Two years after U.S. withdrawal, the Taliban enjoys an iron-fisted grip on Afghanistan (original) (raw)

Two years ago on this day, the Taliban marched into Kabul and triumphantly seized back control of Afghanistan. Two weeks later, on Aug. 30, 2021, the last U.S. soldier left the country. Since the U.S. withdrawal, the Taliban has consolidated its power, sheltered and supported numerous regional and global terror groups, crushed armed opposition and rival terror groups, and ruthlessly suppressed the rights of the Afghan people.

President Joe Biden announced on April 14, 2021 that all American soldiers would leave Afghanistan by Sept. 11, 2021, exactly 20 years after that Al Qaeda launched its terror attack on the U.S.

Biden, who as vice president wanted to leave Afghanistan in 2011 after the U.S. killed Osama bin Laden, justified his decision to leave the country by claiming that he was bound by the Doha Agreement, the so-called peace agreement between the U.S. and the Taliban that was negotiated and signed by the Trump administration on Feb. 29, 2020.

The Taliban, which before the signing of the Doha Agreement was slowly gaining control of rural districts throughout Afghanistan, used the time between the signing of the deal and Biden’s announcement to lay the groundwork for its final push to take control of Afghanistan. The Taliban softened the support of local Afghan leaders and military commanders by convincing them to surrender or flee once the inevitable announcement of the U.S. withdrawal was made. Those who resisted would be crushed, the Taliban warned.

The Taliban immediately implemented its plan to take control of Afghanistan. First it would expand its control of the rural districts, then it would seize provinces and march into Kabul. On April 13, 2021, the Taliban controlled 77 of Afghanistan’s 407 districts, and contested another 194, according to a long-term assessment by FDD’s Long War Journal.

Within three months, the Taliban controlled 221 districts and contested 113. On Aug. 6, 2021, Nimroz in southwestern Afghanistan was the first province to fall. Nearly all of Afghanistan’s remaining 33 provinces fell to the Taliban by the time it marched into Kabul nine days later. Panjshir province, the last remaining holdout, collapsed on Sept. 7, 2021.

The Biden administration, and senior U.S. military, intelligence, and State Department officials were stunned by the Taliban’s swift victory. At the time of the withdrawal’s announcement, the official assessments indicated that the Afghan government would have a two-year buffer before it would be threatened by the Taliban.

Since the withdrawal, many so-called Afghan experts predicted that the Taliban would swiftly fracture and turn on itself, or that moderates within the group would rise to prominence and usher in a kinder, gentler Taliban that would suddenly respect human rights, create an inclusive government and serve as a viable counterterrorism partner. Two years after the takeover of Afghanistan, nothing could be further from the truth.

Meet the new Taliban, same as the old Taliban: the Permanent Interim Government

On Sept. 8, 2021, the Taliban announced its so-called “interim government.” Western officials were hopeful that the Taliban would create an inclusive government that integrated leadership from outside of the Taliban’s command. The Taliban, which always maintained that its “Islamic Emirate has not readily embraced this death and destruction for the sake of some silly ministerial posts or a share of the power,” had other ideas.

The latest iteration of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan looks much like the previous iteration. Many of the new ministers served in the Taliban’s government from 1996 to 2001, before the U.S. ousted the group. The ‘new’ Taliban leaders were serving in the Taliban’s shadow government during its insurgency from 2002 until Aug. 2021.

Two of the top three leaders are Taliban royalty. Mullah Yacoub, the Taliban’s minister of defense, is the son of Mullah Omar, the group’s founder and first emir. Sirajuddin Haqqani, the minister of interior, is the son of famed Taliban leader Jalaluddin Haqqani. Both served as co-deputy emirs in the shadow government as well as today.

The Taliban’s government includes Specially Designated Global Terrorists, leaders sanctioned by the United Nations, and former detainees from Guantanamo Bay. Even Al Qaeda leaders hold offices in the Taliban’s government.

There has been very little turnover within the Taliban’s government since it was announced two years ago. The Taliban’s minister of state has been replaced, reportedly due to illness, and its first education minister was fired due to a policy disagreement.

Despite numerous predictions that influential Taliban factions would immediately turn on each other to grab power or due to policy disagreement, there has been zero evidence that this has happened. The Taliban leadership has remained united and followed the directives from its emir, Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada.

Crushing the opposition

Immediately after seizing power, the Taliban turned its sights on the last remaining holdouts from the Afghan government and military. Resistance to the Taliban coalesced in the central mountainous province of Panjshir, under the command of Ahmad Masoud, the son of famed anti-Taliban leader Ahmad Shah Massoud, and in southern Baghlan province under Amrullah Salah, the last vice president of Afghanistan.

The Taliban quickly organized thousands of fighters and assaulted the mountainous redoubts of the resistance. Salah and Massoud’s forces were swiftly routed and forced to go underground.

The resistance to the Taliban flared again in the spring and summer of 2022, but again the Taliban massed its forces and drove Massoud and Salah’s forces underground. Today, resistance activity is limited to low scale guerrilla operations that does not seriously threaten the Taliban’s grip on power. The Afghan resistance has an uphill battle, with little foreign support, limited access to weapons and funds, no territory under its control, and no foreign safe havens where it can organize and strike back.

The Islamic State Khoransan Province (ISKP), an avowed enemy of the Taliban, can launch the occasional terror attack or assassination within Afghanistan, but it does not pose a serious threat to the Taliban’s primacy. The Taliban holds all of the advantages.

