Vigilantes of California, Idaho, & Montana – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By John W. Clampitt in 1891

Vigilante Notice

In November 1850, there were eight primitive houses situated on the extreme point of a little peninsula far projecting into the Bay of San Francisco. It was separated from the surrounding country by a rocky mountain range. The eight houses were occupied by an American hunter and seven French fishermen, deserters from a French man-of-war. On the opposite side was another French settlement of five fishermen. The only livestock owned by the two settlements was a single goat, the loss of which would have proved a public calamity. Its master had brought it from France, around Cape Horn.

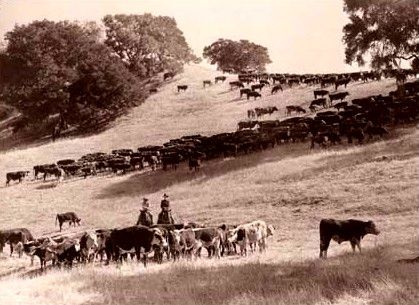

Besides the hunting and fishing people, there was, beyond these settlements, a regular farmer called the Irish Captain, although he was neither Irish nor a captain. He was a Dane by birth and a farmer all his life by occupation. He possessed a valuable stock of imported cattle – a rare thing at that time.

Further into the interior, on the other side of the mountain range, was the Cornelia Rancho, a California manor house constructed of rough beams and surrounded by mud and cattle instead of gardens, parks, green grass, and flowers. Cornelia was a native grandee and claimed the right to 400 square miles of territory. Although the invasion of her country by the gold hunters had swept away the greater part of her herds, there still remained over a thousand head. In full dress, adorned with gold chains, pearls and jewels, she looked magnificent, seated in a large wagon drawn by two oxen and sixteen mules, roughing it over a country without roads. This, however, was upon state occasions and of rare occurrence. Her home dress was an old broad-brimmed straw hat, leather boots, a loose white shirt, and a short petticoat of coarse red flannel. She ruled over 30 Indian servants besides her son, 24 years of age, and a homeless Portuguese adventurer, who was seeking support, had drifted to that Eden before the rude gold hunters dispersed the charm of silence, simplicity, and ignorance that reigned complete everywhere.

The Irish Captain was not slow to perceive his advantage over the senora. He, therefore, proposed to her to take charge of her cattle and sell to the best advantage, on condition that he should have one-half of the sum realized, which proposition was reluctantly accepted by the senora. The Irish Captain now organized for the common defense by calling a general meeting and binding each by a covenant to take care of his neighbors’ property by armed force when necessary. But a short time after that, a boat laden with stolen beef from the senora’s herds was captured, and the cattle thieves were taken prisoners by the Frenchmen of Low Point. The thieves were tied, put under a boat turned upside down, and closely watched. The Irish Captain himself escorted the prisoners to San Francisco the following morning and delivered them into the hands of the civil authorities. Instead of being punished for their lawless crimes, they were set at liberty by the civil authorities and retaliated upon the Irish Captain by butchering and carrying off all his milk cows.

These thieves and this system of robbery received the countenance of wealthy and influential butchers of San Francisco, who furnished the means for these predatory incursions. The money to retain influential counsel to defend and acquit, through technicalities of the law, such of the thieves as should fall into the hands of the Irish Captain and his cohorts.

Convinced that no redress could be obtained from the civil authorities at San Francisco, a second general meeting was held. It was unanimously resolved that the residents of the peninsula should form themselves into a permanent committee and assume all the duties of police and courts-martial. No suspected party should be permitted to land. Thieves and other criminals should be tried before the committee and, if found guilty, executed on the spot. Thus was formed the first Vigilance Committee that ever existed within the limits of California. Three men, who confessed themselves to be Australian convicts, were tried, convicted, and executed by hanging from a tree within a week. Cattle thieves abounded, and retribution swift and sure was meted out whenever the crime could be fixed by the logic of circumstances. Justice and injustice met on a common level.

California Ranch

Small bodies of people took the law into their own hands with the same degree of conscious right as emboldened the acts of two or ten thousand. Sometimes a single individual became at once judge, jury, and executioner. On the highway from San Francisco to San Jose was found a corpse shot through the body, and to the lower buttonhole was tied a placard upon which were written, in very legible characters, these significant words:

I shot him because he stole my mule.

John Andrew Anderson

Anderson Rancho Santa Clara Valley

He was not a murderer but an executor of the law — the unwritten law — against all cattle thieves. If ten men could capture and slay him for the crime, the same right belonged to but one of the party, provided he alone could accomplish it.

