The Santa Fe Trade – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By Helen Haines, 1891

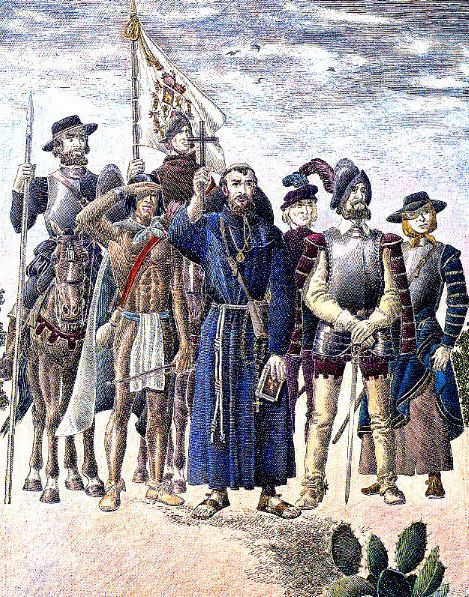

The Spanish in present-day New Mexico.

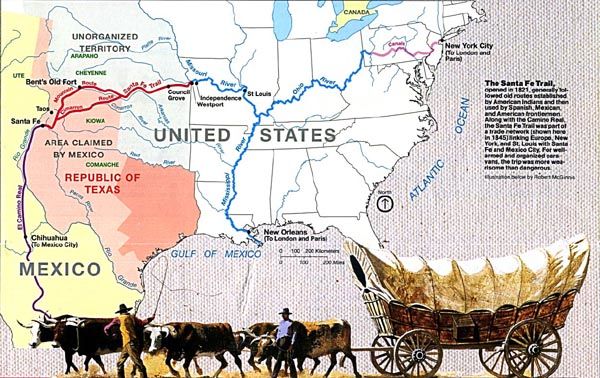

The acquisition of Louisiana by the United States marked a distinct era in the history of New Mexico. Before this period, the Spanish provinces had been isolated, as it were, from the rest of the world. Now that this enormous tract had become American territory, the ancient barriers couldn’t remain. Within ten years from the date of the purchase, a fluctuating but steadily increasing intercourse had sprung up between the Western cities of the United States and the northern provinces of Mexico. As this overland commerce was called, the Santa Fe trade had no definite origin but was instead the result of an accident than any organized plan. Beginning with the desultory traffic carried on with the Indians by Spanish and American trappers, its scope gradually extended until the distant cities of Santa Fe and Chihuahua had become markets for the commodities of the eastern coast, and the Santa Fe trade was a recognized feature of American commerce.

James Pursley, a Kentuckian, was the first American to penetrate the wilds of Louisiana and enter New Mexican territory. However, Baptiste Lalande, a French Creole who reached the province in 1804, celebrated his arrival at Santa Fe. Early this year, Lalande was dispatched on a trading expedition by William Morrison, a merchant of Kaskaskia, Illinois — then one of the extreme frontier settlements, a few miles above St. Louis, Missouri, on the eastern side of the Mississippi River. He was furnished with the necessary articles for barter with the Indians. His orders were to push up the Platte River, make his way, if possible, to Santa Fe, and report on the prospects of commercial intercourse between that city and the United States. After an arduous journey, Lalande reached the Rocky Mountains; then, he dispatched a party of Indians into Mexico to inform the authorities of the arrival of this stranger from the distant East. A mounted troop of Spaniards set out at once and brought the trader and his goods to a small settlement some miles north of Taos, New Mexico. From Taos, Lalande proceeded southward to Santa Fe, disposing of his merchandise as he journeyed on and making profits that exceeded his utmost expectations.

So well was the enterprising Baptiste pleased with the country, its inhabitants, and its possibilities in the line of trade that he gave up all thoughts of returninEastst and settled himself in business at the capital upon the funds supplied by Morrison, to whom he neither forwarded remittances or accounted for the proceeds of the adventure. It was to collect the amount due the merchant of Kaskaskia that Dr. John Robinson, of Zebulon Pike’s party, proceeded to Santa Fe.

