Wild Bill – 1867 Harper’s Weekly Article – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By George Ward Nichols, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867

This article, written by George Ward Nichols, was excerpted, in part, from an article that appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, entitled Wild Bill, in February 1867, now in the public domain. The article is not verbatim, as glaring errors, such as Nichols referring to Bill Hickok as William Hitchcock, and other grammatical and spelling corrections have been made. In addition, it was widely criticized as exaggerating Bill Hickok’s deeds, defaming the people of Springfield, Missouri, and included numerous downright inaccuracies. You can read about the criticisms after this article.

~~

Wild Bill Hickok

Several months after the ending of the Civil War I visited the city of Springfield in southwest Missouri. Springfield is not a burgh of extensive dimensions, yet it is the largest in that part of the State, and all roads lend to it — which is one reason why it was the point of support, as well as the base of operations for all military movements during the war.

On a warm summer day, I sat watching from the shadow of a broad awning the coming and goings of the strange, half-civilized people who, from all the country round, make this a place for barter and trade. Men and women dressed in queer costumes; men with coats and trousers made of skin, but so thickly covered with dirt and grease as to have defied the identity of the animal when walking in the flesh. Others wore homespun gear, which oftentimes appeared to have seen lengthy service. Many of those people were mounted on horse-hack or mule-back, while others urged forward the unwilling cattle attached to creaking, heavily-laden wagons, their drivers snapping their long whips with a report like that of a pistol-shot.

In front of the shops which lined both sides of the main business street, and about the public square, were groups of men lolling against posts, lying upon the wooden sidewalks, or sitting in chairs. These men were temporary or permanent denizens of the city, and were lazily occupied in doing nothing. The most marked characteristic of the inhabitants seemed to be an indisposition to move, and their highest ambition to let their hair and beards grow.

Here and there, upon the street, the appearance of the army blue betokened the presence of a returned Union soldier, and the jaunty, confident air with which they carried themselves was all the more striking in its contrast with the indolence which appeared to belong to the place. The only indication of action was the inevitable revolver which everybody, excepting, perhaps, the women, wore about their persons. When people moved in this lazy city they did so slowly and without method. No one seemed in baste. A huge hog wallowed in luxurious ease in a nice bed of mud on the other side of the way, giving vent to gentle grunts of satisfaction. On the platform at my feet lay a large wolf-dog literally asleep with one eye open. He, too, seemed contented to let the world wag idly on.

The loose, lazy spirit of the occasion finally took possession of me, and I sat and gazed and smoked, and it is possible that I might have fallen into a Rip Van Winkle sleep to have been aroused ten years hence by the cry, “Passengers for the flying machine to New York, all aboard!” when I and the drowsing city were roused into life by the clatter and crash of the hoofs of a horse which dashed furiously across the square and down the street. The rider sat perfectly erect, yet following with grace of motion, seen only in the horsemen of the plains, the rise and fall of the galloping steed. There was only a moment to observe this, for they halted suddenly, while the rider springing to the ground approached the party which the noise had gathered near me.

“This yere is Wild Bill, Colonel,” said Captain Honesty, an army officer, addressing me.

He continued:

“How are yer, Bill? This yere is Colonel N____, who wants ter know yer.”

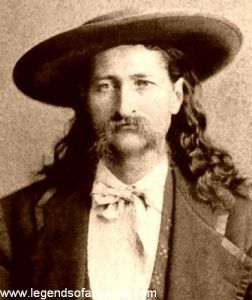

Let me at once describe the personal appearance of the famous Scout of the Plains, William Hickok, called “Wild Bill,” who now advanced toward me, fixing his clear gray eyes on mine in a quick, interrogative way, as if to take my measure.

The result seemed favorable, for he held forth a small, muscular hand in a frank, open manner. As I looked at him I thought his the most handsome physique I had ever seen. In its exquisite manly proportions, it recalled the antique. It was a figure Ward would delight to model as a companion to his Indian.

Springfield, Missouri in the 1870s

Bill stood six feet and an inch in his bright yellow moccasins. A deer-skin shirt, or frock it might be called, hung jauntily over his shoulders and revealed a chest whose breadth and depth was remarkable. These lungs had had growth in some twenty years of the free air of the Rocky Mountains. His small, round waist was girthed by a belt that held two of Colt’s Navy revolvers.

His legs sloped gradually from the compact thigh to the feet, which were small, and turned inward as he walked. There was a singular grace and dignity of carriage about that figure which would have called your attention meet it where you would. The head which crowned it was now covered by a large sombrero, underneath which there shone out a quiet, manly face; so gentle is its expression as he greets you as utterly to belie the history of its owner, yet it is not a face to be trifled with.

The lips thin and sensitive, the jaw not too square, the cheekbones slightly prominent, a mass of fine dark hair falls below the neck to the shoulders. The eyes, now that you are in friendly intercourse, are as gentle as a woman’s.

In truth, the woman nature seems prominent throughout, and you would not believe that you were looking into eyes that have pointed the way to death to hundreds of men. Yes, Wild Bill with his own hands has killed hundreds of men. Of that, I have not a doubt. He shoots to kill, as they say on the border.

In vain did I examine the scout’s face for some evidence of murderous propensity. It was a gentle face, and singular only in the sharp angle of the eye, and without any physical reason for the opinion, I have thought his wonderful accuracy of aim was indicated by this peculiarity. He told me, however, to use his own words:

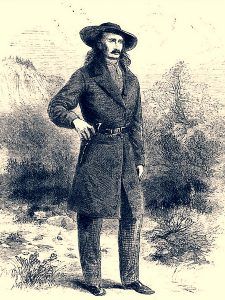

Wild Bill Hickok illustration from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February, 1867.

