Sardes - Livius (original) (raw)

Sardes or Sardis (Greek Σάρδεις): capital of Lydia, one of the most important sites in western Turkey, one of the "seven churches" of the Revelation of John, modern Sartmustapha.

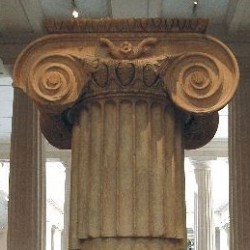

Lydian Capital

The citadel

According to the Greek researcher Herodotus of Halicarnassus, who often mentions Sardes and is our main source for its early history, the city was the capital of ancient Lydia, the kingdom founded by king Gyges (r. c.680-c.644). The city is older - there are finds that date back to the Bronze Age - but archaeologists have confirmed that Sardes rose to prominence in the mid-seventh century, the age of Gyges. After the Cimmerians had raided Anatolia and had destroyed the Phrygian Empire, Sardes became a more impressive town.

The source of its wealth was the fertile plain north of the city, which allowed a large population to be fed. Another important source of wealth was the Pactolus, a little river that contained gold dust. It is probably no coincidence that the world's first coins were minted in Sardes.

Lydian market

The last king of independent Lydia was the proverbially rich Croesus. In his age, Sardes was a large city with trade contacts with Greece in the west and the Black Sea area in the north. Archaeological research has brought to light the Lydian market area and has shown that the temple of Artemis/Cybele, which was to become one of the most splendid monuments of Asia Minor, already existed in these days. The citadel was occupied as well, while the Lydian kings were buried directly north of the city, at Bin Tepe.

After c.547, the Persian king Cyrus the Great captured Sardes (more...) and made it the western capital of his empire. From here, the Persians ruled the Yaunâ, notorious pirates and clever salesmen, better known to us as the Greeks.

Persian Capital

The "Mistress of the animals": slab from the original temple of Artemis. The archer who is partly visible to the right, must be Heracles.

At the beginning of the fifth century, the Yaunâ revolted and destroyed the lower part of Sardes.note[Herodotus, Histories 5.100-102.] The citadel remained uncaptured and the Persians were able to retaliate: many Greeks who had taken part in the raid, perished on their way back home,note[Herodotus, Histories 5.99-102.] and the Persians brought the war to the Greek homeland in the years 492-479.

Eventually, their expedition forces were defeated, but at least, the Greeks recognized that they should leave Sardes to the Persians, and during the next century and a half, Sardes was the place from which gold was sent to the Yaunâ, who were thus divided and controlled. Diplomatic control could be even more direct: in 387/386, Sardes was the place where the Persian nobleman Tiribazus dictated the terms of the King's Peace to the Greeks.note[Xenophon, Hellenica 5.1.30.]

The city, which was connected with the Persian heartland by the age-old Royal Road, is not very well-known. It was the capital of one of the main satrapies, and we know that there was a palace on the citadel, but archaeologists have, until now, not often focused on this period. Yet, the tomb of one official has been identified on the western slopes of the citadel, and from literary sources we know that the temple of Cybele/Artemis was an important monument. Other native deities were Sabazius and Argistis, while Greek and Persian cults were popular as well.

Hellenistic City

Pactolus, the gold river

In the spring of 334, the Macedonian king Alexander the Great defeated the Persian garrison of Asia Minor on the banks of the Granicus. Sardes surrendered almost immediately; its last satrap, a man named Mithrenes, became one of the grand lords at the court of Alexander. The city received several privileges.note[Tacitus, Annals 3.62.] For Sardes and Lydia, this was the beginning of an unquiet period, marked by nearly continuous warfare.

Initially, it was part of the empire of Antigonus Monophthalmus, but after the battle of Ipsus (301 BCE), it was taken over by Lysimachus, who lost the city to Seleucus I Nicator in the battle of Corupedium (281), which was fought on the plain north of the city. Later, the town was one of the residences of Antiochus Hierax, a Seleucid prince who acted rather independently. In a series of conflicts in the 240s, he managed to stand his ground against his brother, Seleucus II Callinicus, but the main center of western Asia was slowly moving to Pergamon.

