Planet Nine: Is the search for this elusive world nearly over? (original) (raw)

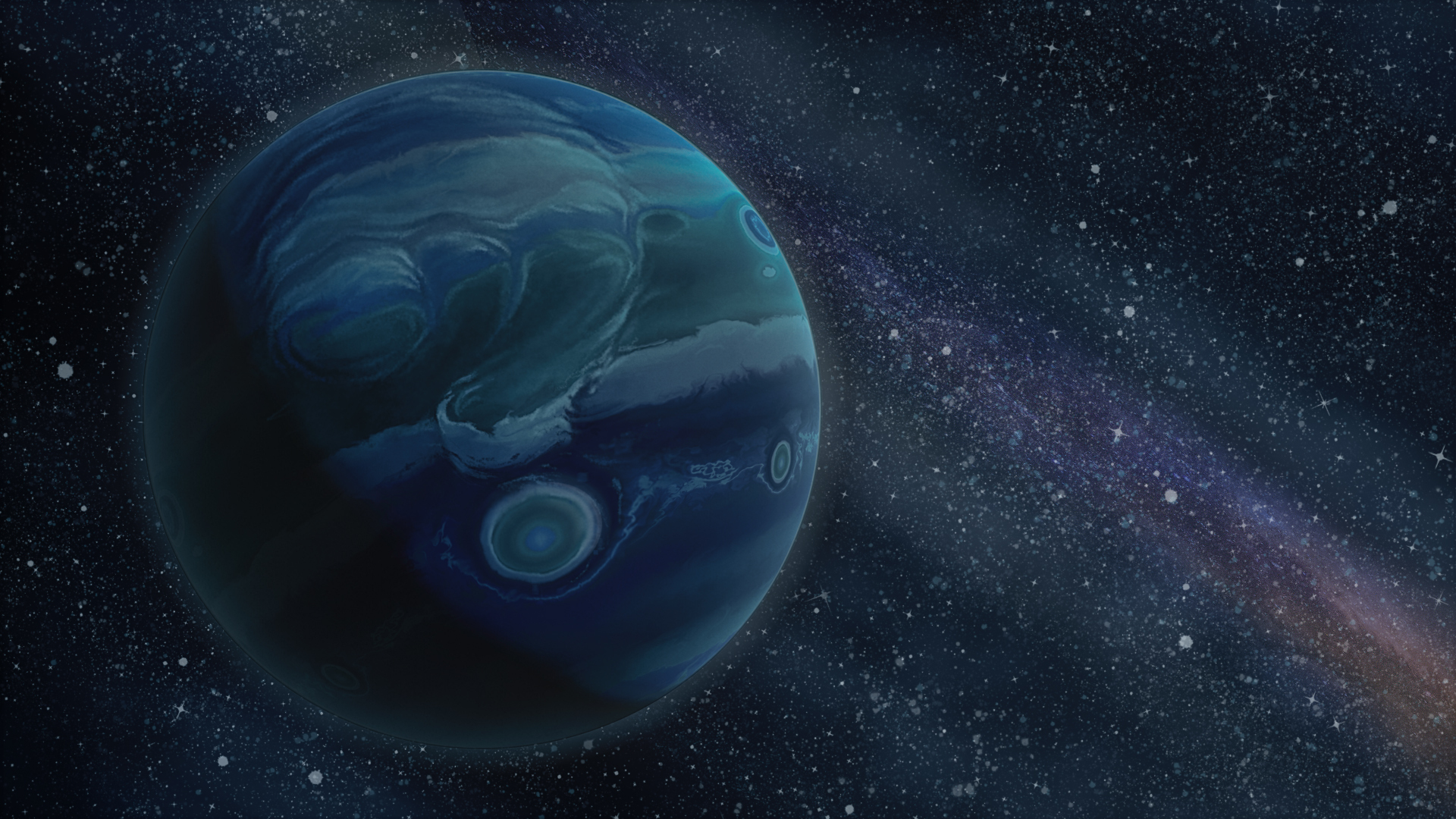

Scientists think there may be a ninth planet hiding in the distant reaches of the solar system — and a new telescope could finally prove its existence. (Image credit: Nicholas Forder for Live Science)

Deep in the outer reaches of the solar system — so far away from the known planets that the sun would barely be distinguishable from a nearby star — a massive, icy world may be lurking in the shadows, waiting to be discovered by humanity.

And the day that we finally find this elusive planet may be coming soon, thanks to a state-of-the-art telescope that will begin scanning the sky next year.

