The battle of Ipsus - Livius (original) (raw)

Prelude

The empires of the Diadochi before the battle of Ipsus (301)

After the death of Alexander the Great (323), his generals started to fight each other. At first, the most successful of these were Antigonus Monophthalmus ('the One-Eyed') and his son Demetrius, who fought the Third Diadoch War against their rivals Cassander (in Macedonia and Greece) and Ptolemy Soter (in Egypt). However, in the Babylonian War (311-309), they were unable to prevent that their eastern satrapies were taken over by Seleucus Nicator, who slowly started to build an empire of his own in the east.

In 307, the Fourth Diadoch War broke out. Again, Antigonus and Demetrius were fighting against Cassander and Ptolemy, who were now supported by Lysimachus, the ruler of Thrace, who invaded Asia Minor and captured Sardes and Ephesus. The troops of Demetrius, who were in Thessaly fighting Cassander, crossed the Aegean Sea and started on a march through Asia. At the same time, Cassander crossed the Hellespont, hoping to support Lysimachus, and Antigonus moved from Syria to Asia Minor, hoping that he and his son could defeat Cassander and Lysimachus in one decisive battle.

Ptolemy stayed out of this conflict. It is true that he invaded Syria to detract Antigonus, but when he learned that Antigonus had been victorious, he returned. As it turned out, the report was incorrect, but Lysimachus was left on his own, and Demetrius and Antigonus were able to isolate him near Ipsus in Phrygia.

Sources

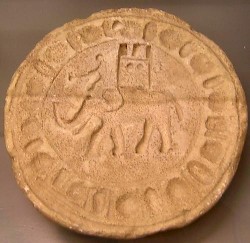

War elephant

The main description of the fight at Ipsus is in Plutarch's Life of Demetrius, 28-29. It is quoted below. The name of the battlefield is mentioned by Appian of Alexandria (Syrian Wars, 55). Several details can be found in Book 21 of the Library of World History by Diodorus of Sicily. All three sources appear to go back on Hieronymus of Cardia's History of the Successors. The Babylonian text that is known as the Antiochus and India Chronicle (BCHP 7) may be related to the Ipsus campaign.

Battle

Briefly before battle was joined, unexpectedly Seleucus appeared on the scene and joined Lysimachus and Cassander, together with his son Antiochus and a large army and four hundred war elephants. This changed the entire situation. Plutarch offers some numbers, but the appear to be inflated. Still, it seems reasonably certain that after Seleucus' arrival, the armies were near equal in size.

The battle started when Demetrius, commanding Antigonus' cavalry, attacked Seleucus' son Antiochus and drove him from the battlefield. At the same time, Antigonus the One-Eyed, commanding the phalanx, came to grips with the infantry of the allies. Because Demetrius was away, Antigonus' flank was now unprotected, and when Seleucus threatened to attacked this wing, a part of Antigonus' soldiers surrendered. Still, Antigonus expected to be saved by his on, but when Demetrius tried to return to the battlefield, he found his way blocked by Seleucus' elephants. According to Plutarch, Antigonus was killed by a hail of spears, which suggests that he was killed by light infantry. Understanding that everything was lost, Demetrius retreated with a small army. Diodorus adds that Antigonus received a royal burial.

Consequences

Antigonus' attempt to reunite Alexander's empire had already failed during the Babylonian War; the battle of Ipsus did nothing to change that. However, it meant the end of about twenty years of war. Numismatical evidence strongly suggests that the money that has once been seized by Alexander in the Persian capitals, was running out. Ipsus was the last battle because Seleucus, who owned the treasures, was now running out of funds.

Coin of Seleucus Nicator

New kingdoms were created within the old one: Ptolemaic Egypt, the Seleucid Empire, and Macedonia. Antigonus' possessions (Syria and Anatolia) were divided between Lysimachus (who received the western part of Anatolia), Cassander (who gave Cilicia and Lycia to his brother Pleistarchus), and Seleucus, who was to receive Syria, but had to discover that the southern part of it, Coele Syria, had been snatched away by Ptolemy. Lack of funds prevented Seleucus' attack on Ptolemy, but the cause for new conflicts was ther (the Syrian Wars). Finally, Ariarathes II seized Cappadocia.