It was in 1805 that James Pursley, famous as the first to discover gold in what is now Colorado, entered New Mexico. A native of Baird’s Town, Kentucky, he left St. Louis, Missouri, in 1803 with three companions. He traveled to the Osage River’s headwaters and trapped and traded with the Indians. After many exciting adventures, in which his daring won Pursley the title of “The Mad American,” the four hunters were capsized in a rough canoe of their construction at the junction of the Osage and Missouri Rivers, losing their entire stock of peltries — the fruit of a whole year’s hunt. They managed to save arms and ammunition and were hailed by a Frenchman descending the Missouri River to trade with the Mandan Indians. Pursley embarked with him for the voyage and was sent out on a hunting and trading expedition early in the following spring with a large band of Paducah and Kiowa Indians and a small quantity of merchandise. They were attacked by Sioux and driven from the plains into the mountains of Colorado, where the unwieldy party — which numbered nearly 2,000 men and 10,000 animals — wandered along the headwaters of the Platte River.

South Platte River, Colorado.

Here, Pursley observed strong indications of gold-bearing deposits and obtained some of the virgin mineral, which he carried in his shot pouch for several months. Believing he would never succeed in reaching a civilized region and feeling that the precious metal was worthless in the wilderness, he threw his samples away from sheer weariness and disgust. After journeying some distance along the Platte River, the Indians, knowing they must be close to New Mexico, sent Pursley and several of their number to Santa Fe to see if the Spanish authorities would allow them to enter the province and trade with the people. Governor Alencaster granted this request, and the Indians returned for the remainder of the company, who departed for the East after disposing of their merchandise at profitable prices. But Pursley, now that he had finally reached a civilized community, did not choose to trust himself to the perilous journey across the plains. He reached Santa Fe in June 1805 and established himself as a carpenter in that city. In 1807, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike saw him as having made much money and a man of strong natural sense and undoubted courage. Although well treated by the authorities, Pursley was placed under continual surveillance; he was forbidden to write or send any communication to the East and was obliged to give bonds that he would not leave the country without permission from the government. This was probably due to his having imprudently mentioned his discovery to the Spaniards, who were very anxious that he should conduct a cavalry detachment to the spot where the gold had been found. But, the sturdy pioneer, believing the locality to be within the territory of the United States, steadfastly refused to divulge the secret, — for which firmness the citizens of the Centennial State certainly owe him their deepest gratitude.

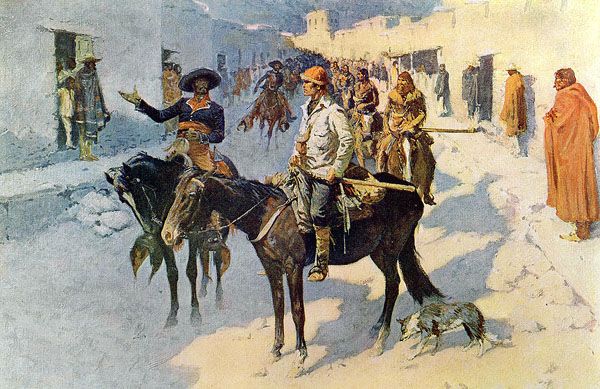

Zebulon Pike entering Santa Fe, New Mexico by Frederic Remington.

For the next five years, nothing is known of any Spanish-American intercourse, though it is probable that fragmentary traffic was kept up. Still, the return of Lieutenant Zebulon Pike and the relation of his travels, published in 1810, stimulated general interest in the subject. The lieutenant’s account of the high prices prevailing throughout the North Mexican provinces and the immense profits to be reaped by enterprising traders spread like wildfire through the eastern settlements. Many of the adventurous frontiersmen — hunters, traders, and trappers, the typical pioneers of those days — determined to make their way across the unknown region of Louisiana to this new land of promise. In 1812, an expedition was organized under the direction of Robert McKnight, James Beard, Peter Chambers, and several others, all of whom were part of a party of nine or ten. Believing that the revolutionary movement under Hidalgo, in 1810, had completely removed the old restrictions on trade, which rendered all foreign intercourse, except by special permission of the Spanish government, illegal, they crossed the prairies to New Mexico, following the directions of Lieutenant Pike.

