and running off with the livestock.

Among these French adventurers was a braggart and bully by the name of Shuman, a man particularly fond of bad whiskey and of wrestling with, fighting with, and bullying his companions. He was an autocrat and a domineering ne’er-do-well. On one occasion, he began riding around the camp with his gun in his hand, crying: “Zese Americans are a lot of ze chicken-livered scoundrels. What have zey evair done, anyway? Zey come into our rightful trapping ground and catch all of ze beavair which belong to us. Zere’s not a man among ’em. Zere’s not a feller in the whole outfit who isn’t ze cowardly cur. I can lick ten of ’em at once. I’m a regular tornado of fury when I once break loose. Sacre Nom de Dieu!”

Kit Carson, usually very quiet, stood this about as long as he could, then stepped out upon the piece of flat ground, upon which the Frenchman was riding about. “I am an American,” said he, “and I am no coward. You are a vaporing bully, and to show you how Americans can punish liars, I’ll fight you here in any manner, form, or shape that you may desire.”

Shuman drew up with a face fairly purple with rage.

“You cur of an American,” he yelled. “If you are looking for an opportunity to get killed, I have no objection to shooting you as eef you were a dog. Yes, ze dog of an Indian squaw man. Get on your horse, you snip, and we vill ride together after a hundred yards apart. Zen I vill kill you as a mosquito. As a horsefly. Come on, you pale-faced scullion, I vill wipe up ze airth weeth you. Par done. Sapriste! Come on, do not let us delay!”

In a moment, the lithe and agile Kit had mounted his horse, and in a moment, he had galloped off for about 100 yards with his pistol in his hand. The entire camp had rushed out to see the fun, and every trapper there was for Carson, for Shuman was cordially detested by all. Kit wheeled, and the Frenchman raised his rifle to his shoulder. He had trained himself to fire from his running horse by shooting buffaloes, and he felt sure that he could put a bullet clear through the brain of his adversary.

The horses now swept down upon one another, like knights in a tournament in England, until the men were within shooting distance. Shuman raised his rifle and fired. All stood aghast as a lock fell from Carson’s hair, but he still kept on. The smoke from the Frenchman’s gun was just rolling away when Carson put up his pistol and pointed it at the now pale-faced braggart. Crack! A report rang out, and a ball entered Shuman’s hand, plowing upward and lodging in his elbow.

“Eet is enough!” cried the once-proud ruffian. “You could have killed me. I thank you for my life, Monsieur!”

And never afterward did Shuman indulge in bragging talk while in the camp with Kit Carson, the cool-headed.

Carson spent the winter in the Yellowstone River region with only 12 other men. It was a winter of starvation, for game was scarce, and horses had to be slaughtered to supply the little party with meat.

Indian Attack by Frederic Remington, 1907.

When spring came, the huntsmen began to set their steel traps, but, unfortunately for them, their presence was discovered by the thieving, horse-stealing Blackfeet, who, as we have seen, were the very worst enemies that the white men had upon the frontier. One day, the Indians crept upon Carson and five of the party as they were baiting their traps and resetting them. A fierce running fight took place. The Indians were kept in check until the ammunition of the trappers was well-nigh exhausted, and then a retreat was commenced toward camp. The white men were mounted, and during the movement, a horse, upon which one of the trappers had hastily scrambled, stumbled over a fallen log and fell so that the rider was thrown upon his head. He struck a sharp stone and lay unconscious. Five Blackfeet immediately rushed upon the fallen trapper to take his scalp, but the keen eye of Carson had seen the deed, and he leaped to a position near the prostrate and helpless companion. From a tree stump, he shot the foremost Indian and fired so rapidly at the others that they held off to save themselves. Now, seeing that the coast was clear, the plucky Kit dashed to the fallen trapper and pulled him to a place of security behind a large boulder. Here, he soon revived and rejoined his companions after catching his horse.

Not long afterward, the rest of the trappers galloped into view, for they had heard the firing and realized that their compatriots must be in a desperate situation. The battle was now hot, and the crash of rifles waked the echoes of the somber forest. Steadily, the white men drove the yelping Indians back into the woods. As the shadows of night began to fall, the last Indian disappeared over a bluff, shaking his fist vindictively at the trappers but nevertheless running away at no easy gait.