The solar system has eight official planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. But in recent years, astronomers have proposed that a ninth world, imaginatively nicknamed "Planet Nine," could be hiding in the far reaches of our cosmic neighborhood.

And no, we're not talking about Pluto, which was demoted from full planetary status to "dwarf planet" in 2006. Instead, scientists believe Planet Nine is a gas or ice giant billions of miles farther out than the rest of the planets. If it exists, it could also rewrite our understanding of the solar system's origins and evolution.

Related: How long would it take to reach Planet 9, if we ever find it?

Astronomers have predicted how big this hypothetical world could be, how far away it could lie and even where it should be in its orbit around the sun. Yet actually finding Planet Nine, sometimes called Planet X, has eluded scientists for nearly a decade.

But the hunt for the solar system's potential ninth planet may soon be coming to a close. With the opening of the groundbreaking Vera C. Rubin Observatory in 2025, we may either finally find Planet Nine within the next few years — or rule out the idea for good, experts told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's really difficult to explain the solar system without Planet Nine," Mike Brown, an astronomer at Caltech who proposed the Planet Nine hypothesis along with a colleague, told Live Science. "But there's no way to be 100% sure [it exists] until you see it."

The Planet Nine hypothesis

The unusual orbits of trans-Neptunian objects in and around the Kuiper Belt suggest something massive is hidden in the outer solar system. (Image credit: Getty Images)

The idea of a ninth planet in the solar system was first seeded by the discoveries of Uranus in 1781 and Neptune in 1846, more than 3,000 years after the other planets were first spotted by the Babylonians. These discoveries proved that the solar system was much larger than humanity had once thought and raised the possibility that other worlds were waiting to be discovered.

But other than the now-demoted Pluto, no full-fledged planets beyond Neptune or the Kuiper Belt — a massive ring of asteroids, comets and dwarf planets that orbit the sun beyond Neptune — have shown up since. And as astronomers mapped more of the outer solar system, it seemed increasingly unlikely that they were missing something as large as a planet.

However, a 2004 discovery changed that. Scientists found that Sedna — a potential dwarf planet located beyond the Kuiper Belt — had a weird orbit around the sun. Its unusual trajectory hinted that another large mass in the outer solar system was gravitationally pulling on the miniworld. But without more information, this hypothesis was hard to prove.

Then, in a 2014 study, astronomers announced that they had detected a smaller object in the Kuiper Belt, named 2012 VP113, with an eccentric orbit similar to Sedna's. The findings also hinted that more eccentric trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) were waiting to be found.

