Fighting the Comanche on the Santa Fe Trail – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By Colonel Henry Inman, 1897

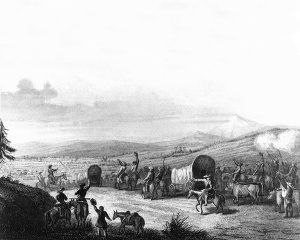

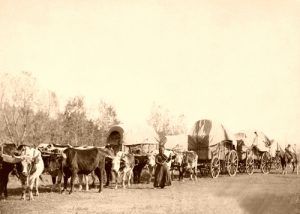

Wagon Train.

Early in the spring of 1828, a company of young men residing in the vicinity of Franklin, Missouri, having heard related by a neighbor who had recently returned the remarkable story of a passage across the great plains and the strange things to be seen in the land of the Mexicans, determined to explore the region for themselves; making the trip in wagons, an innovation of a startling character, as previously only pack-animals had been employed in the limited trade with far-off Santa Fe. The story of their journey can best be told in the words of one of the party:

We had about 1,000 miles to travel, and as there was no wagon road in those early days across the plains to the mountains, we were compelled to take our chances through the vast wilderness, seeking the best route we could. No signs of life were visible except the innumerable buffalo and antelope that were constantly crossing our trail. We moved on slowly from day to day without any incident worth recording. We arrived at the Arkansas River, made the passage, and entered the Great American Desert lying beyond, as listless, lonesome, and noiseless as a sleeping sea. Having neglected to carry any water with us, we were obliged to go without a drop for two days and nights after leaving the river.

Cimarron River.

At last, we reached the Cimarron River, a cool, sparkling stream, and our animals were on the point of perishing. Our joy at discovering it, however, was short-lived. We had scarcely quenched our thirst when we saw, to our dismay, a large band of Indians camped on its banks. Their furtive glances at us and significant looks at each other aroused our worst suspicions, and we instinctively felt we were not to get away without serious trouble. Contrary to our expectations, however, they did not offer to molest us, and we at once made up our minds they preferred to wait for our return, as we believed they had somehow learned of our intention to bring back from New Mexico a large herd of mules and ponies.

We arrived in Santa Fe on July 20 without further adventure, and after having our stock of goods passed through the customs house, we were granted the privilege of selling them. The majority of the party sold out quickly and started on their road to the States, leaving 21 of us behind to return later.

On September 1, those who had remained in Santa Fe commenced our homeward journey. We started with 150 mules and horses, four wagons, and a large amount of silver coin. Nothing of an eventful character occurred until we arrived at the Upper Cimarron Springs, where we intended to encamp for the night. But, our anticipations of peaceful repose were rudely dispelled, for when we rode up on the summit of the hill, the sight that met our eyes was appalling enough to excite the gravest apprehensions. It was a large camp of Comanche, evidently there for robbery and murder. We could neither turn back nor go on either side of them on account of the mountainous character of the country, and we realized, when too late, that we were in a trap.

There was only one road open to us, and that was right through the camp. Assuming the bravest look possible and keeping our rifles in position for immediate action, we started on the perilous venture. The chief met us with a smile of welcome and said, in Spanish, “You must stay with us tonight. Our young men will guard your stock, and we have plenty of buffalo meat.”

Realizing the danger of our situation, we took advantage of every moment to hurry through their camp. Captain Means, Ellison, and I were a little distance behind the wagons on horseback. Observing that the balance of our men was evading them, the bloodthirsty Indians at once threw off their masks of dissimulation, and in an instant, we knew the time for a struggle had arrived.

The Indians, as we rode on, seized our bridle-reins and began to fire upon us. Ellison and I put spurs to our horses and got away, but Captain Means, a brave man, was ruthlessly shot and cruelly scalped while the life-blood was pouring from his ghastly wounds.

We succeeded in fighting them off until we had left their camp half a mile behind, and as darkness had settled down on us, we decided to go into camp ourselves. We tied our gray bell-mare to a stake and went out and jingled the bell whenever any of us could do so, thus keeping the animals from stampeding. We corralled our wagons for better protection, and the Indians kept us busy all night resisting their furious charges. We all knew that death at our posts would be infinitely preferable to falling into their hands, so we resolved to sell our lives as dearly as possible.

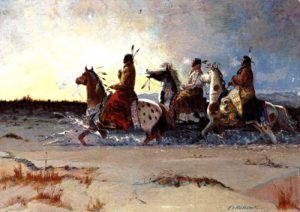

Comanche Indians.

The next day, we made only five miles; it was a continuous fight and a very difficult matter to prevent their capture. This annoyance continued for four days; they would surround us, then let up as if taking time to renew their strength, to charge upon us again suddenly, and they continued to harass us until we were almost exhausted from loss of sleep.