Their route, the only one then known, was westward to the Colorado mountains and down the Rio Grande to Taos, New Mexico, and after a long but uneventful journey, they reached Santa Fe. Their arrival at the capital could not have been more inopportune. The liberal principles fostered by Hidalgo had just been vigorously quenched, the revolutionary leader had been arrested and shot, the royalists were once more supreme, and all foreigners, but especially Americans, were believed to be the agents of a new revolution and were objects of the most intense suspicion. The unfortunate traders, who were as yet hardly aware of their dangerous situation, were instantly arrested as spies, their entire stock of merchandise confiscated, and themselves taken to the jails of Chihuahua and Durango, where they were rigorously confined for nine years. During this period, Congressman Scott of Missouri made several efforts to release them. Secretary Adams sent letters to the king of Spain and the ruler of Mexico, but nothing was affected. It was not until 1822, when the revolutionary party under Augustine de Iturbide became once more predominant, that the unfortunate Americans were set at liberty by order of the new emperor of Mexico.

Auguste Chouteau.

Before McKnight and his unlucky companions returned in 1815, Julius de Mun and Auguste P. Choteau proceeded with a large party to the waters of the Upper Arkansas River, where they hunted and traded with the Indians. A year later, they entered New Mexico and visited Taos and Santa Fe; at the latter place, they were hospitably received by Governor Mainez, who gave them full liberty to hunt and trade north of the Red River and East of the mountains. Notwithstanding this permission, in June 1817, during the governorship of Don Pedro Allende, a force of Spanish dragoons arrested Choteau, De Mun, and 24 others and brought them to Santa Fe, also opening the caches made by the trappers and taking articles to the value of over $30,000. At the capitol, the Americans were court-martialed, imprisoned for two days, and dismissed without recovering their property. They immediately returned to St. Louis and entered a suit for damages against the New Mexican authorities; the action dragged on until 1836, and it is unknown if it was ever definitely settled.

William Becknell blazes the Santa Fe Trail.

Notwithstanding the personal misfortunes of these early adventurers, their narratives only induced others to fit out expeditions. In 1822, an Ohio merchant named Hugh Glenn, who kept a small trading station at the mouth of the Verdigris River, fitted out a party and proceeded by a circuitous route up the Arkansas River toward the mountains, encountering many dangers and privations but finally reaching Santa Fe in safety. In this same year, Captain William Becknell of Missouri, with four friends, started from the vicinity of Franklin, in his native State, with the intention of trading with the Comanche. Near the mountains, he met a party of Mexican rangers who induced the Americans to accompany them to New Mexico, where, though their stock of merchandise was small and of little value, the expedition members cleared a handsome profit. The captain returned to Missouri alone the following winter, leaving his company at Santa Fe. His favorable reports stimulated others to embark on the trade. In May 1823, Colonel Cooper, with his sons and ten others, left Franklin with $5,000 worth of goods, transported by pack-horses, and safely arrived at Taos.