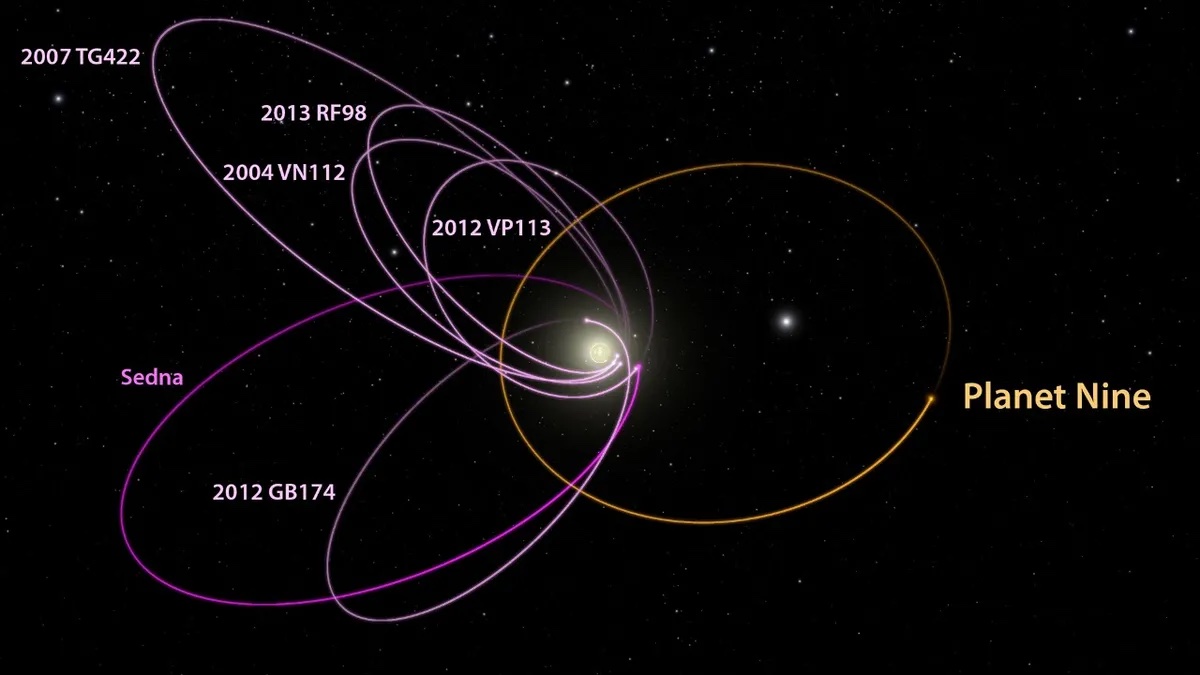

These findings caught the attention of Brown and fellow Caltech astronomer Konstantin Batygin, who noticed that both Sedna and 2012 VP113 had the same "kink" in their orbits. This shared irregularity, which causes the objects to briefly dip below the known planets' plane of orbit, suggested that something — such as an asteroid clump, a dwarf planet or even a full-fledged world — was tugging on these objects.

Related: 8 strange objects that could be hiding in the outer solar system

The orbits of the eccentric TNOs have helped researchers fill in pieces of the Planet Nine puzzle. (Image credit: R. Hurt/JPL-Caltech)

"At the beginning, we didn't say there was a planet because we thought that was a ridiculous thing for there to be," Brown, who also co-discovered Sedna and was instrumental in Pluto's planetary demotion, told Live Science. "But we tried a lot of different things to explain what we were seeing, and nothing else worked."

Even after the pair realized a ninth planet was possible, they decided to sit on their findings until they could come up with another, less-controversial explanation. However, they then found four more TNOs with matching, misshaped orbits, which suddenly made a missing planet look like the most logical explanation.

At the time, the duo calculated that there was just a 2% chance that all six TNOs they had studied shared their orbital oddities thanks to random chance. "And as soon as you see that, you're like, 'Oh crap, there's a planet there,'" Brown said.

So, in 2016, Brown and Batygin published their "Planet Nine hypothesis," which has captured the public's imagination ever since.

Filling in the gaps

Since 2016, Brown, Batygin and others have continued the hunt for Planet Nine. Although they have not found it yet, they have discovered even more eccentric TNOs — bringing the total to 13 and further strengthening the case for Planet Nine.

These discoveries also constrain Planet Nine's potential size, its distance from the sun and its orbital trajectory through the solar system.

"Our best estimates are that it's about seven times more massive than Earth," or anywhere between five and 10 times the mass of our planet, Brown said. This would make it the fifth-most-massive planet in the solar system, behind Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune and Uranus, he added.