Mountain lions were thick in the section of the country where the trappers found themselves. At night, their weird screams, much like the cry of a strangled child, would sound from the somber recesses of the wildwood. However, as they are great cowards, except when hungry, they would rarely be seen during the day. Nor would they be caught in the traps that were set for them, as they were cunning and suspicious.

One day, Kit was walking along the bank of a stream where many of his traps were set while a companion was behind him preparing supper in the little camp which they had made. Carson had a heavy rifle with him, and seeing a large grouse strutting about in the trail, he raised his piece to shoot off its head when he saw a mountain lion in the upturned roots of a fallen tree. The beast came gradually towards him, and fearing that it would spring upon him, he fired at its forehead just between the eyes. But he missed, and in another instant, the lion was nearby, snarling and hissing like a huge house cat. As he came on, Kit whipped out his sheath knife and struck at the beast, which was apparently hungry and ferocious. Despite his fierce lunges, the animal jumped upon him, ripped his shirt with his sharp claws, and endeavored to bite into his neck with his fangs. The two struggling fighters fell to the ground and rolled over each other down a hillside while the gallant Kit struck again and again at his foe. The lion bit and snarled, but he was no match for the trapper, and after biting him severely in the shoulder, rolled over dead from the deep jabs that Kit had inflicted with his long knife.

Carson now fainted from loss of blood and from his exertions. Thus, he lay for some hours until he was found by his companion, who had tracked him to this spot. He was carried back to camp; his wounds were dressed, and great care was bestowed upon him, for he was dangerously injured. After a month of illness, when he lingered between life and death, he began to recover and, at the end of two months’ time, was able to renew his trapping and hunting. It had been a close shave from death’s door.

Bents Fort, Colorado by Kathy Alexander.

When the famous trapper returned to Bent’s Fort, he fell in love with an Indian girl belonging to the Comanche tribe and married her. Not long after, he became dangerously ill when he was about 100 miles from the fort. When word of his condition was brought to his wife at Bent’s Fort, where she was looking after their small daughter, but two weeks of age. With true devotion, she mounted a horse and immediately started going to the place where her husband lay ill, arriving there in twelve hours. This great exertion brought on a severe fever, and of this, she died in a few days, greatly mourned by the rough, honest Kit Carson, who was devoted to her despite her nationality. The little daughter lived, became a beautiful woman, and subsequently married a merchant in St. Louis, Missouri.

We now come to the most interesting part of the life of this “Monarch of the Plains”: his association with General John C. Fremont in exploring expeditions and in annexing the State of California to the United States of America.

When the well-known trapper was visiting the then frontier post of St. Louis, Missouri, General John C. Fremont was in the city organizing an expedition to explore that part of the country that lay between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains. The general sent for Kit Carson as soon as he learned that the famous plainsman was in town and, after a long interview, employed him as chief guide for his expedition into the land of unfriendly Indians. The expedition party consisted of 21 men, most of whom were part Indian, and another man named Lucien Maxwell of Illinois, who had a big reputation as a hunter. The expedition struck across the broad prairies of Kansas to the Platte River. Then, they traveled by the Oregon Trail past Fort Laramie, Wyoming, to the crags of the Rocky Mountains. The plains were covered with herds of buffalo, and the antelope, in little bunches, grazed contentedly on every side. It was a hunter’s paradise.

As the little party, sunburned, dusty, and weather-stained, rode quietly along the bank of the Platte River, a great herd of buffalo, some 700-800 in number, came crowding up from the river where they had been drinking and began to cross the plain in a leisurely manner, eating as they went. The wind blew from them towards the trappers, so the buffalo could not smell the horses and men. The distance between the party and the herd gave the trappers a splendid opportunity to charge the bison before they could get among the river hills. It was a superb chance for a hunt.