Captain Becknell’s second expedition met with a very different fortune; pleased with his former success and confident of still richer profits, he set out with a company of 30 men carrying $5,000 in merchandise. In his eagerness to reach his destination, the captain resolved to abandon the circuitous route heretofore followed and, having reached the caches on the Arkansas River, directed his course straight toward Santa Fe. “With no other guide than the starry heavens, or, it may be, a pocket compass,” said Dr. Josiah Gregg, “the party embarked upon the arid plains which extended far and wide before them to the Cimarron River. The adventurous band pursued their forward course without being able to procure any water except the scanty supply they carried in their canteens; this was utterly exhausted after two days’ march, and the sufferings of the men and beasts drove them almost to distraction. They were reduced to the cruel necessity of killing their dogs and cutting off the ears of their mules in the vain hope of assuaging their burning thirst with the hot blood; this only served to irritate the parched palate and madden the senses of the sufferers. Frantic with despair at the prospect of the horrible death that stared them in the face, they scattered in every direction in search of water. Frequently led astray by the deceptive glimmer of the mirage, or false ponds, as these treacherous oases of the desert are called, they resolved to retrace their steps to the Arkansas River but were unequal to the task and would undoubtedly have perished had not a buffalo, fresh from the riverside, with a stomach distended with water, been discovered just as the last rays of hope were receding. The hapless intruder was dispatched, and a draught procured from its stomach. I have since heard one of the party declare that nothing ever passed his lips that gave him such exquisite delight as his first draught of that filthy beverage. This relief enabled some of the strongest men of the party to reach the river, where they filled their canteens and hurried back to the assistance of their comrades. By degrees, they were all enabled to renew their journey and, following the course of the Arkansas River for several days, reached Taos, 60-70 miles north of Santa Fe.

Santa Fe Trail Trader.

From 1821 to 1822, the real commencement of the Santa Fe trade occurred. The caravans increased in size and value from this period, and the worth of the merchandise transported rose gradually from 5,000to5,000 to 5,000to80,000. The fall of Spanish authority and the establishment of the Mexican government removed many restrictions on the progress of the intercourse. They swelled the ranks of the traders, who found the profits of their enterprises enormous, even considering the cost and difficulty of transportation. Before establishing trade with the United States, New Mexico had depended entirely upon the Spanish market or the fluctuating products of Mexico for her supplies. Following the usual selfish policy of Spain, all manufactured articles were imported to the colonies from Spanish ports in return for exports of raw materials. Although profitable for the mother country, this was hard on the colonists, who were forced to pay exorbitant prices for even the cheapest manufactured goods. Indeed, so odious were these restrictions on commerce considered that in 1771, Viceroy Bucareli informed the king that trade could never prosper in Mexico until the monopoly enjoyed by the merchants of Cadiz should be removed, and begged that the colonists be allowed, at least, to remit their funds to Spain and bring back the return freights in vessels of their own.

For this reason also, the war between Spain and England, in the last years of the 18th century, was of great advantage to Mexico, for, as the seas were filled with the enemy’s cruisers, the Spaniards dared not send out large amounts of coins and their trade was confined chiefly to exports from the mother country. Thus, the immense product of the Mexican mines was retained in the country, and home industries flourished. Many of the internal provinces and the cities of Oaxaca, Guadalajara, and Ixtlahuaca, manufacturing large quantities of silk, cotton, and wool. Notwithstanding this growing activity in Mexican commerce, these infant industries were inadequate to supply the demand. All manufactured articles commanded extravagant prices, especially in the northern provinces, where transportation expense was added to the original cost — the citizens of Santa Fe paying two and three dollars per yard for the coarsest calicoes and cheapest domestic cloths. It can be imagined that the reports of these prices and the profits attendant upon them should have impelled American merchants to send their goods to these remunerative markets, where the gains of one expedition doubled the cost of outfit and transportation.

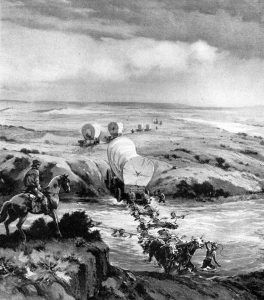

Santa Fe Trail Caravan.

The next event of importance in the annals of the Santa Fe trade was the introduction of wagons; up to 1824, all goods were transported by pack mules, which necessarily limited the amount and value of the freight, but in that year, the caravans, which departed from Missouri employed not only the usual quota of mules but 25 wheeled vehicles, principally what were then called “Dearborn carriages.” The experiment proved entirely successful, and from this period, wagons were exclusively used, some of them being of great size and drawn by 10 or 12 mules. In the first years of the trade, horses were used to draw the vehicles as mules were scarce and expensive, but as soon as the latter could be procured in abundance, horses were discarded except for riding purposes. In 1829, oxen were tried and found, much to the surprise of the traders, to be perfectly capable of performing the duties of the trip. From this time onward, the number of oxen and mules employed in the business was about equal; the greater endurance and speed of the latter balanced the former’s superiority in cheapness and strength.