Pressed by these vigorous methods, the thieves and robbers in the country retired to the larger towns and settlements to ply their vocation. Popular justice there was neither so swift nor so sure. Public opinion, however, opposed any infringement of the rights and methods of the civil authorities. What five men could do in the country, five hundred could not accomplish in San Francisco or Sacramento.

Sacramento was the first of the large towns to organize a committee of its citizens to protect social order, and its executions became celebrated for the interest displayed in them by the people of the surrounding country. The first of these was at night on the Plaza, in the light of a great fire and in the presence of a great multitude. The office of hangman was conceded as a post of honor to the most reputable and wealthy citizen of the town. Two days after, he paid the penalty of this honor by being himself shot by the desperadoes.

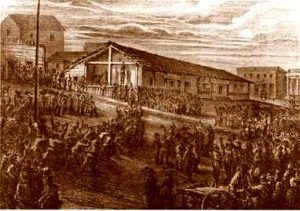

John Jenkins was lynched for stealing about $50 in coins. The Daily Alta California newspaper is just to the left of the cross-like structure where Jenkins hangs.

San Francisco seemed reluctant to begin the exercise of this inherent power of the people. However, the great incendiary fire of May 4, 1851, and the appeals of the Alta California and California Herald, which declared that nothing could disturb the culprits’ equanimity but the extreme measure of banging by the neck, caused a revulsion of feeling, and early in June following two hundred of its most influential citizens formed an association, which they named a Committee of Vigilance, for the maintenance of the peace and good order of society and the preservation of the lives and property of the citizens of San Francisco.

Large placards affixed to the walls in public places of the city and private houses of the citizens, containing the rules and regulations adopted for maintaining the public peace of the city and how public justice should be administered, gave notice of their organization.

The tolling of the bell of the Monumental Fire Engine house on the Plaza was the signal for the members to instantly assemble fully armed.

Thousands of citizens secretly joined the organization, and their services were soon called into requisition. On the evening of June 10, the shipping office of a Mr. Virgin, on the wharf, was robbed of a small safe containing a considerable sum of money. The thief was captured and placed in the custody of members of the Vigilance Committee in their rooms. The property was identified, and the prisoner was convicted on the testimony of the boatman who had pulled out with the prisoner and his booty into the bay, where he was subsequently arrested. The Chief of Police now appeared at the rooms of the committee and demanded admittance and the custody of the prisoner. His request was refused.

After carefully deliberating upon the character of the punishment, it was finally determined that though not a capital offense, the necessity existed for the execution of the criminal and that it should take place at once to prevent a rescue by the friends of the culprit, or an armed interference on the part of the civil authorities. Accordingly, he was notified of his doom and given one hour to prepare for death. Shortly after midnight, the condemned man was taken under a strong guard to Portsmouth Square and hanged to the cross-beams of the gable end of an adobe building that had been used in former times as a post office but was then unoccupied. A coroner’s jury of inquest on the day following returned this verdict:

John Jenkins, alias Simpkins, came to his death by being suspended by the neck with a rope attached to the end of the adobe building on the Plaza at the hands of an association of citizens styling themselves a Committee of Vigilance, of whom the following members are implicated. Then followed the names of the citizens who had been most conspicuous on the occasion.

When this verdict and the names were published on the day following, the Vigilance Committee ordered the names of all its members published likewise. The committee, however, was strongly opposed by the civil authorities and the legal fraternity generally, and Judge Campbell of the Court of Sessions, holding his court sessions on the days appointed, charged his Grand Jury that all those concerned in the illegal execution had been guilty of murder.

The Governor of the State, MacDougal, afterward United States Senator, issued a proclamation addressed to the people at large, in which he referred to the action of the people as the “despotic control of a self-constituted association unknown to and acting in defiance of the laws in the place of the regularly organized government of the country.”

