The Overland Mail – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By Frederick Ritchie Bechdolt in 1922

Trapper’s Last Shot by T.D. Booth.

From the time when the first lean and bearded horsemen in their garments of fringed buckskin rode out into the savage West, men gave the same excuse for traveling that hard road toward the setting sun.

The early pathfinders maintained there must be all manner of high-priced furs beyond the skyline. The emigrants who followed in the days of ’49 informed their neighbors that they would gather golden nuggets in California. The teamsters who drove the heavy freight wagons over the new trails a few years later told their relatives and friends that they were going West to better their fortunes. And, when the Concord coaches came to carry the mail between the frontier settlements and San Francisco, the men of wealth who financed the different lines announced there was big money in the ventures; the men of action who operated them claimed that high wages brought them into it.

So now you see them all: pathfinder, Argonaut, teamster, stage driver, Pony Express rider, and capitalist, easing their consciences and soothing away the trepidations of their women-folk with the good old American excuse that they were going to make money.

That excuse was only an excuse and nothing more. In their inmost hearts, all these men knew that they had other motives.

One individual did not try to hoodwink himself or others about this Western business. This man, as well as many of the others, had an itching that was troubling all the rest of them. That individual asserted loudly and with lamentations that the spirit of adventure was blazing within him; he wanted to go out West to fight Indians and desperadoes. He was hot with the lust for adventure. The men of action wanted to risk their lives, and the men of wealth wanted to risk their dollars. This does not imply that the latter element was anxious to lose those dollars any more than it implies that the former expected to lose their lives. But, both were eager for the hazard.

All of them dreamed dreams and saw visions. And the dreams were realized; the visions became actualities. Few of them justified their excuse of money-making; many came out of the adventure poorer in this world’s goods than when they went into it. But, every man had the time of his life and lived out his days with a wealth of memories more precious than gold, memories of a man’s part in a great rough drama.

The Winning of the West, that drama has been called. Perhaps no act in the play attained the heights that the last one reached before the coming of the railroad, the one with which this story has to deal, wherein bold men allied themselves on different sides to get the contract of carrying the mail by stage coaches on schedule time across the wilderness.

Initially, the frontier was about 200 miles west of the Mississippi River. Behind that frontier wide-stacked wood-burning locomotives were drawing long trains on tracks of steel; steamers came sighing up and down the muddy rivers; cities smeared the sky with clouds of coal smoke; under those sooty palls, men in high hats and women in enormous hoop-skirts passed in afternoon promenade down the sidewalks; newspapers displayed the day’s tidings in black headlines; the telegraph flashed messages from one end of that land to the other; and where the sharp church steeple of the most remote village cut the sky, the people read and thought and talked the same things which were being discussed in Delmonico at the same hour.

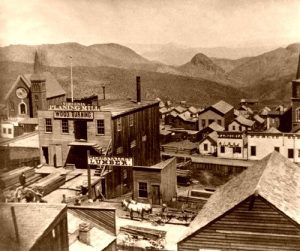

San Francisco, 1849.

Beyond the Sierra Nevadas, there was another civilization. In San Francisco, in hotel lobbies, men and women passed and re-passed one another dressed in Eastern fashions — some months late, but Eastern fashions nonetheless. Newspapers proclaimed the latest tidings from the East in large type. Men were falling out over the same political issues embroiled them by the Atlantic seaboard and embarking on the same sort of business ventures.

But 2,000 miles of wilderness separated these two portions of the nation. Bands of hostile Indians made traversing that vast expanse of prairies as level as the sea, sagebrush plains, snow-capped mountains, and silent, deadly deserts more difficult.

The Great West by Gaylord Watson, 1881.

In Europe, such an interval would have remained for centuries, spanned by the slow migration of those driven by ill fortune and bad government from the more crowded communities on each side. During that time, these two civilizations would have continued in their own ways, developing their own distinct customs until, in the end, they would have become separate countries.

But, the people east of the Mississippi River and the people west of the Sierras were Americans, and the desire for a close union was strong. Their business habits were such that they could not carry on commercial affairs without it. Their political beliefs and their social tendencies kept them chafing for it. Furthermore, their characteristic was not to acknowledge nature’s obstacles as permanent. Two thousand miles of wild prairie, mountain ranges, and deserts meant a task, the more blithely to be undertaken because it was made hazardous by the presence of hostile Indians.

