The Cambrai operations, 1917 (Battle of Cambrai) - The Long, Long Trail (original) (raw)

20 November – 30 December 1917: the Cambrai operations. A British attack, originally conceived as a very large scale raid, that employed new artillery techniques and massed tanks. Initially very successful with large gains of ground being made, but German reserves brought the advance to a halt. Ten days later, a counter-attack regained much of the ground. Ultimately a disappointing and costly outcome, but Cambrai is now seen by historians as the blueprint for the successful “Hundred Days” offensives of 1918.

“The Battle of Cambrai ranks as one of the most thrilling episodes of the whole war. Tanks at last came into their kingdom. The notion that the Hindenburg Line was impregnable was exploded”.

Captain Stair Gillon: The Story of the 29th Division: a record of gallant deeds.

Cambrai was a splendid success …

There is a trend among military historians to assign the eventual military defeat of Germany to well planned and co-ordinated assaults by the Allies, in which industrial might and the hard learning of four years of war combined to great effect. Beginning on 8 August 1918, the British Expeditionary Force undertook a series of large scale attacks on multiple fronts in which artillery, armour, aircraft and infantry operated effectively together in “all arms” battles. The opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917 is often identified as the first demonstration of the sophisticated techniques and technologies required to effect such a battle. On that day, the British attack broke deeply and quickly into apparently impregnable defences with few casualties. This early result was widely regarded as being a great and spectacular achievement, so positive was it in comparison with the recent ghastly slog to Passchendaele. The Daily Mail called it a “Splendid Success” and headlined on 23 November with “Haig through the Hindenburg Line”.

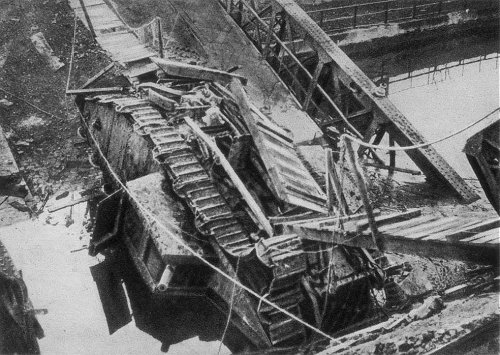

“Flying Fox” British tank “Flying Fox”, stuck fast and blocking the key canal bridge at Masnieres.

British tank “Flying Fox”, stuck fast and blocking the key canal bridge at Masnieres.

… until it all went wrong

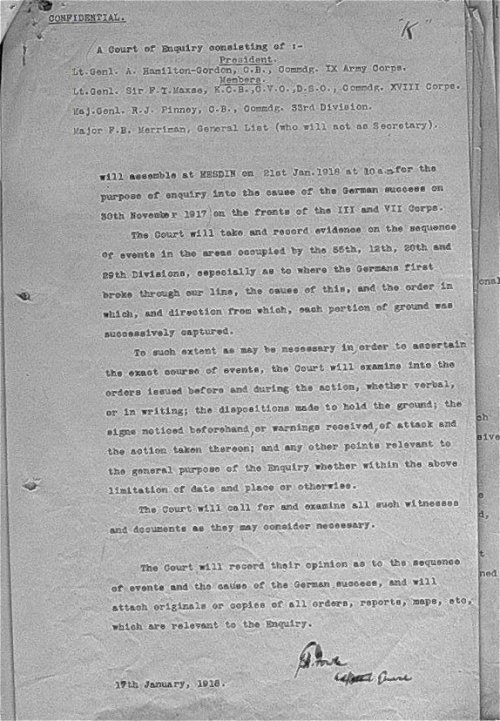

Yet two months later, a court of enquiry convened at Hesdin to examine what had gone wrong at Cambrai. This unusual step was taken after questions had been asked by the War Cabinet, following a German counter attack that had apparently come as a surprise and against which the British forces lost ground and suffered heavy losses. Initial success, even if containing the seeds of a war winning approach that would germinate on the Santerre plateau in August 1918, had been short lived, and there was bitter disappointment at the net result. One respected commentator, a former junior officer, said that “_Cambrai was a highly speculative gamble which I find inexplicable, so out of character is it with the rest of Haig’s career, not because it was inventive but because it was haphazard, not thought through_” and that it was a “_harum-scarum affair, ill-planned and feebly directed, yet in military history it stands as the most significant battle of the First World War_“. [Charles Carrington, Soldier from the wars returning (London: Hutchinson & Co, 1965), pp.205-6]

Inception

When the Official History of the battle was being compiled, Lieutenant General Sir Launcelot Kiggell, Haig’s Chief of General Staff in late 1917, said that he could give no definite date as to the first discussion of Cambrai, nor would any written record be found as all was verbal at the inception of the campaign. He recalled that General Hon. Sir Julian Byng, commanding Third Army, had come to see Haig around three months before the attack, asking to be allowed to make a surprise assault at Cambrai. Thereafter, according to Kiggell, the plan “just growed”.