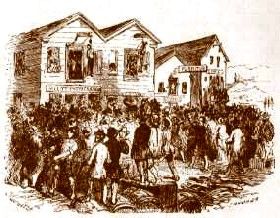

In August, the committee tried two men named Samuel Whittaker and Robert McKenzie. They were proven guilty of very serious offenses of burglary, robbery, and arson. It was understood that they were to be executed on the 21st of that month. A writ was issued by Judge Norton of the Supreme Court, commanding the sheriff to bring the prisoners before his court at a particular hour to be dealt with according to law. That night the sheriff and one deputy gained admission in some way to the rooms of the committee, where the prisoners were confined, led them downstairs, and placed them in charge of police officers awaiting them below. The committee took no immediate steps to remedy this interference with their purposes, but on the following Sunday, shortly after two o’clock in the afternoon a carriage turned into Broadway from DuPont Street and halted a short distance from the jail. At this hour, the prisoners were brought from their cells to hear divine service from the chaplain of the prison.

Criminals were hanged by the Vigilante Committee.

A pre-concerted rush was made from the outside; the prisoners were captured and carried off to the committee’s rooms. The fire bell tolled the signal for the assembly of the committee members, and along with them poured a stream of 15,000 people before their rooms, wild with excitement and yelling their approbation of the recapture of the prisoners. Brought face to face with the civil authorities, they would stand or fall by that act. The prisoners were sentenced to immediate execution and hanged at once from the windows of the committee’s rooms, in the presence of and with the approbation of the assembled multitude. Only seventeen minutes elapsed between the reception of the prisoners and their execution by order of the committee. Public opinion and the press declared that the Vigilance Committee had redeemed its honor.

Having thus established their authority and vindicated their cause, they arose to the full height of their power and struck terror among criminals of every degree. Henceforth there was no need for their services. Crime fled before their power of suppression, and they now left the execution of the laws in the hands of the civil authorities, retaining, however, their unaltered organization and imparting to the officer as well as the criminal within his hands the knowledge that at any moment when necessary the committee would again ring the alarm upon its fire-bell, and protect and preserve that social order which by their vigilant acts they had rescued from a chaos of crime and placed in the hands of the civil authorities.

As far as known, one woman died at the hands of the Vigilantes of California. She was a Spanish woman of remarkable beauty who dealt the game of Monte in the early days of Downieville. Clothed in her gay attire, her dark lustrous eyes flashing with the excitement of the game, and a profusion of dark locks falling upon her shoulders, together with a voluptuous form and superb carriage, she was the object of much attention from the rough miners and others who gathered around the table, and sat beneath her spell at the fascinating game of Monte.

Among the miners was a young man who had come from Kentucky to the distant El Dorado to seek his fortune among its gold hills. He was of fine physical appearance, genial disposition, warm and generous nature, and ever ready to do a good turn for his neighbor, or perform some deed of charity or kindness to the suffering, and withal as hard a toiler as the rest. He became a general favorite among all the rough miners.

Downieville California 1865

Of course, the sole places of amusement in those early days of Downieville were within the garish lights of the saloon and by the side of the Monte tables, over one of which the Spanish beauty presided. Like all his sex, the Kentuckian was charmed by her fascination. One night, with some companions, on his way to his tent after the game had closed and the senorita Dolores had retired, he passed the tent of the fair Spaniard and while peeping for an instant through the canvas lapel of her abode was suddenly, in a playful freak, pushed by his companions through the door into the darkness of her tent, and fell prostrate upon its floor. Without a moment’s hesitation or an inquiry as to the intruder’s identity, she sprang upon him like a tigress in its lair and plunged her dagger repeatedly in his prostrate form until he laid a bleeding corpse at her feet.

Information of the bloody deed soon reached every miner in the camp, and one and all hurried to the spot where the victim of her mad fury lay. The sight of his fair young face and sunny hair clotted with his lifeblood and the innumerable ghastly wounds upon his body as it lay uncovered in the hands of the doctor, who hoped to find some spark of life remaining, so worked upon the sympathies of the miners that some cheeks long unused to tears were wet from weeping. The young life had gone out forever, and the bright sunny eyes of the boy favorite of the camp were closed in the un-awakening slumber of death.

The rage of his rough friends knew no bounds. The woman was instantly seized and placed in the custody of guards while the Vigilance Committee of Downieville should determine her fate. That decree was death by hanging, and the murderess, with her hand yet reeking with her victim’s blood, was taken to the upper bridge of the Yuba and there hanged until life was extinct. Such was the swift punishment meted out by the rude populace in the excitement of the hour.

Vigilantes

It was, indeed, an ungloved iron hand that, in the homes of these early pioneers, first upheld the pillars of society and put to death the disturbers of the public peace in the absence of an organized form of government. They reasoned, however, that the institution of government for a people is that the governed may obtain security of life and property; that without such safeguard social order could not exist; society would be anarchy, and the law of right would be that of might.