So now the East began to cry to the West and the West to the East, each voicing a desire for quicker communication. Getting letters from New York to San Francisco in a timely manner became one of the problems of the day.

The first step toward a solution was the choice of a route, and while this was up to Washington, the proof on which it rested was up to the men of wealth and the men of action. Immediately, two rival groups began striving, each to prove that its route was the quickest. Russell, Majors & Waddell, who held large freighting contracts on the northern road from Independence, Missouri, via Salt Lake City to Sacramento, California, bent their energies to demonstrating its practicability; the Wells-Butterfield stage and expressmen undertook to show that the more extended pathway from St. Louis by way of the Southwestern territories to San Francisco was best.

In 1855, Senator W. M. Gwin of California, who had conceived the idea with F. B. Ficklin, general superintendent of the Russell, Majors & Waddell Co., introduced a bill in Congress for bringing the mails by horseback on the northern route, but the measure was pigeonholed. Snow in the mountains was the main argument against it.

Street in El Paso, Texas, 1888.

In 1857, James E. Birch got the contract for carrying semi-monthly mail from San Antonio, Texas, to San Diego, California, and the southern route’s champions had the opportunity to prove their contention.

Save for a few brief stretches in Texas and Arizona, there was no wagon road, and El Paso and Tucson were the only towns between them. A few far-flung military outposts, whose troops of dragoons were having a hard time holding their own against the Comanche and Apache, afforded the only semblance of protection from the Indians.

Horsemen carried the first mail-sacks across this wilderness of dark mountains and flaming deserts. On that initial trip, Silas St. Johns and Charles Mason rode side by side over the stretch from Carrizo Creek in Texas to Jaeger’s Ferry, where Yuma, Arizona, stands today. That ride took them straight through the Imperial Valley. The waters of the Colorado River, which have made the region famous for its rich crops, had not been diverted in those days. The hottest desert in North America was sandhills, blinding alkali flats, and only one tepid spring in the distance. One hundred and ten miles, and the two horsemen made it in 32 hours.

The company has now begun to prepare the way for stagecoaches. During the latter part of November, St. Johns and two companions drove a herd of stock from Jaeger’s Ferry to Maricopa Wells. The latter point had been selected for a relay station because of the water and the presence of the friendly Pima and Maricopa Indians, who kept the Apache at a distance. During that drive of about 200 miles, the pack mule lost his load one night in the desert. The men went without food for three days and, for 36 hours, traveled without a drop of water in their canteens.

Fort Davis, Texas Parade Ground.

The first stage left San Diego for the East in December with six passengers. Throughout the trip, a hostler rode behind herding a relay team. The driver kept his six horses to their utmost for two hours; stock and wearied passengers were given a two-hour rest, after which the fresh team was hooked up, and the journey resumed.

In this manner, they made about 50 miles a day. When they arrived at Fort Davis, Texas, they found the garrison, whom they had expected to supply them with provisions short of food, and they subsisted for the next five days on what barley they felt justified in taking away from the horses. They arrived at Fort Lancaster, Texas, just after the departure of a Comanche war party who had stolen all the stock and were obliged to go 200 miles further before they could get a relay. But, these incidents and a delay or two because of swollen rivers accounted for only minor mishaps. They came through with their scalps and the mail sacks — only ten days behind schedule.

After that, the Birch line continued its service, and letters came from San Francisco to St. Louis, Missouri, in about six weeks. Occasionally, Indians massacred a party of travelers; now and then, renegade whites or Mexicans robbed the passengers of their belongings and looted the mail-sacks. But, such things were no more than anyone expected. James Birch had proved his point. The southern route was practical, and in 1858, the government let a six-year contract for carrying letters twice a week between St. Louis and San Francisco to John Butterfield of Utica, New York.

Thus, the Wells-Butterfield interests scored the first decisive victory. Butterfield’s compensation was fixed at $600,000 a year, and the schedule was 25 days. The route went through Fort Smith, Arkansas; El Paso, Texas; and Tucson and Jaeger’s Ferry in Arizona, over a length of 2,760 miles. Of this, nearly 2,000 were in hostile Indian country.

