Ofonius Tigellinus - Livius (original) (raw)

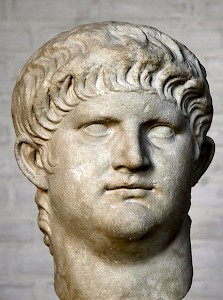

Nero

History has been unkind towards Tigellinus, who was one of the closest and most loyal advisers of the emperor Nero (54-68) during the second half of his reign. During its first half, the young emperor had senatorial advisers like the philosopher Seneca, but when Nero grew older and embarked upon a more independent course, there was also room for men of lower social rank. Unfortunately, Nero was incapable of coping with his immense power and, to make matters worse, Rome was destroyed by fire in 64, a disaster that better emperors would also have found hard to deal with. Nero became more tyrannical and in 68, insurrections in Gaul, led by Julius Vindex, and Spain, led by Servius Sulpicius Galba, resulted in his downfall and suicide. As history was written by senators like Tacitus, many errors of Nero were assumed to be those of his non-senatorial advisers.

Almost all information about Tigellinus is biased. Tacitus states that Tigellinus "was of humble birth and had a vicious childhood". Another source, an ancient commentary on the First Satire of Juvenal, informs us that Tigellinus' family was from Agrigentum on Sicily, but that his father had lived in Scyllaceum, a port in the "toe" of Italy. The commentator presents this as an exile, which may or may not be true.

The family may have been impoverished, but was not so poor that it no longer had the means to give the young Tigellinus a proper education. He had access to influential families like that of Marcus Vinicius (consul in 30) and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (consul in 32), who were married to the daughters of Germanicus, Livilla and Agrippina Minor. After their brother Caligula had succeeded Tiberius as emperor, the ladies fell into disgrace (39). Agrippina and was exiled to one of the Pontic islands and, according to Cassius Dio, Tigellinus was also sent away, on a charge of having had a sexual relation with Agrippina.note[Cassius Dio, Roman History 59.23.9] As we will see in a moment, this particular detail may have been more than just gossip.

The commentator of Juvenal tells that Tigellinus was now active as a merchant in Greece, but received an inheritance that enabled him to live a less dangerous life. The emperor Claudius (41-54) allowed him to return to Italy under the condition that he would not visit the imperial palace; this unusual condition may be explained from the fact that Claudius had in the meantime married Agrippina, and did not want to meet her former lover.

Tigellinus invested his new fortune in land in the "heel" of Italy, and befriended Lucius, the son of Agrippina and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus; they appear to have shared a passion for horse racing. This friendship turned out to be the road back to court. In 50, Agrippina convinced her husband to adopt Lucius and appoint him as successor. To strengthen his claim to the throne, Claudius' daughter Octavia was forced to marry her adopted brother - an extremely unhappy marriage that was to end in disaster. However, in 54, Lucius became emperor; he was now called Nero.

In c.60, Tigellinus was appointed as prefect of the vigiles, the fire-brigade of Rome. In the six intervening years, he must have occupied other offices and must have become a member of the equestrian order, but the details are unknown, although it is likely that he obtained some military experience, for example as commander of an auxiliary unit or as tribune in a legion, because in 62, he succeeded Burrus as praetorian prefect, and it would be foolish to make a man without experience in the army commander of the imperial guard. Because the prefect of the guard was dangerously powerful, Nero decided to appoint two commanders; therefore, Tigellinus had to share his office with Faenius Rufus, who was replaced in 65 by Nymphidius.

More or less at the same time, Seneca lost influence after accusations - Tacitus suggests that they were made by the new prefects of the guard - that he was too much interested in making money. There was certainly an element of truth in these charges, but Nero refused to dismiss his adviser, who voluntarily stepped back.

If we are to believe Tacitus, Tigellinus "tempted Nero to every form of wickedness and even ventured on some crimes without his knowledge". It is probably better to say that as commander of the guard, he had to do the dirty work. In 62, he made sure that two exiled senators lost their lives, and when Nero announced that he wanted to marry his lover Poppaea, Tigellinus constructed the evidence that Nero's lawful wife Octavia had been unfaithful. He was ruthless, but that was his job. In 65, he proved his value by suppressing the conspiracy of Piso.

Tigellinus now became very influential. After the suppression of the conspiracy, he was awarded with ornamenta triumphalia and a statue on the Palatine, an unheard-of honor for a member of the equestrian order that will have done little to make him popular with Rome's senators. As was common, he sometimes used his influence for personal purposes. His son-in-law Cossutianus Capito had been convicted because of extortion and was expelled from the Senate, but Tigellinus came to his assistance. On another occasion, he saved the life of a daughter of a senator named Titus Vinius.

Tacitus presents this latter act as nothing else than a criminal's trick: Tigellinus had seen how Nero was losing control of the situation, and had created an exit for himself. This is not likely: Tigellinus owed everything to the emperor and had nothing to gain from the end of Nero's reign. His fate was inseparable from the emperor's. Once Nero fell, he would fall. Tacitus' interpretation tells more about him than about Tigellinus. Another example of innuendo is Tacitus' claim that, because the great fire of Rome in 64 flared up again in a part of Rome owned by Tigellinus, the praetorian prefect was an arsonist.

In 67, Nero decided to visit Greece, where special Olympic Games were organized; he won all contests. Tigellinus accompanied the emperor and may have played a role when the famous general Corbulo, who had been invited to come to Greece as well, was ordered to commit suicide.

During the absence of Nero, Rome was controlled by a freedman named Helius and by Tigellinus' colleague Nymphidius, who expanded his control of the imperial guard. After Nero's return at the end of the winter of 67/68, Tigellinus was obviously the lesser of the two prefects.

This lack of power saved his life, because he was not forced to take responsibility during the final months of Nero's reign. In the spring Gaius Julius Vindex revolted in Gaul, and although he was defeated by the loyal general Lucius Verginius Rufus, the next revolt was more successful: the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, Servius Sulpicius Galba marched on Rome, where Nymphidius bribed the guard to switch sides. Tigellinus, who claimed to be ill, was not responsible for this treason. Nero fled and committed suicide, assisted by his freedman Epaphroditus.

During the reign of Galba, Titus Vinius protected Tigellinus - after all, Tigellinus had once saved the life of his daughter. This protection could not last forever, because Galba had been slow to pay the imperial guard to which he owed his throne, and was lynched by the men who should have protected him. The new ruler was Marcus Salvius Otho, who immediately ordered Tigellinus to commit suicide at the spa of Sinuessa. Mercilessly, Tacitus adds that "in an atmosphere of lechery, kissing and nauseous hesitations, Tigellinus finally slit his throat with a razor, and crowned a disreputable life with new infamy by quitting it too late".

This was the end of a man who was loyal to his emperor to the very end, and was, for this reason, detested by the Senate.