After leaving the Cimarron River, we emerged on the open plains and flattered ourselves we were well rid of the Indians. But about noon, they came down on us again, uttering their demoniacal yells, which frightened our horses and mules so terribly that we lost every hoof. When trying to recapture some of the stolen stock, a member of our party named Hitt was taken by the Indians but luckily escaped from their clutches after having been wounded in 16 parts of his body; he was shot, tomahawked, and speared.

When the painted demons saw that one of their numbers had been killed by us, they left the field for a time, while we, taking advantage of the temporary lull, went back to our wagons and built breastworks of them, the harness, and saddles. From noon until two hours in the night, when the moon went down, the Indians were confident we would soon fall prey to them, and they made charge after charge upon our rude fortifications.

Darkness was now upon us. There were two alternatives before us: should we resolve to die where we were or attempt to escape in the black hours of the night? It was a desperate situation. Our little band looked the matter squarely in the face, and, after a council of war had been held, we determined to escape if possible.

To carry out our resolve, it was necessary to abandon the wagons, together with a large amount of silver coin, as it would be impossible to take all of the precious stuff with us in our flight; so we packed up as much of it as we could carry, and, bidding our hard-earned wealth a reluctant farewell, stepped out in the darkness like specters and hurried away from the scene of death.

Arkansas River.

Our proper course was easterly, but we went northerly to avoid the Indians. We traveled all that night, the next day, and a portion of its night until we reached the Arkansas River, and, having eaten nothing during that whole time excepting a few prickly-pears, were beginning to feel weak from the weight of our burdens and exhaustion. At this point, we decided to lighten our loads by burying all of the money we had carried thus far, keeping only a small sum for each man. Proceeding to a small island in the river, our treasure was cached in the ground between two cottonwood trees, amounting to over 10,000 silver dollars.

Believing now that we were out of the usual range of the predatory Indians, we shot a buffalo and an antelope, which we cooked and ate without salt or bread, but no meal has ever tasted better to me than that one. We continued our journey northward for three or four days more. When we reached Pawnee Fork, we traveled down it for more than a week, arriving again on the Old Santa Fe Trail. Following the trail for three days, we arrived at Walnut Creek, then left the river again and went eastward to Cow Creek.

When we reached that point, we had become so completely exhausted and worn out from subsisting on buffalo meat alone that it seemed as if there was nothing left for us to do but lie down and die. Finally, it was determined to send five of the best-preserved men on ahead to Independence, Missouri — 200 miles ahead, to procure assistance; the other 15 to get along as well as they could until assistance reached them.

I was one of the five selected to go on in advance, and I shall never forget the terrible suffering we endured. We had no blankets, and it was getting late in the fall. Some of us were entirely barefooted, and our feet so sore that we left stains of blood at every step. Deafness, too, seized upon us so intensely, occasioned by our weak condition, that we could not hear the report of a gun fired at a distance of only a few feet.

Two of our men laid down their arms at one place, declaring they could carry them no farther and would die if they did not get water. We left them and went in search of some. After following a dry branch several miles, we found a muddy puddle from which we succeeded in getting half a bucket full, and, although black and thick, it was life for us, and we guarded it with jealous eyes. We returned to our comrades about daylight, and the water so refreshed them they were able to resume the weary march. We traveled until we arrived at the Big Blue River in Missouri; on the bank, we discovered a cabin about 15 miles from Independence. The occupants of the rude shanty were women, seemingly very poor, but they freely offered us a pot of pumpkin they were stewing. When they first saw us, they were frightened because we looked more like skeletons than living beings. They jumped on the bed while we were greedily devouring the pumpkin, but we had to refuse some salt meat which they had also proffered, as our teeth were too sore to eat it. Two men came to the cabin and took three of our men home with them in a short time. We had subsisted for 11 days on one turkey, a coon, a crow, and some elm bark, with an occasional bunch of wild grapes, and the pictures we presented to these good people they will never, probably, forget; we had not tasted bread or salt for 32 days.

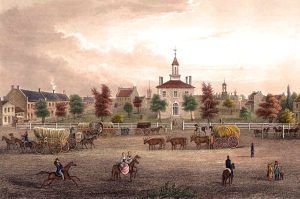

Independence, Missouri Square, 1855.

Our newly found friends secured horses and guided us to Independence the next day, all riding without saddles. One of the party had gone on to notify the citizens of our safety, and when we arrived, general muster was going on, the town was crowded, and when the people looked upon us, the most intense excitement prevailed. All business was suspended; the entire population flocked around us to hear the remarkable story of our adventures and to render us the assistance we so much needed. We were half-naked, foot-sore, and haggard, presenting such a bleak picture that immediately aroused the greatest sympathy on our behalf.