The ignominious death of these outlaws at the hands of Vigilance Committees resulted from crimes, for the most part, cowardly and barbaric. Yet within the veins of some given over to deeds of violence that blacken the pages of criminal history flowed blood from which heroes are made. In moments of extreme peril, when humanity, overwhelmed by surrounding dangers, halted and surrendered. In despair, lay down to die, a lawless but master spirit from life’s royal blood rose like a giant to lead the way to hope and success.

When the news reached California that gold had been found in great abundance in the watershed of the Columbia River, without waiting for a confirmation of the rumor, great numbers of miners poured over the mountain walls of California and Nevada in search of their fortunes in the new goldfield. However, it was another of those stampedes that wreck the hopes and lives of the adventurous arid roving miner, and one by one, they struggled back to the more prosperous fields they had abandoned for this ignis fatuus [foolish affair.] One of these parties, nearly starved, attempted to reach Shoshone Falls through the thickly timbered mountains from Elk City. While searching for game one day, they chanced to strike a little stream that ran down from the mountain on the edge of a prairie lying near the center of a large snow-covered horseshoe opening to the south, about thirty miles in diameter. A fallen tamarack had thrown up the earth, and, moved by the instincts of his nature, one of the gold hunters took up a pan of the earth and carelessly washed it in the stream. What was his astonishment to reap as his reward a handful of rough little specimens of gold dust of the size of wheat grains! It was of poor quality, but it proved to be the original discovery of the great gold belt embracing Salmon, Warren, Boise, Owyhee, and Blackfeet, which afterward formed the political division of Idaho Territory, now in its Statehood.

On the third day of December 1862, a fierce storm swept over the whole gold belt, and the thousands of homeless and unprotected miners, who had been sleeping on the ground in their blankets while working their claims, began to pour over the horseshoe in the direction of Lewiston, taking with them the proceeds of their labor on the bar and in the gulch. A party of nine, of whom Joaquin Miller was one, were making their way through Walla Walla via Lewiston with a large amount of gold dust belonging to the individual members of the party. They had been followed from the mines by Dave English and Nelson Scott, two of the most noted desperadoes, accompanied by four others of like character but not so well known. There was no shadow of civil law to protect the honest toiler, nor any other form of protection as yet; at these mines, these men, black with crime, moved about the various tents with the same freedom as men of good character.

English was a thick-set, powerful man with a black beard and commanding manners. One of his gray eyes appeared to be askew. Otherwise, he was a fine-looking man, usually good-natured but terrible when aroused. Scott was tall, slim, brown-haired, with features as fair and delicate as a woman’s.

All of the band of six were young men well known in California, one of them having been connected with a circus. After six days of travel, the party of miners reached Lewiston in safety, and English and his companions arrived the following day. The river was frozen over, the steamboats tied up for the winter, and the ferry almost impassable.

The miners and robbers watched each other’s motions, and the latter knew that their motives had been divined. The miners had scarcely crossed the ferry when the robbers followed. The miners’ large amount of gold dust was the object of their pursuit. They were splendidly mounted and well-armed and prepared for any deed to accomplish their end. It was twenty-four miles to Petalia, the nearest station. The days were short, and the snow was deep. With the best of fortune, the miners did not expect to make it until night. At noon they left the Alpowa, and rode to a vast plateau without stone, stake, or sign to point the way to Petalia, twelve miles away.

Gold panning in the American West

The snow became deeper and more difficult, and a furious wind blinded and discouraged their horses. The cold was intense. They had not been an hour on this high plain before each man’s face was a mass of ice and their horses white with frost. The sun faded in the storm like a star of morning drowned in a flood of dawn. Grave fears now beset them. English and his robber party were now in advance.

Once they stopped, consulted, looked back, and moved on in a little while. The storm was so terrific that the trail behind them was obliterated the instant they passed on; the return was therefore impossible, had it been possible for them to re-cross the river should they reach it. Again the robbers halted, huddled together, looked back, and again struggled on, English, the man of iron, for the most part keeping the lead. The miners now knew they were in deadly peril, not from the robbers but from the storm. Again the robber band halted, grouped together, gesticulating wildly, as if in a violent argumentative altercation, and again moved slowly on. The party of Miners followed, the horses floundering in the deep snow, while the trail closed like a grave behind them. English shouted to them to approach about three o’clock in the afternoon, standing up to his waist in snow. Pushing on through the storm, with their heads bowed and necks bent, like cattle, shielding themselves in the fierce blast, they reached the robber party.