“I allers shot well; but I come ter be perfeck in the mountains by shootin at a dime for a mark, at bets of half a dollar a shot. And then until the war I never drank liquor nor smoked,” he continued, with a melancholy expression; “war is demoralizing, it is.”

Captain Honesty was right. I was very curious to see “Wild Bill, the Scout,” who, a few days before my arrival in Springfield, in a duel at noonday in the public square, at fifty paces, had sent one of Colt’s pistol-balls through the heart of a returned Confederate soldier.

Whenever I had met an officer or soldier who had served in the Southwest I heard of Wild Bill and his exploits until these stories became so frequent and of such an extraordinary character as quite to outstrip personal knowledge of adventure by camp and field, and the hero of these strange tales took shape in my mind as did Jack the Giant Killer or Sinbad the Sailor in childhoods days. As then, I now had the most implicit faith in the existence of the individual; but how one man could accomplish such prodigies of strength and feats of daring was a continued wonder.

In order to give the reader a clearer understanding of the condition of this neighborhood, which could have permitted the duel mentioned above, and whose history will be given hereafter in detail, I will describe the situation at the time of which I am writing, which was late in the summer of 1865, premising that this section of country would not today be selected as a model example of modern civilization.

At that time peace and comparative quiet had succeeded the perils and tumult of war in all the more Southern States. The people of Georgia and the Carolinas were glad to enforce order in their midst, and it would have been safe for a Union officer to have ridden unattended through the land.

In Southwest Missouri, there were old scores to be settled up. During the three days occupied by General Smith, who commanded the Department and was on a tour of inspection in crossing the country between Rolla and Springfield, a distance of 120 miles, five men were killed or wounded on the public road. Two were murdered a short distance from Rolla — by whom we could not ascertain. Another was instantly killed and two were wounded at a meeting of a band of Regulators, who were in the service of the State, but were paid by the United States Government. It should be said here that their method of “regulation” was slightly informal, their war-cry was, “A swift bullet and a short rope for returned rebels!”

I was informed by General Smith that during the six months preceding not less than 4,000 returned Confederates had been summarily disposed of by shooting or hanging. This statement seems incredible, but there is the record, and I have no doubt of its truth. History shows few parallels to this relentless destruction of human life in a time of peace. It can’t be explained only upon the ground that, before the war, this region was inhabited by lawless people. At the outset of the rebellion, the merest suspicion of loyalty to the Union cost the patriot his life; and thus large numbers fled the land, giving up home and every material interest. As soon as the Federal armies occupied the country these refugees returned.

Once securely fixed in their old homes they resolved that their former persecutors should not live in their midst. Revenge for the past and security for the future knotted many a nerve and sped many a deadly bullet.

Wild Bill did not belong to the Regulators. Indeed, he was one of the law and order party. He said:

“When the war closed I buried the hatchet, and I won’t fight now unless I’m put upon.”

Bill was born to Northern parents in the State of Illinois. He ran away from home when a boy, and wandered out upon the plains and into the mountains. For fifteen years he lived with the trappers, hunting, and fishing. When the war broke out he returned to the States and entered the Union service. No man probably was ever better fitted for scouting than he. Joined to his tremendous strength he was an unequaled horseman; he was a perfect marksman; he had a keen sight and a constitution that had no limit of endurance. He was cool to audacity, brave to rashness, always possessed of himself under the most critical circumstances; and, above all, was such a master in the knowledge of woodcraft that it might have been termed a science with him — a knowledge which, with the soldier, is priceless beyond description. Some of Bill’s adventures during the war will be related hereafter.

The main features of the story of the duel were told me by Captain Honesty, who was unprejudiced if it is possible to find an unbiased mind in a town of 3,000 people after a fight has taken place. I will give the story in his words:

“They say Bill’s wild. Now he isn’t any sich thing. I’ve known him goin on ter ten year, and he’s as civil a disposed person as you’ll find he-e-arabouts. But he won’t be put upon.”

“I’ll tell yer how it happened. But come inter the office; thar’s a good many round hy’ar as sides with Dave Tutt— the man that’s shot. But I tell yer ’twas a ‘far fight. Take some whisky? No! Well, I will, if yer’l excuse me.”

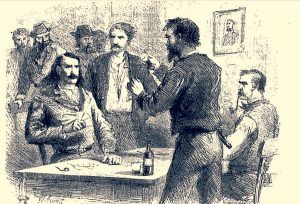

Bill Hickok and Tutt illustration from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867.

“You see,” continued the Captain, setting the empty glass on the table in an emphatic way, “Bill was up in his room a-playin seven-up, or four-hand, or some of them pesky games. Bill refused ter play with Tutt, who was a professional gambler. Yer see, Bill was a scout on our side durin the war, and Tutt was a reb scout. Bill had killed Dave Tutt’s mate, and, atween one thing and another, there war an unusual hard feelin atwixt ‘em.”

“Ever since Dave come back he had tried to pick a row with Bill; so Bill wouldn’t play cards with him anymore. But Dave stood over the man who was gambling with Bill and lent the feller money. Bill won bout two hundred dollars, which made Tutt spiteful mad. Bime-by, he says to Bill:

‘Bill you’ve got plenty of money — pay me that forty dollars yer owe me in that horse trade.’

“And Bill paid him.” Then he said:

‘Yer owe me thirty-five dollars more; yer lost it playing with me t’other night.’