Byng would have been aware of an existing arrangement, prepared in June 1917 by Fourth Army’s III Corps after Haig had ordered it to examine breaking the German defences in the Cambrai area. Some preparations had already been made in accordance with this plan before Third Army took over the Cambrai front in early July. It required a methodical “bite and hold” advance in four stages using six Divisions. This approach probably seemed unimaginative to the characteristically optimistic Byng, but it was conventional by the standards of the latter half of 1917.

It appears that it was the enthusiasm of the Tank Corps and the artillery that swayed opinion at GHQ and Third Army and built support for the “harum-scarum” operation that eventually took place. Brigadier General Hugh Elles, commanding the Tank Corps in France, and his chief staff officer, Lieutenant Colonel John Fuller, visited both the Montreuil General Headquarters and that of Third Army at Albert several times in August 1917. They made a convincing case that with growing strength in France, the Corps should not be frittered away at Ypres but used collectively to punch a hole into the enemy defences. Cambrai, being on relatively undamaged rolling chalk land, would be ideal although they favoured an attack in French Flanders, which GHQ vetoed. Elles and Fuller talked of a short, limited heavy raid designed to cause damage and chaos – a tactical operation designed to kill, not capture ground. Major General John Davidson, Chief of Operations staff at GHQ, was taken with the idea as was Byng, already mulling over such an operation at Cambrai. Independently and at the same time, IV Corps in Byng’s Army had developed a scheme for a surprise attack using unregistered artillery. The Tank Corps much approved of the idea, for it would avoid the devastation of ground that had caused so much difficulty for the machines at Ypres.

Hindsight: The genesis of Cambrai can be traced easily enough through these developments in the summer of 1917. Enthusiasts, learning from prior disappointments, were developing new ideas and advocating their use, finding in Byng an equally enthusiastic and respected figure who achieved a consensus of support at the highest levels of command. The pace at which Third Army created the plan, then trained and assembled their forces and executed a successful attack indicates a growing maturity of the organisation and processes required to make this so. Yet the improvised, experimental nature of Cambrai was a root cause of the lack of planning and feeble direction highlighted by Charles Carrington. The sketchy nature of the plan is to some extent forgivable, for here was a chance to leave the disappointments of Passchendaele behind and do something audacious. What is much more difficult to understand is the strategic need to carry out this operation at all, the objective of employing these ideas at this place and at this time, and the evident lack of thought about potential outcomes.

Why here, why now?

Why Cambrai at all? Its strategic significance as the target of a surprise attack is far from clear. After falling to the Germans in 1914, Cambrai had become an important railhead, billeting and headquarters town. It lay at a junction of railways connecting Douai, Valenciennes and Saint-Quentin, and as such was on the supply routes coming in from Germany and the northern and eastern industrial areas of occupied France, as well as a lateral route down which men and material could be moved along the western front. It was also on the Saint-Quentin canal, from which the front could be supplied along the River Scheldt with which it was contiguous. As a military target, Cambrai would be a useful capture to deny the enemy a key part of his communication system. But it lay behind a formidable defensive position. Assuming this could be breached, it would also be most difficult to fight through an industrial town, as had been recognised in 1915 when attacks on the not dissimilar Lens were avoided. It would seem that Cambrai was chosen at least as much because it was in Byng’s area and that the Tank Corps were convinced the ground was to their advantage, as for any other sound military reason.

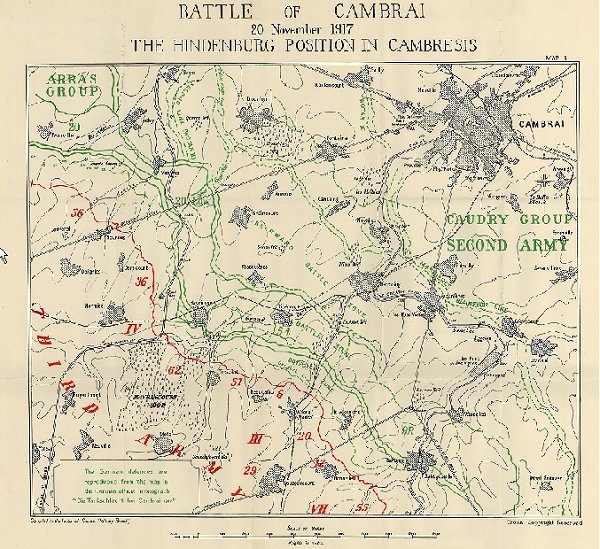

The Hindenburg Line By 1917, Cambrai had become one of the most important railheads and HQ towns behind the German lines. In front of it lay the immensely powerful Siegfried Stellung – better known to the British as the Hindenburg Line. So strong was the defensive position here that German Divisions decimated during Third Ypres were sent here to recuperate and refit. It included two lines of fortifications, with barbed wire belts tens of yards wide, concrete emplacements and underground works. A third parallel line was also under construction. The map inset above shows the German withdrawal from he Somme to the Hindenburg Line in spring 1917 and the main defensive position faced by the British at Cambrai..