I tell you “h—l’s to pay, boys,” said English. “If we don’t keep our heads level, well go up the flume like a spring salmon. Which way do you think is the station?”

Snow Storm

No one could tell. To add to the dismay, they found that three of their party were missing. They shouted through the storm, but no answer came back. They never saw them again. In the spring, some Indians found and brought in a notebook, in which was recorded this writing: Lost in the snow December 19th, 1862, James A. Keep of Macoupin County, Illinois; Wesley Dean of St. Louis; Ed Parker of Boston. At the same time, they brought in a pair of boots containing bones of human feet. A party of citizens went out and found the remains of the three men, together with a large amount of gold dust.

English stopped, studied a moment, and then, resolving to take all into his own hands, said: “We must stick together; stick together and follow me. I will shoot the first man who refuses to obey and send him to hell “a-fluking.”

Again the robber chief, now in supreme command in the hour of danger and death, led on. The band struggled in silence, numb, helpless, and half dead. Scott seemed like a child beside his chieftain. The remainder of both parties were as feeble and as spiritless as he. English was the only one whose spirit rose above the storm. His whole ferocious nature seemed aroused. At times he swore like a madman. The storm increased in fury, darkness came suddenly on, and they could not see each other’s faces.

English shouted aloud, above the blast, Come up to me. They obeyed and huddled around him like children. There is but one chance, said he; cut your saddles off your horses. He got the horses as close together as possible and shot them down, throwing away his pistols as he emptied them. Placing the saddles on top of the pile of horses, he made each man wrap his blankets around him and huddle together on the mass. “No nodding now,” said English. “I’ll shoot the first man that fails to answer when I call him.”

To sleep a moment meant death by freezing, and this robber chief, this king of men, in the hour of dire peril and death, knew it. Every man seemed to surrender all hope, save this fierce man of iron. He moved as if in his element. He made a track in the snow around the party on the heap and kept constantly moving and shouting. Within an hour, they saw the effect of his rude action. The animal heat from the horses warmed their benumbed and stiffened limbs as they rose from their prostrate bodies while darkness and the storm reigned over them. Thus they remained during the stormy hours of the night. English, shouting and swearing through and above the blasts, tramped in the circular track he made about them, pistol in hand, to them awake and alive, while he battered his own body to keep it from freezing. Thus, the terrible night wore on until morning when English suddenly stopped shouting and uttered a terrible oath of surprise. The storm had suddenly lifted like a curtain, and far above in the heavens moved the round moon on its stately course. It was to that band of half-dead and well nigh frozen men as a pillar of flame to the children of Israel. They were saved. With the dawn of the morning, the iron man bade the others follow him. It was almost impossible for them to rise. They fell, rose again, fell, and finally stood on their feet, all save one, a small German named Ross. He was frozen to death.

At eleven o’clock in the morning, English, who still resolutely led the way, gave a shout of joy as he stood on the edge of a basaltic cliff and looked down on the parterre. A long straight pillar of white smoke rose from the station, like a column of marble supporting the overhanging dome. Again it was the pillar of cloud that led the children of Israel now leading these lost children of the mountains amid the snow wastes of the dreary plain. Warmed back to life again, they returned and brought in the body of their companion with his bag of gold dust, and in a few days, the trail was broken. The company of miners voluntarily gave to some of English’s band a portion of their wealth. English, however, resolutely refused to accept a present. They parted at the station, and the miners pursued their way in safety to Walla Walla, Washington.

Some months later, English, Scott, and another of his band, named Peoples, were arrested for highway robbery, and were placed, securely bound, under guard in a log house on the stage road. That night was organized the first Vigilance Committee in Idaho and, in fact, in the Northwest Territories. It consisted of six men belonging to the Idaho Express Company. At midnight they condemned the robbers to death and acquainted them of their fate. Scott asked for time to pray, English swore furiously, and Peoples was silent.

One of the vigilantes approached Scott while in the attitude of prayer and began to adjust the noose about his neck. English cried out, “Hang me first, and let him pray!”

The wonderful courage of the man appealed to the sympathies and admiration of these rough men of the mountains, and they would have spared him, but having proceeded thus far, they felt they could not falter now. They had but one rope and executed them one at a time. When the rope was adjusted about the neck of English, he was quietly asked by his executioners to invoke the mercy of his God. He held his head down a moment, muttered something, and then straightening up, turned toward Scott and said, “Nelson, pray for me a little, can’t you, while I hang?