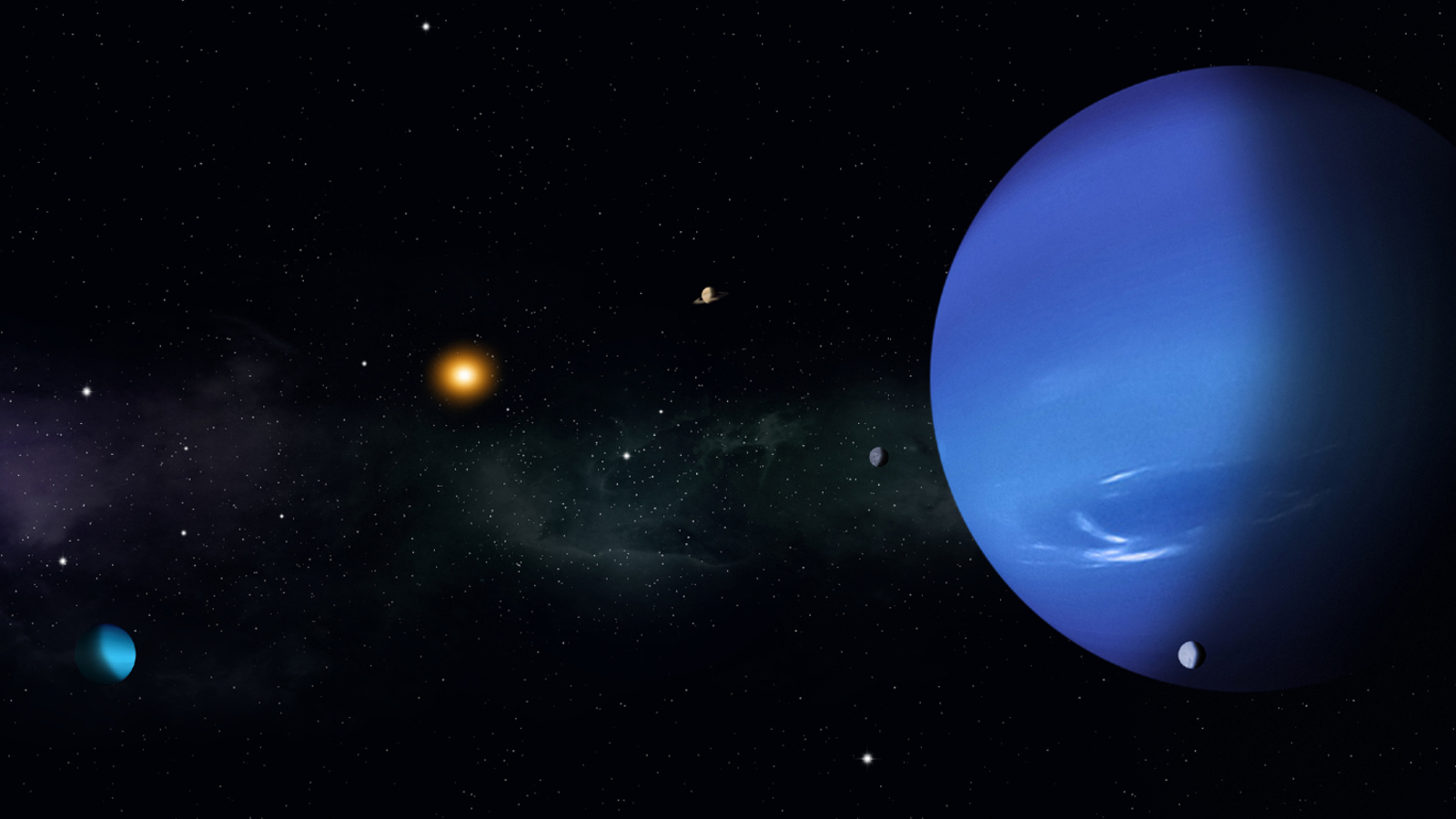

Planet Nine's composition is probably "most like Neptune," due to its distance from the sun, Brown said. "That would put its diameter at something like two times the width of Earth," he added. Some scientists have also suggested Planet Nine could be surrounded by moons, just as the hefty gas giants are.

It's really difficult to explain the solar system without Planet Nine.

Mike Brown, CalTech

Related: Where does the solar system end?

If it exists, Planet Nine is likely around 500 astronomical units away from the sun, on average — meaning it's 500 times farther from the sun than Earth is. This may sound distant, but similarly sized exoplanets have been discovered orbiting alien stars at equally massive distances, showing that this is possible.

This far out, it could take between 5,000 and 10,000 years for Planet Nine to complete a single trip around the sun. Its orbit is probably highly elliptical, so its distance from the sun would vary widely over time. It also likely does not orbit on the same plane as the rest of the planets, which makes it even trickier to find.

Planet Nine's unusual orbit and extreme distance from the sun also raise the possibility that it could be a rogue planet — an interstellar world that was captured by the sun after being ejected from its star system. However, Brown and Batygin believe Planet Nine likely formed alongside the other planets in the solar system.

Based on its distance from the sun, Planet Nine likely has a similar composition as Uranus (left) and Neptune (right). (Image credit: Getty Images)

Is it really out there?

Many astronomers are cautiously optimistic about Planet Nine's existence.

It is "quite likely" that Planet Nine exists, Alessandro Morbidelli, an astronomer at the Côte d'Azur Observatory in France, told Live Science in an email. "There are several indirect lines of evidence in favor of its existence," added Morbidelli, who reviewed Brown and Batygin's 2016 paper before its publication.

David Rabinowitz, an astrophysicist at Yale University, agreed that something is likely out there, and Planet Nine is "the best explanation so far," he told Live Science. The discoveries of additional eccentric TNOs since Planet Nine was first proposed have maintained confidence in this theory, he said.

But not everyone is convinced that Planet Nine is real.

"It's been a roller-coaster! I've gone from thinking it was 90% there to 10% and all around," Sean Raymond, a researcher at the Bordeaux Astrophysics Laboratory in France, told Live Science in an email. "I'm rooting for it to be there, but I'm still agnostic on whether I believe it's there."

Related: What's the maximum number of planets that could orbit the sun?