Lucien B. Maxwell

The scouts halted. The hunting horses were brought up and saddled while Kit Carson, Lucien Maxwell, and General Fremont started out together to kill some meat. The buffaloes had grazed to within half a mile, so the three hunters rode easily along until they were within 300 yards of them. All was going well when suddenly an agitation in the herd, wavering to and fro and galloping about of some of the animals on the outskirts, made it apparent that the three plainsmen were discovered. Putting spurs to their horses, the hunters hurried abreast towards the black mass of buffalo, who now wheeled about, snorting with fear, and began to lumber off across the dry plains.

A crowd of bulls brought up the rear of the stampeding mass, and every once in a while, one would face about and then dash on after his companions. Then, he would turn round again and look as if he were half inclined to stay and fight. This did not worry the three plainsmen. When at about 30 yards from the fleeing herd, they all gave a loud yell and rode right into the mass. Many of the bulls, eyeing their pursuers instead of the ground, fell to earth with great force, rolling over and over in the alkali dust, and were soon yellow instead of brown. Each man singled out his particular buffalo and made for it. General Fremont would later write:

“My horse was a trained hunter, famous in the West under the name of Provean, and with his eyes flashing and the foam flying from his mouth, he sprang on after the cow I was pursuing like a hungry tiger. In a few moments, he brought me alongside her and rising in the stirrups; I fired at the distance of a yard, the ball entering at the termination of the long hair and passing near the heart. She fell headlong at the report of the gun, and checking my horse, I looked around for my companions.

At a little distance, Kit Carson was on the ground, engaged in tying his horse to the horns of a cow that he was preparing to cut up. Among the scattered bands, at some distance below, I caught a glimpse of Maxwell, and while I was looking, a light wreath of smoke curled away from his gun, from which I was too far to hear the report. Nearer, and between me and the hill, was the body of the herd, and giving my horse the reins, I dashed after them. A thick cloud of dust hung upon their rear, which filled my mouth and eyes and nearly smothered me. Amidst this, I could see nothing, and the buffaloes were not distinguishable until within thirty feet.

They crowded together more densely still as I approached them. I rushed along in such a compact body that I could not obtain an entrance, the horse almost leaping upon them. In a few moments, the mass divided to the right and left, the horns clattering with noise above everything else, and my horse darted into the opening.

Five or six bulls charged on us as we dashed along the line, but we were left far behind. Singling out a cow, I gave her my fire but struck too high. She gave a tremendous leap and galloped on, swifter than before. I reined up my horse, and the herd swept on like a torrent, leaving the place quiet and clear.

Our chase had led us into dangerous ground, a prairie-dog village so thickly settled that there were three or four holes in every twenty yards square, occupying the whole bottom for nearly two miles in length.”

John C. Fremont by Ehrgott, Forbriger and Co.

Meanwhile, what of Kit Carson? While General Fremont was making his second attack upon the herd, Kit left the buffalo he had killed to pursue a large bull that came running nearby. Leaping upon his well-trained horse, he chased the game for a quarter of a mile, but he could not gain upon the lumbering brute because his horse was very winded. At length, he came up to the side of the fleeing beast and fired, but his horse stepped into a prairie dog hole, fell upon his nose, and threw Kit fully 15 feet over his head. The bullet struck the buffalo near the shoulder but did not inflict a mortal wound. Thoroughly enraged, the infuriated animal pursued the scout who, jumping to his feet with alacrity, made off to the river.

Furious and bleeding from his wound, the buffalo charged after the fleeing trapper. It was a race for life. Never had Carson run as he did now, and the broad waters of the Platte River seemed very far away, indeed. Thud! Thud! came the animal’s heels after the running plainsman, and as Kit leaped from the high bank far out into the clear water, he felt the hot breath of the enraged brute upon his neck. Not stopping to look behind him, he swam way out into the stream, then, turning about, saw the big beast standing upon the bank, shaking his head savagely and stamping vehemently with his forefeet. Kit had won the fastest one-hundred-yard dash on record.

The huntsman swam around for some time, carefully watching his brute enemy, until finally, Trapper Maxwell saw his unfortunate predicament and came to his rescue. With a leaden ball, he shot the big bull through the heart, and then Carson paddled to shore. With a hearty laugh, he crawled to the bank and skinned his ferocious enemy. The wetting did not disconcert him in the least. For the third time in his life, he had escaped a savage foe.