By 1917, Cambrai had become one of the most important railheads and HQ towns behind the German lines. In front of it lay the immensely powerful Siegfried Stellung – better known to the British as the Hindenburg Line. So strong was the defensive position here that German Divisions decimated during Third Ypres were sent here to recuperate and refit. It included two lines of fortifications, with barbed wire belts tens of yards wide, concrete emplacements and underground works. A third parallel line was also under construction. The map inset above shows the German withdrawal from he Somme to the Hindenburg Line in spring 1917 and the main defensive position faced by the British at Cambrai..

The British force at Cambrai

Byng’s growing enthusiasm, even with Haig’s support, was insufficient to summon up forces for the operation while Third Ypres was still underway. One GSO1 staff officer at GHQ – Brigadier General E. N. Tandey – recalled a meeting in September 1917:

“I was called one afternoon, in the absence of the MGGS, to the Chief’s chateau. I found him alone with General Byng. He quietly announced that as he intended to attack with the Third Army at Cambrai with tanks in early November … he wanted to tell General Byng exactly which Divisions he could have for the purpose. He told me that he had offered him 2 or 3 which he named. I remember my quandary as I had to tell him that none of those he had selected (and one or two others he also mentioned) … would be fit to go into the attack by the date named, as they would not have had the minimum time necessary to absorb their reinforcements without which they could not be battle formations. I thought he would eat me”.

Kiggell counselled that there were insufficient troops to undertake both operations and Third Army’s action was placed on hold. It was not until 13 October that Haig gave his approval, and another two weeks after that before Byng briefed his Corps commanders.

The Hindenburg Line in the Cambresis (Cambrai area) From the British Official History .

From the British Official History .

The plan of attack

In Third Army orders – codenamed Operation GY – issued on 13 November 1917, the attack was defined as a_coup de main_, “to take advantage of the existing favourable local situation” where “surprise and rapidity of action are … of the utmost importance”. It was also to be a deep attack on a 10,000 yard (5.6 mile) front that would be “widened as soon as possible”. Once the key German Masnieres-Beaurevoir line had been breached by III Corps, the cavalry would pass through, reach around to isolate Cambrai from the rear and cut the railways leading from it. Haig would later say that the purpose of the attack was to compel the enemy to withdraw from the salient between the Canal du Nord and the Scarpe, although the objectives must be achieved within 48 hours before strong enemy reserves could come into play. So the high speed and short tactical operation had somehow become one of seizing and holding ground, and while not quite a plan for strategic breakthrough – there were never enough reserves to exploit a breakthrough – the orders had faint resemblance to the original concepts.

The strong defences of the Hindenburg Line This is a map of a small part of the Hindenburg Line, north west of Flesquieres. The position to be attacked consisted of two trench systems, with deep barbed wire defences in front of each. The trenches were dotted with concrete blockhouses containing machine gun posts, signals stations, infantry shelters and so on.

This is a map of a small part of the Hindenburg Line, north west of Flesquieres. The position to be attacked consisted of two trench systems, with deep barbed wire defences in front of each. The trenches were dotted with concrete blockhouses containing machine gun posts, signals stations, infantry shelters and so on.

Dawning of a new era

The operational factors that led to initial British success were

> the ability to maintain surprise

> emphasis on neutralisation of enemy firepower

> adequate weight of artillery and deployment of well trained if hardly fresh troops.

A contributory factor was intelligence of the enemy’s dispositions and ability to reinforce and counter attack, which appears to have been reasonably accurate. Things were also helped by a corresponding intelligence failure on the part of the German Second Army.

Cambrai battle lines This is a map of a small part of the Hindenburg Line, north west of Flesquieres. The position to be attacked consisted of two trench systems, with deep barbed wire defences in front of each. The trenches were dotted with concrete blockhouses containing machine gun posts, signals stations, infantry shelters and so on.

This is a map of a small part of the Hindenburg Line, north west of Flesquieres. The position to be attacked consisted of two trench systems, with deep barbed wire defences in front of each. The trenches were dotted with concrete blockhouses containing machine gun posts, signals stations, infantry shelters and so on.

Dawning of a new era: artillery

Previous British offensives in France had characteristically opened with a long bombardment of the German positions, with the intention of destroying barbed wire defences, trenches and strong points to allow as unhindered as possible a passage for the infantry to capture the position. Even before bombardment opened, guns would be registered by the firing of observed ranging shots, with adjustments being made to line, range and shell fuze setting to ensure that firing would be accurate. These methods had proven to have several disadvantages, not least being that there was no concealment of imminent attack.

By mid 1917, a series of technological developments had made it possible to fire accurately without registering. The new technologies and associated methods included accurate survey of the gun position; mapping of enemy positions through aerial and ground observation; calculated reckoning of invisible enemy battery positions through triangulation on sources of sound and gun flash; advanced local meteorology and understanding of the effect of weather on the flight of the shell; improved reliability of munitions through improved quality control in manufacture; calibration of the wear condition of the gun barrel, and the training of battery officers and NCOs in the mathematical methods required to turn this complex set of factors into physical settings of the fuze, sights, elevation and position.