The Taliban can muster hundreds of thousands of troops while ISKP has only several thousands of fighters. The Taliban controls all of the territory of Afghanistan while ISKP operates in the shadows. The Taliban possesses billions of dollars in weapons, ammunition, vehicles, bases and supplies left behind by the U.S., while ISKP is forces to scavenge for war material. The Taliban has the support of foreign states such as Pakistan, as well as a host of terror groups on its side, while ISKP remains isolated as it does not play well with others due to its demands that everyone swear allegiance to its self-styled caliph. The only field where ISKP can match the Taliban is ideological fervor.

The real threat posed by ISKP is its ability to poach the disaffected or more radical members of the Taliban and its allied terror group. As the Taliban established its control of Afghanistan, it has largely worked to keep a lid on regional terror groups in order to placate countries like China (the exception is the Movement of the Taliban in Pakistan, which is very active in Pakistan). ISKP makes the argument that the Taliban is beholden to foreign powers and it is not waging a pure form of jihad. The Taliban’s victory has largely tamped down this argument, but this could be a problem for the group over time.

Doubling down on support for Al Qaeda and its allies

A key component of the Doha Agree was that the Taliban would not allow foreign terror groups to use Afghan soil to launch attacks against the U.S. or its allies. The Taliban has made this promise in the past, even before 9/11, but never intended to follow through. The same is true today. Additionally, the Taliban has denied that foreign groups are even operating within Afghanistan.

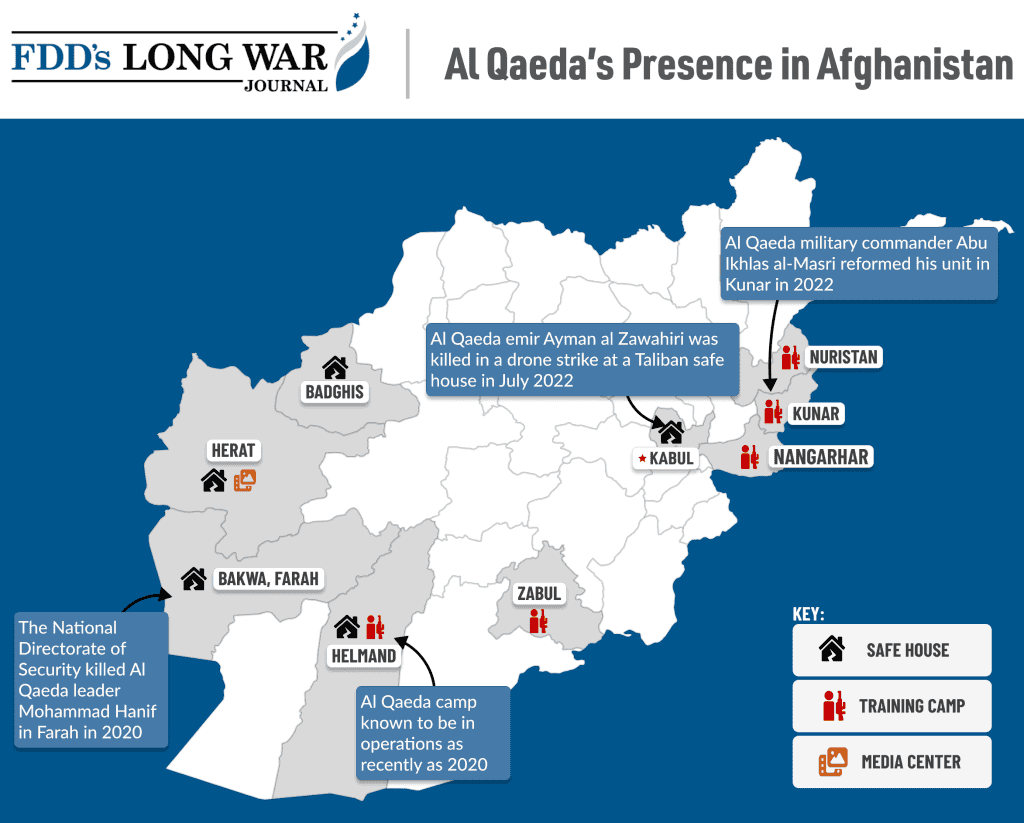

Since the U.S. withdrawal, the Taliban – Al Qaeda alliance has only strengthened. Al Qaeda was so confident in its relationship with the Taliban that its last leader, Ayman al Zawahiri, was living in a safe house in Kabul that was managed by a lieutenant of Taliban deputy emir and interior minister Sirajuddin Haqqani. The U.S. discovered Zawahiri’s presence and killed him in a drone strike on July 31, 2022.

Zawahiri’s presence in Kabul wasn’t the only piece of evidence that demonstrated the enduring ties between the Taliban and Al Qaeda. On June 9, the United Nations Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, issued a report that noted that Al Qaeda is operating training camps in six of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces, as well as safe houses and a media center.

Al Qaeda is also operating “suicide bomber training camps” for the Movement of the Taliban in Pakistan. Three dual hatted Al Qaeda and Taliban leaders are serving in the Taliban’s government, and the Taliban is issuing passports and national identification cards for Al Qaeda members and their families. The Taliban’s ministry of defense is using Al Qaeda training manuals.

The Taliban’s grip on Afghanistan remains strong. Any false hopes that the Taliban would evolve into a moderate and peaceful regime that respects the rights of its people while serving as an effective counterterrorism partner should have been dashed the moment it took power.

Bill Roggio is a Senior Fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and the Editor of FDD's Long War Journal.

Tags: Afghanistan, Al Qaeda, Movement of the Taliban in Pakistan, Taliban