To travel this distance in 25 days meant a fast clip for horses and a lumbering Concord coach over ungraded roads. Such a clip necessitated frequent relays, which, in turn, demanded stations at short intervals. While a road gang was removing the ugliest barriers in various mountain passes, another party went along the line erecting adobe houses. These houses were little forts, well suited for withstanding the attacks of hostile Indians. The corrals beside them were walled like ancient castle-yards.

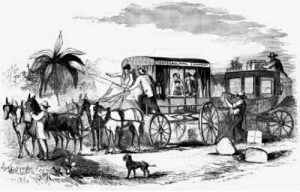

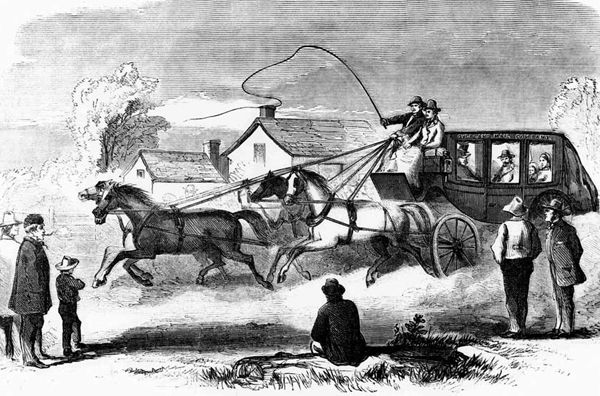

Light stagecoach.

William Buckley of Watertown, New York, headed this party. Bands of mounted Comanche attacked them on the lonely Staked Plains of western Texas, and Apache crept upon them in the mountains of southwestern New Mexico. History contains no record of the battles they fought, but they went on driving the Mexican laborers to their toil under the hot sun, and the chain of low adobe buildings crept slowly westward.

In those days, Mexican outlaws were drifting into Arizona and New Mexico from Chihuahua and Sonora, and these cutthroats, to whom murder was a means of livelihood, were as great a menace as the Indians. Three of them got jobs in the station building gang and awaited an opportunity to make money after their bloody fashion. At Dragoon Springs, Arizona, they found their chance.

Here, where the Dragoon Mountains come out into the plain like a lofty granite promontory that faces the sea, the party had completed the walls of a stone corral, within which a storehouse and stage station were partitioned off. The roofing of these two rooms and some ironwork on the gate remained to be completed. The main portion of the party moved on to the San Pedro River, leaving Silas St. Johns in charge of six men to attend to these details. The three Mexican bandits were members of this little detachment. The other three were Americans.

Dragoon Mountains of Arizona.

The place was right on the road, which Apache war parties took to Sonora. For this reason, a guard was maintained from sunset to sunrise. St. Johns always awoke at midnight to change the sentries. One starlit night, when he had posted the picket, which was to watch until dawn, St. Johns went back to his bed in the un-roofed room that was to serve as a station. He dropped off to sleep for an hour and was roused by a noise among the stock in the corral. The sound of blows and groans followed.

St. Johns leaped from his blankets as the three Mexicans rushed into the room. Two were armed with axes and the third with a sledge. The fight that followed lasted less than a minute.

St. Johns kicked the foremost murderer in the stomach and, as the man fell, sprang for a rifle, which he kept in the room. The other two attacked him with their axes. He dodged one blow aimed at his head, and the blade buried itself in its hip. While the man was tugging to free the weapon, St. Johns felled him with a blow on the jaw. The third Mexican struck downward at almost the same instant, severing St. John’s left arm near the shoulder.

Then, the white man got his right hand on his rifle, and the three murderers fled. They had killed one of the Americans who was sleeping in the enclosure, left another dying near him, and the third gasping his last outside the gate.

St. Johns staunched the blood from his wounds and crawled to the top of a pile of grain sacks where he could see over the un-roofed wall. Here, he stayed for three days and three nights. With every sunrise, the magpies and buzzards came in great flocks to sit upon the wall after they had sated themselves in the corral and watch him. With every nightfall, the wolves slunk down from the mountains and fought over the body outside the gate. Night and day, the thirst-tortured mules kept up a commotion.

A road-grading party finally came along on Sunday morning. They gave St. Johns as first aid as possible and sent a rider to Fort Buchanan for a surgeon. The doctor amputated the arm nine days after the wound had been inflicted. Three weeks later, St. Johns could ride a horse to Tucson.

