No, Chinatown Did Not "Take Over" Little Italy - Lower East Side History Project (original) (raw)

I see numerous comments a day on social media posts claiming “Chinatown took over Little Italy.” These comments sadly show a deep misunderstanding of not only Italian-American history, but NYC history in general. (I’d like to think it is ignorance and not xenophobia.) Well, I would like to offer the following alternative narrative.

Article takeaways:

- Chinese settled in the district about the same time, if not a little earlier than Italian immigrants.

- The largest driving forces of a shrinking Italian population are gentrification and Americanization.

- Lower Manhattan’s Italian enclave was much larger than most people realize or remember.

How Big Was Little Italy?

Many people these days consider Little Italy to be Mulberry Street, between Grand and Canal Street. By those metrics, it certainly does look like Chinatown has engulfed the entire community. However, the bulk of Lower Manhattan’s traditional Italian enclave stretched roughly from City Hall/Brooklyn Bridge to Washington Square Park, south to north, and Bowery to 7th Avenue, east to west. In the 4th Ward, it extended east past Bowery, and in the “East Village,” there was a large Italian community between E.10 and E.14th Streets. In that context, you can see that Chinatown now occupies but a fraction of the traditional ethnic neighborhood:

The traditional Italian enclave roughly bordered by the black line, and today’s Chinatown is roughly bordered by the red line.

Early Chinese Settlement

During the 19th century, the United States saw an influx of immigrants from China — mainly Canton. The discovery of gold in 1840s California and the need for cheap labor for the Transcontinental Railroad led to a significant Chinese population in the West.

However, by the 1870s, economic downturns led to job scarcity and wage decline, resulting in increasing resentment among the European population towards the Chinese immigrants. This, coupled with violence and discrimination, led many Chinese immigrants to migrate east to larger cities like NYC, where there were more job opportunities.

The Birth of Chinatown

By the 1870s, Chinese immigrants began to concentrate around Mott Street, north of Worth Street in NYC. By 1880, Chinatown was home to about 1,000 Chinese immigrants. However, the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which restricted Chinese immigration, slowed its growth. A large majority of these immigrants were men, who had left their wives back home in China for economic opportunities. Some sources say the ratio was 10 men to every 1 woman, so the population remained low for many decades.

Despite the restriction on immigration, Chinatown continued to flourish, largely due to an economy based on tourism. However, it was not until the 1940s, with the lifting of the Chinese exclusion laws, and the 1960s, with the Immigration and Nationality Act, that Chinatown saw a significant surge in its population.

The Italian Immigration Wave

Little Italy began to take shape in the late 1800s as well, when waves of (largely Southern) Italian and Sicilian immigrants arrived in NYC. Like the Chinese, Italian immigrants were fleeing hardships at home. America, not exactly for altruistic reasons, opened its arms because it needed workers to build its burgeoning cities and work its plantations after slavery was abolished.

Between 1880 and 1924, over four million Italians arrived in America, with tens of thousands settling in NYC. By 1924, when the bridges, subways, and railroads were built and streets paved, America closed the door to most European immigrants.

Birth of Little Italy

Similar to the Chinese, the majority of early immigrants from Italy were males. The area around City Hall, known as “Five Points,” became home to the earliest of these laborers, as boarding houses began springing up to accommodate them. By the end of the 19th century, the Five Points was nearly all Italian. Through the years, the district grew and spread north, though the poorest remained in the southern portion of the neighborhood for many decades.

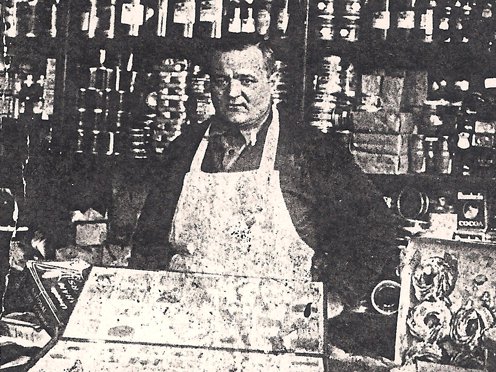

My great-grandfather, Ernesto “Cappy” Capitini in his early-century grocery store in Little Italy

The Shrinking Little Italy. Where Did All The Italians Go?

With the expansion of Chinatown starting in the 1970s to the south, and the increasing cost of living in the 1990s (gentrification) from the north, Little Italy began to contract. By 2010, the U.S. census showed not a single person born in Italy lived in Little Italy.

However, Italians actually started moving out of the area much earlier, after WWII. The economy was booming, and after decades of violent discrimination, Italians were starting to become more accepted among the Anglo-Americans (luckily they liked our food and entertainers), so many moved to the suburbs of Long Island, Staten Island, and New Jersey. (And eventually the “Sixth Borough,” Florida!)

As new immigrants, it is important to stick together and remain within proximity of each other for safety, language, and economic reasons. But after a few generations, historically, that cultural nucleus is less important. As decedents of immigrants become educated and Americanized, a lot of traditional culture becomes diluted.

By the time Chinese (and others) started arriving in large numbers, and before the rents in NYC started to skyrocket, Italians had been here for several generations and just followed the natural migration path as the Irish, German, Jewish, and other immigrants who moved out of the slums into greener pastures. (Can you name any remaining Irish neighborhoods?)

Those landlords who bought their buildings for tens of thousands of dollars back in the day were being offered millions. Many took the money and ran. Along with them went the century-old Italian market on the first floor, and all the remaining life-long residents who got priced out. And that is how every neighborhood in NYC fell like dominoes over the last 20 or so years.

Little Italy, rebranded

Today, Little Italy has been rebranded as NoLita (“North of Little Italy”), South Village, and yes, Chinatown. For better or worse, what is left are those three blocks along Mulberry Street, and a few leftover old-timers. It is still a wonderful place to visit, and one of the few places on earth you can eat a cannoli, then walk across the street to pick up an eggroll.

Eric is a 4th generation Lower East Sider, professional NYC history author, movie & TV consultant, and founder of Lower East Side History Project.