The caravans started at Franklin on the Missouri River, 150 miles west of St. Louis. Still, in 1831, the proportions of the trade had so increased that some spot nearer the western frontier was considered necessary. The choice fell upon Independence, Missouri, situated about twelve miles from what is now Kansas, then known as “the Indian border,” and three miles south of the Missouri River. This place gradually became the point of outfit, departure, and debarkation; here repaired the adventurer about to embark on his trading enterprise; here were procured provisions, mules, oxen, and sometimes wagons; and here the final preparations for the long journey across the plains were made. Not only was Independence the starting point of the Santa Fe caravans, but the Rocky Mountain traders, trappers, and emigrants to Oregon took this town on their route. During the season of departure- usually in May- it was a place of much bustle and activity; “here,” said Josiah Gregg, “were seen men of every class, with a little sprinkling of the softer sex. The fustian frock of the city-bred merchant, furnished with a multitude of pockets, could contain a variety of extra tackling; the backwoodsman in linsey or leather hunting shirt; the farmer, with his blue jean coat, and the wagoner, with a flannel-sleeved vest.”

Among the weapons noted were “the rifle for the frontiersman, the double-barreled fowling-piece for the sportsman, scatterguns, repeating arms, pistols, and knives.” Organizing a caravan was no light; the first step was the election of an officer entitled “Captain of the Caravan,” the expedition commander whose authority was never questioned. By him, each proprietor was notified to furnish a list of his men and wagons; if the company was a large one, all the vehicles were divided into four divisions, and a lieutenant was appointed whose duty it was to inspect every ravine and creek along the route, select the crossings, superintend the encampment, and generally look after the arrangement of the wagons; watches were also appointed, usually eight in number, to stand guard a quarter of each alternate night. Besides personal arms, the caravan often carried one or two small cannons mounted on carriages. The merchandise was packed with the utmost care, a task requiring no little skill but in which many became adept, filling the wagons with such evenness that on their arrival at Santa Fe, not one article would be disturbed or injured. A ” Santa Fe assortment,” as it was called, consisted generally of merchandise usually seen in the smaller retail stores of the East, viz: woolen and cotton goods, silks, hardware, notions, etc. The principal articles in demand were cotton velvets and domestic cotton; the latter, which were by far the most called for, were brown, unbleached, and blue and formed almost half of every assortment; despite their ready sale, however, they were the most unprofitable articles taken, on account of their weight and the heavy-duty imposed upon them by the Mexican authorities who, in 1837, issued a decree prohibiting the entrance of all shirtings, calicoes, and drillings. American manufacturers alone were in demand, with British cotton being much less durable and having a lighter texture. Besides the merchandise, provisions for the men were carried, consisting chiefly of bacon, flour, coffee, sugar, and salt — buffaloes furnishing all the fresh meat used on the journey.

Santa Fe Trail Map.

The train left Independence in detached parties and rendezvoused at Council Grove, Kansas, about 150 miles distant on a branch of the Neosho River; here, all arrangements were completed for the journey, and the “Catch up! catch up!” of the captain rang out from his station in the foremost wagon, the answering shouts of “All’s set!” from the drivers proclaimed that everything was in readiness. In a few moments, the caravan was on its way to Santa Fe. The appearance of these long lines of white-topped vehicles was singularly impressive; the wagons advanced slowly in four parallel columns but in broken lines, often with considerable intervals between; the unceasing “Crack! crack!” of the wagoners’ whips, resembling the distant report of musketry, sounded almost as if two hostile parties were engaged in a skirmish. The rear wagons were usually left without a guard, as the horsemen all preferred to be in front, where they could be seen moving in scattered groups, sometimes over a mile in advance. The evolutions of the wagons were intricate and required much skill on the part of the drivers; when marching four abreast, the two exterior lines spread out and then met at the front angle, while the two near lines kept close together until they reached the point of the rear angle when they wheeled suddenly out and closed with the hinder ends of the other two, thus systematically concluding a right-lined quadrangle with a gap left at the rear corner for the introduction of the animals. Every night, the wagons were formed into a hollow square, acting as a defense against Indians and a temporary corral for the cattle; outside of this square, the campfires burned, and the traders slept while those whose turn it was to watch kept guard. The difficulties of the route were all surmounted by the energy of the travelers; in many places, temporary bridges of long grass or brush covered with earth were made, and sometimes “buffalo boats” were constructed by stretching hides over empty wagon bodies or frames of poles.