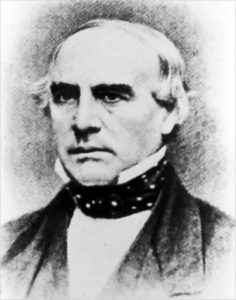

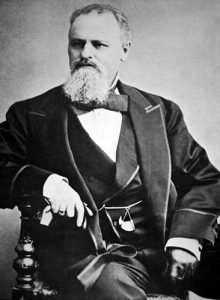

John Butterfield.

Silas St. Johns is offered as a sample of the men who built and operated the overland mail lines. There were many others like him among the drivers, stock-tenders, and messengers. Ironmen were not easy to kill, and so long as there was breath in their bodies, they kept on fighting.

John Butterfield and his associates were made of the same stuff as these employees.

It is not known how many hundred thousand dollars these pioneer investors put into their line before the turning of a single wheel; it must have been somewhere near a cool million, and this was in a day when millions were not as common as they are now—a day, moreover, when nothing in the business was certain, and everything remained to be proved.

They established over 100 stage stations along that semicircle through the savage Southwest. They bought about 1,500 mules and horses and sent them out along the route. Hay and grain were freighted, in some cases, for 200 miles to feed these animals, and the loads arrived at the corrals worth a good fraction of their weight in silver. There was a station in western Texas to which teamsters had to haul water for nine months of the year from 22 away. At every one of these lonely outposts, there was an agent and a stock-tender, and at some, it was necessary to maintain what amounted to a little garrison. Arms and ammunition were provided for defense against the Indians and outlaws; provisions were laid to last for weeks. One hundred Concord coaches were purchased from the Abbot Downing Company, which had been manufacturing these vehicles in New Hampshire since 1813; they were built on the thorough-brace pattern and regarded as the best that money could buy. Seven hundred and fifty men, of whom 150 were drivers, were put on the payroll and transported to their stations.

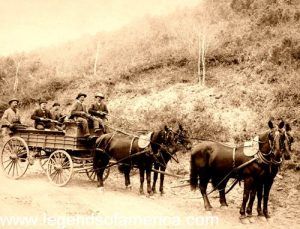

The Butterfield stage starts its journey in Tipton, Missouri.

Nearly all this outlay was made before the beginning of the first trip. It was the most significant expenditure of money on a single transportation project of its kind up to this time in America. And there were a thousand hazards of the wilderness to be incurred, a thousand obstacles of nature to be overcome before the venture could be proved practical.

The men of money had done their part, and the line was ready for the traffic opening. On September 16, 1858, the mail sacks started from St. Louis and San Francisco. It was up to the men of action to get them through within the schedule.

Twenty-five days was the allowance for the 2760 miles. The westbound coach reached San Francisco about 24 hours inside of the limit. On that October evening, crowds packed Montgomery Street; the booming of cannons and the crashing of anvils loaded with black powder, the blaring of brass bands, and the voices of orators all mingled in one glad uproar to tell the world that the people by the Golden Gate appreciated the occasion.

Missouri Pacific Railroad.

In St. Louis, the eastbound mail was an hour earlier. John Butterfield stepped with the sacks from the Missouri Pacific train, and a grand procession was on hand to escort him to the post office. Bands, carriages, and a tremendous red, white, and blue display enlivened the city. President Buchanan sent a telegram of congratulation.

It looked as if the northern route was out for good now, but the men still had to keep the southern line in operation. What had been done was only a beginning; the long grind of real accomplishment still lay ahead.

Storms, floods, Indian massacres, and hold-ups were common, but the line carried on. The stock was, for the most part, unbroken. At nearly every change, the fresh team started on a mad gallop, and if the driver had a vast plain where he could let them go careening through the mesquite or greasewood while the stage followed, sometimes on two wheels, sometimes on one, he counted himself lucky. There was many a station from which the road led over the broken country — along steep sidehills, across high-banked washes, skirting the summits of rocky precipices. On such stretches, it was the rule rather than the exception for the coach to overturn.

The bronco stock was bad enough, but the green mules were the worst. It was often found necessary to lash the stage to a tree — if one could be found near the station, and if not to the corral fence — while the long-eared brutes were being hooked up. When the last trace had been snapped into place, the hostlers would very gingerly free the vehicle from its moorings and, as the ropes came slack, leap for their lives.