People died without a motion or a struggle. When Scott’s turn came, he was still praying devoutly. He offered large sums of money, which he had secreted in the mountains, for his life, but they told him he must die too. Seeing there was no escape, he removed his watch and rings, kissed them tenderly, and handed them to one of the vigilantes, saying, “Send these to my poor Armina,” and quietly submitted to his fate. The three men lay dead and rigid upon the cabin floor at dawn. The blood that dried in the veins of one was of the kind that runs through a hero’s veins, and had he in his early days been guided in the nobler channels of life; he might have been a Ceasar or a Marlborough. With courage as sublime as that of the bride of Collatinus and the fortitude of an Alexander, he saved the lives of eleven human beings. Within four months after this sublime act of heroism died an ignominious death by the halter for robbing a stagecoach.

Bitterroot Mountains, Montana

Far to the northwest, among the canyons and gorges of the Rocky Mountains, and near the headwaters of the Missouri River, running up to the British line, and forming a part of the territorial boundary of the United States, is the young State of Montana. At the time which I am now writing, it was a young territory, or rather a part of Idaho Territory, with no settlements or signs of civilization save the mining camps scattered through its southern division. But its growth was rapid. Thriving, prosperous communities and cities of wealth and refinement have taken the places of rude mining camps. Traversed by railroads, it is now filled with farms and gardens, workshops and factories, mills and mines. It is inhabited by a brave, intelligent, self-reliant race, embracing all trades and professions of life. It now forms one of the brightest stars shining in the blue field of the imperial banner of the mighty sisterhood of States.

But, as I have stated, it was not always thus. It was once but the first low wash of the waves where now rolls a human sea mountain walls, rude civilization, tented homes, wild debauchery, robbery, rapine, and mid-day murders.

Early in the spring of 1862, the rumor of rich discoveries on the Salmon River flew through Salt Lake City, Colorado, and many other places in the far West. A wild rush to the new diggings resulted, and a stream of human beings set in for the new El Dorado by the toilsome way of Fort Hall and the Snake River. As their trains drew nearer the long-sought spot, they found further conveyance by wagons impossible, as the rocky, mountainous roads were impassable for wagons. They were likewise informed that the mines were already overrun by a vast army of gold hunters from California, Oregon, and all places on the Pacific slope. They also learned that many of those who had been driven by adverse circumstances from Salmon River had spread far over the adjacent country and that new discoveries had been made at Deer Lodge.

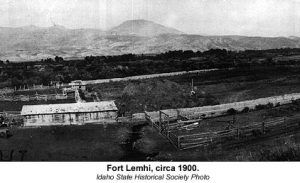

Fort Lemhi

The streams of immigration now diverged toward that point crossed the mountains between Fort Lemhi and Horse Prairie Creek and, taking a cut-off to the left, sought to strike the old trail from Salt Lake City to Deer Lodge and Bitter Root valleys. A mining camp was also established with success on Grasshopper Creek, afterward called Beaver Head Diggings. It was the first to work the gulches east of the Rocky Mountains. From these incipient labors flowed the great mining industries, which in an incredibly short space of time gave Montana her well deserved reputation as the richest gold-mining field discovered since that of California.

A tide of immigration now poured in from all directions, and with it came the bad as well as the good; and among the former were the desperadoes Henry Plummer, Charles Reeves, Moore, and Skinner, all of whom suffered death at the hands of the honest men of the Territory, who, when they found they could not apply the forms of law in a community where the written law was a dead letter or had never existed, maintained the right with their own strong hands to subdue the brute force of violence and murder. The wonderful discoveries at Alder Gulch of the almost fabulous placer diggings attracted a vast tide of rapid immigration known among gold seekers as a stampede. It likewise attracted many of the dangerous class, who saw a broad and rich field for their lawless operations.