The End of the Santa Fe Trail by Gerald Cassidy, about 1910.

As the wagons approached within 200 miles of Santa Fe, a party of new couriers, known as “runners,” pushed on in advance to the capital; they were generally proprietors or agents, and their purpose was to procure and send back a supply of provisions, to secure good accommodations for the merchandise, and, what was no less important, come to an “agreeable understanding” with the custom-house officials. When the crossing of the Red River was reached, the caravan was met and accompanied for the remainder of the journey by a Spanish escort provided to prevent smuggling; here, a branch of the expedition usually proceeded westward to Taos. Five or six days later, the long-expected goal appeared in sight; great was the rejoicing as wagon after wagon descended the steep declivities to Santa Fe; the little cannons fired enthusiastic salutes, the muleteers cheered vociferously, and all were rejoicing and confusion. “I doubt, in short,” said Gregg, “whether the first sight of the walls of Jerusalem was beheld by the crusaders with more tumultuous and soul-enrapturing joy.” “The arrival,” continues the same writer, “produced much bustle and excitement among the natives. ‘Los Americanos!’ ‘Los Carros!’ ‘La entrada d,e la Caravana!’ were to be heard in every direction, and crowds of women and boys flocked around to see the newcomers. The wagoners were by no means free from the excitement on this occasion. They had spent the previous morning rubbing’ up, and now they were prepared, with clean faces, sleek-combed hair, and their choicest Sunday suit, to meet the fair eyes of glistening black that were sure to stare at them as they passed. There was yet another preparation to be made to show off to advantage; each one must tie a brand-new cracker to the lash of his whip, for on driving through the streets and the plaza, everyone strived to outvie his comrades in the skill with which he flourished this favorite badge of his authority.”

The contents of the wagons were soon transferred to the warerooms of the custom house, and the members of the expedition spent a few days recovering from the fatigue of their tedious journey; the wagoners and traders repaired in crowds to the numerous fandangoes which were kept up for some time after the arrival of a caravan, while the merchants were actively employed in more important labors, each endeavoring to get his goods through the custom-house before his neighbor and to supply the country dealers on their annual visit to the capital.

“The derechos de arancel (tariff imposts) of Mexico,” to quote again from Gregg, “are extremely oppressive, averaging about 100%, upon the United States’ cost of an ordinary Santa Fe assortment. Those on cotton textures are particularly so. According to the tariff of 1837 — and it was still heavier before — all plain-wove cotton, whether white or printed, paid twelve and a half cents duty yards, besides the derecho de consumo (consumption duty), which brings it up to at least 15. For a few years, Governor Armijo of Santa Fe established an entirely arbitrary tariff of $500 for each wagon load, whether large or small, of fine or coarse goods! Of course, this was advantageous to traders with large wagons and costly assortments, while it was no less demanding to those with smaller vehicles or coarse, heavy goods. As might have been anticipated, the traders soon took to conveying their merchandise only in the largest wagons, drawn by ten or twelve mules, and omitting the coarser and more weighty articles of trade. This caused the governor to return to the ad valorem system, though still without regard to the tariff general of the nation.”