It is apparent that although the methods to exploit these developments were evolving, they had not as a whole been driven into artillery doctrine from the top: their use at Cambrai was an innovation from below, for the idea of a surprise bombardment using the new methods came from Brigadier General Tudor, officer Commanding Royal Artillery of the 9th (Scottish) Division. By August he had discussed his idea with Brigadier General Hugo de Pree of IV Corps General Staff and in turn had gained the approval of the commander of IV Corps, Lieutenant General Sir Charles Woollcombe. That the new methods had not been enthusiastically adopted may have been due to lingering doubts about their effectiveness: IV Corps Order 320, issued on 15 November 1917, said that the barrage “_being unregistered cannot be expected to be as accurate as usual_”.

The surprise bombardment using predicted firing from there on became a key part of Third Army’s plan. The concealment of assembly of more than 1000 guns and howitzers on the fronts of III and IV Corps and the success of the opening bombardment at 6.10am on 20 November 1917 were strong contributory factors to the bells ringing in Britain three days later. It was not just surprise that made the artillery effective: weight of firepower and the proportion devoted to neutralisation of enemy batteries were also important factors. The number of guns and the 900,000 rounds assembled for the operation were approximately equivalent to those used in the preliminary bombardment to the successful attack on Vimy Ridge six months before.

Dawning of a new era: tanks

If the secret concentration of a large number of guns was impressive, the assembly of 476 tanks possibly surpassed it, although when running in low gear at low engine speed, the new Mark IV version tanks, although just as heavy, slow and difficult to manoeuvre as their predecessors, were remarkably quiet. Even so, aircraft flew up and down the area on 18 and 19 November as a ruse to mask the sound as the tanks moved up. While this and other signs of unusual activity had somewhat raised the state of alert – for example, German Second Army placed_54 Division_ at readiness – and raids had taken prisoners from the assault units, it is clear from German reports that their intelligence had failed to identify the imminence and nature of the British attack. The planned role for the tanks was to advance en masse, with the objective of crushing wire defences and suppressing firing from trenches and strong points. The innovation of fascines to be dropped as makeshift bridges enabling the crossing of a wide trench removed one of the known shortcomings of the current tank design. Much attention had been paid to training, particularly for co-operation between infantry and tank, with the units designated to make the initial assault being withdrawn to Wailly for this purpose. An innovation was that the infantry would follow the tanks through the gaps they made, moving in “worms” rather than the familiar lines: their training seems to have done much to improve infantry confidence in the tanks, hitherto seen as a mixed blessing. The tanks were a notable operational success. Shrouded by mist and smoke, they broke into the Hindenburg Line defences with comparative ease in many places.

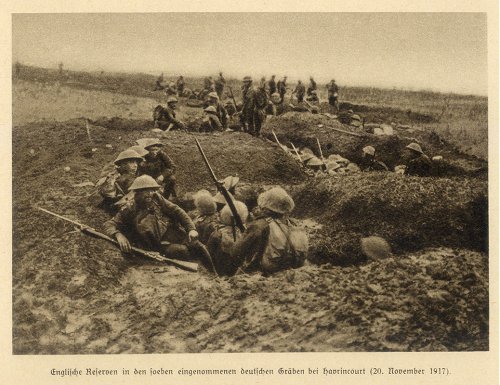

Havrincourt British infantry, having moved up into captured German trenches at Havrincourt on 20 November 1917.

British infantry, having moved up into captured German trenches at Havrincourt on 20 November 1917.

Phase: the Tank attack, 20 – 21 November 1917

Third Army (Byng)

Cavalry Corps (Kavanagh)

1st Cavalry Division

2nd Cavalry Division

5th Cavalry Division.

III Corps (Pulteney)

6th Division

12th (Eastern) Division

20th (Light) Division

29th Division.

IV Corps (Woollcombe)

36th (Ulster) Division

40th Division

51st (Highland) Division

56th (1st London) Division

62nd (2nd West Riding) Division.

VII Corps (Snow)

55th (West Lancashire) Division.

The battle

The attack was launched at 6.20am on the 20th November. The British Divisions in the front line were, from right to left, the 12th (Eastern), 20th (Light), 6th, 51st (Highland), 62nd (West Riding) and 36th (Ulster). In immediate support was the 29th, and ready to exploit the anticipated breakthrough and sweep round Cambrai were the 1st, 2nd and 5th Cavalry Divisions.

The Tank Corps deployed its entire strength of 476 machines, of which more than 350 were armed fighting tanks. They were led by the Tank Corps GOC, Hugh Elles, in a Mk IV tank called ‘Hilda’.

The attack opened with an intensive predicted-fire barrage on the Hindenburg Line and key points to the rear, which caught the Germans by surprise. Initially, this was followed by the curtain of a creeping barrage behind which the tanks and infantry followed.

On the right, the 12th (Eastern) Division moved forward through Bonavis and Lateau Wood, and dug in a defensive flank to allow the cavalry to pass unrestricted, as ordered. On the extreme right of the attack, the 7th Royal Sussex got into Banteux, which had been subjected to gas attack from Livens projectors.