They called the route a road. That term was a far-fetched euphemism. In some places, approaches had been dug away to the beds of streams, and the impassable barriers of the living rock had been removed from the mountain passes. But that was all. With the long climbs upgrade and the bad going through loose sand or mud, it was always necessary for the driver to keep his six animals at a swinging trot when they came to a level or a downhill pull. Often, he had to whip them into a dead run for miles, where most men would hesitate to drive a buckboard at a walk.

During the rainy seasons, the rivers of that Southwestern land demonstrated that they had a right to the name — to which they never pretended to live up at other times — by running bank full. Thick strata of quicksands underlay these coffee-colored floods. Occasionally, one of them absorbed a coach, and unless the driver was very swift in cutting the traces, it took unto itself two or three mules for good measure.

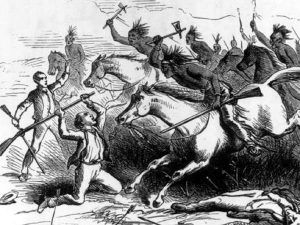

Comanche Attack.

The Comanche Indians were on the warpath during these years in western Texas. On the great Staked Plain, they swooped down on many stages, and the driver and passengers had to make a running fight of it to save their scalps. The Indians attacked the stations, 200-300 of them in a band. The agents and stock tenders, who were always on the lookout, usually saw them in time to retreat inside the thick adobe walls of the building, from which shelter they sometimes could stand them off without suffering any particular damage. But, other times, they were forced to watch the enemy go whooping away with the stampeded stock from the corral. And, now and again, there was a massacre.

Under Mangas Coloradas, whom historians call their greatest war chief, the Apache were busy in New Mexico and Arizona. They worked more carefully than their Texan cousins, and there was a gorge along the line in that section, which got the name of Doubtful Canyon because the only thing a driver could count on there, with any certainty, was a fight before he got through to the other side.

Indians attacking stagecoach.

Nor were the Indians the only savage men in that wilderness. Arizona was becoming a haven for fugitives from California Vigilante Committees and renegade Mexicans from the South. The road agents went to work along the route, and near Tucson, they had a thriving business.

Yet, despite all these enemies and obstacles, the Butterfield Overland Mail was only late three times.

Despite bad roads, floods, sandstorms, battles, and hold-ups, the east and westbound stages usually made the distance in 21 days. And, there was a long period during 1859 when the two mails- which had started on the same day from the east and west terminals met each other precisely at the halfway point. The Wells-Butterfield interests had won the struggle. Service was increased to a daily basis, and the compensation was doubled. The additional load was handled with the same efficiency shown in the beginning.

How did these men accomplish these tasks with horses alone? The quality of the men themselves explains that. One can judge that quality by an affair at Stein’s Pass.

“Steen’s Pass,” as the old-timers spelled it — and as the name is still pronounced — is a gap in the mountains just west of Lordsburg, New Mexico. The Southern Pacific Railroad would later come through the same pass. One afternoon, Apache Chiefs Mangas Coloradas and Cochise were in the neighborhood with 600 warriors when a smoke signal from distant scouts told them that the overland stage was approaching without an armed escort. The two chieftains posted their followers behind the rocks and awaited the arrival of their victims.

When one remembers that such generals as Crook have expressed their admiration for the strategy of Cochise and that Mangas Coloradas was the man who taught him, one will realize that Stein’s Pass, which is admirably suited for all purposes of ambush, must have been an efficient death-trap when the Concord stage came rumbling and rattling westward into it on that blazing afternoon.

There were six passengers in the coach, all of them old-timers in the West. Called the Free Thompson party, from the name of the leader, every one of these men was armed with a late-model rifle and took full advantage of the company’s rule, which allowed the carrying of as much ammunition as one pleased. They had several thousand rounds of cartridges.

Apache at the Ford, Edward S. Curtis, 1903.

Such a seasoned company as this was not likely to go into a place like Stein’s Pass without taking a look or two ahead, and 600 Apache warriors were sure to offer some evidence of their presence to keen eyes. This would probably explain why the horses were not killed at once. The driver got the coach to the summit of a low bare knoll a little way off the road, where the Free Thompson party made their stand on the hilltop.