On about the first of September, four or five weeks after the arrival of the caravan, the return trip was commenced; the number of wagons was significantly reduced, many of those taken being sold in the province, and the return cargo — the profits of the expedition — was of gold-dust or silver bullion, furs, buffalo rugs, wool, and Mexican blankets. The loads generally weighed about 1,200 pounds, and while the outward journey occupied at least 70 days, the homeward trip seldom exceeded 40; indeed, in 1851, Frank X. Aubrey, a young Canadian and well-known scout, made the distance from Santa Fe to Independence in five days and ten hours.

George Sibley

When the trade was well established, several petitions were sent to Congress by the people of Missouri, requesting that a road be marked out and treaties made with the Indian tribes; in January 1825, a bill was passed granting both these requests and appropriating $30,000 for their execution. However, the work was never completed, although energetically begun by the commissioners, Messrs. Reeves, Mathews, and Sibley, and the surveyor, J. C. Brown, who made a treaty with the Osage and commenced the survey. The line of the proposed road was determined as far as the Arkansas River and designated by mounds of earth. Still, it never seemed to have been used by the travelers, who persistently refused to be carried off from the old trail, which had been the route of their predecessors and had the sanction of experience, if not of scientific engineering.

As we can see, the first route followed was by a line almost directly westward to the mountains of Colorado and then south to Taos. Afterward, when the trade assumed importance, a road along the Arkansas River, and then southwest to the Raton Pass was sometimes used, but the route which was the ordinary and favorite one for a long series of years was that along the Arkansas River, then across to the Cimarron River, and so entering New Mexico, proceeding in an almost direct line to the Wagon Mound — which made a conspicuous landmark — and then to Las Vegas, San Miguel, and Santa Fe. In the spring of 1837, an attempt was made, principally by Mexican merchants, to establish an independent trade with Chihuahua, leaving Santa Fe entirely out of the intercourse; but, though begun with much enthusiasm, it was found a losing enterprise and speedily abandoned.

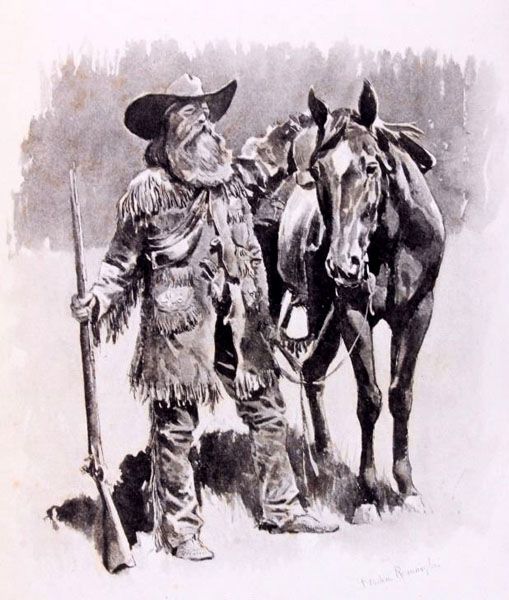

Kit Carson.

The famous scout and Indian fighter Kit Carson first gained his renown by his skill and daring in guiding parties over the Santa Fe Trail, his first trip having been made as far back as 1826; another well-known scout was Colonel Albert G. Boone, grandson of the famous Daniel, who is said to have been able to speak all the Indian languages. Among the early traders and pioneers was James L. Collins, afterward superintendent of Indian affairs in the Territory, who arrived at Santa Fe in 1827 with a caravan of 53 wagons, the largest up to that period. In 1831, Josiah Gregg, whose book, The Commerce of the Prairies, is the authority on all matters about the trade, made his first trip, and in this same year, Captain Jedediah Smith, the well-known Rocky Mountain pioneer, met his death. He had been separated from his party and wandered across the plains in search of water; at last, a small stream was found, but as the captain stooped to drink, he was pierced by a Comanche arrow and died instantly. In 1833, Charles Bent was captain of the annual caravan, which numbered 93 wagons, and the following year, Thomas Kerr commanded an expedition, the profits of which amounted to nearly $200,000. Among the traders of 1835 was the celebrated Captain John Sutter, who established himself in business in Santa Fe, leaving that city for California in 1838.