The 20th (Light) Division captured La Vacquerie after a hard fight and then advanced as far as Les Rues Vertes and Masnieres where there was a bridge crossing the St Quentin Canal. Securing the bridge was going to be vital for the 2nd Cavalry Division, planning to move up to the east of Cambrai. However, the weight of the first tank to cross the bridge, ‘Flying Fox’, broke its back. Infantry could cross slowly by a lock gate a couple of hundred yards away, but the intended cavalry advance was effectively halted. An improvised crossing also allowed the B squadron of the Fort Garry Horse to cross, but they were left unsupported and withdrew. For no good reason, it was not noticed that further canal crossings at Crevecoeur-sur-Escaut were very lightly defended, until too late in the day.

The cavalry were hampered by uncertain communications regarding progress and the collapse of the canal bridge at Masnieres under weight of a passing tank did not help, either, as there were few crossing points. But it seems that the cavalry was indifferently commanded. Lieutenant General Sir Aylmer Haldane (VI Corps) assigns blame to Cavalry Corps commander, Lieutenant General Charles Kavanagh, “who was vague as regards his intentions”.

The 6th Division, once it had crossed the Hindenburg Line, moved forward and captured Ribecourt and fought as far as and through Marcoing. The 5th Cavalry Division advanced through them but were repulsed in front of Noyelles.

The 51st (Highland) Division had a very hard fight for Flesquieres, but its failure to capture it and keep up with the pace of the advance on either side left a dangerous salient which exposed the flanks of the neighbouring Divisions. Much has been written about the failure of the Division to move on Flesquieres and the apparent unwillingness of its commander, Major General George Harper, to support the idea of a tank attack and the new infantry tactics to go with it. This has its roots in criticism by Baker-Carr and Liddell Hart in 1930 (eight years after Harper’s death), comprehensively demolished by John Hussey in his article ‘Uncle Harper at Cambrai’, Stand To! The journal of the Western Front Association, 62 (2001), pp.13-23, reprinting from British Army Review, 117 (1997).

On the left of Flesquieres, the 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division fought hard through the ruins of Havrincourt, up to and through Graincourt and by nightfall were within sight of Anneux in the lee of the commanding height crowned by Bourlon Wood. The division had covered almost five miles from their start point, and were exhausted. (This was later claimed to be a record advance in the Great War for troops in battle).

The 36th (Ulster) Division moved up the dry excavations of the Canal du Nord, and lay alongside the Bapaume-Cambrai road by nightfall. By recent Western Front standards, the advance was little short of miraculous, and victory bells were pealed in Britain on the 23rd. In the light of subsequent events, this was indeed ironic.

Successful though the day was, with an advance three to four miles deep into a strong system of defence in little over four hours at a cost of just over 4000 casualties, it was on 20 November that things began to go wrong, leading inexorably to failure ten days later. Third Army failed to fulfil its objectives, notably in that the cavalry had been unable to push through a gap at Marcoing-Masnieres and on to encircle Cambrai itself. Nowhere had the Masnieres-Beaurevoir line been convincingly penetrated, and the key Bourlon ridge, dominant of the northern half of the battlefield, remained firmly in German hands. No fewer than 179 tanks had been destroyed, disabled or broke down. By the afternoon, the attack had already lost its early impetus.

Seeds of future failure

Byng was all for carrying on, issuing orders to III Corps at 8pm to continue the push into the Masnieres-Beaurevoir line to allow passage of the cavalry, and to IV Corps for finally completing the capture of Flesquieres and Bourlon before the 48 hour limit was reached. With few fresh troops, surprise lost, the tanks weakened and the field artillery in the process of moving up, the renewed attack had all the hallmarks of “penny packet” Somme fighting and achieved little. Late on 21 November, Byng ordered the III Corps operation to halt and for consolidation to take place.

Driven by the tactical importance of the position, absence of signs of growth of German strength and the fact that Third Army had not yet called upon V Corps (which had been placed at its disposal as reserve at the outset of the battle), Haig ordered Byng to continue with the attack on Bourlon. This was a serious command failure. The audacious sweep to capture Cambrai and force evacuation of a wide area to the Scarpe had become a bitter yard by yard fight for a difficult feature of landscape.

Phase: the capture of Bourlon Wood, 23 – 28 November 1917

Note: the official title of this phase is a little misleading.Only IV Corps fought for the wood itself.

Third Army (Byng)

III Corps (Pulteney)

6th Division

12th (Eastern) Division

20th (Light) Division

29th Division.

IV Corps (Woollcombe)

1st Cavalry Division

2nd Cavalry Division

Guards Division

2nd Division

36th (Ulster) Division

40th Division

51st (Highland) Division

56th (1st London) Division (transferred to VI Corps on 24 November)

62nd (2nd West Riding) Division.

VII Corps (Snow)

55th (West Lancashire) Division.

The battle

When first presented with the Byng’s plan for the attack, Douglas Haig recommended strengthening the left flank in order to take Bourlon Wood very early. He wasted his breath: Byng ignored his advice. By nightfall on the 20th, it was clear that Haig had been right. From the dominating height of the wood, the Germans held the British advance in front of Anneux and Graincourt. There was good news, however, as the 51st (Highland) Division finally crept into Flesquieres, abandoned during the night by the Germans.