They quickly organized themselves into a secret compact body, with signs, grips, and with a captain, lieutenants, secretary, road agents, and outriders, who became the terror of the whole country. A correspondence was inaugurated between Bannack and Virginia City, and surveillance was placed on all travel between those points. To such a fine point was their system carried that horses, men, and coaches were in some intelligible manner marked to designate them as objects of plunder. In this manner, the gang members were notified by their spies, often employed by the very object of their plunder, in time to prevent the escape of their victims. They were armed with a pair of revolvers, a double-barrelled shotgun with a large bore, the barrels cut short off, and a dagger or bowie knife. Thus armed, and mounted on swift and trained horses, and disguised with masks and blankets, they awaited their victims in ambush, from which, on the approach of a conveyance, they would spring forth, and covering the inmates with their guns, command them to alight and throw up their hands. If this order was not instantly obeyed, the result would be sudden death. Otherwise, they would be disarmed and made to throw their wealth upon the ground. Concluding their operations with a search for concealed property, they would permit the despoiled passengers to proceed on their way while they themselves rode rapidly in the opposite direction.

Wherever a new settlement was effected, or new discoveries of the precious metals were made, the bandits followed until their operations spread in all directions. They became the scourge of the mountains, and no men or class of men were safe from their attacks.

To illustrate the class of desperadoes engaged in this nefarious work, we will take the case of Henry Plummer, a man of such smooth manners and insinuating address that he was termed a perfect gentleman, although known to be both thief and assassin, and had once filled the office of marshal of Nevada City, whence, after having been twice imprisoned for murder, he had fled to Oregon, and thence to Montana. In Montana, he was elected sheriff of Beaver County. In company with his companion, Jack Cleveland, he first made his way to Bannack City, whose fame, in the winter of 1862 and 1863, had widely spread. It was the first mining camp of importance established east of the Rocky Mountains, and large immigration ensued, with the customary number of the ruffian class. Among them all, Plummer was chief, noted for his desperation and his skill in the rapid handling of his pistol. He shot and killed his friend and old acquaintance arid companion Jack Cleveland, who was disposed to dispute his title as chief and frequently boasted of his murderous exploits.

Shortly after that occurrence, another of the gang, named George Ives, was conversing on the street with his friend George Carhart and, not liking the style of his speech, laid him low with a shot from his revolver.

Another eminent road agent, named Haze Lyon, owed a citizen of Bannack four hundred dollars for board and lodging. One morning, having won a large sum of money the night previous at the gaming table, was asked by his landlord to settle his account. He answered the modest request by drawing his revolver and ordering the citizen to dust out, with which gentle command he immediately complied.

Henry Plummer

Plummer was tried for the murder of Cleveland and acquitted on the ground that his opponents’ language was irritating. Charles Reeves and a man named Williams, who had fired into a camp of friendly Indians just to see how many they could kill at one shot, were also tried and acquitted. Others who had likewise been guilty of heinous offenses were also acquitted. The baser elements of society felt secure in the performance of their lawless deeds, and murder and robbery went on unmolested.

Plummer, who had been chosen chief of the road agents, had likewise, as previously stated, succeeded in having himself elected sheriff of the county and appointed two of his band as deputies. In the meantime, an honest man had been elected sheriff at Virginia City and was informed by Plummer that he would live much longer if he would resign his office in his favor. Pear of assassination compelled him to do as bidden, and Plummer became sheriff at both places. With his robber deputies to execute his orders, the people of Montana were at the mercy of thieves and bandits. One of his deputies was an honest man and, becoming too well versed in the doings of Plummer and associates, was sentenced to death by the road agents and publicly shot by three of the band. There was no longer any security of life on the arid property.

A Dutchman sold some mules and received the money in advance as driving the animals on a public road to deliver them to the purchaser when he was met by Ives, murdered, and robbed of both money and mules. The sight of this man’s body brought into town in a cart stirred the blood of the honest men of the community, and they determined to capture and hang his murderer. A party of citizens thoroughly armed scoured the country, surprised accomplices of the murderer, and wrung from them the confession that George Ives was the murderer. He was captured and taken a prisoner to Nevada City by the following evening. He was given a trial. The bench was a wagon; the jury, twenty-four honest men; the aroused citizens stood guard with guns in hand while the trial proceeded, with their eyes fixed upon the desperadoes, who had gathered in force to aid, support, and, if possible, to rescue their comrade in crime. Counsel was heard on both sides; reliable witnesses proved the prisoner guilty of numerous murders and robberies. Condemned to death, his captors repressed every rescue attempt and held the prisoner with cocked and leveled guns. It was a moonlight night, and the campfire shed its gleam. Amid the shouts and yells and murderous threats of the assembled ruffians, the condemned assassin and cowardly murderer was led to the gallows, upon which he expiated his various crimes. The next day the far-famed Vigilantes of Montana were organized. Five brave men in Nevada City and one in Virginia City, the towns lying adjacent, formed the secret league who opposed, on the side of law and order, force to force and dread to dread against the road agents’ organization. This league became as terrible to the outlaws as they had been to the honest, order-loving, and industrious part of the community.