In the early years of the trade, there was little trouble from the Indians, but as the proportion of the traffic increased. The annual caravans, the period of their passage, and their value became known to the natives, many cruel attacks were made, and the Indians were ever prepared to swoop down upon any straggling bands of traders on their homeward journey or small parties insufficiently supplied with arms, who considered themselves fortunate to escape with only the loss of their animals or goods. The first encounter of this kind recorded took place in 1826 when a party of 12 returning traders encamped upon the banks of the Cimarron River with only four guns between them; here, they were visited by a band of Indians, who noticed their defenseless condition, and after making friendly demonstrations withdrew, only to return with about 30 warriors, each carrying a lasso. They informed the Americans that they wanted some horses, and the traders, unable to resist so large a force, gave them one apiece. But the Indians were not yet contented; each brave must now have two horses. “Well, catch them!” was the acquiescent reply of the unlucky band, upon which the Indians mounted the animals they had just obtained and, swinging their lassoes over their heads, plunged among the stock with furious yells and drove off the entire herd of 500 head of horses, mules, and asses. The first murder committed by Indians took place in 1826. Two young men, members of a returning party named McNees and Monroe, having fallen asleep by a stream known as McNee’s Crossing, were barbarously shot with their guns in full sight of their caravan. The bodies were buried on the banks of the Cimarron River. As the companions of the murdered men were engaged in performing these last services, a small party of Indians, who probably did not know the recent outrage, were seen to advance on the opposite side of the stream. The traders, burning with fury and a desire for vengeance, opened fire upon the Indians, all but one of whom were killed. The survivor bore the tidings to his tribe, who, in their turn, pursued the caravan for days and finally succeeded in carrying off 1,000 heads of stock, although the traders managed to escape. Not satisfied with this bloodless revenge, the Indians a little later attacked a company of 20 men on their homeward trip, killing one and taking all the animals, thus compelling each of the traders to carry his share of the proceeds on his back to the banks of the Arkansas River, where it was cached until a conveyance to the United States could be procured; these shares amounted to $1,000 each, or a load of 80 pounds in silver bullion to each man.

Indian Attack by Frederic Remington, 1907.

These repeated outrages induced the traders to apply for government protection, and in 1829, a United States escort of three infantry companies and one of the dragoons under Major Bennet Riley was detailed to accompany the caravan of that year past the most dangerous portions of the route. The escort stopped at Chouteau’s Island in the Arkansas River. As soon as the traders advanced without its protection, they were attacked by Kiowa warriors. One man was killed, and the assailants disappeared in safety before the arrival of the troops, who were at once summoned. Major Riley and his men remained on the Arkansas River until the autumn when they accompanied the returning caravans to Independence. This was the only protection afforded by the United States until 1834. That year, 60 dragoons under Captain Clifton Wharton acted as special escorts, and again, in 1843, large detachments under Captain Cooke escorted two different caravans as far as the Arkansas River.

From its re-establishment in 1844, the Santa Fe trade continued without interruption, with many wealthy New Mexican merchants participating. It was not seriously affected by the war with Mexico, for the caravan of 1846, in which the United States troops took Santa Fe, contained 414 wagons and merchandise to the value of $1,752,250. Under the American government, the intercourse flourished; not only were the Territories of New Mexico and Arizona supplied, but the northern parts of Mexico also became a market for American goods. With the gradual extension of the railroads, however, the starting place moved further and further westward, the forwarding establishment being transferred from Hays, Kansas, to Sheridan, Kit Carson, Granada, La Junta, El Moro, Las Vegas, and so onward until the railroads were in operation throughout the Territory. No other mode of transportation was necessary.

By Helen Haines, excerpted from History of New Mexico: From the Spanish Conquest to the Present Time, 1530-1890, New Mexico Historical Publishing Company, 1891. The text as it appears here is to verbatim as it has been edited for the modern reader.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2024.

Also See:

Early Traders on the Santa Fe Trail

Santa Fe Trail (Main page)