They were remarkable men, uncursed by the fear of death, the sort who could roll a cigarette or bite a mouthful from a plug of chewing tobacco between shots and enjoy the smoke or the cud, the sort who could look upon the advance of overwhelming odds and coolly estimate the number of yards which lay between.

The place where they made their stand was far from water, on a bare hilltop with few rocks to provide cover. A burning sun was above them, and a ring of yelling Apache warriors surrounded them.

You can picture those seven men with their weather-beaten faces, old-fashioned slouching wide-rimmed hats, and breeches tucked into their boot-tops. You can see them lying behind those boulders with their leathered cheeks pressed close to their rifle stocks, their narrowed eyes peering along the lined sights, and then, as time went on, crouching behind the bodies of their slain horses.

And, you can picture the turbaned Apache with paint-smeared faces creeping on their bellies through the clumps of coarse bear grass, gliding like bronze snakes among the rocks, coming closer every hour.

Night followed day; hot morning grew into scorching noon tide; the full flare of the Arizona afternoon came on, and night again. The rifles cracked in the bear grass. Thin jets of pallid flame spurted from behind the rocks. The bullets kicked up little dust clouds. And, so, it went for three days and three nights, for it took those 600 Apache that length of time to kill the seven white men. But, before the last of them died, the Free Thompson party slew between 135 and 150 Indians.

In later years, Cochise told of the battle. “They were the bravest men I ever saw,” he said. They were the bravest men I ever heard of. Had I 500 warriors such as them, I would own all of Chihuahua, Sonora, New Mexico, and Arizona.”

That was the breed of men who kept the Butterfield Stage line open, and the affair at Stein’s Pass is cited to show something of their character, although it took place after the company began removing its rolling stock. In 1860, Russell, Majors & Waddell accomplished a remarkable coup, bringing the overland mail to the northern route.

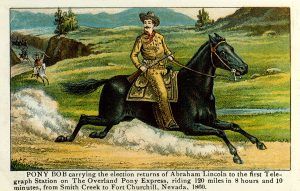

Pony Bob Haslam.

They performed the most daring exploit in the history of transportation. The story of their venture bristles with action; such names as Wild Bill Hickok, Pony Bob Haslam, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Colonel Alexander Majors adorn it.

Colonel Majors held the broad horn record on the old Santa Fe Trail – 92 days on the round trip with oxen. He was the active spirit of the firm of Russell, Majors & Waddell. In 1859, these magnates of the freighting business had more than 6,000 massive wagons and more than 75,000 oxen on the road between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Salt Lake City, Utah, hauling supplies for government posts and mining companies, and operating a stage line to Denver where gold excitements were bringing men in droves.

One day in the winter of 1859-60, Senator W. M. Gwin of California met with Majors’ senior partner, William H. Russell, and several New York capitalists in Washington. Senator Gwin proposed a plan to show the world that the St. Joseph-San Francisco route was practical throughout the year.

That scheme would become the Pony Express – men on horseback with fresh relays every 10-12 miles to carry letters at top speed across the wilderness. Congress had pigeonholed his bill to finance such a venture. He urged now that private capital undertake it and talked so convincingly that Russell committed himself to enlist his partners in the enterprise.

Russell returned to Leavenworth, Kansas, the firm’s headquarters, and brought the matter to Majors and Waddell. They showed him in a few minutes that he had been talked into a sure way of losing several hundred thousand dollars. But he reminded them that he had committed himself to the undertaking. They said that settled it; they would stand by him and make his word good.

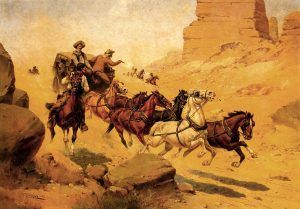

Their stage line had stations every 10-12 miles as far as Salt Lake City; beyond that point, there was not a single building; but, within two months from the day when Russell had that talk with Senator Gwin, the firm had completed the chain of those stations all the way Sacramento, purchased 500 half-breed mustang ponies which they apportioned along the route, hired 80 riders and what stock tenders were necessary, and hauled feed and provisions out across the intermountain deserts and droves of mules beating down trails through the deep drifts of the Sierras and the Rockies.

First Ride of the Pony Express.

On April 3, 1860, Henry Roff swung into the saddle at Sacramento, and Alexander Carlyle leaped on a brown mare in St. Joseph, Missouri. While cannons boomed and crowds cheered in those two remote cities, the ponies approached each other from the ends of that 2,000-mile trail on a dead run.