We then said that 15 comrades were struggling toward Independence behind us on the trail somewhere or were already dead from their sufferings. In a very few minutes, seven men with 15 horses started out to rescue them.

They were gone from Independence for several days but had the good fortune to find all the men just in time to save them from starvation and exhaustion. Two were discovered 100 miles from Independence, and the remainder scattered along the Trail 50 miles further in their rear.

Not more than two of the unfortunate parties were together. The humane rescuers seemingly brought back nothing but living skeletons wrapped in rags, but the good people of the place vied with each other in their attention. Under their watchful care, the sufferers rapidly recuperated.

One would suppose that we had had enough of the great plains after our first trip; not so, however, for in the spring, we started again on the same journey. Major Riley, with four companies of regular soldiers, was detailed to escort the Santa Fe traders’ caravans to the boundary line between the United States and Mexico, and we went along to recover the money we had buried. The command had been ordered to remain in camp to await our return until October 20.

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

We left Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, about May 10 and soon on the plains. Many troops had never seen any buffalo before and found great sport in wantonly slaughtering them.

At Walnut Creek, we halted to secure a cannon thrown into that stream two seasons previously and succeeded in dragging it out. With a seine made of brush and grapevine, we caught more fine fish than we could dispose of. One morning, the camp was thrown into the greatest state of excitement by a band of Indians running an enormous herd of buffalo right into us.

The troops fired at them by platoons, killing hundreds of them. We marched in two columns and formed a hollow square at night when we camped, in which all slept excepting those on guard duty. Frequently, someone would discover a rattlesnake or a horned toad in bed with him, and it did not take him a very long time to crawl out of his blankets!

On July 10, we arrived at the dividing line separating the two countries and went into camp. The next day, Major Riley sent a squad of soldiers to escort me and another of our old party, who had helped bury the $10,000, to find it. A few miles further up the Arkansas River than our camp, in the Mexican limits. When we reached the memorable spot on the island, we found the coin safe, but the water had washed the earth away, and the silver was exposed to view to excite the cupidity of anyone passing that way. However, there were not many travelers on that lonely route in those days, and it would have been just as secure, probably, had we poured it on the ground. We put the money in sacks and deposited it with Major Riley. After leaving the camp, we started for Santa Fe with Captain Bent as the leader of the traders. We had not proceeded far when our advanced guard met Indians. They turned, and when within 200 yards of us, one man named Samuel Lamme was killed, his body being completely riddled with arrows. His head was cut off, and all his clothes were stripped from his body. We had a cannon, but the Mexicans who hauled it had tied it up in such a way that it could not be utilized in time to affect anything in the first assault; but when at last it was turned loose upon the Indians, they fled in dismay at the terrible noise.

The troops at the crossing of the Arkansas River, hearing the firing, came to our assistance. The next morning, the hills were covered by 2,000 Indians, who had congregated there to annihilate us, and the coming of the soldiers was indeed fortunate, for as soon as the Indians discovered them, they fled. Major Riley accompanied us on our march for a few days, and seeing no more Indians, he returned to his camp.

We traveled for a week and then met 100 Mexicans who were out on the plains hunting buffalo. They had killed a great many and were drying the meat. We waited until they were ready to return, and then we all started for Santa Fe together.

Rabbit Ears, New Mexico by Kathy Alexander.

At Rabbit-Ear Mountain, the Indians had constructed breastworks in the brush to fight it out there. The Mexicans were in the advance and killed one of their number before discovering the enemy. We passed Point of Rocks and camped on the river. One of the Mexicans went out hunting and shot a huge panther; the next morning, he asked a companion to go with him and help skin the animal. They saw the Indians in the brush, and the one who had killed the panther said to the other, “Now for the mountains,” but his comrade retreated and was dispatched by the Indians almost within reach of the column.

We now decided to change our destination, intending to go to Taos, New Mexico, instead of Santa Fe. However, the governor of the Province sent out troops to stop us, as Taos was not a place of entry. The soldiers remained with us a whole week until we arrived in Santa Fe, where we disposed of our goods and soon began to prepare for our return trip.

When we were ready to start back, seven priests and several wealthy families accompanied us comfortably fixed in carriages. The Mexican government ordered Colonel Viscarra of the army, with five cavalry troops, to guard us to the camp of Major Riley.

We experienced no trouble until we arrived at the Cimarron River. About sunset, just as we were preparing to camp for the night, the sentinels saw a body of 100 Indians approaching; they fired at them and ran to camp. Knowing they had been discovered, the Indians came on and made friendly overtures. Still, the Pueblo Indians who were with the command of Colonel Viscarra wanted to fight them at once, saying the fellows meant mischief. We declined to camp with them unless they would agree to give up their arms; they pretended they were willing to do so when one of them put his gun at the breast of our interpreter and pulled the trigger. In an instant, a bloody scene ensued; several of Viscarra’s men were killed, together with several mules. Finally, the Indians were whipped and tried to get away, but we chased them some distance and killed 35.