Doubts about Planet Nine are rooted in alternative potential explanations for the strange behavior seen among TNOs. For instance, the gravitational anomalies Brown and Batygin flagged might be caused by a baby black hole, an invisible giant disk of dust or a historic close encounter with a rogue planet. Alternatively, the TNOs may be evidence that our model of gravity needs to be tweaked.

Others believe the apparent TNO kinks are simply an "observational bias," because it is easier to spot TNOs that are closer to Earth than more distant ones, Samantha Lawler, an astronomer at the University of Regina in Canada and a prominent critic of the Planet Nine hypothesis, told Live Science in an email.

"I believe that there are a lot of really interesting bodies left to discover in the outer solar system," Lawler said. But Planet Nine is not one of them, she added.

However, Brown and Batygin discount the notion that observational bias is creating the illusion of a ninth planet.

"I am as confident as you can possibly be [that Planet Nine exists] until you actually find it," Brown said.

Why haven't we found it?

So, if Planet Nine does exist, why haven't we spotted it yet?

The short answer is that the hidden planet is "very, very far away," Brown said. Light reflected off the planet would be very dim by the time it traveled across most of the solar system (twice), which makes it all but impossible to see.

Initially, the researchers also had no idea where the planet was along its predicted orbital path. That means they've had to study a huge region of the sky to look for this faint body — akin to trying "to find a single white whale in an ocean," Brown said.

Related: How many times has Earth (and the other planets) orbited the sun?

So far, researchers have analyzed thousands of images from multiple sky surveys along Planet Nine's proposed orbital pathway, looking for objects that move over time, Brown said.

Data from the Pan-STARRS-1 observatory in Hawaii has already narrowed down where Planet Nine may be hiding. (Image credit: Rob Ratkowski / Harvard Center for Astrophysics)

Unfortunately, the night sky is teeming with bright, moving objects, such as comets, so the researchers have to sort through "a lot of garbage" to find the planet, Brown added.

In their most recent work, Brown and Batygin analyzed data from the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS) at Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii and confidently ruled out around 78% of the suspected orbital pathway as possible hiding places for the planet.

This narrowed down Planet Nine's location to somewhere in the most distant 22% of its orbital pathway. Unfortunately, telescopes like Pan-STARRS are not powerful enough to properly search this space.

When will we find it?

If Planet Nine is hiding in the most distant reaches of its orbit, we'll need a telescope powerful enough to spot it.

Brown and Batygin have already begun analyzing data from Japan's Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, which has a better chance of finding the planet than Pan-STARRS does. But if this survey fails to complete the job, they will turn to the forthcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which is currently under construction in Chile.

This ground-based telescope, which will be equipped with the world's largest digital camera, will let researchers peer farther into the solar system than any of its predecessors allowed, similar to how the James Webb Space Telescope has enabled researchers to look farther across the observable universe than ever before.

The observatory is currently slated to open in late 2025.

Astronomers think the forthcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile will finally allow them to spot Planet Nine. (Image credit: Olivier Bonin/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

Related: 5 space discoveries that scientists are struggling to explain

With the help of the state-of-the-art telescope, Planet Nine could be found within the next two years, Brown said. However, he also joked that he has been saying the same thing every year since 2016.

Raymond and Rabinowitz both agreed that Planet Nine could be found within a year after the Rubin Observatory comes online. If the telescope cannot find the planet within the first few years, however, "then the hypothesis is pretty much dead," Raymond said.

But Morbidelli and Rabinowitz pointed out that even if the telescope does not find the planet immediately, it could still identify more TNOs, which would help show if the theory is viable.

Why does Planet Nine matter?

If Planet Nine is discovered, space agencies will likely send probes to visit the distant world. (Image credit: Anton Petrus via Getty Images)

Although scientists remain divided over Planet Nine's existence, one thing they all agree on is that actually finding the elusive world would likely be the biggest solar system discovery of the century.

It would be a "remarkable" find, Raymond said. It would also be "huge" for our understanding of the solar system's origins and evolution, he added.

Observing the planet could also teach us more about the formation and evolution of giant planets, Morbidelli said. This would not only help us learn more about planets in the solar system but also shed light on thousands of giant exoplanets around distant stars.

If space agencies like NASA send probes to fly close to the planet, they could also reveal more clues about the solar system's past.

"It'll have many secrets that will be unlocked by studying it in detail," Brown said.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior, evolution and paleontology. His feature on the upcoming solar maximum was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the National Council for the Training of Journalists (NCTJ) Awards for Excellence in 2023.