At the end of ten miles or so, a relay mount was waiting for each rider. As he drew near the station, each man let out a long coyote yell, and the hostlers led his animal into the roadway. The messenger charged down upon them, drew rein, sprang to the earth, and while the agent lifted the pouches from one saddle to the other, he gained the back of his fresh horse and sped on. At the end of his section, which might vary from 75-125 miles, each rider dismounted for the last time and turned the pouches to a successor.

In this manner, the mail traveled across the prairie and sagebrush plain, through mountain passes where the snow lay deep beside the beaten trail, and across the vast, silent reaches of the Great American Desert. The first trip took ten days for both eastbound and westbound pouches.

The riders were light of weight and were allowed to carry no weapons save a bowie knife and revolver. The letters were written on tissue paper. The two pouches were fastened to a leather covering that fitted over the saddle, and the thing was lifted with one movement from the last horse to the relay animal.

Many of these half-breed mustangs were unbroken; some were famous for their ability to buck. But, bad horses were a part of the game; like evil men, everyone in the business expected them and took them as a matter of course. The riders of the Pony Express hardly recall such incidents because of the more extensive adventures with which their lives were filled.

Jim Moore’s ride was long famous among the frontier exploits. His route went from Midway station to old Julesburg, Colorado, 140 miles across the Great Plains of western Nebraska. The stations were 10-14 miles apart. Arriving at the end of that grueling journey, he rested for two days before returning.

One day, Moore started westward from Midway station, knowing that his partner, who carried the mail one way while he was taking it the other, was sick in Julesburg. It was a question of whether the man could take the eastbound pouches; if he should not, there was no substitute.

Realizing what might lie ahead, Moore pressed each fresh horse to its utmost speed during that westward ride. A man can endure only so long a term of punishment, and he resolved to save himself what minutes he could initially. He made that 140 miles in eleven hours.

The partner was in bed, and there was no hope of his rising for a day or two. The weary messenger started toward one of the bunks to get some rest, but before he had thrown himself on the blankets, the coyote yell of the eastbound rider sounded up the road.

It was up to Moore to take the sick man’s place now. While the hostlers were saddling a pony and leading it out in front of the station, he snatched some cold meat from the table, gulped down a cup of lukewarm coffee, and hurried outside. He was just in time to swing into the saddle. He clapped spurs to the pony and kept him on a run. So, with each succeeding mount, and when he arrived at Midway, he had put the 280 miles of the round trip behind him in 22 hours.

Paiute Indians.

In western Nevada, where the Paiute Indians were on the warpath, several stations were little forts, and riders frequently raced for their lives to these adobe sanctuaries. Pony Bob Haslam made his great 380-mile ride across this section of scorching desert.

He rode out of Virginia City one day while the inhabitants were frantically working to fortify the town against war parties whose signal fires were blazing on every peak for 100 miles.

When he arrived at the Carson River, 60 miles away, he found that the settlers had seized all the horses at the station for use in the campaign against the Indians. He went on without a relay down the Carson River to Fort Churchill, 15 miles farther. Here, the man to relieve him refused to take the pouches.

Within ten minutes, Haslam was in the saddle again. He rode 35 miles to the Carson Sink, got a fresh horse, and made the next 30 miles without a drop of water; changed at Sand Springs and again at Cold Springs, and after 190 miles in the saddle, turned the pouches over to J.G. Kelley.

Here, at Smith’s Creek, Pony Bob got nine hours’ rest. Then, he began the return trip. At Cold Springs, he found the station a smoking shambles; the keeper and the stock-tender had been killed, and Indians drove off the horses.

Virginia City, Nevada, 1866.

It was growing dark. He rode his jaded animal across the 37-mile interval to Sand Springs, got a remount, and pressed on to the sink of the Carson River. Afterward, it was found that during the night, he had ridden straight through a ring of Indians who were headed in the same direction as he was going. From the sink, he completed his round trip of 380 miles without a mishap, arriving within four hours of the scheduled time.

Nine months after the line’s opening, the Civil War began, and the Pony Express carried the news of the attack on Fort Sumter from St. Joseph to San Francisco in eight days and 14 hours.

