William E. Mathewson – The Other Buffalo Bill – Legends of America (original) (raw)

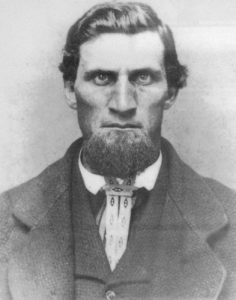

William “Buffalo Bill” Mathewson

Though not as well known in history as the more famous “Buffalo Bill” Cody, the first man to hold the moniker of Buffalo Bill was William E. Mathewson, a daring explorer, hunter, Indian scout, and fighter who did much to prepare the pathway for western expansion.

Born on January 1, 1830, in Triangle, New York, William was the son of Joseph and Eliza Stickney Mathewson, the seventh in a family of eight children. The family lived and worked on a farm, but from a young age, William was more inclined towards a hunter’s wild and roving life, and he longed for the adventurous life of a frontiersman. After his father’s death, he remained with his mother until he was ten years old, attending country schools, and then resided with an older brother for three years. At 13, he went into the lumber regions of Steuben County, New York, and there and in western Pennsylvania, he was employed in the lumber and mill business until he was 18.

During this time, he would set out with other hunters on long hunting expeditions in the fall of each year, going to Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Canada and returning home in the spring. A part of the time, he was engaged in looking up pinelands in Wisconsin and Minnesota and, at one time, acted as a guide to a party of land buyers through the unknown West. In 1849 he embraced an opportunity offered him by the North West Fur Company, with headquarters at Fort Benton, Montana. While employed, he traveled with other trappers through Nebraska, the Dakotas, and Wyoming, trading with the Indians when they were friendly and fighting them when they were hostile. At one time, the party was surrounded by a band of Blackfeet Indians and did not dare to leave the stockade to give battle, but after severe fighting, the Indians were driven off.

Kit Carson

After remaining nearly two years in the employ of the North West Company, Mathewson joined a party of hunters led by Kit Carson in 1852. Within this party were several famous men of the time, including Lucien Maxwell, James and John Baker, Charles and John Autobee, and others. This party traveled south to the head of the Arkansas River in Colorado, traversing the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, crossing the headwaters of the Little Big Horn — where General George Armstrong Custer was later killed — and the north and south forks of the Platte River, and passed down through the country to present-day Denver, Colorado.

Later in 1852, he entered the employ of the Fort St.Vrain Trading Post at the foot of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. He traded with the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache Indians. In the fall of 1856, he partnered with Horace Green, employing more trappers to work along the headwaters of the Arkansas and Republican Rivers. In the spring of 1857, they traveled to Independence, Missouri, where they disposed of their pelts.

Having traveled over the entire unsettled region between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains, Mathewson could readily see that immigration would soon burst through the Missouri River boundary. The settlement of Kansas and regions farther west would be rapid. He soon determined to establish a trading post along the Santa Fe Trail in Kansas, although no man had as yet dared to attempt such a thing so far away from military protection.

In the summer of 1858, in partnership with Asa Beach, he established a trading post on Cow Creek, which they made headquarters until 1861. He then traveled among the different tribes on trading expeditions. Mathewson earned the nickname “Buffalo Bill” when he saved numerous settlers from starvation during the winter of 1860-1861. The drought of 1860 had ruined the crops the settlers had planted, leaving them without a reserve food source for the winter. Mathewson responded by supplying them with buffalo meat, for which he refused payment. He was said to have killed as many as 80 buffalo in a single day for the settlers. He also accommodated the overland mail route from Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Kiowa Chief Satanta.

In 1861 he had a personal encounter with Kiowa Chief Satanta, the boldest and most powerful Kiowa Indian chief. With a small band of warriors, Satanta entered the post and announced his intention to take Mathewson’s life in revenge for one of his braves’ deaths while attempting to steal a horse from the post. It took but an instant for Mathewson to floor the Kiowa chief and give him a severe beating, and the followers of Satanta, driven from the house at the point of a revolver, were forced to carry their defeated leader back to camp. Satanta swore revenge for this humiliating defeat, and Mathewson, hearing of this, and deeming it best to settle the matter once and for all, rode out alone on the prairie in search of his enemy. Learning of the pursuit, Satanta fled and did not return for more than a year. When he returned, he acknowledged Mathewson as his master and entered into a treaty with him, giving a number of his best Indian horses as a token of his subservience. Mathewson was henceforth known in every Indian camp of the plains as “Sinpah Zilbah,” meaning “long-bearded dangerous white man.”

In the summer of 1864, when the Indians took the warpath and were terrorizing Kansas settlers, Satanta warned Mathewson of an uprising three weeks in advance and entreated him to leave, saying that in revenge for having been fired on by a regiment of soldiers, the Indians were not going to leave a white man, woman, or child alive west of the Missouri River. Instead of fleeing, however, Mathewson sent all of the settlers to places of safety and then hunkered down with a few brave men to hold his trading post. He and his men, five in number, were armed with the first breech-loading rifles that had ever been used on the plains of Kansas. On the morning of July 20th, 1,500 Indians surrounded the Mathewson post and, for three days, attacked and reconnoitered. Still, they were repeatedly forced to retreat upon coming within range of the deadly fire of the breech-loading rifles. The Indians lost about 160 horses and a score or more of their kinsmen before they finally retreated.