Our friendly Puebloans were delighted and proceeded to scalp the Indians, hanging the bloody trophies on the points of their spears. That night, they indulged in a war dance, which lasted until nearly morning.

We were delighted to see a beautiful sunshiny day after the horrors of the preceding night. We continued our march without further interruption, safely arriving at the camp on the boundary line, where Major Riley was waiting for us, as we supposed. Still, his time having expired the day before, he had left for Fort Leavenworth. However, a courier was despatched to him as Colonel Viscarra desired to meet the American commander and see his troops. The courier overtook Major Riley a short distance away, and he halted for us to come up. Both commands then went into camp and spent several days comparing the discipline of the two nations’ armies and having a generally good time. Colonel Viscarra greatly admired our small arms and took his leave in a very courteous manner.

Fort Leavenworth, 1867.

We arrived at Fort Leavenworth late in the season, and from there, we all scattered. I received my share of the money we had cached on the island and bade my comrades farewell, only a few of whom I have ever seen since.

Mr. Hitt, in his notes of this same perilous trip, said:

When the grass had sufficiently started to ensure the subsistence of our teams, our wagons were loaded with a miscellaneous assortment of merchandise, and the first trader’s caravan of wagons that ever crossed the plains left Independence. Before we traveled for three weeks on our journey, we were one evening confronted with the novel fact of camping in a country where no stick of wood could be found. The grass was too green to burn, and we were wondering how our fire could be started with which to boil our coffee or cook our bread. One of our number, however, while diligently searching for something to utilize, suddenly discovered scattered all around him a large number of buffalo chips, and he soon had an excellent fire underway, his coffee boiling and his bacon sizzling over the glowing coals.

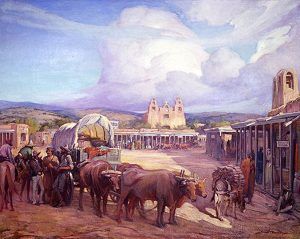

The End of the Santa Fe Trail by Gerald Cassidy, about 1910

We arrived in Santa Fe without incident, and as ours was the first train of wagons that ever traversed the narrow streets of the quaint old town, it was, of course, a great curiosity to the natives.

After a few days’ rest, sightseeing, and purchasing stock to replace our tired animals, preparations were made for the return trip. All the money we had received for our goods was in gold and silver, principally the latter, in consequence of which, each member of the company had about as much as he could conveniently manage, and, as events turned out, much more than he could take care of.

On the morning of the third day out, when we were not looking for the least trouble, our entire herd was stampeded, and we were left upon the prairie without as much as a single mule to pursue the fast-fleeing thieves. The Mexicans and Indians had come so suddenly upon us and had made such an effective dash that we stood like children who had broken their toys on a stone at their feet. We were so unprepared for such a stampede that the thieves did not approach within rifle-shot range of the camp to accomplish their objective, few of them coming within sight, even.

After the excitement had somewhat subsided, and we began to realize what had been done, it was decided that while some should remain to guard the camp, others must go to Santa Fe to see if they could not recover the stock. The party that went to Santa Fe had no difficulty recognizing the stolen animals, but when they claimed them, they were laughed at by the officials. However, they experienced no difficulty in purchasing the same stock for a small sum, which they at once did, and hurried back to camp. By this unpleasant episode, we learned of the stealth and treachery of the miserable people in whose country we were. We, therefore, took every precaution to prevent a repetition of the affair and kept up a vigilant guard night and day.

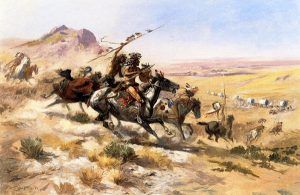

Indian attack on a wagon train by Charles Marion Russell.

Matters progressed very well, and when we traveled some 300 miles eastward, thinking we were out of range of any predatory bands, as we had seen no sign of any living thing, we relaxed our vigilance somewhat. One morning, just before dawn, the whole earth seemed to resound with the most horrible noises that ever greeted human ears; every blade of grass appeared to re-echo the horrid din. In a few moments, every man was at his post, rifle in hand, ready for any emergency, and almost immediately, a large band of Indians made their appearance, riding within rifle-shot of the wagons. A continuous battle raged for several hours, the Indians discharging a shot, then scampering off out of range as fast as their ponies could carry them. Some, braver than others, would venture closer to the corral, and one of these got the contents of an old-fashioned flintlock musket in his bowels.