Newspapers and businessmen had awakened to the importance of this quick communication, and bonuses were offered for delivering important news ahead of schedule. President Buchanan’s last message had held the record for speedy passage, going over the route in seven days and 19 hours. But, that time was beaten by two hours in the carrying of President Lincoln’s inaugural address. Seven days and 17 hours — the world’s record for transmitting messages by men and horses!

The Russell, Majors & Waddell firm spent 700,000onthePonyExpressduringits18monthsofexistenceandtookinlessthan700,000 on the Pony Express during its 18 months of existence and took in less than 700,000onthePonyExpressduringits18monthsofexistenceandtookinlessthan500,000. But they accomplished what they had set out to do. In 1860, the Butterfield line was notified to transfer its rolling stock to the west end of the northern route; their rivals got the mail contract for the eastern portion.

The Wells-Butterfield interests were on the underside now. The change to the new route involved enormous expense, and with the withdrawal of troops at the beginning of the Civil War, Apache and Comanche Indians plundered the disintegrating line of stations. The company lasted briefly on the west end of the overland mail and retired. Its leaders then devoted their energies to the express business.

Ben Holladay.

At this juncture, a new man got the mail contract – Ben Holladay. He had begun as a small storekeeper in Weston, Missouri, and made one canny turn after another until, at the time when the mail came to the northern route, he owned several steamship lines and had significant freighting interests. He was beginning to embark on the stage business. The firm of Russell, Majors & Waddell was losing money, partly due to inadequate financial management and partly to the courageous venture of the Pony Express. Holladay absorbed their property early in the sixties. He was the transportation magnate of his time, the first American to force a merger in that industry.

One of his initial steps was to improve the operation of the stage line. Some of his subordinates’ efficient methods were picturesque. In Julesburg, near the mouth of Lodge Pole Creek in northeastern Colorado, the agent was an old Frenchman, after whom the place had been named. This Jules had been feathering his own nest at the expense of the company, and the new management supplanted him with one Jack Slade, whose record up to that time was an estimated 19-20 killings. Slade was put in charge of Julesburg with instructions to clean up his division.

While the new superintendent was exterminating such highway robbers and horse thieves as Jules had gathered about him in this section, his predecessor was biding in the little settlement, watching for a chance to play even. One day, Slade came into the general store near the station, and the Frenchman, who had seen a good opportunity for an ambush, fired both barrels of a double-barreled shotgun into his body at a range of about 50 feet.

Slade took to his bed. But, he was made of the stuff that absorbs much lead without any permanent harm. He was up again in a few weeks. He hunted down Jules, who had taken refuge in the Indian country to the north on hearing of his recovery. He brought the prisoner back to Julesburg and bound him to the snubbing post in the middle of the stage company’s corral.

Accounts of what followed differ. Some authorities maintained that Slade killed Jules. Others, who based their assertions on the statements of men who said they were eyewitnesses, told how Slade enjoyed himself for some time filling the prisoner’s clothing with bullet holes and then exclaimed, ”Hell! You ain’t worth the lead to kill you.” And turned the victim loose. But, all narrators agree on this: before Slade unbound the living Jules — or the dead one, whichever it may have been — he cut off the prisoner’s ears and put them in his pocket.

It may be noted in passing that this truculent efficiency expert went wrong years after and wound up his days at the end of a rope in Virginia City, Montana.

Ben Holladay carried the mail overland throughout the early sixties. But, during the summer of 1864, the Indians of the plains, for the first time in their history, made a coalition. They united in one grand war party against the outposts along the line, and for a distance of 400 miles, they destroyed stations, murdered employees, and made off with livestock. The loss to the company was half a million dollars.

It crippled Holladay, and the government so delayed consideration of his claims for reimbursement that he was glad to sell the property. The firm of Wells Fargo, which had been increasing its express business until it virtually monopolized that feature of common carrying throughout the West at the close of the Civil War, took the line over. It was the old Wells Butterfield Co. again. The first winners in the struggle were the last.

Wells Fargo Express.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

About This Article: Much of this article was excerpted from the book When the West Was Young by Frederick Ritchie Bechdolt; The Century Co., New York, 1922. However, the text as it appears here is far from verbatim, as it has been heavily edited for clarification, truncated, and updated for the modern reader.

Also See:

Adventures & Tragedies on the Overland Trail