The Santa Fe Trail and the Railroad: 1865-1880 – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad

The importance of the period of railroad expansion westward along the course of the Santa Fe Trail from its eastern terminus in 1865 to its arrival in Santa Fe in 1880 lies in the fact that it witnessed the change in the character of overland trade along the Trail. By 1865, territorial and state boundaries had become more formalized and would soon be further refined to provide the basis for the continued formation of the United States.

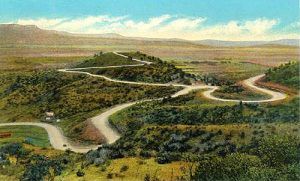

Although the Mountain Route of the Santa Fe Trail had been in common use since the 1840s, its terrain provided many obstacles to wagon movement. One such obstacle was the tortuous 8,000-foot, axle-breaking Raton Pass. The Raton Mountains themselves were a series of high mesas, separated by narrow, precipitous canyons, adjoining the Sangre de Cristo Mountains at right angles and extending eastward for over 100 miles along what is now the Colorado–New Mexico border. Raton Pass was by no means the only route over this mountainous terrain. There was another route west of it and four routes to its east — San Francisco Pass, Manco de Burro Pass, Trinchera Pass, and Emery Gap, which could accommodate the passage of traders. Some of these routes remained difficult, if not impassable, for wagons. Recorded use of Raton Pass as an avenue of communication dates back to the early 18th century when Ulibarri (1706), Valverde (1719), and probably Villasur (1720) en route from Santa Fe via Taos went over the Taos-Palo Flechado Pass through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains onto the plains of northeastern New Mexico and from there, through Raton Pass into southeastern Colorado.” Antonio Valverde y Cosio, Governor of New Mexico, who led an expedition through Raton Pass in 1719, documented the difficulties of that route.

Richens “Uncle Dick” Wooten

In 1865, Richens Lacy “Uncle Dick” Wootton assembled a group of Mexican laborers and commenced work on blasting overhangs and hairpin curves of the Trail at Raton Pass. Wootton had obtained charters from the Colorado and New Mexico legislatures to build a toll road over Raton Pass from Trinidad to the Red (Canadian) River. Upon completion of the work in that year, a toll road was opened, allowing wagons easier access to the Mountain Route. This venture proved to be extremely profitable, with in excess of 5,000 wagons using the toll road in 1866. In a single one-year, three-month, and nine-day period in the 1860s, Wootton made $9,163.64 on receipts alone. The Sangre de Cristo Pass fell into disuse, while Wootton’s road became the principal artery between Colorado and New Mexico until the coming of the railroad.

On September 21, 1865, the first train arrived in Kansas City over the Missouri Pacific Railroad. Even though individuals left Kansas City for Santa Fe as late as 1868, the last wagon trains left Kansas City in the spring of 1866. As the eastern terminus of the Trail moved westward, former locations on the Santa Fe Trail that relied on the influx of traders and trading suffered. On August 31, 1867, the Junction City Union reported:

“A few years ago, the freighting wagons and oxen passing through Council Grove were counted by thousands, the value of merchandise by millions. But the shriek of the iron horse has silenced the lowing of the panting ox, and the old trail looks desolate.”

Raton Pass, New Mexico

The Kansas Pacific Railroad (formerly the Union Pacific Railroad, Eastern Division) and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad shortened the Trail as their steel rails raced for Santa Fe: Sheridan (May 1868); Burlingame (September 1868); Cheyenne Wells (March 1870); Kit Carson (March 1870); Emporia (summer, 1870); Newton (July 1871); Hutchinson (June 1872), Great Bend (July 1872); and Larned, Kansas (August 1872). In 1878, Wootton sold out his toll road through Raton Pass to the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad.

From before the Civil War and even after the arrival of the railroad, military freighting remained an important activity along the Santa Fe Trail. Since much of the military freighting that did take place was fulfilled by civilian contractors, this activity also presented the opportunity for military-civilian interaction. Despite the delivery delays and damage of military freight, the transportation system that allowed for civilian contractors proved to be cheaper and more manageable than providing government trains. The lack of success of government freighting experienced during the Mexican-American War prompted the government to experiment with contract freighting. The relative success of these civilian contracts resulted in more of them being awarded to serve the increasing number of military outposts that were developing along the Trail. As the competition among civilian contractors increased, the cost of transportation of military supplies decreased. However, transported items still increased up to five or six times their original value when transportation costs were included. The provision of a military escort and the westward advance of the Kansas Pacific Railroad in the late 1860s witnessed a decrease in the uncertainty, the length of time, and the expense of military freighting. In the 1870s, the principal Arms handling military freight for New Mexico were Otero, Sellar and Company, and Chick, Browne, and Company. As the railroad continued its westward advance to Santa Fe, these competing freight companies followed them. When the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad finally reached the western terminus of the Trail in 1880, transportation costs declined, and wagon hauls grew shorter. Railroad transportation allowed for faster, more frequent shipment of supplies, resulting in less spoilage, loss, and deterioration of goods often characteristic of long wagon hauls.

The effect of the railroad on the overland Santa Fe trade is reflected in the repeated shortening of the wagon segments of the Trail. Some traders responded to the impact of the railroad on wagon transport by moving their trading operations westward ahead of the railroad. One such trader was Don Miguel Antonio Otero, who moved the eastern headquarters of his trading operations westward seven times in eleven years from Kansas in 1868 to Las Vegas, New Mexico, in 1879. Since the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad had won the race for the right of way through Raton Pass, it was their trains that were to thunder into Las Vegas on July 4, 1879, and eventually into Santa Fe on February 9, 1880. Soon after this date, wagon use of the Trail as a means of long-distance transportation of goods and individuals proved inefficient, thus closing this chapter in the history of the Santa Fe Trail.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated September 2023.