We were careful not to fire at the same time, and several of our party, who were watching the effects of our shots, declared they could see the dust fly out of the robes of the Indians as the bullets struck them. It was learned afterward that a number of the Indians were wounded and that several had died. Many were armed with bows and arrows only, and to execute, they were obliged to come near the corral. The Indians soon discovered they were getting the worst of the fight and, having run off all the stock, abandoned the conflict, leaving us in possession of the camp, but it can hardly be said masters of the situation.

There we were, 35 pioneers upon the wild prairie, surrounded by a wily and cruel foe, without transportation of any character but our legs, and with 500 miles of dangerous, trackless waste between us and the settlements. We had an abundance of money, but the stuff was worthless for the present, as there was nothing we could buy with it.

After the last Indian had ridden away into the sandhills on the opposite side of the river, each one of us had a thrilling story to relate of his narrow escapes. Though none were killed, many received wounds, the scars they carried through life. I was wounded six times. Once was in the thigh by an arrow, and once while loading my rifle, I had my ramrod shot off close to the muzzle of my piece, the ball just grazing my shoulder, tearing away a small portion of the skin. Others had equally curious experiences, but none were seriously injured.

After the excitement of the battle had subsided, the realization of our condition fully dawned upon us. When we were first robbed, we were only a short distance from Santa Fe, where our money could easily procure other stock; now, there were 300 miles behind us to that place, and the picture was anything but pleasant to contemplate.

To transport supplies for 35 men seemed impossible. Our money was now a burden greater than we could bear; what was to be done with it? We would have no use for it on our way to the settlements, yet the idea of abandoning it seemed hard to accept. A vigilant guard was kept up that day and night, during which time we all remained in the camp, fearing a renewal of the attack.

The next morning, as there were no apparent signs of the Indians, it was decided to inspect the surrounding country in the hope of recovering a portion, at least, of our lost stock, which we thought might have become separated from the main herd. Three men were detailed to stay in the old camp to guard it while the remainder, in squads, scoured the hills and ravines. Not a horse or mule was visible anywhere; the stampede had been complete–not even the direction the animals had taken could be discovered.

Indian Attack by Frederic Remington, 1907.

It was late in the afternoon when I, having left my companions to continue the search and returning to camp alone, had gotten within a mile of it that I thought I saw a horse feeding upon an adjoining hill. I at once turned my steps in that direction and had proceeded but a short distance when three Indians jumped from their ambush in the grass between me and the wagons and ran after me. The men in camp had been watching my every movement, and as soon as they saw the Indians were chasing me, they started in pursuit, running at their greatest speed to my rescue.

The Indians soon overtook me, and the first one that came up tackled me but in an instant found himself flat and shared the same fate. By this time, the third one arrived, and the two I had thrown grabbed me by the legs so that I could no longer handle myself, while the third one had a comparatively easy task in pushing me over. Fortunately, my head fell toward the camp and my fast-approaching comrades. The two Indians held my legs to prevent my rising, while the third one, who was standing over me, drew from his belt a tomahawk, and shrugging his head in his blanket, at the same time looking over his shoulder at my friends, with a tremendous effort and that peculiar grunt of all Indians, plunged his hatchet, as he supposed, into my head. Still, instead of scuffling to free myself and rise to my feet, I merely turned my head to one side, and the wicked weapon was buried in the ground, just grazing my ear.

Three mounted Comanche warriors, 1892.

The Indian, seeing that he had missed, raised his hatchet and once more, shrugging his head in his blanket, and turning to look over his other shoulder, attempted to strike again, but the blow was evaded by a sudden toss of his intended victim’s head. Not satisfied with two abortive trials, the third attempt must be made to brain me, and repeating the same motions, with a great “Ugh!” he seemed to put all his strength into the blow, which, like the others, missed and spent its force in the earth. By this time, the rescuing party had come near enough to prevent the savage from risking another effort. He then addressed the other Indians in Spanish, which I understood, saying, “We must run, or the Americans will kill us!” and loosening his grasp, he scampered off with his companions as fast as his legs could take him, hurried on by several pieces of lead fired from the old flintlocks of the traders.

By sundown, every man had returned to the desolate camp, but not an animal had been recovered. Then, with tired limbs and weary hearts, we took turns guarding the wagons through the long night. The next morning, each man shouldered his rifle. Having had his proportion of the provisions and cooking utensils assigned him, we broke camp and again turned to take a last look at the country behind us, in which we had experienced so much misfortune, and started on foot for our long march through the dangerous region ahead of us.

Scarcely had we gotten out of sight of our abandoned camp, when one of the party, happening to turn his eyes in that direction, saw a large volume of smoke rising in the vicinity; then we knew that all of our wagons, and everything we had been forced to leave, were burning up. This proved that, although we had been unable to discover any signs of Indians, they had been lurking around us all the time, and this fact warned us to exercise the utmost vigilance in guarding our persons.