After this successful buffalo hunt, the party pushed on into the unknown West and soon reached Laramie, Wyoming, then a fort and collection of traders’ huts. Sighting the range of spiked mountains nearby, they soon found a way among them and climbed to the top of the highest mountain, which was named Pike’s Peak. Soon after this, Kit Carson left the expedition and went to New Mexico, where, in 1843, he married a Mexican lady, with whom he lived very happily for many years and who gave him two children, a boy, and a girl, only one of whom, the boy, lived to maturity.

In June of this year, he heard that Fremont was organizing another expedition, so he started after him as soon as he learned that he had left Kansas City. When he came up with the explorer, Fremont greeted him effusively, saying, “Carson, you are the man of all others that I am most delighted to see. If I had known your address, I should certainly have communicated my desire to have you accompany me on the present expedition, but since I am so fortunate as to have met you at my camp, I trust your services will be given to me.”

Kit only too joyfully joined the expedition and traveled to the Great Salt Lake in Utah, to the homes of the Digger Indians, and to the Columbia River. The party reached Sutter’s Fort in California as winter approached, the identical place where gold was subsequently discovered for the first time. The men disbanded in the winter, and the adventurous Kit returned to Taos, New Mexico, to engage in sheep ranching. But, in the spring, Fremont projected a third expedition, again calling for the services of the seasoned plainsman. Carson disposed of his sheep ranch at a reckless sacrifice and joined his old commander at Bent’s Fort on the upper Arkansas River. There were 40 men with the daring “Path Finder,” as Fremont was called, and they were all well-seasoned veterans at plains life and fighting Indians.

A lieutenant who was with the party described how Kit Carson prepared for the night. “A braver man,” he says, “than Kit perhaps never lived; in fact, I doubt if he ever knew what fear was, but with all this, he exercised great caution. While arranging his bed, his saddle, which he always used as a pillow, was disposed of in such a manner as to form a barricade for his head; his pistols, half-cocked, were laid above it, and his trusty rifle reposed beneath his blanket by his side, where it was not only ready for instant use but was perfectly protected from the damp. Except now and then to light his pipe, you never caught Kit exposing himself to the full glare of the campfire. He knew too well the treacherous character of the tribes among whom he was now traveling; he had seen men killed at night by a concealed foe who veiled in darkness and stood in perfect security while he shot down the mountaineer clearly seen by the firelight. ‘No, no, boys,’ Kit would say, ‘hang round the fire if you will; it may do for you if you like it, but I don’t want to have a Digger Injun slip an arrow into me when I can’t see him.”‘

Not long after they had started upon this third expedition, as the camp was pitched upon the borders of a little stream near Monterey, California, they were met by General Jose Castro at the head of 400 Mexicans, who opposed the further progress of the Americans and ordered their immediate return. “I refuse to return,” said Fremont. “This country belongs to as much as it does to you. If you want us to leave, you must put us out by force. There are other Americans in Monterey who will join me. I fear neither you nor your men.”

“You will rue this,” said Castro as he withdrew. “I will yet drive you from our country.”

Apache Before the Storm, Edwards S. Curtis, 1906.

The Mexicans, though, in overwhelming numbers, hesitated to attack Fremont, knowing that his small force of 40 men were all veterans. So they stirred up the Apache Indians to war heat and launched these desperate fighters against the invaders of Californian soil.

While Fremont rested at Lawson’s post, word reached him of the approach of 1,000 well-armed Apache, who were determined to put to death every white man in California. “We must leave this post at once,” said Fremont to his men, “for we are in a basin around which are towering hills which, if the enemy once hold, will be of tremendous value to them, for they can shoot down upon us. We must march against the enemy.”

With a cheer, showing their excellent fighting spirit, the men moved out for the attack and proceeded about 50 miles before they discovered the position of the Indians. The horses had not been pushed, as they realized the necessity of having fresh mounts when the Indians should be met with. It was a beautiful clear evening when the scouts rode into the lines, crying: “The Apache are going into camp. They do not know of our whereabouts. We can surprise them and drive them out of the country!”