On the morning of the 21st, the Highlanders moved forward with the aid of two tanks towards Fontaine Notre Dame, but were held up by fire from the wood. Harper ordered a halt until the 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division had captured the heights. The latter had a violent and costly battle for Anneux, led by the 186th Brigade under Roland Boys Bradford. To the north, the 36th (Ulster) Division, planning to continue their advance beyond Moeuvres, waited for the success signal, signifying that the 62nd had captured Bourlon. It never came, for the 62nd could not penetrate beyond the sunken lane facing the wood. By the evening of the 21st, Haig was satisfied that ‘no possibility any longer existed of enveloping Cambrai from the south’. The British were now in an exposed position in the lee of Bourlon Wood, the capture of which would still prove to be useful, in cutting German access to key light railway lines feeding their front. Haig and Byng decided to press on, even though it meant deepening the salient that had been created and throwing in even more troops into this northern sector of the battlefield.

On 22 November, the GOC 40th Division at Beaumetz-les-Cambrai received orders to relieve the 62nd Division the next day. The 40th was a division of Bantams, men under regulation height. By now the roads were breaking up under the strain of thousands of men, wagons and lorries. It took 40th Divisional HQ 15 hours to travel the 9 miles to Havrincourt. A relief and assault plan was quickly drawn up: 121 Brigade to capture Bourlon, 119 Brigade to go for the wood, both jumping off from the sunken lane. On their right, the 51st would move forward to Fontaine. On the left, the 36th would go in again at Moeuvres. 92 tanks would support these units. They attacked through ground mist on the morning of the 23rd. Some of the units of the 40th had to cross 1000 yards down the long slope from Anneux, across the sunken lane and up the final rise into the wood, all the while under shell fire. There was close and vicious fighting in the wood, but after 3 hours the Welsh units of 119 Brigade were through and occupying the northern and eastern ridges at the edge of the undergrowth. 121 Brigade was cut down by heavy machine gun fire, and few men got as far as the village. 7 tanks did but were unsupported and the survivors withdrew. On the flanks, the 36th and 51st Divisions made little progress, against strengthening opposition.

Over the next few days, further troops were thrown into the battle, including the Guards Division, which advanced into Fontaine. Once his troops had been driven from the wood, the enemy switched all of his artillery onto it. Battalions in the wood were wiped out. Three companies of the 14th HLI miraculously penetrated to the far side of Bourlon but were cut off and gradually annihilated. And it began to snow. The weary troops settled into the newly-won positions. The British now sat some way ahead of the position of 20th November, being in possession of a salient reaching towards Cambrai, with the left flank facing Bourlon and the right alongside the top of the slope which ran down towards Banteux.

Seeds of future failure

“All arms” fighting broke down, the tanks few and impotent in the thick woodland of Bourlon and La Folie, and defeated in the ruined streets of Fontaine Notre Dame. Behind the front, the roads resembled those at Morval a year before, the traffic unable to move through mud and snow, along roads for which there was insufficient stone and labour to carry out adequate running repairs. The “ray of hope” had become a slow, piecemeal and inevitably costly shambles. Third Army closed down offensive operations on 27 November and units were ordered to consolidate. Three days later, The German Army struck back.

Note: VI Corps (Haldane) carried out a major subsidiary action at Bullecourt on 20 November 1917, using 3rd and 16th (Irish) Divisions.

Phase: the German counter attack, 30 November – 3 December 1917

Third Army (Byng)

III Corps (Pulteney)

1st Cavalry Division

2nd Cavalry Division

4th Cavalry Division

5th Cavalry Division

Guards Division

6th Division

12th (Eastern) Division

20th (Light) Division

29th Division

36th (Ulster) Division

61st (2nd South Midland) Division.

IV Corps (Woollcombe) (relieved by V Corps on 1 December)

2nd Division

47th (2nd London) Division

59th (2nd North Midland) Division.

V Corps (Fanshawe)

2nd Division

47th (2nd London) Division

51st (Highland) Division (entered into Corps command 3 December)

VI Corps (Haldane)

3rd Division

56th (1st London) Division (relieved by 51st (Highland) Division on 2/3 December).

VII Corps (Snow)

21st Division

55th (West Lancashire) Division.

Fontaine-Notre-Dame A British tank, damaged and captured in Fontaine Notre Dame, in a photograph taken once the Germans had defeated the Guards Division attack through the village.

A British tank, damaged and captured in Fontaine Notre Dame, in a photograph taken once the Germans had defeated the Guards Division attack through the village.

The German reaction to the initial British attack

On 17 December, Lieutenant General Thomas Snow wrote from VII Corps HQ to Third Army: _“The abnormal movement and increased registration were duly recorded in the Corps Daily Intelligence Summary; these were believed at first to be connected with an expected divisional relief, though as time went on the suspicion grew that they might mean something more_“.