Plummer, the sheriff, was seized, and before lie could escape, he was executed on a Sunday morning, together with two of his robber deputies, on a gallows he had erected.

To put an end to the long reign of terror, the vigilantes assumed the duties of captors, judges, jurors, and executioners. But they were not guilty of excesses. They struck terror to those who had defied the weaker arm of the law by sure, swift, and secret punishment of crime. In no case was a criminal executed without evidence establishing his guilt. In this respect, how closely they hewed to the line is attested by the dying remarks of one of the last men hanged by their order: “you have done right. Not an innocent man hanged yet!” But it was understood that the work they had undertaken to perform should be faithfully and thoroughly performed; that there should be no halfway measures, no reprieves, the verdict having once been rendered.

An instance of the severe labor, exposure and real hardship encountered by these guardians of peace and order is furnished in the pursuit and capture of William Hunter.

At the time of the execution of Boone Helm and his five confederates, Hunter managed to elude his pursuers by hiding by day among the rocks and brush, seeking food by night among the scattered settlements along the Gallatin River. Four of the vigilantes, determined and resolute men, volunteered to arrest him. They crossed the divide and forded the Madison River when huge cakes of floating ice swirled down on the horses’ flanks, threatening to carry them down. Their camping ground was the frozen earth, the weather intensely cold, and they slept at night under their blankets by the side of a fire they had built. Their way led through a tremendous snowstorm the next day, which they welcomed as an ally. About two o’clock in the afternoon, they reached Milk Ranch, twenty miles from their destination, obtained their supper, and proceeded, after dark, with a guide well acquainted with the country. At midnight they reached the cabin where they learned Hunter had been driven to seek refuge from the severe storm and cold. They halted, unsaddled, and rapped loudly at the door. On being admitted, they found two persons in the cabin – two visible and one covered up in bed.

The vigilantes made themselves as comfortable as possible before a blazing fire on the hearth. They talked of mining, prospecting, panning-out, and terms of that character as if they were traveling miners. Before going to sleep, however, they carefully examined the premises as to its exits and placed themselves in such a manner as to command the only entrance and exit. They refrained from saying anything concerning their real business until early the following morning when their horses were saddled, and they appeared ready to proceed on their journey. Then they asked who the sleeper was, who had never spoken or uncovered his head. The reply was that he was unknown; he had been there two days, driven in by the storm. Asked to describe him, the description was that of Hunter.

The vigilantes then went to the bed, and allying a firm hand on the sleeper, he gripped the revolvers in his hand beneath the bedclothes. “Bill Hunter” was called upon to arise and behold grim men with guns leveled at his head. He asked to be taken to Virginia City, but he soon found a shorter road. Two miles from the cabin, they halted beneath a tree with a branch over which a rope could be thrown and a spur to which the end could be fastened. Scraping away a foot of snow, they built a fire and cooked their breakfast. After breakfast, they consulted and took a vote as to the disposition of the prisoner. That vote determined upon instant execution. The perils of the long tramp over the mountain divide, the crossing of the icy stream, the small force involved in his capture, and the certainty of an attempt at rescue when his capture became known to his accomplices all rendered this necessary. The lengthy catalog of crimes he had committed was read to him, and he was asked to plead any extenuating circumstances in his own behalf. There were none, and he remained silent. He had once been an honest, hard-working man and was believed to be an upright citizen. In an evil hour, he joined his fortunes with the wicked band that had likewise perished on the scaffold. His only request was that his friend in the States should not be informed of the manner of his death.

Thus died the last of Plummer’s famous band of outlaws, executing in his last moments the pantomime of grasping an imaginary pistol, cocking it, and discharging in rapid succession its six ghostly barrels.

John W. Clampitt, 1891. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2022.

Bannock, Montana Gallows

About the Author: John W. Clampitt wrote this article for Harper’s Monthly Magazine, Volume 83, Issue 495, August 1891. However, as it appears here, the story is not verbatim as it has been edited for clerical errors and updated for the modern reader. It has also been pointed out to Legends Of America by a reader that Clampitt’s story is lifted (some outright plagiarized) from “The First Vigilance Committees”, by Gustav Bergenroth, published in Charles Dickens’ Household Words, in November of 1856.

Also See:

Adventures in the American West