History repeated itself after 223 BCE, when the Seleucid general Achaeus restored order, started to act independently, and was attacked by an army from the central government, commanded by king Antiochus III the Great, who captured Sardes in 213.

One of the Seleucid victors announced the rebuilding of the sanctuary of Artemis as a Greek temple. However, the blueprint was too grandiose and the temple was not finished.

Antiochus was defeated by the Romans in the Syrian War (192-188), and the victors awarded Sardes to the Pergamene king Eumenes II Soter, their ally. In 175 BCE, construction of the temple of Artemis was resumed, but again, it was impossible to finish the sanctuary. It was more than three centuries later, during the reign of the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius (r.138-161 CE), that the building was finally complete. By then, however, the goddess Artemis had been forced to share her home with the emperor. It was now a double sanctuary.

Sardes, Temple of Artemis and citadel Sardes, Temple of Artemis and citadel |

Temple of Artemis, column Temple of Artemis, column |

Sardes, Temple of Artemis, Commemorating a venatio Sardes, Temple of Artemis, Commemorating a venatio |

Sardes, Temple of Artemis and citadel Sardes, Temple of Artemis and citadel |

|---|

Roman City

Rome had taken over the city in 133 BCE, when the last king of Pergamon, Attalus III Philometor, had died and had bequeathed his kingdom to the Romans. Sardes was, by now, a Greek city, with a gymnasium, Greek-style sanctuaries (although sometimes unfinished), Greek city institutions, a theater, a stadium, and inscriptions in the Greek language.

Gymnasium

As part of the Roman Empire, Sardes was loyal to the Senate, fighting against king Mithridates VI Eupator during the First Mithridatic War (89-85). To its heroic behavior, the city owed certain privileges, such as a special position in the provincial council, and an important law court. When the city was destroyed by an earthquake in 17 CE, the emperor Tiberius awarded no less than ten million sesterces for its reconstruction, and told the Sardians that they did not have to pay taxes for five years.note[Tacitus, Annals 2.47.]

Among the buildings of this age are a temple for Augustus and Gaius Caesar, a temple for Tiberius, baths, and an aqueduct (built during the reign of Claudius). The emperor Septimius Severus (r.193-211) restored the gymnasium.

Next to the gymnasium was the synagogue, which dates back to the reign of the emperor Severus Alexander (r.222-235). There were no separate arrangements for women, which suggests that they worshiped together with the men, a practice frowned upon in several other parts of the Mediterranean world.

Sardes, Synagogue, Table, Eagle Sardes, Synagogue, Table, Eagle |

Sardes, Synagogue Sardes, Synagogue |

Sardes, Synagogue Sardes, Synagogue |

Sardes, synagogue, Torah ark Sardes, synagogue, Torah ark |

|---|

The Jewish presence in Lydia, however, is much older. Flavius Josephus quotes a document from the authorities of Sardes, in which permission is granted to build a synagogue.note[Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 14.259-261.] It has even been thought that there were Jews in Sardes as early as the third quarter of the sixth century BCE (if the Sepharad mentioned in Obadiah 20 are indeed the Jews of Sfard, the original name of Sardes). Another indication for a Jewish community is the presence of Christians, which are mentioned in the Revelation of John 3.1-5. They must have been converted Jews.

Late Antiquity

In the fourth century, Sardes was still an important city, where weapons were produced for the Roman army. It may have had as many as 100,000 inhabitants, was sufficiently wealthy to redecorate its market, gymnasium, and synagogue, and build at least two basilicas. There are some Byzantine remains.

Sardes was captured by the Sasanian king Khusrau II in 616, an event that marks the decline of the city. The citadel, however, remained in use for centuries to come.