“We will surround them when they are asleep,” said Fremont. “Let every man fight as he never fought before, for if we do not beat them, it means that none of us shall ever see our friends again.”

At about ten o’clock that night, the Indian camp had been surrounded. At the word of command, the plainsmen put spurs to their horses and galloped down upon the unsuspecting Indians before they were aware of their presence. They were thrown into the greatest confusion, and before they could rally, hundreds of them were shot down as they crawled from their tepees. The Apache were panic-stricken and retreated in the wildest confusion while the invaders ruthlessly cut down all who stood in their path. It was a bloody slaughter, — but no more bloody than the slaughter which these self-same Apache would have administered to them had they awaited their coming and been caught unawares.

This victory taught the Apache a lesson. They no longer listened to the Mexicans’ words. While the remnant of the once-powerful fighting force retreated south, Fremont and his hardy crew departed for Oregon to explore the vast and prosperous country.

“They were,” said a writer:

“a tough-looking crew. A vast cloud of dust appeared first, and thence, in a long file, emerged this wildest war party. Fremont rode ahead, a spare, active-looking man with such an eye! He was dressed in a blouse and leggins and wore a felt hat. After him came five Delaware Indians, who were his bodyguards and had been with him through all his wanderings. They were his bodyguards and had charge of the two baggage horses.

“The rest, many of them blacker than the Indians, rode two and two, the rifle held in one hand across the saddle’s pommel. Thirty-nine of them are his regular men; the rest are loafers whom he has lately picked up. His original men are principally the woodsmen from the State of Tennessee and the banks of the upper waters of the Missouri River. The dress of these was principally a long, loose coat of deerskin, tied with thongs in front; trousers of the same of their own manufacture, which, when wet through, they take off, scrape well inside with a knife, and put on as soon as dry. The saddles were of various fashions, though these, and a large drove of horses and a brass field gun were things they had picked up around California. They are allowed no liquor — tea and sugar only. This, no doubt, has much to do with their good conduct, and the discipline, too, is very strict.”

There were numerous skirmishes with the hostile Indians, and when the explorers returned to Lawson’s post, they found that the Mexicans were again prepared to dispute their advance. At Sonoma, California, was a strong garrison, but this fort was attacked and carried. All the Americans in the district now rallied to Fremont’s standard. They marched against 800 Mexicans sent out by General Castro from San Francisco, crying, “We will exterminate every American in California.” Instead of this, they retreated as soon as Fremont and his men approached and were pursued for six days before they hurriedly disbanded. Detachments from a fleet of United States cruisers now aided the victorious Fremont in an attack upon Monterey, and a flag was adopted, composed of red and white bunting with the figure of a bear in the center. The independence of California was declared, and the “Bear Flag” became the emblem of its nationality.

California was now practically free from Mexican rule — thanks to Fremont, Kit Carson, and their small force of adventurous plainsmen. Other American troops arrived on the scene under General Kearney and, taking possession of the fort at Los Angeles, practically closed the hostilities between the Mexicans and the wild band of original rough riders. Forty men had made the first blow, which struck the shackles of Mexican dominion from the fair soil of California, the Golden State. And Carson had not been the least of these.

Kit Carson House, Rayado, New Mexico, in the 1940s.

Kit Carson returned to New Mexico. On his way back, he passed the Little Salt Lake, near the Wahsatch Mountains, whose summits were covered with many feet of snow. In crossing a deep gorge, suddenly, he and his party stumbled upon the remains of ten human beings whose bones lay bleaching in the bright rays of the sun. Hungry wolves had gnawed and torn them so that they were widely scattered. “These are the relics of some unfortunate party of whites that the Indians have cut off,” said Carson sadly. “One of these lying apart from the rest, from the bullets and arrowheads in the tree nearby, must have belonged to one of the parties who fought from this shelter until overcome by the enemy.”