Though our burdens were very heavy, the first few days were passed without anything to relieve the dreadful monotony of our wearisome march. Still, each succeeding 24 hours, our loads became visibly lighter, as our supplies were rapidly diminishing. It had already become apparent that even in the exercise of the greatest frugality, our stock of provisions would not last until we could reach the settlements, so some of the most expert shots were selected to hunt for game. Still, even in this, they were not successful, the very birds seeming to have abandoned the country in its extreme desolation.

After eight days of travel, despite our most rigid economy, an inventory showed that less than 100 pounds of flour were left. The hunters repeated the same old story day after day: “No game!” For two weeks, each individual was allowed only a spoonful, stirred in water, and taken three times a day.

Hunter.

However, fortune smiled upon the weary party; one of the hunters returned to camp with a turkey he had killed. It was soon broiling over a fire that willing hands had kindled, and our drooping spirits were revived for a while. While the turkey was cooking, a crow flew over the camp, and one of the company, seizing a gun, dispatched it. In a few moments, it, too, was sizzling along with the other bird.

Now, in addition to the pangs of hunger, a scarcity of water confronted us, and one day we were compelled to resort to a buffalo-wallow and suck the moist clay where the huge animals had been stamping in the mud. We were much reduced in strength, yet each day added new difficulties to our sad situation. Some became so weak and exhausted that it was with the greatest effort they could travel at all. To divide the company and leave the more feeble behind to starve or be murdered by the merciless Indians was not considered for a moment. Still, one alternative remained, and that was speedily accepted. As soon as a convenient camping ground could be found, a halt was made, shelter established, and things made as comfortable as possible. Here, the weakest remained to rest while some of the strongest scoured the surrounding country searching for game. During this temporary halt, the hunters were more successful than before, having killed two buffaloes in one morning, along with some smaller animals. Again, the dry natural fuel of the prairies was called into requisition, and a juicy steak was once more broiling over the fire.

With an abundance to eat and a few days’ rest, the whole company revived and was enabled to renew their march homeward. We were now in the buffalo range. Every day, the hunters were fortunate enough to kill one or more of the immense animals, thus keeping our larder in excellent condition and avoiding starvation.

Doubting whether our good fortune concerning food would continue for the remainder of our march and our money becoming very cumbersome, it was decided by a majority that at the first suitable place we came to, we would bury it and risk its being stolen by our enemies. When not more than half of our journey had been accomplished, we came to an island in the river to which we waded, and there, between two large trees, we dug a hole and deposited our treasure. We replaced the sod over the spot, taking the utmost precaution to conceal every sign of disturbing the ground. Though no Indians had been seen for several days, a sharp lookout was kept in all directions for fear that some lurking savage might have been watching our movements. This task was finished with much lighter burdens, but more anxious than ever, we again took up our march eastwardly and, thus relieved, were able to carry a greater quantity of provisions.

Having journeyed until we supposed we were within a few miles of the settlements, some of our number, scarcely able to travel, thought the best course to pursue would be to divide the company; one portion to press on, the weaker ones to proceed by more manageable stages, and when the advance arrived at the settlements, they were to send back relief for those plodding on wearily behind them. Soon, a few who were stronger than the others reached Independence, Missouri, and immediately sent a party with horses to bring in their comrades; so, at last, all got safely to their homes.

Major Bennett C. Riley.

In the spring of 1829, Major Bennett Riley of the United States Army was ordered with four companies of the Sixth Regular Infantry to march out on the Trail as the first military escort ever sent to protect the caravans of traders going and returning between Western Missouri and Santa Fe. Captain Philip St. George Cooke of the Dragoons accompanied the command and kept a faithful journal of the trip. The official report of Major Riley to the Secretary of War, I have interpolated here copious extracts.

The journal of Captain Cooke states that the battalion marched from Fort Leavenworth, which was then called a cantonment, and, strange to say, had been abandoned by the Third Infantry on account of its unhealthiness. On June 5, Riley crossed the Missouri River, the cantonment, and re-crossed the river again at a point a little above Independence to avoid the Kansas River, which had no ferry.

After five days’ marching, the command arrived at Round Grove, where the caravan had been ordered to rendezvous and wait for the escort. The number of traders aggregated about seventy-nine men, and their train consisted of 38 wagons drawn by mules and horses, the former preponderating. At an average of 14 miles a day, five days’ marching brought them to Council Grove. Leaving the Grove, in a short time, Cow Creek was reached, which at that date abounded in fish, many of which, says the journal, “weighed several pounds, and were caught as fast as the line could be handled.” The captain does not describe the variety to which he refers; probably they were the buffalo–a species of sucker, to be found today in every considerable stream in Kansas.