Literature

- François de Callataÿ, "Les trésors achéménides et les monnayages d'Alexandre" in Revue des Études Anciennes 91 (1989) 259-276

- V.K. Golenko, "Notes on the coinage and currency of the early Seleucid state" in: Mesopotamia 28 (1993) 71-167

The account by Plutarch

The following text is Plutarch's account of the battle, from his Life of Demetrius, 28-29. The translation was made by John Nalson and belongs to the Dryden series.

[28] A general league of the kings, who were now gathering and combining their forces to attack Antigonus, recalled Demetrius from Greece. He was encouraged by finding his father full of a spirit and resolution for the combat that belied his years. Yet it would seem to be true, that if Antigonus could only have borne to make some trifling concessions, and if he had shown any moderation in his passion for empire, he might have maintained for himself till his death and left to his son behind him the first place among the kings. But he was of a violent and haughty spirit; and the insulting words as well as actions in which he allowed himself could not be borne by young and powerful princes, and provoked them into combining against him. Though now when he was told of the confederacy, he could not forbear from saying that this flock of birds would soon be scattered by one stone and a single shout.

He too the field at the head of more than 70,000 foot, and of 10,000 horse, and 75 elephants. His enemies had 64,000 foot, 500 more horse than he, elephants to the number of 400, and a 120 chariots. On their near approach to each other, an alteration began to be observable, not in the purposes, but in the presentiments of Antigonus. For whereas in all former campaigns he had ever shown himself lofty and confident, loud in voice and scornful in speech, often by some joke or mockery on the eve of battle expressing his contempt and displaying his composure, he was now remarked to be thoughtful, silent, and retired.

He presented Demetrius to the army and declared him his successor; and what every one thought stranger than all was that he now conferred alone in his tent with Demetrius; whereas in former time he had never entered into any secret consultations even with him; but had always followed his own advice, made his resolutions, and then given out his commands. Once when Demetrius was a boy and asked him how soon the army would move, he is said to have answered him sharply, 'Are you afraid lest you, of all the army, should not hear the trumpet?'

[29] There were now, however, inauspicious signs, which affected his spirits. Demetrius, in a dream, had seen Alexander, completely armed, appear and demand of him what word they intended to give in the time of the battle; and Demetrius answering that he intended the word should he 'Zeus and Victory,' 'Then,' said Alexander, 'I will go to your adversaries and find my welcome with them.'

And on the morning of the combat, as the armies were drawing up, Antigonus, going out of the door of his tent, by some accident or other stumbled and fell flat upon the ground, hurting himself a good deal. And on recovering his feet, lifting up his hands to heaven, he prayed the gods to grant him, 'either victory, or death without knowledge of defeat.'

When the armies engaged, Demetrius, who commanded the greatest and best part of the cavalry, made a charge on Antiochus, the son of Seleucus, and gloriously routing the enemy, followed the pursuit, in the pride and exultation of success, so eagerly, and so unwisely far, that it fatally lost him the day; for when, perceiving his error, he would have come in to the assistance of his own infantry, he was not able, the enemy with their elephants having cut off his retreat.

And on the other hand, Seleucus, observing the main battle of Antigonus left naked of their horse, did not charge, but made a show of charging; and keeping them in alarm and wheeling about and still threatening an attack, he gave opportunity for those who wished it to separate and come over to him; which a large body of them did, the rest taking to flight.

But the old King Antigonus still kept his post, and when a strong body of the enemies drew up to charge him, and one of those about him cried out to him, 'Sir, they are coming upon you,' he only replied, 'What else should they do? But Demetrius will come to my rescue.' And in this hope he persisted to the last, looking out on every side for his son's approach, until he was borne down by a whole multitude of darts, and fell. His other followers and friends fled, and Thorax of Larisa remained alone by the body.