VII Corps stood to the right of the tired III Corps. Facing the area Gouzeaucourt-Epehy, it had not been part of the main attacking force at Cambrai but had carried out subsidiary operations. The “something more” reported to Snow over the days since the British attack had been called off had since turned into disaster for both Corps. Recovering from the initial shock of the attack, Second Army had quickly arranged for reinforcements to move to Cambrai. By good fortune, 107 Division had arrived in the area to relieve a Landwehr Division on 9 November undetected by British intelligence – and was deployed piecemeal to help stem the attack next day. The situation for the Germans was serious for a while: two divisions virtually destroyed, gaps in the line, ammunition short, and infantry details being sent in to shore up the defences. The fighting at Bourlon was bitter and at times worrying, with reports of men retiring in disorder from Fontaine. But if the slowdown in the British attack in the afternoon of 20 November had given precious time to regroup, the concentration on Bourlon after 21 November provided the opportunity to thoroughly reinforce. An entirely new command, the XXIII Reserve Corps or Busigny Group, came into being on 23 November, bringing together the 5 Guard, 30, 34 and 220 Divisions, arriving from other parts of the front to face the British VII Corps. It is little wonder that Snow received reports of unusual activity. Other formations arrived to reinforce the Caudry and Moser Groups, opposing III and IV Corps. By 27 November, the balance had swung to such an extent that an opportunity for a vigorous counter attack presented itself.

Counter strike On the same day that Byng was closing down his offensive, Second Army received orders to hit back. The plan – devised and organised with exceptional pace for an action of this magnitude – was for a main force from the Busigny and Caudry Groups to strike from the south, recapture the Hindenburg positions at Havrincourt and Flesquieres and then roll up the British forces now stuck in Bourlon Wood, when forces of the Arras Group north and west of that area would also join the attack. Such was German confidence that reserves were assembled to exploit success, and a further operation north of Saint Quentin was authorised to add to the pressure. On 28 November, operations opened with a heavy gas bombardment of Bourlon.

Two days later, the counter attack began in earnest. On the right flank, south of the Gouzeaucourt-Bonavis road, the break into British positions was swift. The defending 55 (2/West Lancashire) Division and much of 12 (Eastern) and 20 (Light) Divisions seemed to evaporate, and Snow called for reinforcements as early as 9am. Many artillery batteries soon came within range of advancing German infantry. Both they and units hurriedly ordered to shore up the clearly splintering defence were shocked at what they saw. Not least of them was the Guards Division, still recuperating from a mauling in Fontaine Notre Dame and now heading into what would become a bitter fight to hold the enemy at Gouzeaucourt: “First we had to struggle through the flood of terrified men … nothing seemed to stem the torrent of frightened men with eyes of hunted deer, without rifles or equipment, among them half-dressed officers presumably surprised in their sleep, and gunners who had had the sense and calmness to remove the breech blocks from their guns and were carrying them in their hands. Many were shouting alarming rumours, others yelling “Which is the nearest way to the coast?”

[Norman D. Cliff, To hell and back with the Guards (Braunton, Devon: Merlin Books Limited, 1988) p.85]

Counter strike The German counter attack pushed the British forces back through Gonnelieu and Villers Guislain.

The German counter attack pushed the British forces back through Gonnelieu and Villers Guislain.

The German plan was simply to cut of the neck of the salient by attacking on each side, with the strongest blow to come on the southern side. The blow fell at 7.30am on the 30th November, and was devastatingly fast and effective. By 9am, the Germans had penetrated almost 3 miles towards Havrincourt Wood. Byng’s Third Army faced disaster, with the real prospect of several divisions being cut off in the trap. The first attack fell on the 55th (West Lancashire) and 12th (Eastern) Division on the south-eastern side of the salient. The Germans climbed the slope to re-take Lateau Wood, pushed up the complex of shallow ravines south of Banteux, moved through Villers Guislain and past Gouzeaucourt. Amongst the troops defending the artillery positions at Gouzeaucourt were the_11th United States Engineer Company_. The direction of the assault was across British divisional boundaries, and the command structure rapidly broke down as the troops became mixed up.

Three German divisions attacked to the north, supported by an intense Phosgene barrage, intending to cut the Bapaume-Cambrai road near Anneux Chapel. They were repulsed by the machine gun barrage of the 47th (London), 2nd and 56th (London) Divisions, who had relieved the 36th and 40th. No Germans reached the road. Fierce fighting continued in the southern area for Gonnelieu, Les Rues Vertes and Masnieres.

Eventually, on the 3rd December, Haig ordered a retirement ‘with the least possible delay from the Bourlon Hill-Marcoing salient to a more retired and shorter line’. The audacious plan had failed and although some ground had been gained, in places the Germans were now on ground formerly occupied by the British. A small salient remained at Flesquieres, which was an exposed position ruthlessly exploited by the German assault in March 1918.

The improvised defence gradually sealed the position and once again an initially promising attack lost momentum. The German attack met a far stronger defence north of the road, but even there, weight of artillery and numbers told, and hard-won positions were reluctantly given up by the British. Once again, the battle resembled the Somme: piecemeal attack and improvised counter attack. The German army suffered from problems familiar to the BEF: heavy losses, chaotic supply, and battlefield command breakdown that did not seize upon and propagate success. By 5 December, the line had re-stabilised. The net result of the Cambrai operation in terms of ground was that north of Gonnelieu the British had gained from their 20 November start line, standing on the Hindenburg Support positions snaking around Flesquieres and Welsh Ridge – while south from Gonnelieu they had been pushed back an average of 3000 yards with the loss of Villers Guislain. Both sides now occupied their respective bulges in an S-shaped double salient.