Having reached the Upper Valley, bordered by high sandhills, the journal continues:

Buffalo on the Great Plains.

From the tops of the hills, we saw far away, in almost every direction, mile after mile of prairie, blackened with buffalo. One morning, when our march was along the natural meadows by the river, we passed through them for miles; they opened in front and closed continually in the rear, preserving a distance scarcely over 300 paces. On one occasion, a bull had approached within 200 yards without seeing us until he ascended the river bank; he stood a moment shaking his head and then charged at the column. Several officers stepped out and fired at him, and two or three dogs also rushed to meet him. Still, right onward he came, snorting blood from mouth and nostril at every leap, and, with the speed of a horse and the momentum of a locomotive, dashed between two wagons, which the frightened oxen nearly upset; the dogs were at his heels, and soon he came to bay, and, with tail erect, kicked violently for a moment, and then sank in death–the muscles retaining the dying rigidity of tension.

The command arrived at its destination–Chouteau’s Island, then on the boundary line between the United States and New Mexico about the middle of July. Our orders were to march no further, and, as a protection to the trade, it was like the establishment of a ferry to the mid-channel of a river.

Santa Fe Trail Freighters.

Up to this time, traders had always used mules or horses. Our oxen were an experiment that succeeded admirably; they even did better when water was very scarce, which is an important consideration.

A few hours after the departure of the trading company, as we enjoyed a quiet rest on a hot afternoon, we saw several horsemen riding furiously toward our camp beyond the river. We all flocked out of the tents to hear the news, for they were soon recognized as traders. They stated that the caravan had been attacked, about six miles off in the sandhills, by an innumerable host of Indians; that some of their companions had been killed; and they had run, of course, for help. There was not a moment’s hesitation; the word was given, and the tents vanished as if by magic. The oxen grazing nearby were speedily yoked to the wagons, and we marched into the river. Then I deemed myself the most unlucky of men; a day or two before, while eating my breakfast, with my coffee in a tin cup–notorious among chemists and campaigners for keeping it hot–it was upset into my shoe, and on pulling off the stocking, it so happened that the skin came with it. Being thus hors de combat, I sought to enter the combat on a horse, which was allowed, but I was put in command of the rear guard to bring up the baggage train. It grew late, and the wagons crossed slowly, for the river unluckily took that particular time to rise fast, and, before all were over, we had to swim it, and by moonlight. We reached the encampment at one o’clock at night. All was quiet and remained so until dawn, when the pickets reported they saw several Indians moving off at the sound of our bugles. On looking around us, we perceived ourselves and the caravan in the most unfavorable defenseless situation possible–in the feet high and within gun-shot all around. There was the narrowest practicable entrance and outlet.

We ascertained that some mounted traders, despite all remonstrance and command, had ridden on in advance, and when in the narrow pass beyond this spot, had been suddenly beset by about 50 Indians; all fled and escaped save one, who, mounted on a mule, was abandoned by his companions, overtaken, and slain. The Indians, perhaps, equaled the traders in number, but notwithstanding their extraordinary advantage of the ground, dared not attack them when they made a stand among their wagons; and the latter, all well armed, were afraid to make a single charge, which would have scattered their enemies like sheep.

Having buried the poor fellow’s body and killed an ox for breakfast, we left this sand hollow, which would soon have been roasting hot, and advancing through the defile–of which we took care to occupy the commanding ground–proceeded to escort the traders at least one day’s march further.

Freighting.

When the next morning broke clear and cloudless, the command was confronted by one of those terrible hot winds, still frequent on the plains. The oxen with lolling tongues were incapable of going on; the train was halted, and the suffering animals unyoked, but they stood motionless, making no attempt to graze. Late that afternoon, the caravan pushed on for about 10 miles, where was the sandy bed of a dry creek, and fortunately, not far from the Trail, up the stream, a pool of water and an acre or two of grass was discovered. On the water’s surface floated thick the dead bodies of small fish, which the intense heat of the sun that day had killed.

Arriving at this point, it was determined to march no further into the Mexican territory. At the first light next day, we were in motion to return to the river and the American line, and no further adventure befell us.

While permanently encamped at Chouteau’s Island, situated in the Arkansas River, the term of enlistment of four of the soldiers of Captain Cooke’s command expired, and they were discharged. In his journal, he says:

Contrary to all advice, they determined to return to Missouri. After having marched several hundred miles over a prairie country, being often on high hills commanding a vast prospect, without seeing a human being or a sign of one, and, save the trail we followed, not the slightest indication that man had ever visited the country, it was exceedingly difficult to credit that lurking foes were around us, and spying our motions. It was so with these men, and being armed, they set out on August 1 on foot for the settlements. That same night, three of the four returned. They reported that, after walking about 15 miles, they were surrounded by 30 mounted Indians. A wary old soldier of their number succeeded in extricating them before any hostile act had been committed. Still, one of them, highly elated and pleased at their forbearance, insisted on returning among them to give them tobacco and shake hands. In this friendly act, he was shot down. The Indians stripped him in an incredibly short time and as quickly dispersed to avoid a shot, and the old soldier, after cautioning the others to reserve their fire, fired among them and probably with some effect. Had the others done the same, the Indians would have rushed upon them before they could have reloaded. They managed to make good their retreat in safety to our camp.