Indian Attack by Charles Marion Russell

When first warned of the Indian uprising, among the first things Mathewson did was to write to the Overland Transportation Company and Bryant, Banard & Company, telling them not to send any wagons out. In reply, he received from the latter word that they had already started a train loaded with modern rifles, and the letter ended with the appeal, “For God’s sake, save this train, as it is loaded with arms and ammunition.” On the fourth day of the siege, this overland train of 147 wagons, loaded with supplies from the government posts of New Mexico and in charge of 155 men, appeared upon the scene. Ignorant of the Indian uprising, the train had come within three miles of the post, and upon the morning of the fourth day of the battle, Mathewson discovered that the Indians had departed during the night. He mounted the highest building of the post and, to the eastward, three miles away, saw through his field glass the government train, drawn up in the usual camp half-circle and surrounded by Indians. After studying the situation, he asked his most trusted man if the stockade could be held in his absence. He was assured it could, so he rode out with his Sharp’s rifle and six Colt revolvers. When he reached the wagon camp, he burst into its midst with guns blazing. He quickly mounted one of the wagons, split open the boxes, and handed out rifles and ammunition to the men. In a moment, the well-directed fire was turned on the astonished and bewildered Indians, who, after continuing the fight for a short time, in which many of them were killed or wounded, beat a hasty retreat. To complete the victory, Mathewson organized and mounted the teamsters and gave chase, driving the Indians miles away. Then, after burying the dead and repairing the ravages of the fight, the train moved on to its destination.

Elizabeth Mathewson

In August 1864, William married an English girl who had immigrated to the United States with her parents. She became an expert in using the rifle and revolver and became her husband’s companion among the Indians. The couple would eventually have two children.

Later, in 1864, Mathewson joined General James G. Blunt’s expedition as a scout, with whom he remained until the close of the Civil War. The government began sending troops out to subdue the Indians when the war was over. Still, later orders came to the commander of the Western Department to get someone to go to the Indians and try to get them to come into peace negotiations. Mathewson was finally decided upon and duly commissioned for the purpose. He started from Larned, Kansas, going to the mouth of the Little Arkansas River and, on the fourth day of his journey, saw the Indian camp. He was successful in his mission, and the desired council was held between the government’s commissioners and the Indians.

In May 1866, he was presented with a beautiful pair of six-shooters with carved ivory handles, silver-mounted and inlaid with gold, by the Overland Transportation Company to recognize his saving 155 men and 147 wagons of government supplies.

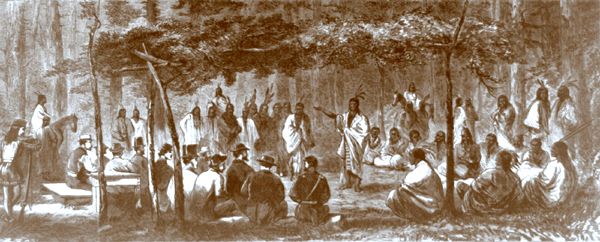

In 1867 Indians again took to the warpath, and Mathewson acted as mediator. He went to Junction City and telegraphed Washington, asking General Hancock’s recall and saying he would take care of the Indians. His request was complied with. He got the Indians together for another treaty, known as the Medicine Lodge Treaty, after which they ceded all their rights and title to lands in Kansas and Colorado to the government and went back to their reservations.

Medicine Lodge, Kansas Treaty Council

For several years, he traveled with different tribes with the Quaker commission and settled near Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where he remained until 1876. Having a thorough knowledge of their customs and manners and understanding their speech, he was the only man who could travel among the Indians unmolested, as they both feared and respected him. During the years that he lived among the natives, he settled internal quarrels and did all in his power to satisfy them. Between 1865 and 1873, he saved 54 women and children from death at the hands of the Indians. One of these was a young woman captured in Texas by Kiowa Indians and brought into Kansas, where she escaped. Learning of her escape and a reward for her recapture, Mathewson, determined to save the girl, trailed her and, finding her more dead than alive, took her to Council Grove. After recovering, she married and lived for several years. Mathewson also arranged with a Kiowa chief to release two little girls held captive by them and whose parents were killed by the Indians.

In 1868 Mathewson acquired a homestead near the Arkansas River, which would soon become the heart of the city of Wichita. He built a home and began a profitable career as a civic leader and banker there. His first wife died on October 1, 1885, and he married for a second time to Mrs. Tarleton of Louisville, Kentucky, in May 1886.

William Matthewson’s home in Wichita, Kansas.

Later in life, he had asthma, and when he died on March 22, 1916, he was buried at Highland Cemetery in Wichita. At that time, he was referred to as “the original Buffalo Bill.” Not long after that, his son, William Mathewson Jr., received a letter from the more famous scout-turned-showman, Buffalo Bill Cody. The letter voiced Cody’s condolences and acknowledged that fellow frontiersman William Mathewson was truly the first “Buffalo Bill.”

Although a man of great accomplishments, Mathewson’s lack of national fame was his own choice, he was a modest man who didn’t view his life as extraordinary; instead, he did what needed doing. Though he was approached by newspaper and magazine writers and dime-novel authors who wanted to tell the story of his life on the Western frontier, he always rejected the proposals.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

Also See:

Sources:

History.net

Kansapedia

_Portrait And Biographical Album of Sedgwick County, Kansa_s, Chapman Brothers, 1888

William Mathewson Obituary