It was subsequently learned that these bones belonged to a body of emigrants from Arkansas who had been surprised by hostile Indians while resting to eat their lunch. All were immediately killed except one, who snatched up his rifle and retreated to the nearest cover. There, he put up a despairing battle, slaying several of his attackers, before the arrows of the murderous Indians dispatched him.

The rest of Kit Carson’s life was spent ranching and fighting Indians, a business in which he was now adept. However, one little fight of his deserves special mention.

Some Apache warriors raided the settlements near the home of the famous scout and, after murdering several of the settlers, made off into the mountains. Carson started in pursuit with a band of revengeful white men and tracked them to a strong position in the foothills. So eager was old Kit to avenge the slaughter of his friends that he gave a wild shout and dashed after them, expecting, of course, to be reinforced by his companions. But, as he galloped towards the Indians, his friends fell back, and he suddenly found himself alone among the marauders.

One of Carson’s great characteristics was his absolute coolness in times of danger. As the Indians, with a wild, ear-splitting yelp of hatred, debouched from their hiding place and galloped around him, in a second, he threw himself upon the offside of his horse and rode back towards his party. Fortunately for him, the Apache had only arrows. Six stuck into Kit’s trusty horse as he beat this wild retreat, and a bullet passed through his coat tail. But, he came off scott-free and was soon laughing and smiling with his companions as the Indians were forced to withdraw from a well-aimed volley of the whites. The Apache scattered and escaped into the wild passes of the bleak and barren mountains.

Such was his reputation in fighting these scourges of the settlements that, in 1862, the gallant Kit was entrusted with an important command against some of the thieving and murdering tribes of New Mexico and Arizona. He brought the Mescaleros to terms. He made such a spirited attack upon the Navajo that they finally unconditionally surrendered and were placed on a government reservation. Near the Canadian River in Texas, he attacked a Kiowa village of about 150 lodges and signally defeated this strong and powerful tribe. “This brilliant affair,” said his commanding officer, “adds another leaf to the laurel wreath which you have so nobly won in the service of your country.” And with all this praise, sturdy old Kit — now a general — was as modest as a child. Such was his power among the Indians that he was appointed an Indian Agent, a post which he filled with the greatest satisfaction to the United States Government.

All men must grow old. The wiry and indefatigable scout, ranchman, Indian fighter, and soldier began to show signs of the hard life which he had led upon the plains. Despite his years, in January 1868, he was called to Washington to give evidence and advice in a dispute between the Government and the Apache. A number of these fierce warriors accompanied him.

The famous plainsman’s journey to the East was a great triumphal tour. Everywhere along the route, flags were raised, and cities were decorated with flowers and bunting in token of the great admiration felt for the aged pioneer and Indian fighter. For he embodied characteristics that all admire—goodness, good sense, honesty, and courage.

In March, the great pioneer returned to New Mexico, well pleased and gratified with the honors that his grateful countrymen had showered upon him. But the Angel of Death hovered over the once vigorous frame of the mighty pioneer. On May 23, 1868, while visiting his son at Fort Lyons, Colorado, and when in the act of mounting a horse, an artery in his neck was ruptured, and in a few moments, the soul of the aged plainsman had gone to the great beyond.

So, remember the famous mountaineer, trapper, guide, pioneer, and Indian counselor. As a frontiersman, he had no superior. His reputation was never tainted with any moral stain; he was neither a murderer or a man who engaged in frontier brawls. The times bred men of courage, and he was one of these. The wild country needed men of a clear head and undaunted nerve to advance its civilization, and it found its pathmaker in a brave Indian fighter and man of the plains. He lived his wildlife and lived it well. No man could have done better than he — the Nestor of the Rocky Mountains!

By Charles Haven Ladd Johnston, 1910. Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

About the Article: This article, written by Charles Haven Ladd Johnston, was excerpted from his book Famous Scouts, Including Trappers, Pioneers, and Soldiers of the Frontier …, published in 1910 and now in the public domain. Charles Johnston was a prolific writer of history and published numerous books about the history of the Old West, as well as world history. The text that appears on these pages is not verbatim, as corrections have been made to erroneous information, and the article has been heavily edited for the modern reader.