We were instructed to wait here for the return of the caravan, which was expected early in October. Our provisions consisted of salt and half rations of flour, besides a reserve of 15 days’ full rations–as to the rest, we were dependent upon hunting. When the buffalo became scarce or the grass bad, we marched to other ground, thus roving up and down the river for eighty miles. The first thing we did after camping was to dig and construct, with flour barrels, a well in front of each company; water was always found at the depth of from two to four feet varying with the corresponding height of the river, but clear and cool. Next, we would build sod fire-places; these, with network platforms of buffalo hide, used for smoking and drying meat, formed a tolerable additional defense, at least against mounted men.

Hunting was a military duty, done by detail, with parties of 15 or 20 going out in wagons. Completely isolated and beyond support or even communication, in the midst of many thousands of Indians, the utmost vigilance was maintained. As the guard officer every fourth night, I was always awake and generally in motion the whole time of duty. Night alarms were frequent; when, as we all slept in our clothes, we were accustomed to assembling instantly, and with scarcely a word spoken, take our places in the grass in front of each face of the camp, where, however wet, we sometimes lay for hours.

Indian smoke signal.

While encamped a few miles below Chouteau’s Island, on August 11, an alarm was given, and we were under arms for an hour until daylight. During the morning, Indians were seen a mile or two off, leading their horses through the ravines. A captain, however, with 18 men, was sent across the river after buffalo, which we saw half a mile distant. In his absence, a large body of Indians came galloping down the river as if to charge the camp, but the cattle were secured in good time. A company of which I was lieutenant was ordered to cross the river and support the first. We waded in some disorder through the quick-sands and current, and just as we neared a dry sandbar in the middle, a volley was fired at us by a band of Indians, who that moment rode to the water’s edge. The balls whistled very near, but without damage; I felt an involuntary twitch of the neck, and wishing to return the compliment instantly, I stooped down, and the company fired over my head, with what execution was not perceived, as the Indians immediately retired out of our view. This had passed in half a minute, and we were astonished to see, a little above, among some bushes on the same bar, the party we had been sent to support, and we heard that they had abandoned one of the hunters, who had been killed. We then saw, on the bank we had just left, a formidable body of the enemy in close order, and hoping to surprise them, we ascended the bed of the river. In crossing the channel, we were up to the armpits, but when we emerged on the bank, we found that the Indians had detected the movement and retreated. Casting eyes beyond the river, I saw a number of the Indians riding on both sides of a wagon and team that had been deserted, urging the animals rapidly toward the hills. At this juncture, the adjutant sent an order to cross and recover the body of the slain hunter, who was an old soldier and a favorite. He was brought in with an arrow still transfixing his breast, but his scalp was gone.

On October 14, we again marched on our return. Soon after, we saw smoke rise over the distant hills; evidently, signals, indicating to different parties of Indians our separation and march, but whether preparatory to an attack upon the Mexicans or ourselves or rather our immense drove of animals, we could only guess.

Our march was constantly attended by significant collections of buffalo, which seemed to have a general muster, perhaps for migration. Sometimes a hundred or two–a fragment from the multitude–would approach within two or 300 yards of the column and threaten a charge which would have proved disastrous to the mules and their drivers.

Under the friendly cover of the shades of evening, on November 8, our ragged veterans marched into Fort Leavenworth. They took quiet possession of the miserable huts and sheds left by the Third Infantry in the preceding May.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2025.

Also See:

Famous Men of the Santa Fe Trail

Indian Terrors on the Santa Fe Trail

Santa Fe Trail – Highway to the Southwest

About the Author: Excerpted from the book, The Old Santa Fe Trail, by Colonel Henry Inman, 1897. Note: The text is not verbatim, as minor edits have been made throughout the tale. Henry Inman was well known both as an officer in the U.S. Army and an author dealing with subjects of the Western plains. During the Civil War, Inman was a Lieutenant Colonel, and afterward, he won distinction as a magazine writer. He wrote several books, including his Old Santa Fe Trail, Great Salt Lake Trail, The Ranch on the Ox-hide, and other similar books dealing with the subjects he knew so well. Colonel Inman left a number of unfinished manuscripts at his death in Topeka, Kansas, on November 13, 1899.