Enquiry and recriminations

Viewed as a heavy hit and run raid, Cambrai had been a failure. As a more strategic operation, designed to punch a deep hole, capture Cambrai, disrupt German rail communications and compel withdrawal from there to the Scarpe, it was a dismal defeat. Stories began to filter back of headlong retreat; of Generals caught in their pyjamas, and of new, wonder German tactics that sliced easily through the British defences. Questions were rightly asked in the War Cabinet, which requested an enquiry. Haig pre-empted it, having already organised one of his own.

The collective view of the operational factors contributing to British defeat was outlined very clearly in the papers assembled for the enquiry. That the enemy attack had been a surprise was denied. All those consulted said it was expected and suitable defensive measures had been taken. Far from admitting that the men holding these positions were tired, having not been relieved, on the contrary they were, according to Byng, “elated, full of fight”. Both of these points are open to challenge. Byng, Haig and Smuts all assigned the absence of serious resistance on the southern part of the front to a lack of training among junior officers, NCOs and men – a much more credible factor, but one directly attributable to the rush to undertake the operation despite advice from the staff that the divisions were simply not in a condition to undertake it. The tactically poor position and thinly held front resulting from the 20 November assault is hardly mentioned and where it is, is denied. Reports also mention the panic-inducing effect of rumours of defeat passing quickly between units and back down the lines of communication. No mention is made of the breakdown of all arms fighting, nor the serious communication failures that led to the commander of 29th Division (Major General Sir Henry de Beauvoir de Lisle) claiming that he knew nothing of the German attack before it was upon his headquarters.

The fact remains that, innovative as it was, the British assault was insufficiently successful. The initially winning operational factors proved unequal to the task of stopping the enemy from regrouping. In addition, German tactics had proven an ability to break quickly into a sketchily held front: a portent for 1918.The “dawn of hope” theory of Cambrai has merit, but as far as evidencing a learning curve is concerned, it is overstated. All arms success had come by luck rather than great design. More important is that the battle provided a basis from which operational strengths could be identified and refined, and weaknesses eliminated, by the time of the key victories at Hamel and Amiens in June and August 1918.

Enquiry at Hesdin The papers of the enquiry into the defensive failure at Cambrai are held at the National Archives in Kew.

The papers of the enquiry into the defensive failure at Cambrai are held at the National Archives in Kew.

Casualties

Third Army reported losses of dead, wounded and missing of 44,207 between 20 November and 8 December. Of these, some 6,000 were taken prisoner in the enemy counterstroke on 30 November. Enemy casualties are estimated by the British Official History at approximately 45,000.

| Senior Officer casualties | 20 November 1917 – 7 December 1917 |

|---|---|

| Lt-Col William Alderman DSO | Officer commanding 6th Royal West Kents. Killed in action 20 November 1917. Buried in Fifteen Ravine British Cemetery. |

| Lt-Col Thomas Best DSO and Bar | Officer commanding 1/2nd Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. Killed in action 20 November 1917. Buried in Ruyaulcourt Military Cemetery. |

| Lt-Col Charles Linton DSO MC | Officer commanding 4th Worcesters. Killed in action 20 November 1917. Buried in Fins New British Cemetery. |

| Lt-Col William Kennedy MC | Officer commanding 18th Welsh Regiment. Killed in action 23 November 1917. Commemorated on Louverval Memorial to the Missing. |

| Lt-Col Clinton Battye DSO | Officer commanding 14th Highland Light Infantry. Killed in action 24 November 1917. Buried in Moeuvres Communal Cemetery Extension. |

| Brigadier-General Roland Boys Bradford VC | Officer commanding 186 Brigade HQ. Aged 25 when killed on 30 November 1917. Buried in Hermies British Cemetery. |

| Lt-Col Kenneth Field DSO | Officer commanding 38th Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery. Killed in action 30 November 1917. Commemorated on Louverval Memorial to the Missing. |

| Lt-Col Henry Gielgud MC | Officer commanding 7th Norfolk Regiment. Killed in action 30 November 1917. Commemorated on Louverval Memorial to the Missing. |

| Lt-Col Ralph Hindle DSO | Officer commanding 4th Loyal North Lancashire Regiment. Killed in action 30 November 1917. Buried in Unicorn Cemetery, Vendhuile. |

| Lt-Col Donald Anderson MC | Machine Gun Officer, 61st Division. Killed in action 3 December 1917. Commemorated on Louverval Memorial to the Missing. |

Subsequent: the action of Welsh Ridge, 30 December 1917

Third Army (Byng)

V Corps (Fanshawe)

63rd (Royal Naval) Division.

VII Corps (Snow)

9th (Scottish) Division.

On 30/31 December, German troops dressed in white camouflage suits surprised British battalions in snow on the southern part of the Cambrai front. A difficult defensive action took place: the Action of Welch Ridge.